Impact of a Mental Health Training Course for Correctional Officers on a Special Housing Unit

In the past two decades the concept of the control unit, or secure housing unit, popularly known as "supermax," has become popular among U.S. correctional authorities. Although there is some debate as to what constitutes a supermax unit, in 2006 the Urban Institute reported that 95% of prison wardens surveyed agreed that a supermax unit consisted of "a stand-alone unit or part of another facility and is designated for violent or disruptive inmates. It typically involves single-cell confinement for up to 23 hours per day for an indefinite period of time. Inmates in supermax housing have minimal contact with staff and other inmates" ( 1 ).

Typically, the stated rationale for such units is the need to house the most difficult and dangerous offenders in an environment that minimizes the risk of trouble for the other inmates and staff. Nearly every state now has at least one special housing unit, and several states and the federal prison system have built entire facilities, called supermax prisons, on this model ( 2 , 3 ). Intended for the most dangerous offenders, special housing units have become "home" to many inmates with mental illness, despite the efforts of mental health and civil rights advocates. A policy paper of the National Institute of Corrections in 1999 stated, "Insofar as possible, mentally ill inmates should be excluded from extended control facilities … much of the regime common to extended control facilities may be unnecessary, and even counter-productive, for this population" ( 4 ).

This recommendation was not followed, and the reality of the prevalence of offenders with mental illness in special housing units was evident in a 2004 monograph from the National Institute of Corrections, for it identified mental health as "the major issue emerging in supermax litigation" ( 5 ). The author of this report noted that in California, Ohio, and Wisconsin plaintiffs had successfully argued that some offenders should not be placed in a special housing unit because of mental illness and that placement in a special housing unit could cause serious mental illness. The report identified several steps to prevent liability, including screening out inmates with serious mental illness before referral to the special housing unit, ongoing monitoring of the mental status of inmates on the special housing unit, and the provision of adequate mental health care on the unit.

Over the past 20 years the prevalence of mental illness in jails and prisons has been a growing concern for state correctional agencies, state mental health agencies, and advocacy organizations. Systematic examinations of mental illness among inmates have reported a threefold greater prevalence of psychotic and mood disorders in the population behind bars, compared with the adult U.S. population ( 6 ). Overall, 10% to 15% of inmates are estimated to have a serious mental illness ( 7 ). Although provision of general medical care is a constitutional duty of correctional authorities ( 8 ), inmates with serious mental illness pose more challenges to administrators, compared with inmates with other chronic illnesses, because the symptoms of mental illness, especially psychosis, may cause disruptive behavior. Because maintenance of a secure and stable environment is a primary concern for correctional authorities, disruptive behavior typically results in administrative consequences, up to and including segregation. In state prisons, offenders with mental illness are more likely than those who do not have a mental illness to be written up for breaking institutional rules (58% versus 43%), and they are also more likely to be charged with an assault (24% versus 14%) ( 9 ). Offenders with mental illness are thus more likely to be housed in more restrictive settings, including special housing units. Once assigned to a special housing unit, offenders typically do not do well clinically, particularly if they have a mental illness ( 10 ), and they also pose significant management challenges to staff of special housing units; they often suffer additional administrative penalties as a consequence.

The Indiana Department of Correction has two special housing units—the first opened in the Westville facility in 1993, and the second, the site of this project, opened in the Carlisle facility in 1995 ( 11 ). The Carlisle facility is currently classified as high-medium security by the Indiana Department of Correction, and it has both minimum- and maximum-security units; the Westville facility is classified as medium security and has minimum-, medium-, and maximum-security units ( 12 ). The number of offenders with mental illness in the Carlisle special housing unit, which has a capacity of 280, was tracked from 1996 to 2003; the number increased steadily since it opened, from 49 (18% of capacity) in 1996 to 173 (62% of capacity) in 2003 (personal communication, Carlisle Department of Correction superintendent, 2006). Throughout the study, mental health care to offenders housed on the Carlisle special housing unit was provided by a Department of Correction contractor and included psychiatric and psychology services. However, assessments, monitoring, and programming were limited because of the challenges of communicating through the food slot in the cell door or by the difficult logistics of arranging the movement of an offender from his cell to another location either within or off the special housing unit.

