Psychiatrists' Use of Shared Decision Making in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: Patient Characteristics and Decision Topics

Shared decision making between patients and doctors has increasingly been advocated for in the medical literature ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). Some authors argue that patients have the right to be involved in decisions concerning their health care, whereas others use a more utilitarian approach, stating that increased involvement of patients might lead to improved adherence and could thus improve outcomes ( 4 ). Whatever the rationale underlying shared decision making, it can be achieved only when both parties (patients and physicians) commit to sharing decisions.

For somatic medicine, there have been numerous studies assessing patients' participation preferences as well as physicians' preferences for various types of decision making. From the patients' side, a strong interest has been shown for participating in decisions but not for taking complete control over treatment decisions ( 5 , 6 ). Studies of physicians' preferences indicate that a majority of physicians prefer shared decision making, both in theory and in practice ( 4 , 7 , 8 ).

However, context as well as various characteristics of the physician and patient may influence the use of participatory decision-making styles. Thus, for example, older physicians were reported to be more likely to prefer paternalism ( 4 ), and shared decision making might be provided predominantly to patients who request participation or to those with a higher level of education ( 9 ).

In psychiatry there has been a similar shift toward patient participation in recent years, with numerous treatment guidelines recommending shared decision making for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia ( 10 , 11 ). There are also data showing that patients with schizophrenia have levels of interest in shared decision making that are similar to those of patients with various somatic diseases ( 6 , 12 ).

However, there is only a little information about the attitudes psychiatrists have toward shared decision making and how they tailor their participatory approaches to certain patients or decision topics.

Methods

We surveyed 352 psychiatrists attending the congress of the German Society of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Nervous Diseases (DGPPN) held in November 2007. This annual meeting has approximately 6,000 visitors and thematically covers all aspects of psychiatry. Among the attendees asked to participate, the response rate was approximately 80%.

The questionnaires included items on demographic characteristics of the psychiatrists (age, gender, length of experience in the psychiatric field, type of institution, and percentage of patients with schizophrenia treated in 2007), as well as questions on psychiatrists' perception of sharing decision making with patients with schizophrenia.

Psychiatrists were asked to indicate which of three styles of decision making she or he was applying most frequently with patients with schizophrenia. Following the concept of Charles and colleagues ( 1 ), these three styles were defined as a paternalistic approach, shared decision making, and informed choice, and they were described to the psychiatrists with the following texts:

"You inform your patients about the most important treatment options and then try to convince the patients to accept the treatment option that you consider to fit the patients' needs best" (paternalistic approach).

"You inform your patients about the pros and cons of the most important treatment options. Then you encourage the patients to develop preferences upon which you and your patient develop a joint decision" (shared decision making).

"You inform your patients about the pros and cons of the most important treatment options. You accept your patients' treatment preferences and strictly aim at implementing them" (informed choice).

Psychiatrists were then requested to answer additional questions regarding whether certain patient characteristics were likely to lead to shared decision making (questionnaire A) and questions on whether certain decision topics would be suitable for shared decision making (questionnaire B). Because we expected the answers to questionnaire B to be influenced by the answers to questionnaire A (and vice versa), we randomly assigned questionnaire A to half of the sample (N=181, 51%) and questionnaire B to the rest (N=171, 49%).

Patient characteristics

In questionnaire A, psychiatrists were presented with 19 patient characteristics (for example, poor compliance with treatment and well informed about treatment options) that according to literature ( 13 , 14 ) might influence the use of shared decision making. Psychiatrists were asked about how likely they would be to share decision making with a patient with schizophrenia who had these characteristics. Possible scores range from 1, "I would surely not use shared decision making," to 6, "I would surely use shared decision making." The list of characteristics was developed by three experienced clinicians and pretested with regard to wording and clinical relevance by ten psychiatrists.

Decision topics

In questionnaire B, psychiatrists were given 19 decision topics (for example, whether patients should share in the decision about whether antipsychotic treatment is initiated and whether the patient should participate in psychoeducation) that have been found to be most frequent in psychiatric practice ( 15 ). The questionnaire was also pretested by ten psychiatrists. Again, psychiatrists were asked to use the 6-point scale to rate how likely they would be to share decision making on these topics with a patient with schizophrenia.

Participating psychiatrists were surveyed anonymously. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Technische Universität München.

