A National Survey of Psychiatric Mother and Baby Units in England

The postpartum period is a time of high risk of deterioration in a woman's mental health. Two recent large population-based studies found the combined incidence of hospitalization for an episode of psychosis or bipolar disorder during the postpartum period to be .10% ( 1 , 2 ). The risk of hospitalization for an episode of either is particularly high among women with a previous psychotic or bipolar illness. For women with a psychiatric hospitalization before pregnancy, the incidence of postpartum episodes of psychosis and bipolar disorder is 9.24% and 4.48%, respectively; approximately 90% of these episodes occur within the first four weeks of delivery ( 2 ). Women with psychotic episodes in the postpartum period have complex treatment needs because of the potential impact of their illness on the relationship with their infant and their ability to parent and because of the complex decision making involved in weighing the risks and benefits of psychotropic medication ( 3 ).

Women are also at risk of nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders in the perinatal period. The prevalence of nonpsychotic depressive illness in the postnatal period varies according to definition, thresholds, and measures used, but a meta-analysis of 59 studies found the average prevalence to be 13% (95% confidence interval=12.3%–13.4%) ( 4 ). Although the concept of postnatal depression is widely recognized, it is less often realized that the symptoms of depression are also common during pregnancy; depression scores have been shown to be higher in the third trimester of pregnancy than in the first two months postpartum ( 5 , 6 ).

Maternal mental illness has a significant impact on obstetric outcome; the social, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive development of children; and the parental relationship. An almost twofold higher risk of fetal death or stillbirth among offspring of women with psychosis has been shown ( 7 ), as well as a strong link between prenatal anxiety and marked behavioral or emotional problems among offspring at four years ( 8 ). Cognitive delay and lower IQ scores are also seen among children of mothers with postnatal depression ( 9 , 10 ), even after adjustment for potential confounders. Neglect of the child, suicide, and infanticide are rare but devastating outcomes. Indeed, recent Confidential Enquiries Into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom ( 11 , 12 ) reported that psychiatric disorders were a leading cause of maternal death.

The current recommended care for mothers with postpartum disorders is to keep the mother with the baby whenever possible, although this recommendation is relatively recent. In the first half of the 20th century, separation of mother and infant was considered to be the best practice, whether the mother was cared for in the home or an asylum ( 13 ). It was only in the late 1950s that this practice began to change and the first facilities to allow joint psychiatric admission were established in the United Kingdom ( 13 ). Since this time the type and number of facilities have varied ( 14 , 15 ), ranging from a single bed on a general psychiatric ward, where a baby may also be accommodated, to large separate wards with dedicated staff. The latter are generally referred to as mother and baby units (MBUs) although there is no accepted definition of what constitutes such a unit. In addition, there is no trial-based evidence for the effectiveness of MBUs ( 16 ), and there is little qualitative research examining the experiences of women in MBUs; however, a recent survey by a leading British mental health charity found that most women who were admitted to nonspecialized units felt isolated ( 17 ). In addition, many who were admitted to MBUs considered that the outcome for themselves and their family would have been much less positive if they had not been admitted to a specialized unit ( 17 ). Despite this, some regard MBUs as expensive and segregative ( 18 ).

Nonetheless, recent policy guidelines in the United Kingdom have advocated that MBUs should be further developed ( 19 , 20 ), and the 2007 U.K. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health ( 21 ) recommends that women who need inpatient care for a mental disorder within 12 months of childbirth should normally be admitted to a specialized MBU, unless there are specific reasons for not doing so. Despite these recommendations there is little evidence about what services an MBU should provide or what services are currently provided within MBUs. This study aimed to establish the number of MBUs in England, their operating procedures, and the clinical characteristics of their inpatients.

