Scope of Agency Control: Assertive Community Treatment Teams' Supervision of Consumers

Given the aim of enhancing self-direction of adults with severe mental illness, it is imperative that we better understand supervisory practices commonly used in community mental health that may undermine this essential component of the recovery process ( 1 ). We use the term agency control to refer to practices in which the treatment team maintains supervisory responsibility over consumers—for example, leasing agency-owned residences and serving as the consumer's representative payee. We theorize that agency control is a necessary condition for the employment of restrictive practices, which are freedom-limiting interventions—for example, making housing conditional on treatment adherence and making access to money contingent upon certain behaviors. The clinical rationale typically given for these practices is to increase treatment adherence and decrease maladaptive behaviors ( 2 ); the underlying assumption is that if these coercive practices are not used, consumers will not act in their own best interests. Other researchers have defined and studied related concepts, such as coercion ( 3 , 4 ), leverage ( 5 ), program intrusiveness ( 6 ), pressure or force ( 7 ), and therapeutic limit setting ( 8 ).

Community mental health teams may assume control over the consumers in their caseload in a variety of ways. The first, and most controversial, form of agency control is involuntary outpatient commitment. Treatment teams can threaten hospitalization if the committed consumer does not adhere to treatment. Second, teams designated as the consumer's representative payee, where the team receives and manages the consumer's disability funds, can potentially make access to funds contingent on adherence to treatment or decreasing maladaptive behaviors ( 2 , 9 ). Third, affordable and safe housing is a scarce resource for many consumers, and agencies may elect to own or lease housing while incorporating conditions of treatment adherence into the consumer's lease ( 10 , 11 ). Fourth, teams can use intensive medication monitoring techniques employing interpersonal pressures to ensure treatment adherence ( 12 , 13 ). For instance, it is not uncommon for practitioners to wait to observe a consumer swallow psychotropic medications before leaving the consumer's residence. Depot injections of antipsychotic medication, often used with resistant and nonadherent consumers, virtually eliminate choice for two to four weeks ( 14 ).

Whereas consumers' perceptions about these forms of control have been examined extensively ( 3 , 4 , 15 , 16 ), it is also important to gain a deeper understanding of the rate and occurrence of these coercive practices ( 17 ). To do this, studies have examined practitioners' use ( 8 , 12 , 18 ) or consumers' lifetime experience of coercive practices ( 5 ) and found that a range of practices are used in community mental health, with less restrictive practices used more often. One study also found significant regional variation in the use of restrictive practices ( 5 ), consistent with a large body of literature documenting such variation in the delivery of health care ( 19 ). In psychiatry, practice variations appear to be influenced by psychiatrist training and preferences ( 10 ). Variability of coercive practices across community mental health teams has not previously been reported in the literature. One model in particular—assertive community treatment—has been criticized as being particularly coercive ( 20 , 21 ), even though there is little empirical evidence that this is the case.

Assertive community treatment ( 22 ) is a program model that seemingly has a heightened potential for coercion given the key characteristics of both the model and the targeted consumer population ( 2 ). The intended clinical population includes individuals who have poor outcomes (for example, high rates of hospitalization or homelessness) in less intensive programs, sometimes because of difficulties in remaining engaged in treatment. Key model features include a multidisciplinary team that provides time-unlimited treatment, mostly in the community, using assertive engagement mechanisms and a high frequency of contacts ( 23 , 24 ).

Despite sharp criticisms by consumer advocates, little research substantiates claims that assertive community treatment is inherently coercive or, conversely, that assertive community treatment and the recovery model are compatible ( 25 ). In a focus group study Appelbaum and Le Melle ( 26 ) asked consumers and providers in assertive community treatment about their experiences in receiving and delivering various forms of leverage. The authors found little evidence that respondents perceived the model as coercive, although respondents did provide anecdotes indicative of coercion, such as timing the disbursement of funds after medication administration. Similarly, although consumers typically report high levels of satisfaction with assertive community treatment services ( 6 , 27 , 28 ), the areas where they report dissatisfaction tend to reflect coercion—for example, overemphasis on medications, lack of influence over treatment decisions, and general intrusiveness.