The National Alliance on Mentally Illness (NAMI) is an advocacy organization dedicated to improving the lives of people afflicted by serious and persistent mental illness ( 13 ). In 2003 an inmate at the Carlisle special housing unit wrote to the Indiana chapter of NAMI (NAMI-Indiana) to report the difficult conditions faced by offenders with mental illness in the special housing unit. At the invitation of the superintendent, NAMI members subsequently toured the facility. After further discussions, NAMI-Indiana was invited to develop and provide a training program on mental illness for the correctional staff on the special housing unit. This report discusses the effect of this educational intervention on the number of incidents reported by correctional staff on the special housing unit in their monthly reports, both before and after the NAMI training.

Methods

The training program consisted of five two-hour sessions, given over five consecutive weeks. The first session introduced the correctional officers to the major categories of psychiatric disorders (substance abuse disorders, personality disorders, mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders) by describing the diagnostic criteria for these disorders in clear language, using illustrative examples from clinical practice and popular movies, and encouraging questions and discussion. Session 2 built on the first session by focusing on the biology of mental illness; the speaker used clear diagrams and neuroimaging to outline how brain cells communicate using neurotransmitters and how mental illness affects the chemistry, structure, and metabolism of the brain. Session 3 provided an overview of the treatment of mental illness, with discussions of the major groups of psychiatric medications and how they affect the neurotransmitter systems, as well as discussion of psychological treatments. The fourth session focused on how to interact effectively with people with mental illness and incorporated a consumer-speaker from NAMI's In Our Own Voice program ( 14 ). The curriculum concluded with a session that reviewed and integrated all of the previous sessions and was co-led by a senior supervisor from the Department of Correction. The preparation of the curriculum was coordinated by an administrator from NAMI-Indiana. The curriculum authors were all NAMI-Indiana members and included medical school psychiatry faculty, university basic sciences faculty, a prison administrator, family members, and consumers. The curriculum was designed to be interactive—all of the speakers encouraged questions and discussion—and role-playing exercises for the participants were included. The curriculum was field-tested before the Carlisle training at a meeting of Indiana correctional officials and at a training conference hosted by NAMI-Indiana.

At the invitation of the Carlisle superintendent, NAMI-Indiana provided this training in February and March 2004 to all of the correctional officers assigned to the Carlisle special housing unit. The training was provided at the official training site for the facility, which was located outside the walls of the prison. The special housing unit staff was split in half for the training, and each of the five sessions was provided twice each week. The NAMI members who developed each portion of the curriculum provided the training in person, with the assistance of the NAMI-Indiana coordinator and the Carlisle training supervisor. Attendance was closely monitored by the Department of Correction with sign-in sheets, because the training was deemed mandatory by the prison administration. The correctional officers came in before shift change, stayed after the end of their shift, or came in on days off to attend the training, and they were paid accordingly. Each attendee was asked to complete anonymously a pretest before each session and a posttest and a feedback form at the end of each session. The training was repeated by videoconference in June and July 2005, and all staff who had joined the special housing unit since the initial training attended, along with staff from other units at the Carlisle facility.

The administrators at the Carlisle special housing unit routinely prepared standard monthly quality assurance reports, which included a summary sheet noting the unit census, the total number of incidents for the month, the number of times force was used by unit staff on offenders, and the number of incidents of battery by bodily waste on custody staff. The Carlisle superintendent shared the summary sheets with NAMI-Indiana, beginning nine months before the start of the first training and continuing until the special housing unit underwent a major reorganization nearly two years later. Although the full reports generated by the facility included specific information about the circumstances of each incident and the inmates and correctional officers involved, the research presented here was based only on the summary sheets, because of concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. As a result, it could not be determined whether any given incident involved an inmate with a serious mental illness or a particular correctional officer.

The overall number of incidents and the number of each type of incident, dating from July 2003 to April 2006, were entered into an electronic spreadsheet. The number of total incidents, incidents of use of force, and incidents of battery by bodily waste were then statistically compared for the nine months before and after each of the two training sessions, using Student's t test ( 15 ).

This research project was granted exempt status by the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Institutional Review Board.

Results

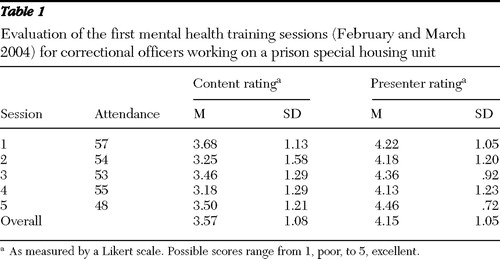

Attendance at the first mental health training, which took place in February and March 2004, ranged from 48 to 57 staff per session ( Table 1 ). Attendance was determined by a count of the pre- and posttests turned in for each session; these tests were required for participants to receive training credit from the Department of Correction. Participants were also asked to rate anonymously the content of each session and the presenter, as well as the overall course, using a Likert scale; possible scores ranged from 1, poor, to 5, excellent. The initial training was well received by the correctional officers, with a mean rating of 4.15 for the course presenters and a mean rating of 3.57 for the overall course content. A total of 34 staff from the Carlisle facility attended the second training in June and July 2005. The attendance numbers, evaluations, and test performances of the staff of the special housing unit for this training could not be determined, because the staff of the special housing unit were part of a larger group from the Carlisle facility and the attendance sheets did not note each officer's unit assignment.