Methods

In England a national cross-sectional survey of alternatives to standard acute inpatient care was conducted in 2005; details of the methodology have been described by Johnson and colleagues ( 22 ). Multiple methods were used to identify services, including examination of the Mental Health Service Mapping for Working Age Adults in England ( 23 ), telephone calls to all mental health trusts in England inquiring whether services were available for their area, Google Internet searches, and a consultation with a variety of expert sources, including MIND and Rethink (national mental health voluntary organizations). As part of this, a number of facilities that admitted mothers and babies were identified.

All services were contacted and invited to participate in a structured interview with a researcher (HG or BL-E) who used a questionnaire specifically designed for the study to cover the main clinical and organizational characteristics of services. [The questionnaire is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] Interviews were usually conducted over the telephone with the manager of the service, who received and had the opportunity to prepare answers to the questions in advance. Each participant was also asked to provide nonidentifying details of the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of all residents in their service on the preceding night. As a check on how comprehensive the identification of MBUs had initially been, respondents were asked to name any other MBUs that they were aware of in the surrounding area: this yielded only two previously unidentified MBUs, confirming the impression that the initial strategy identified most MBUs nationally.

The criteria for an MBU for this study consisted of inpatient psychiatric units where mothers and babies could be admitted that had at least four beds and were entirely separate from any other ward. All were staffed 24 hours per day, seven days per week, by dedicated multidisciplinary staff to care for both the mother and her baby. This is a new definition incorporating existing guidelines from the U.K. Department of Health and NICE ( 21 ). Ethical approval for this study was received from the Joint Research Ethics Committee at the Institute of Psychiatry and South London and Maudsley NHS (National Health Service) Foundation Trust.

Data were entered into SPSS, version 14, and a descriptive statistical analysis was carried out, with calculations of means and standard deviations for continuous variables and proportions and percentages for categorical variables.

Results

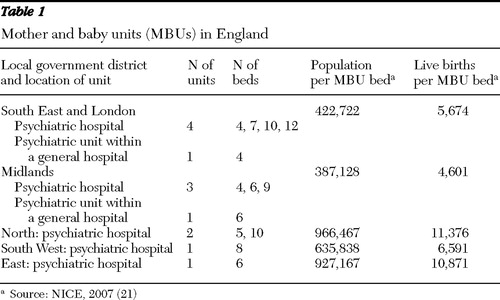

Twenty-six facilities that accommodated mothers and babies were identified. Thirteen were excluded from the final analysis, because they did not fulfill the study's operationalized criteria for an MBU. Two of the facilities that were excluded had only day services; others had fewer beds and shared premises and staff with general adult or geriatric psychiatry wards. In total, 13 MBUs were identified throughout England ( Table 1 ): five in the South East and London, four in the Midlands, two in the North, one in the South West, and one in the East. All except one unit participated in this study, and thus the results presented are for the 12 units that participated.

|

Premises, management, and funding

All MBUs were part of the public sector and occupied a whole ward. Ten MBUs were in a psychiatric hospital, and two were in a psychiatric unit within a general hospital. Nationally, there were 91 beds, and the size of the units, measured in number of beds for mothers, ranged between four and 12 beds (mean±SD 7.0±2.6) ( Table 1 ). Mothers had their own bedrooms on all but one unit. Seven units (58%) had a defined catchment area from which they accepted referrals, although these varied considerably in terms of geographical size. Five units (42%) accepted out-of-area referrals, contingent on funding. The mean estimated bed occupancy (data missing for two units) in 2005 was 77.5%±16.7% (range 50%–100%). The mean length of stay in 2005 was 56.0±19.6 days (range 28–90), on the basis of actual and estimated data. One unit did not allow an admission to exceed 180 days, but all other units did not stipulate a maximum stay.

Referrals

Accepted routes of referral were diverse. Each unit was asked to name the three most common sources of referral. The most common source of referral was from outpatient psychiatry services (community mental health teams, psychiatrists, and crisis resolution or home treatment teams). The second most common source was from general practitioners (although two units did not accept referrals via this route). The third most common source was from social workers, midwives, obstetric wards, or health visitors (that is, a nurse or midwife trained to assess the health of individuals, families, and the wider community), and the least common source was from inpatient psychiatry services.