Little is known about factors influencing the exercise of agency control, notably whether it is primarily affected by consumer characteristics or by program or practitioner attributes. Some evidence suggests a direct relationship between consumer characteristics and the use of restrictive practices, such as more severe and chronic psychopathology ( 5 , 8 ), frequent hospitalizations ( 5 ), and arrest history ( 8 ).

If the assertive community treatment model is indeed inherently coercive and paternalistic ( 20 , 21 ), then we would predict that adopting the model with higher fidelity would be associated with greater agency control. However, we hypothesized that the key model features that distinguish assertive community treatment from other practices and are the focus of fidelity assessment ( 29 ) are not associated with agency control. Instead, we hypothesized that the quality of clinical practices germane to most treatment models, such as timely comprehensive assessments and person-centered treatment planning, may be more closely associated with less agency control. These practices, when done well, attend to consumer goals and choice ( 30 ), which would theoretically reduce indiscriminate and widespread use of agency control.

The delivery of high-quality, individualized mental health services partially depends on practitioner competencies ( 31 ). Studies comparing case managers with and without at least a master's level education found that those with more advanced training spent more time providing therapy and less time providing more typical case management duties—for example, money management and medication monitoring ( 32 , 33 ). Practitioners' pessimistic attitudes are also assumed to influence the degree to which restrictive practices are used, because those who are skeptical of the consumer's potential for achieving treatment successes will likely not encourage independence.

The study presented here assessed the prevalence of agency control across assertive community treatment teams in one state, thereby documenting team-level variation and providing benchmarks. Possible program, practitioner, and consumer correlates of agency control were also examined. We hypothesized that agency control would be positively associated with pessimistic attitudes, lower educational levels of practitioners, and more clinically challenging caseloads. We also hypothesized that poor basic clinical practices would be associated with greater agency control, while fidelity to the assertive community treatment model would be unrelated to agency control.

Methods

Study sites

Since 2001 Indiana's state mental health authority has promoted implementation of assertive community treatment teams throughout its public mental health system ( 34 , 35 ). In 2005 we contacted community support program directors in all 30 of the state's community mental health agencies, inviting each to enlist one treatment team at their center to participate in the study. To be eligible, a team must have provided assertive community treatment for at least six months; 24 (80%) of the agencies met these criteria. A few agencies had multiple teams that qualified; in these cases, the team that had been established for the longest period was selected. Altogether, 23 (96%) agencies participated in the study.

Practitioner sample

We invited all team practitioners to complete survey packets. Overall, 182 of 223 (82%) practitioners participated. Site-level participation rates ranged from 67% to 100%. The final sample consisted of 153 practitioners with at least six months of employment on the treatment team.

Data collection

The study procedures were approved by the university's institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from program directors, team leaders, and practitioners. During 2005 the first author conducted on-site visits to collect data from the team leader and practitioners in the form of semistructured interviews and survey packets. As part of the contract to the state's technical assistance center ( 34 ), trainers conducted day-long fidelity assessments during the study period.

Measures

Agency control. A semistructured questionnaire was administered to team leaders, who reported the percentage of consumers in their caseload who were receiving each of four forms of agency control—involuntary commitment to outpatient services; agency as the representative payee; intensive medication monitoring, defined as depot injection of psychotropic medication or daily oral medication monitoring, by the treatment team; and agency-supervised housing, defined as residences owned or leased by the agency. In addition to documenting these individual control practices, we intended to create a composite index to profile agencies' overall control. However, because of low internal consistency (Cronbach's α =.32), results for this index are not reported.

We also collected data on the use of intrusive substance use monitoring (that is, Breathalyzers or urine screenings given at least monthly). However, because teams infrequently reported this practice (for example, 59% of teams did not use this type of agency control at all), substance use monitoring was excluded from subsequent analyses.