|

In the nine months before the initial training, the special housing unit was over census for two months, and the mean±SD monthly census was 275.7±5.1 (98.5% of capacity). The special housing unit was over census for eight of the nine months after the initial training, with a mean monthly census of 282.4±2.7 (100.9% of capacity). The monthly census was lower in the nine months before the second training (273.3±6.0, 97.6% of capacity) and declined further in the nine months after the second training (243.6±29.1, 87.0% of capacity). As noted above, the prevalence of mental illness on the special housing unit was 62% in 2003; however, this statistic was not determined in subsequent years, because of a change in supervisory staff (personal communication, Carlisle Department of Correction superintendent, 2008).

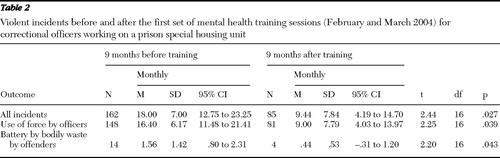

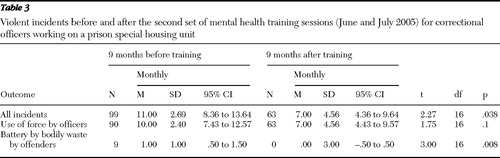

In the nine months after the first training, the number of total incidents, number of incidents involving use of force, and incidents of battery by bodily waste on the special housing unit all declined significantly, compared with the nine months before the training ( Table 2 ). In the nine months after the second training, the total number of incidents and the number of incidents of battery by bodily waste declined significantly, compared with the nine months before the training ( Table 3 ). Similar data were sought for the entire Carlisle facility, but only battery by bodily waste was tracked during the study period; all but one battery by bodily waste incident occurred on the special housing unit.

|

|

Discussion

Role and training of correctional officers

Correctional officers can play a vital role in ensuring appropriate treatment of offenders with mental illness, but they generally receive little training in mental health issues and have a professional culture that is quite different from that of mental health professionals ( 16 , 17 ). The NAMI-Indiana training program attempted to bridge this cultural gap by educating the correctional officers assigned to a secure housing unit about mental illness. On the basis of the decline in the number of incidents after the training, the NAMI-Indiana program was successful in reducing both the use of force by the correctional officers, as well as the number of assaults by bodily waste on the officers. The training was also well received by the staff of the special housing unit, despite their initial reluctance to participate in the training.

Little has been written on the role of correctional officers in the management of offenders with mental illness in jails and prisons. Kropp and colleagues ( 16 ), in a 1989 article, found that the correctional officers assigned to a maximum-security pretrial unit felt that working with offenders with mental illness added stress to their jobs, and although they were confident in their abilities to handle the general population in the jail, nearly all of them were interested in further training on how work with offenders with mental illness.

In recent years, only two articles have been published on the specific topic of mental health training for correctional officers. Appelbaum and colleagues ( 17 ), writing about working in the Massachusetts state prison system, noted the difficult working conditions faced by correctional officers, particularly the threat of violence, and identified the differing professional cultures of security staff and mental health staff as a major issue. They also observed that many correctional officers and many mental health staff work together effectively and share common goals of decent and humane treatment of inmates. They emphasized that correctional officers could and should be recognized as members of the multidisciplinary treatment team for offenders with mental illness, particularly on residential treatment units. Massachusetts offers collaborative training sessions for correctional officers about suicide prevention and mental illness, but this program was not described in detail and no outcomes were described.

Dvoskin and Spiers ( 18 ) described the culture of the community inside prison walls and argued that correctional officers could play important roles in the provision of mental health services to offenders, including talking with offenders in a therapeutic manner, talking about the offenders as part of the mental health consultation process, and observing medication effects and side effects. The authors specifically identified special housing programs, including administration segregation units, as places where correctional officers could play a vital role in the identification and management of mental illness; they also emphasized the importance of training to improve the relationship between custody staff and mental health professionals. The authors included descriptions of programs that successfully involved correctional officers in mental health roles, but none of these were accompanied by a reference to a published article that described the program or its outcomes.