Statistical analyses

Principal-component analyses with the oblique Promax rotation were conducted for both questionnaires. Principal-component analyses were applied to confirm the assignment from the items to the scales, and Promax rotation was chosen because we expected correlated scales. Following the recommendations of O'Connor ( 16 ) and Beauducel ( 17 ), the minimum-average partial test was applied, leading to the acceptance of three components for questionnaire A and two components for questionnaire B. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficients were above .84 for both questionnaires, which can be regarded as good and indicate that the data are suitable for the analyses.

Missing values (less than 2% in both questionnaires) were estimated for all items with the estimation-maximization algorithm ( 18 ) from SPSS, version 16, before the principal-component analyses. This procedure provides maximum likelihood estimates of missing data. The estimation-maximization algorithm is the preferred method for estimating missing data among pairwise or listwise deletion of missing data.

The resulting factors were then combined into scales. The scales were built by adding the item scores for each factor. We used scales instead of factor scores because factor loadings were sample dependent. To test whether ratings were above or below the midpoint of the scale ("neutral"), all scale means were tested against the theoretical middle of the scale (3.5) with a one-sample t test. Thus ratings above 3.5 indicate that psychiatrists would rather use shared decision making, whereas ratings below 3.5 indicate reservations about shared decision making.

Results

A total of 352 psychiatrists participated in the study. There were 209 male psychiatrists (59%) and 143 female psychiatrists (41%), their mean±SD age was 46.6±8.5 years, and their mean working experience in psychiatry was 15.8±9.3 years. Thirty-nine psychiatrists (11%) were working in university hospitals, 227 (65%) were working in state hospitals, and 83 (24%) were working in private practice (three missing values). Psychiatrists reported that they treated a mean of 29.3%± 20.1% patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia during the year 2007.

A total of 151 psychiatrists (44%) reported that they most frequently applied a paternalistic decision-making style, 173 (51%) said that they most frequently applied shared decision making, and 18 (5%) said that they most frequently applied informed choice (ten missing values). There was no association between sociodemographic variables and preferred decision style.

Psychiatrists who received questionnaire A did not differ from those who responded to questionnaire B with respect to age, years in psychiatry, gender, proportion of patients with schizophrenia, or preferred decision style.

Patient characteristics related to shared decision making

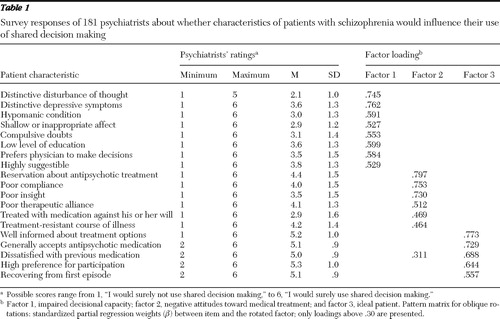

Table 1 presents the pattern of psychiatrists' (N=181) answers with respect to patient characteristics they considered relevant to applying shared decision making. Some characteristics were seen as speaking strongly in favor of shared decision making (for example, acceptance of medication, high preference for participation, and well informed), and other characteristics were seen as speaking clearly against the use of shared decision making (for example, disturbances of thought and shallow or inappropriate affect). As reported above, three factors were extracted from questionnaire A ( Table 1 ). The first factor represented 31% of the total variance. Correlations of the first factor with the second and third factors were .48 and .25, respectively. The second factor accounted for 11% of the total variance, and the correlation with the third factor, which accounted for 8% of the total variance, was .32.

|

Factor 1 (impaired decisional capacity) covered all items related to patients' psychopathology (for example, disturbance of thought, depression, and mania), as well as low levels of education, compulsive doubts, and a preference for the physicians to make the decisions. The mean score of the eight items loading high on factor 1 was 3.2±.8, slightly but significantly below the middle of the scale (t=-4.9, df=180, p<.001). Thus psychiatrists considered it unlikely that they would engage in shared decision making with patients showing any of these characteristics.

Factor 2 (negative attitudes toward treatment) covers items such as reservations about antipsychotic treatment, poor compliance, poor therapeutic alliance, and poor insight. Additional items related to involuntary treatment or treatment resistance. The mean scoring of the six items loading high on factor 2 was 3.9±1.0, slightly but significantly above 3.5 (t=4.8, df=180, p<.001). Thus psychiatrists indicated that they saw patients with these characteristics as probable partners in shared decision making.