Consumer caseload variables. Team leaders provided the percentages of persons on the team's caseload who had the following three characteristics: diagnosed as having schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, actively abusing substances, and recently hospitalized. Active substance abusers included individuals judged by the team to be in the precontemplation, contemplation, or preparation stages of change readiness in regard to their substance use ( 36 ). Recent hospitalization was defined as having been hospitalized in a state or private institution for either a psychiatric or substance use disorder in the previous three months.

Practitioner variables. Background information on practitioners was obtained through a survey instrument. Highest level of education achieved was assessed with a 9-point scale, with a score of 1 indicating less than 12 years of education, a score of 5 indicating a bachelor's degree, and a score of 9 indicating a doctorate degree. A new scale, the pessimistic attitudes scale, was developed by using six items from a preexisting scale ( 37 ) and then adding two items assessing attitudes about medication management and independent living. The eight-item checklist was completed by practitioners. Higher scores reflected greater pessimism. The internal consistency for this scale was acceptable (Cronbach's α =.77).

Program variables. We assessed fidelity to the assertive community treatment model with the 28-item Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Scale ( 29 ). A widely used scale, its psychometric properties have been well studied ( 38 ). This scale discriminates between assertive community treatment programs and usual case management services ( 29 ). It has excellent interrater reliability (r=.99) and is sensitive to change over time ( 39 ). Its predictive validity appears to be modest ( 40 ).

Three of the 12 items from the General Organizational Index ( 41 ) were selected to assess basic clinical practices: assessment, individualized treatment planning, and individualized treatment. This scale has been found to have high interrater reliability (r=.94) across 160 independent assessments. In the study reported here, the three selected items had good internal consistency (Cronbach's α =.83).

For both scales, assessment involves a multimodal approach to gather data, including chart reviews, observations of team meetings, and interviews with various staff and consumers. These data are then used to make ratings on behaviorally anchored 5-point scales, where higher scores reflect greater program fidelity and higher quality of basic clinical practices.

Data analysis

We first determined whether aggregation of practitioner-level data to the team level was statistically indicated based on the intraclass correlation coefficient ( 42 ). The intraclass correlations—.51 (N=153) for pessimistic attitudes and .30 (N=124) for education—were considered acceptable given the sample size ( 43 ). Thus mean practitioner scores were used as a team-level measure.

All variables were examined for distributional features, such as outliers and extreme skew. In general, the variables approximated normality. All analyses were also examined using nonparametric statistics, with similar results. Pearson correlations were used to assess all bivariate relationships. We also controlled for significant consumer caseload variables using partial correlations. Given the exploratory nature of this study, we used an alpha level of .05. All analyses were conducted with SPSS, version 15.0.

Results

Overall, the 23 treatment teams averaged 8.7±2.7 practitioners (excluding the psychiatrist on each team) serving 49.7±18.5 consumers. Caseload sizes ranged from 17 to 97 consumers. The mean practitioner-to-consumer ratio was 1.0 to 5.7±1.2. Sixty-five percent (N=15) of the teams were located in an urban area. Of the 153 practitioner participants, 81% (N=124) were frontline staff and the remaining 19% (N=29) were in leadership roles—that is, team leader or psychiatrist. Background characteristics of practitioners are summarized in Table 1 . The typical practitioner was a 41-year old Caucasian woman with a bachelor's degree and 11 years experience in the mental health field. No significant correlations were found between agency control and these team-level demographic characteristics.

|

Data distributions for key variables are presented in Table 2 . All four agency control measures showed wide variability across sites. Among these four practices, the most commonly used was designating the team as the representative payee. One-quarter of the teams were designated as the representative payee for at least 58% of their consumer caseload. Intensive medication monitoring was the next most frequently used control, with one-quarter of the teams intensively monitoring medications for at least 56% of the caseload. Agency-supervised housing and involuntary outpatient commitment were used with a minority of consumers. One-quarter of the teams had at least 37% of their consumer caseload under an involuntary outpatient commitment and at least 24% living in agency-supervised housing. Two teams had an exceptionally high proportion of their caseload living in agency-supervised housing (60% and 71%). Correlations among the four agency control practices were not significant (for involuntary outpatient commitment, correlations were .01 for agency as representative payee, .19 for intensive medication monitoring, -.03 for agency-supervised housing; for agency as representative payee, the correlation was .36 for intensive medication monitoring and .35 for agency-supervised housing; for intensive medication monitoring, the correlation was -.10 for agency-supervised housing).