Correctional officers play a vital role in maintaining safety and security in prisons, and they are subject to many stresses, including long hours, low pay, and the risk of violence, which is their highest concern ( 19 ). In addition, correctional officers have reported high psychological demands on the job, accompanied by low social support, a low sense of control, and feelings of insecurity ( 20 ). When one considers the challenges of their work environment, it is perhaps not surprising that correctional officers who work on special housing units have been reported to be physically and psychologically abusive to inmates under their supervision ( 2 , 3 ).

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics notes, "Correctional officers learn most of what they need to know for their work through on-the-job training" ( 21 ). Indiana requires only that correctional officers be high school graduates and have three years of work experience; as a result, the recruits generally have little experience with or knowledge about working with people with serious mental illness, even after completing the preservice academy. At the time of the study, Indiana correctional officers received only a very basic orientation to mental health issues in the preservice academy, consisting of 2.5 to 3.0 hours, out of more than three weeks of training, on working with offenders with mental illness, substance abuse, and developmental disabilities ( 22 ). The NAMI-Indiana curriculum on mental illness was designed to address this knowledge deficit and was well received by the correctional officers who attended the sessions.

More important, the NAMI training was associated with a significant decline in officers' use of force with offenders and in the number of attacks on the officers by the offenders. Although it is not possible to state with certainty how the training led to these beneficial results, the NAMI team attributed the decline in use of force to improved understanding of the offenders' mental illnesses and to the interacting skills emphasized in the latter part of the training. The reason for the decline in incidents of battery by bodily waste is less obvious, but in discussions between the NAMI team and staff of the Department of Correction, it was felt that the attention given to skills in interaction with people with mental illness helped in this area as well. Since battery by bodily waste is one of the few forms of retaliation available to offenders on special housing units, it is possible that the officers, by treating offenders with more understanding, may have decreased the frustration and anger that lead to battery by bodily waste.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the training of the entire staff of a special housing unit and the availability of objective data directly related to safety issues from before and after the training. Weaknesses of the study include the retrospective nature of the study and the lack of a control population. Although the NAMI-Indiana team that created the curriculum was interested in outcomes, the initial focus was on the response of the officers to the training itself; the incident reports did not become available until well after the training had been completed. The Westville special housing unit could have been a good control population for this study, but this facility declined to respond to a request for data on incidents of use of force and battery by bodily waste. The overall Carlisle facility could also have served as a control population, even though it housed both minimum and maximum-security offenders. Unfortunately, the only data available for the entire facility for the study period covered just battery by bodily waste; this report was not particularly useful for control purposes, because over the course of more than two years, only one battery by bodily waste occurred off of the special housing unit—which is clearly evidence of the troubled nature of the offenders on the unit, the disturbing impact of the special housing unit itself, or both.

In addition, as should be expected in a large prison facility, the NAMI training was not the only factor at work over the course of the study. The Indiana special housing unit underwent a number of changes before, during, and after the NAMI training (personal communication, Carlisle Department of Correction administrative staff, 2006). The administration of the unit changed before the training, as the sergeants were rotated off the unit and a new captain was assigned. In the months immediately after the training (April to June 2004), the Department of Correction gradually transferred selected offenders from the special housing unit to a new program at the prison psychiatric facility, during which time some offenders became more disruptive in an attempt to be placed on the transfer list; as a result, there were high numbers of use of force in two of these three months. However, Carlisle Department of Correction staff noted that the offenders who were transferred were not those who had been involved in the incidents reported in previous months. The transfers were then replaced with new offenders from the waiting list for the special housing unit. Finally, in the fall of 2004, several months after the training, several unit staff received disciplinary action, including arrest, for abusive behavior; this investigation began months before the discipline occurred.

Clearly, each of these factors could have had an impact, for better or for worse, on the culture of the special housing unit. The change in supervisory staff could have set the stage for a positive response to the training; although senior management supported the training, the faculty noted obvious difficulty in engaging the officers in the training, particularly in the early sessions, despite the positive ratings given by attendees. The change in offender population could have removed the offenders who were most involved in reported incidents and thus affected the perceived effectiveness of the training, but a unit administrator noted that the transferred offenders were not those involved in prior incidents. Finally, the investigation and later removal of officers on charges of abuse could have affected the atmosphere on the unit either positively (encouraging for more professional behavior) or negatively (aggravating an already difficult work environment). Although the officers who were removed left the unit more than six months after the initial training, the numbers of incidents declined significantly shortly after the first training ended and rose modestly after their departure, only to decline again after the second training of officers new to the special housing unit. This pattern suggests that the removal of the officers was not the driving force in the decrease in the number of incidents on the special housing unit and that the mental health training played an important role in that decrease.