Factor 3 (ideal patient) covered items characterizing patients as well informed about treatment options, generally accepting antipsychotic medication, dissatisfied with previous medication, having high preferences for participation, and recovering from a first episode of schizophrenia. The mean score for the items represented by factor 3 was 5.1±.7, significantly above the middle of the scale (t=32.6, df=180, p<.001), thus suggesting that patients with these characteristics would be involved with shared decision making.

Decision topics related to shared decision making

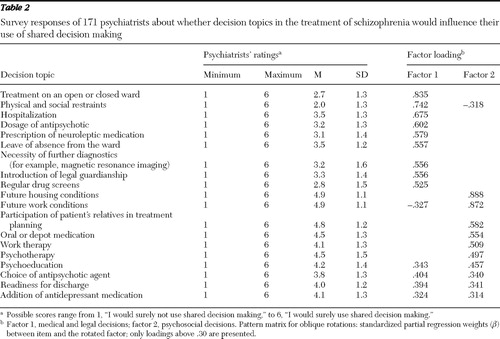

Table 2 presents the pattern of psychiatrists' (N=171) answers in questionnaire B with respect to decision topics. The first factor covered 31% of the total variance, and the correlation with the second factor, which covered 12% of the total variance, was .38.

|

Factor 1 (medical and legal decisions) covers items such as hospitalization, treatment in open or closed wards, prescription of antipsychotic drugs, diagnostic procedures, and drug screens. The mean score of the items loading high on factor 1 was 3.0±.9, significantly below the middle of the scale (t=-6.8, df=170, p<.001). The psychiatrists indicated that they would tend not to accept patient participation in these decision topics.

Factor 2 (psychosocial decisions) covers items related to decisions about psychosocial factors in treatment (work therapy, psychotherapy, and psychoeducation) and living conditions after acute treatment (future housing and work). Oral versus depot medication was the only item related to drug treatment loading on this factor. The mean score of the items loading high on factor 2 was 4.6±.8, significantly above the middle of the scale (t=16.8, df=170, p<.001). The score suggested that the psychiatrists considered these topics as being appropriate for shared decision making.

Three items loaded about equally high on both factors: which antipsychotic to choose, readiness for discharge, whether or not to use antidepressants.

Discussion

In this first large survey of psychiatrists' attitudes toward shared decision making, more than half reported regularly using a participatory style of decision making in schizophrenia treatment. Psychiatrists surveyed did not use a one-size-fits-all approach but clearly tailored their participatory approaches toward patients and decision topics that they believed to be suitable for shared decision making.

Approval of shared decision making in schizophrenia treatment

The approval of shared decision making in our sample can be seen as surprisingly high considering the strong tradition of paternalistic decision making in medicine and psychiatry ( 19 ), and it might reflect a change toward more participatory approaches in medical decision making. The generally high approval of shared decision making might also explain why psychiatrists' characteristics were not associated with whether they tended to approve of shared decision making, as has been shown in previous studies ( 9 ).

However, psychiatrists clearly tailored their participatory approaches to patients and decisions they believed to be suitable for shared decision making. Thus in our sample the use of shared decision making was judged appropriate for patients who exhibited insight, were well informed, or explicitly demanded participation. Additionally, psychiatrists saw shared decision making as a promising approach for patients who have exhibited poor compliance or have reservations about their current antipsychotic treatment. It is possible that a participatory approach with these patients is seen as an attempt to convince patients to accept antipsychotic medication.

Beyond certain patient characteristics, there are also decision topics that lend themselves to using a more participatory way of reaching decisions. Thus for decisions about psychosocial treatment, patient participation seems not only possible but rather necessary. Patients facing these decisions often have recovered from acute episodes, and these decisions inevitably require the positive commitment of the patient.