|

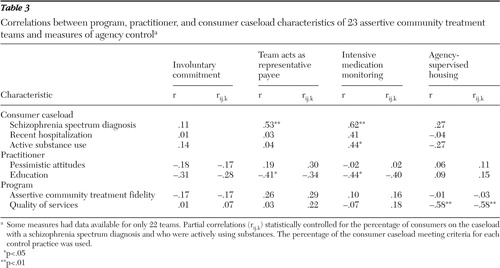

As shown in Table 3 , the percentage of consumers on the caseload with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder was strongly associated with the team's being the representative payee and intensive medication monitoring. Active substance use was also associated with intensive medication monitoring. Recent hospitalization was not associated with agency control.

|

With regard to practitioner characteristics, teams with more educated practitioners used representative payeeship and intensive medication monitoring less frequently. The strength of these associations was attenuated when the percentage of consumers on the caseload with a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder and the percentage with active substance use were statistically controlled for. Pessimistic attitudes of practitioners were not associated with agency control. With regard to program characteristics, quality of services was negatively associated with agency-supervised housing. Fidelity to the assertive community treatment model was not associated with agency control.

Discussion

This statewide survey documented wide variability among assertive community treatment teams in the scope of agency control. Teams varied greatly in how much control they employed across the four assessed practices, with representative payeeship and intensive medication monitoring used most frequently.

We assume that by having greater control, the team is better positioned to use restrictive interventions and potentially coerce consumers into accepting treatment or changing a maladaptive behavior. However, excessive and indiscriminate use of agency control is not the only example of a departure from good clinical practice. Some teams may assume little control not out of respect for consumer's autonomy but because they provide few services in general. Furthermore, some practices are driven by convenience, finances, or both rather than by consumer needs or goals. For instance, the less frequently used practices of agency-supervised housing and involuntary outpatient commitment are likely more susceptible to influences external to the team, such as lack of resources in the case of housing and local judicial practices in the case of commitment proceedings. Regarding housing, 16 participating agencies (70%) owned housing, whereas only two teams (9%) reported neither owning nor leasing housing. Our findings indicate that agency control is not a unitary concept, and we assume that external factors such as these accounted for weak associations between many of the control practices. Thus the agency control practices provide valuable descriptive information about the team's practices, but additional contextual information—for example, local legislature and agency policy—must be considered when interpreting these data.

Ideally, agency control is determined primarily by consumer attributes; some consumers may prefer that teams provide greater supervision and some simply need such supervision to safely live in the least restrictive environment. Indeed, the single strongest predictor of agency control was the proportion of consumers on the caseload with a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Also, teams were more likely to use agency control if they served a greater proportion of consumers who were actively using substances.

Contrary to assertions that assertive community treatment is inherently coercive, no relationship between program fidelity and agency control was found, although a more rigorous test of equivalence is needed, with an adequate sample size. The quality of basic clinical practices fundamental to any program—for example, person-centered treatment planning—was associated with less frequent use of agency-supervised housing but not of other control practices.

Teams staffed with more educated practitioners served as the representative payee for fewer consumers and used intensive medication monitoring less often. It may be that less educated staff are more inclined to employ authoritarian styles of intervening, as suggested by other research ( 44 , 45 ). We also speculate that more educated teams deliberate more as a group about when to initiate or discontinue agency control measures.

This study has a number of limitations. The generalizability of the study's findings may be limited because of the idiosyncrasies of Indiana's mental health system. For instance, consumer-to-staff ratios were exceptionally low as a result of local certification standards and funding mechanisms; however, we found no significant correlations between this ratio and any agency control measure. Also, the small sample limited the statistical power.