Other sources included caregivers, mental health workers outside the NHS (for example, day center staff or hostel staff), and police and criminal justice agencies. One unit accepted self-referrals. Once a referral had been received, seven units (58%) could usually admit the same day if a bed was available. The assessment and admission procedure for the other five units took longer.

Admission criteria

The population each service was intended to accommodate was reasonably consistent throughout the country. Eleven MBUs (92%) stated that their priority was women experiencing a crisis that would otherwise result in an admission to a standard general acute ward; thus an admission to the MBU would avoid separation of the mother and baby. One unit was aimed at those experiencing a crisis that was not likely to result in admission to a general ward. Another targeted women initially admitted to a general acute ward who needed further residential care before going home. A small proportion of the units accepted pregnant women. One unit had a dedicated bed for those in any trimester, and two units accepted women in the final trimester only. One unit would accept pregnant women if they also had a baby aged up to 12 months.

The youngest age for a mother admitted by any unit was 14 years, another's youngest age was 16 years, and the youngest age for all other units was 18 years and above. Most also had an admission criterion relating to the age of the baby. Almost universally, the maximum age was 12 months, although one unit allowed children up to three years. Of the 56 inpatients on MBUs on the day of the survey, 35 (63%) were white, ten (18%) were Asian, seven (13%) were African or African Caribbean, and four (7%) were other or mixed race. All units could accept detained patients directly from the community, and on the day of the survey, ten patients (18%) were compulsorily detained under the Mental Health Act (1983) (English legislation covering the compulsory detention of patients requiring treatment in psychiatric hospitals).

Almost half (N=26, 46%) of all MBU inpatients on the day of the survey were already on the caseload of the local NHS psychiatric service when they were admitted, and almost the same proportion (N=25, 45%) had a history of previous psychiatric admission, although it was not clear whether this was related to childbearing. Twenty-five (45%) women were experiencing psychotic symptoms when they were admitted.

Care and support

Medical care was provided by a consultant psychiatrist and trainees employed within the service. A physical examination and medication review were standard, and all units had the capability to draw blood. Staff kept and gave medications to the mother when they were due. However, one unit had a mother who was expected to self-medicate because she was nearing discharge and was going to live in independent living quarters that were part of the MBU.

Regarding the availability of individual psychological treatments or psychotherapy, five units (42%) were not able to provide any. Three (25%) provided only cognitive-behavioral therapy, and the remaining units (N=4, 33%) offered cognitive-behavioral therapy and one or more other therapies, including cognitive-analytic therapy and psychodynamic therapy.

All units that offered some form of individual psychological therapy also offered family therapy (N=6, 50%) or couple therapy (N=1, 8%). In total, each woman could receive between one and five hours per week of psychological therapy, with the most frequent limit being two hours. This was undertaken by a variety of professionals, including clinical psychologists, nurse therapists, and registered mental nurses.

All units also had access to occupational therapy or organized recreational activities, with a large range of occupational and recreational activities available. Three units offered alternative therapies, including aromatherapy and body massage, and three units offered baby massage.

Nine units (75%) had advocacy services available, and the same proportion had a welfare rights or benefits advisor. In all but one unit (that is, 11 units, 92%), staff could help with problems with accessing housing and social services, such as obtaining forms and help with completing forms for benefits claims or housing applications. Facilities for caregivers were also common. Ten units (83%) provided them with education about mental health problems, and five (42%) had support groups for caregivers.

Risk management

All units used standardized risk assessment forms, and most (N=9, 75%) had specific entry criteria that stated that the mother must not be violent or have any active intent of violence. Half (N=6, 50%) explicitly stated that they did not accept women with current drug and alcohol problems, particularly if this was the primary diagnosis.