Despite this positive commitment to shared decision making, the survey suggested that there are quite a few obstacles to practicing shared decision making. In the case of impaired decisional capacity, psychiatrists had doubts about whether they can accept patients as competent partners in medical decisions. And for medical and legal decisions, psychiatrists had doubts about whether it is appropriate to share decisions about issues such as hospitalization, antipsychotic medication, or legal guardianship. These decisions may in many cases affect patients in acute episodes (for example, whether the patient would be treated in an open or closed ward), who at the time of the decision might have reduced decisional capacity. Furthermore, some of these decisions (for example, use of restraints) have to be made only after discussion and shared decision making have failed. Finally, decisions such as whether or not to treat with antipsychotics may, in the psychiatrists' view, have such an impact on the patient's life and the further course of illness that they fear negative consequences for the patient if they put these decisions up for discussion. Decisions concerning medical and legal issues were apparently seen mainly as the domain of an expert physician and not as a domain where both the patient and the physician decide together.

Only three medical decisions (choice of antipsychotic agent, readiness for discharge, and use of antidepressants as adjuncts) loaded on both factors, probably because they are both expert and psychosocial decisions. Thus choosing among different antipsychotics involves expert knowledge (the physicians' domain) as well as the knowledge of the person who must live with the drug and its side effects for several years.

Taking all results into account, psychiatrists reported the general desire to engage in shared decision making with most of their patients. However, they clearly looked at the individual patient and decision topic before deciding whether to share decisions. In this context, we believe that two issues deserve further discussion: the exclusion of patients with impaired decisional capacity from shared decision making and the lack of shared decision making in medical decisions.

Because shared decision making requires that patients are able to act as competent decision makers ( 2 ), it is appropriate that psychiatrists do not use shared decision making with everyone but first consider the patient's decisional capacity. Here our results support the findings of a qualitative study of psychiatrists in England, in which psychiatrists showed a strong preference for a cooperative therapeutic alliance with patients with schizophrenia, but they also considered patient competence as a critical obstacle to participatory approaches ( 13 ).

With regard to patients' decisional capacity, research on this issue in fact has shown that patients with schizophrenia often show poorer decisional capacity than persons without any physical or mental conditions (comparison group) ( 14 ). This poor performance of patients with schizophrenia, however, did not reflect an enduring inability. The performance of most patients with schizophrenia was equal to that of persons in the comparison group when they received an additional (educational) intervention that allowed them to review and reflect on the information necessary to consent to treatment ( 14 ).

In addition, a trial of the feasibility of shared decision making with acutely ill patients with schizophrenia revealed that although psychiatrists were often in doubt about their patients' decisional capacity ( 20 ), shared decision making was highly appreciated by both patients and psychiatrists and showed the potential to improve long-term outcomes ( 20 , 21 ).

Thus the obstacles to shared decision making reported in our survey might not be unchangeable (which stigmatizes patients), but our findings should prompt additional interventions that help patients become more capable of sharing decisions. Here, the use of psychoeducation, decision aids ( 22 ), and communication skills programs ( 23 ) and individual preparation of patients for decisions ( 24 ) might allow reasonable engagement of many patients in medical decisions, when they otherwise would have been judged as not being able to share in decision making.

With regard to the lack of shared decision making relating to medical decisions (for example, hospitalization and drug dosage), psychiatrists should keep in mind the potential negative consequences of not engaging patients in these decisions. Most of the disagreement between psychiatrists and patients occurs in these decisions. Many patients indicate that they would make these decisions differently when deciding alone ( 15 ). In addition, negative experiences (for example, not being given the option to make decisions) in acute episodes often predict patients' attitudes toward treatment for a long time afterward ( 25 ). Thus decisions made without patient participation (in a paternalistic manner) are at high risk of being reversed once the acute episode is over, which may have a negative influence on the long-term course of the illness.

Limitations

It is a limitation of our approach that we relied on psychiatrists' self-reports, because self-report about the use of shared decision making may reflect preferences rather than actual behavior, which is often determined by barriers such as time constraints rather than by any preferences for a participatory decision style ( 7 ). Hence self-reports often indicate higher rates of shared decision making ( 4 ) than observational studies show ( 26 ). Accordingly, the approval for shared decision making in schizophrenia treatment might be lower in clinical practice, and social desirability might have prevented some doctors from expressing even more explicit reservations about shared decision making.

In addition, in clinical practice psychiatrists do not respond to isolated characteristics when deciding about shared decision making, as they did in our survey, but rather they are confronted with a more complex situation (for example, a patient with reduced decision capacity facing a psychosocial decision).