This body of research would be strengthened by future studies examining services across regions, comparing assertive community treatment to other program models in agency control practices and examining agency control in context of consumers' perceptions of coercion.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the emerging body of literature on coercion by providing benchmarks for the use of restrictive practices in community mental health. Benchmarks help researchers, clinicians, and administrators identify when a practice is under- or overused. Excessive use of control should be cause for concern and could denote an attribute of the team itself—for example, paternalism—not the situational needs of the consumers served. The findings from this study indicate that assertive community treatment teams vary a great deal in their use of agency control and that this variation is not associated with fidelity to the model.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grants 5F31MH75526-02 and T32MH019117 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by the American Psychological Foundation Todd E. Husted Memorial Dissertation Award. The authors thank the Indiana assertive community treatment teams for their eager participation and helpful comments and Michelle Pensec Salyers, Ph.D., Jeffery Swanson, Ph.D., and Marvin Swartz, M.D., for their feedback and suggestions throughout this study.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. National Consensus Statement on Mental Health Recovery. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005Google Scholar

2. Diamond RJ: Coercion and tenacious treatment in the community: applications to the real world, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment: A New Frontier in Mental Health Law. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

3. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS: Effects of legal mechanisms on perceived coercion and treatment adherence among persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:629–637, 2003Google Scholar

4. Lidz CW, Hoge SK, Gardner W, et al: Perceived coercion in mental hospital admission: pressures and process. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1034–1039, 1995Google Scholar

5. Monahan J, Redlich AD, Swanson J, et al: Use of leverage to improve adherence to psychiatric treatment in the community. Psychiatric Services 56:37–44, 2005Google Scholar

6. McGrew JH, Wilson RG, Bond GR: An exploratory study of what clients like least about assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services 53:761–763, 2002Google Scholar

7. Lucksted A, Coursey RD: Consumer perceptions of pressure and force in psychiatric treatments. Psychiatric Services 46:146–152, 1995Google Scholar

8. Neale MS, Rosenheck RA: Therapeutic limit setting in an assertive community treatment program. Psychiatric Services 51:499–505, 2000Google Scholar

9. Hanrahan P, Luchins DJ, Savage C, et al: Representative payee programs for persons with mental illness in Illinois. Psychiatric Services 53:190–194, 2002Google Scholar

10. Korman H, Engster D, Milstein BM: Housing as a tool of coercion, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment: A New Frontier in Mental Health Law. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

11. Allen M: Separate and Unequal: The Struggle of Tenants With Mental Illness to Maintain Housing. Washington, DC, National Clearinghouse for Legal Services, 1996Google Scholar

12. Angell B: Measuring strategies used by mental health providers to encourage medication adherence. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 33:53–72, 2006Google Scholar

13. Susser E, Roche B: "Coercion" and leverage in clinical outreach, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment: A New Frontier in Mental Health Law. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

14. Roberts LW, Geppert CMA: Ethical use of long-acting medications in the treatment of severe and persistent mental illnesses. Comprehensive Psychiatry 45:161–167, 2003Google Scholar

15. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, et al: Effects of involuntary outpatient commitment on subjective quality of life in persons with severe mental illness. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 21:473–491, 2003Google Scholar

16. Rain SD, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC: Perceived coercion and treatment adherence in an outpatient commitment program. Psychiatric Services 54:399–401, 2003Google Scholar

17. Solomon P: Research on the coercion of persons with severe mental illness, in Coercion and Aggressive Community Treatment: A New Frontier in Mental Health Law. Edited by Dennis D, Monahan J. New York, Plenum, 1996Google Scholar

18. Rosenheck R, Neale MS: Therapeutic limit setting and six-month outcomes in a Veterans Affairs assertive community treatment program. Psychiatric Services 55:139–144, 2004Google Scholar