Conclusions

The NAMI training curriculum, which provided ten hours of education on mental illness to all of the correctional officers who worked on an Indiana special housing, or supermax, unit, was associated with a significant decrease in the use of force by the correctional officers and battery by bodily waste on the officers by offenders. These results suggest that providing mental health training to all of the correctional officers on a prison unit can lead to safer working conditions for the correctional officers and safer living conditions for offenders.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The NAMI-Indiana members who created and provided the mental health training curriculum were Kellie Meyer, M.A., Alan Schmetzer, M.D., Joan LaFuze, Ph.D., Joseph Vanable, Ph. D., Alan Finnan, Ph.D., Mike Kempf, Christine Jewell, B.S., and George Parker, M.D.

The author reports no competing interests.

1. Mears DP: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Supermax Prisons. Washington, DC, Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center, Mar 2006Google Scholar

2. Kamel R, Kerness B: The Prison Inside the Prison: Control Units, Supermax Prisons and Devices of Torture: Briefing Paper. Philadelphia, American Friends Service Committee, 2003Google Scholar

3. Abramsky S, Fellner J: Ill-Equipped: US Prisons and Offenders With Mental Illness. New York, Human Rights Watch, 2003Google Scholar

4. Riveland C: Supermax Prisons: Overview and General Considerations. Washington, DC, National Institute of Corrections, Jan 1999Google Scholar

5. Collins WC: Supermax Prisons and the Constitution: Liability Concerns in the Extended Control Unit. NIC accession no 019835. Washington, DC, National Institute of Corrections, Nov 2004Google Scholar

6. Pinta ER: The prevalence of serious mental disorders among US prisoners. Correctional Mental Health Report 1:33–34, 44–47, 1999Google Scholar

7. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483–492, 1998Google Scholar

8. Estelle v Gamble, 429 US 97 (1976)Google Scholar

9. James DJ, Glaze LE: Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Pub no NCJ 213600. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Sept 2006Google Scholar

10. Haney C: Mental health issues in long-term solitary confinement and "supermax" confinement. Crime and Delinquency 49:124–156, 2003Google Scholar

11. Fellner J, Mariner J: Cold Storage: Super-Maximum Security Confinement in Indiana. New York, Human Rights Watch, Oct 1997Google Scholar

12. Adult Facilities. Indianapolis, Indiana Department of Correction. Available at www.in.gov/idoc/2332.htm Google Scholar

13. About NAMI. Arlington, Va, National Alliance on Mental Illness. Available at www.nami.org/template.cfm?section=about_nami Google Scholar

14. In Our Own Voice. Arlington, Va, National Alliance on Mental Illness. Available at www.nami.org/template.cfm?section=in_our_own_voice Google Scholar

15. Data Entry: Student's T-Test. Collegeville, Minn, College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University, Collegeville, Minn. Available at www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/t-test_bulk_form.html Google Scholar

16. Kropp PR, Cox DN, Roesch R, et al: The perceptions of correctional officers toward mentally disordered offenders. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 12:181–188, 1989Google Scholar

17. Appelbaum KL, Hickey JM, Packer I: The role of correctional officers in multidisciplinary mental health care in prisons. Psychiatric Services 52:1343–1347, 2001Google Scholar

18. Dvoskin JA, Spiers EM: On the role of correctional officers in prison mental health. Psychiatric Quarterly 75:41–59, 2004Google Scholar

19. Finn P: Addressing Correctional Officer Stress: Programs and Strategies: Issues and Practices in Criminal Justice. Pub no NCJ 183474. Washington, DC, National Institute of Justice, Dec 2000Google Scholar

20. Ghaddar A, Mateo I, Sanchez P: Occupational stress and mental health among correctional officers: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Occupational Health 50:92–98, 2008Google Scholar

21. Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2008–2009. Washington, DC, US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available at www.bls.gov/oco/ocos156.htm Google Scholar

22. Fiscal Impact Statement. Indianapolis, Ind, Legislative Services Agency, Office of Fiscal and Management Analysis, Jan 29, 2004. Available at www.in.gov/legislative/bills/2004/PDF/FISCAL/SB0271.002.pdf Google Scholar