All but one unit—which could only provide one-to-one care for a few hours (usually fewer than 12)—could provide one-to-one care for as long as necessary. If a client were at a very high risk of self-harm or harming others, despite the support of the service, nine units (75%) would transfer the patient to a local NHS general adult ward, therefore separating mother and baby. This would be without the client's agreement, if the level of concern were high.

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to identify specialized psychiatric inpatient facilities that can admit mothers and babies throughout England and to look in detail at their clinical and organizational characteristics. This was part of a larger study looking at all alternatives to inpatient stay, and the methodology likely ensured that all MBUs were identified. Although the term "mother and baby unit" is widely used, there are no standardized criteria against which to judge whether a service classifies as one, and the criteria we propose are based on current guidelines from national agencies.

The regional variation in provision was striking, with the greatest number of beds located in the South East and London and the lowest ratio of live births per MBU bed in the Midlands. Nationally, only around half of the estimated number of beds required are available ( 21 ), and in areas where services do not exist, women are either admitted to general adult wards and separated from their baby or they are sent to out-of-area placements with implications for family and friends' maintaining contact. This is important given that the average length of stay was almost eight weeks. The population all units intended to accommodate was reasonably consistent, but it is notable that two units chose to accept women with less severe mental illness. Overall, 45% of women had psychotic symptoms on admission. This is a sicker group of women than the one described by Buist and colleagues ( 24 ), who reported on the characteristics of women admitted to MBUs in Australia, and this may explain the longer average length of stay described here, compared with the Australian study.

It is of note that accepted referral routes were diverse, with some units considering all avenues and others accepting referrals only from professionals in secondary care services. The decision to accept pregnant women was also variable, with one unit dedicating a bed to this population but most not allowing them to stay on the ward. A significant proportion of women had psychotic symptoms, and on average, 18% of women on the units were detained under a Section of the Mental Health Act (1983). This suggests that a significant proportion of women are who are admitted to MBUs are severely ill or are at risk to themselves or others, which has risk-management implications.

Occupational therapy was widely available, with a diverse range of conventional and alternative therapies, including baby massage. There is no consensus regarding recommended occupational therapies for this population. However, the discrepancy in provision of psychological services on the MBUs, with 42% not providing any form of psychological intervention, is notable. It is generally accepted that the best outcome of a severe mental illness is achieved with a combination of pharmacological and psychological interventions. The units were not specifically asked about types of interventions available to address the mother-infant relationship, because data were collected as part of a larger study of mental health services, but no units mentioned such interventions when they were asked what other types of psychological treatments were available. Although there are no published evaluations of such interventions on MBUs, we know anecdotally that such interventions are being developed on a few of these units and that at least two units are currently evaluating these interventions.

Strengths of this study include the comprehensive coverage of all services in England and the systematic collection of data by trained research workers. Limitations include the lack of independent validation of data obtained from the telephone interviews with senior staff of the participating units and the failure of one unit to participate.

Conclusions

Despite a lack of randomized controlled trials to show their effectiveness, MBUs are currently advocated by a number of U.K. policy documents for the care of women with severe mental illness in the year after childbirth. The current clinical and operating characteristics of these services in England are highly variable. Nationally, there are far fewer beds than needed, and there is an inequity of access throughout the country. There is little consistency regarding premises, funding, management, accepted referral routes, severity of illness of admitted women, and support for caregivers. In particular, the provision of psychological intervention is highly variable. Qualitative and quantitative prospective cohort studies are required to identify the most useful and valuable components of MBUs, particularly investigating interventions specific to the perinatal period, to help in the planning of future provision of these units. Consensus standards for MBU care, developed by the U.K. Perinatal Quality Network, have been recommended by NICE ( 25 ). However, empirically based standards are needed to ensure that MBUs provide the best possible outcomes at this critical time for mothers and their families.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This report presents independent research commissioned by grant SDO/75/2004 from the U.K.National Institute for Health Research(NIHR) Service Development and Organisation R&D Programme. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the U.K. Department of Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, et al: New parents and mental disorders: a population-based registered study. JAMA 296:2582–2589, 2006Google Scholar