19. Wennberg JE: Understanding geographic variations in health care delivery. New England Journal of Medicine 340:52–53, 1999Google Scholar

20. Gomory T: Programs of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT): a critical review. Ethical Human Sciences and Services 1:147–163, 1999Google Scholar

21. Fisher DB, Ahern L: Personal Assistance in Community Existence (PACE): an alternative to PACT. Ethical Human Sciences and Services 2:87–92, 2000Google Scholar

22. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392–397, 1980Google Scholar

23. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 9:141–159, 2001Google Scholar

24. Dixon L: Assertive community treatment: twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatric Services 51:759–765, 2000Google Scholar

25. Salyers MP, Tsemberis S: ACT and recovery: integrating evidence-based practice and recovery orientation on assertive community treatment teams. Community Mental Health Journal 43:619–641, 2007Google Scholar

26. Appelbaum PS, Le Melle S: Techniques used by assertive community treatment (ACT) teams to encourage adherence: patient and staff perceptions. Community Mental Health Journal 44:459–464, 2008Google Scholar

27. Moser L: The importance of therapeutic relationships in the program of assertive community treatment: development of a client satisfaction measure. Master's thesis. Normal, Illinois State University, Department of Psychology, 2000Google Scholar

28. Gerber GJ, Prince PN: Measuring client satisfaction with assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services 50:546–550, 1999Google Scholar

29. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:216–232, 1998Google Scholar

30. Adams N, Grieder D: Treatment Planning for Person-Centered Care: The Road to Mental Health and Addiction Recovery. Burlington, Mass, Elsevier Academic, 2005Google Scholar

31. Young AS, Forquer SL, Tran A, et al: Identifying clinical competencies that support rehabilitation and empowerment in individuals with severe mental illness. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 27:321–333, 2000Google Scholar

32. Hromco JG, Lyons JS, Nikkel RE: Mental health case management: characteristics, job function, and occupational stress. Community Mental Health Journal 31:111–125, 1995Google Scholar

33. Pulice RT, Huz S, Taber T: Academic training and case management services in New York State. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 19:47–50, 1991Google Scholar

34. Salyers MP, McKasson M, Bond GR, et al: The role of technical assistance centers in implementing evidence-based practices: lessons learned. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 10:85–101, 2007Google Scholar

35. Moser LL, DeLuca NL, Bond GR, et al: Implementing evidence-based psychosocial practices: lessons learned from statewide implementation of two practices. CNS Spectrums 9:926–936, 2004Google Scholar

36. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Burton HL, et al: A scale for assessing the stage of substance abuse treatment in persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:762–767, 1995Google Scholar

37. Grusky O, Tierney K, Spanish MT: Which community mental health services are most important? Administration and Policy in Mental Health 17:3–16, 1989Google Scholar

38. Winter JP, Calsyn RJ: The Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Scale (DACTS): a generalizability study. Evaluation Review 24:319–338, 2000Google Scholar

39. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Whitley R, et al: Fidelity outcomes in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project. Psychiatric Services 58:1279–1284, 2007Google Scholar

40. Bond GR, Salyers MP: Prediction of outcome from the Dartmouth ACT Fidelity Scale. CNS Spectrums 9:937–942, 2004Google Scholar

41. Bond GR, Drake RE, Rapp CA, et al: Individualization and quality improvement: two new scales to complement measurement of program fidelity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, in press, DOI 10.1007/ s10488-009-0226-yGoogle Scholar

42. Bliese PD: Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: implications for data aggregation and analysis, in Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations. Edited by Klein KJ, Kozlowski SW. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2000Google Scholar

43. Brown ME, Trevino LK: Socialized charismatic leadership, values congruence, and deviance in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology 91:954–962, 2006Google Scholar

44. Heaney CA, Burke AC: Ideologies of care in community residential services: what do caretakers believe? Community Mental Health Journal 31:449–462, 1995Google Scholar

45. Salyers MP, Tsai J, Stultz TA: Measuring recovery orientation in a hospital setting. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31:131–137, 2007Google Scholar