Conclusions

A more thorough implementation of shared decision making in psychiatric practice might reduce psychiatrists' reservations about sharing decisions with more acutely ill patients. Interventions to improve patients' decisional capacity will play a key role in this implementation process.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Hamann has received honoraria or research supports from Janssen-Cilag, Eli Lilly and Company, Astra Zeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Heres has received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag, Sanofi-Aventis, Pharmastar, and Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Heres has accepted travel or hospitality payment from Janssen-Cilag, Sanofi-Aventis, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Kissling has received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag, Sanofi-Aventis, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T: Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science and Medicine 44:681–692, 1997Google Scholar

2. Hamann J, Leucht S, Kissling W: Shared decision making in psychiatry. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 107:403–409, 2003Google Scholar

3. Adams JR, Drake RE: Shared decision-making and evidence-based practice. Community Mental Health Journal 42:87–105, 2006Google Scholar

4. Murray E, Pollack L, White M, et al: Clinical decision-making: physicians' preferences and experiences. BMC Family Practice 8:10, 2007Google Scholar

5. Benbassat J, Pilpel D, Tidhar M: Patients' preferences for participation in clinical decision making: a review of published surveys. Behavioral Medicine 24:81–88, 1998Google Scholar

6. Hamann J, Neuner B, Kasper J, et al: Participation preferences of patients with acute and chronic conditions. Health Expectations 10:358–363, 2007Google Scholar

7. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T: Self-reported use of shared decision-making among breast cancer specialists and perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing this approach. Health Expectations 7:338–348, 2004Google Scholar

8. Shepherd HL, Tattersall MH, Butow PN: The context influences doctors' support of shared decision-making in cancer care. British Journal of Cancer 97:6–13, 2007Google Scholar

9. Guerra CE, Jacobs SE, Holmes JH, et al: Are physicians discussing prostate cancer screening with their patients and why or why not? A pilot study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22:901–907, 2007Google Scholar

10. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (ed): Treatment Guideline Schizophrenia [in German]. Darmstadt, Germany, Steinkopff Verlag, 2006Google Scholar

11. Guidance on the Use of Newer (Atypical) Antipsychotic Drugs for the Treatment of Schizophrenia. London, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002Google Scholar

12. Adams JR, Drake RE, Wolford GL: Shared decision-making preferences of people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 58:1219–1221, 2007Google Scholar

13. Seale C, Chaplin R, Lelliott P, et al: Sharing decisions in consultations involving anti-psychotic medication: a qualitative study of psychiatrists' experiences. Social Science and Medicine 62:2861–2873, 2006Google Scholar

14. Carpenter WT, Gold JM, Lahti AC, et al: Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:533–538, 2000Google Scholar

15. Hamann J, Mendel RT, Fink B, et al: Patients' and psychiatrists' perceptions of clinical decisions during schizophrenia treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196:329–333, 2008Google Scholar

16. O'Connor BP: SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer's MAP test. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers 32:396–402, 2000Google Scholar

17. Beauducel A: Problems with parallel analysis in data sets with oblique simple structure. Methods of Psychological Research 6:141–157, 2001Google Scholar

18. Little RJA: A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83:1198–1202, 1988Google Scholar

19. Parson T: The Social System. Glencoe, Ill, Free Press, 1951Google Scholar

20. Hamann J, Langer B, Winkler V, et al: Shared decision making for in-patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 114:265–273, 2006Google Scholar

21. Hamann J, Cohen R, Leucht S, et al: Shared decision making and long-term outcome in schizophrenia treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68:992–997, 2007Google Scholar

22. O'Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, et al: Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. British Medical Journal 319:731–734, 1999Google Scholar

23. Dow MG, Verdi MB, Sacco WP: Training psychiatric patients to discuss medication issues: effects on patient communication and knowledge of medications. Behavior Modification 15:3–21, 1991Google Scholar

24. Deegan PE, Rapp C, Holter M, et al: A program to support shared decision making in an outpatient psychiatric medication clinic. Psychiatric Services 59:603–605, 2008Google Scholar

25. Day JC, Bentall RP, Roberts C, et al: Attitudes toward antipsychotic medication: the impact of clinical variables and relationships with health professionals. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:717–724, 2005Google Scholar

26. Braddock CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, et al: Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA 282:2313–2320, 1999Google Scholar