2. Harlow BL, Vitonis A, Sparen P, et al: Incidence of hospitalization for postpartum psychotic and bipolar episodes in women with and without prior pregnancy or prenatal psychiatric hospitalizations. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:42–48, 2007Google Scholar

3. Viguera AC, Emmerich AD, Cohen LS: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital: case 24-2008: a 35-year-old woman with postpartum confusion, agitation, and delusions. New England Journal of Medicine 359:509–515, 2008Google Scholar

4. O'Hara M, Swain A: Rates and risk of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry 8:37–54, 1996Google Scholar

5. Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, et al: Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ 323:257–260, 2001Google Scholar

6. O'Hara M, Zekoski E, Philipps L, et al: Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: comparison of childbearing and non-childbearing women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 99:3–15, 1990Google Scholar

7. Webb R, Abel K, Pickles A, et al: Mortality in offspring of parents with psychotic disorders: a critical review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:1045–1056, 2005Google Scholar

8. O'Connor T, Heron J, Beveridge M, et al: Maternal antenatal anxiety and children's behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. British Journal of Psychiatry 180:502–508, 2002Google Scholar

9. Sharp D, Hay D, Pawlby S, et al: The impact of postnatal depression on boys' intellectual development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 36:1315–1336, 1995Google Scholar

10. Hay D, Pawlby S, Sharp D, et al: Intellectual problems shown by 11-year-old children whose mothers had postnatal depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 42:871–879, 2001Google Scholar

11. Why Mothers Die: 2000–2002. London, Confidential Enquiry Into Maternal and Child Health, 2005Google Scholar

12. Saving Mothers' Lives: 2003–2005. London, Confidential Enquiry Into Maternal and Child Health, 2007Google Scholar

13. Howard L: The separation of mothers and babies in the treatment of postpartum psychotic disorders in Britain 1900–1960. Archives of Women's Mental Health 3:1–5, 2000Google Scholar

14. Prettyman R, Friedman T: Care of women with puerperal psychiatric disorders in England and Wales. BMJ 302:1245–1246, 1991Google Scholar

15. Oluwatayo O, Friedman T: A survey of specialist perinatal mental health services in England. Psychiatric Bulletin 29:177–179, 2005Google Scholar

16. Joy C, Saylan M: Mother and baby units for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews CD006333, 2007Google Scholar

17. Oates M, Rotherera I: Out of the Blue? Motherhood and Depression. Broadway, London, MIND, 2006. Available at www.mind.org.uk Google Scholar

18. Barnett B, Morgan M: Postpartum psychiatric disorder: who should be admitted to which hospital? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 30:709–714, 1996Google Scholar

19. Perinatal Maternal Mental Health Services, Council Report CR88. London, Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2000Google Scholar

20. Puerperal Psychosis and Postnatal Depression. Edinburgh, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2002. Available at www.sign.ac.uk Google Scholar

21. NICE Clinical Guideline 45: Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health Clinical Management and Service Guidance. London, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007Google Scholar

22. Johnson S, Gilburt H, Lloyd-Evans B, et al: Acute in-patient psychiatry: residential alternatives to hospital admission. Psychiatric Bulletin 31:262–264, 2007Google Scholar

23. Glover G, Barnes D, Wistow R, et al: Mental Health Service Mapping for Working Age Adults. Stockton on Tees, UK, North East Public Health Observatory, 2004. Available at www.nepho.org.uk/mho Google Scholar

24. Buist A, Minto B, Szego K, et al: Mother-baby psychiatric units in Australia: the Victorian experience. Archives of Women's Mental Health 7:81–87, 2004Google Scholar

25. Commissioning Guide for Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health Services. London, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008. Available at www.nice.org.uk Google Scholar