Use of Buprenorphine for Addiction Treatment: Perspectives of Addiction Specialists and General Psychiatrists

Legislative approval by the U.S. Congress in 2000 of the prescription of Schedule III, IV, and V controlled substances in office-based practice for treatment of opioid addiction expanded the range of treatment options for opiate-dependent individuals by offering a medication therapy alternative to methadone. Buprenorphine, which is sold under the trade name of Suboxone (a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone) or Subutex (buprenorphine alone), is the first of such medications. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002 for detoxification and maintenance treatment of opiate dependence.

Buprenorphine may be prescribed by physicians after they receive a waiver from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) ( 1 ). Buprenorphine provides a prescription-based treatment to accompany counseling, which facilitates office-based therapy. Goals include bringing more opiate-dependent people, particularly highly motivated individuals, into treatment and increasing the number of physicians addressing this problem. In the past, new pharmacotherapies such as naltrexone have not been widely accepted into addiction treatment ( 2 , 3 ). It was hoped that through educational programs directed to the physician community and supported by the federal government and professional organizations, this new therapy would disseminate widely and rapidly to both addiction specialists and other clinicians ( 4 ).

Six years after approval of buprenorphine in addiction treatment, it is not clear how well these goals have been accomplished. According to SAMHSA, by 2006 more than 10,000 physicians had been trained and 7,000 certified to prescribe buprenorphine ( 4 ). Surveys of physicians who have been certified to prescribe buprenorphine indicate that complexity of induction, medication costs, and regulatory limits have posed barriers to prescribing ( 5 ). Moreover, an estimated 104,640 patients had been inducted on buprenorphine as of March 2005, which is only a fraction of the population that might be helped by this new therapy ( 4 ). Researchers examining acceptance of new treatments have focused primarily on either the characteristics and treatment decisions of individual physicians ( 5 , 6 ) or the characteristics of the organizations providing treatment ( 7 ) but have rarely considered them in concert. The research reported in this article surveyed physicians who have and who have not sought certification to prescribe buprenorphine. Information was gathered on clinician characteristics associated with prescribing, the views of clinicians on the role of their affiliated organizations in their buprenorphine prescribing practices, and barriers to prescribing.

Background

In 2005 an estimated 1.2 million persons were dependent on opiates ( 8 ). The burden of opiate dependence is heavy, both for the addicted individual and for society. Substitution therapy is effective for detoxification and maintenance, but methadone can be administered only in highly regulated environments that may discourage treatment entry ( 9 ). Only 20% of opiate-dependent patients received treatment in 2005 ( 10 ). The unmet need for treatment makes office-based approaches attractive because they expand the base of providers and venues at which opiate-dependent persons can receive substitution therapies, and they provide a setting for maintenance treatment that does not have the inconvenience or stigma of daily dispensing as does methadone.

The Drug Addiction Treatment Act (DATA) of 2000 established a system that allows for office-based prescribing of medications approved by the FDA to treat opiate addiction. Physicians obtain waivers by receiving eight hours of training, acquiring addiction specialty certification, conducting research on approved drugs, or meeting state regulations ( 1 ). In 2002 FDA approved buprenorphine for the treatment of opiate dependence, making it the first drug available via the DATA waiver program ( 11 ). In clinical trials buprenorphine has been shown to reduce craving, the percentage of opioid-positive urine samples, and self-reported addiction severity compared with placebo ( 12 , 13 ). In a study of 1,203 psychiatrists conducted on the eve of buprenorphine's FDA approval, West and colleagues ( 6 ) found that 81% were not comfortable prescribing office-based opiate agonist treatment. The size of a psychiatrist's substance abuse caseload was found to be associated with the level of comfort with office-based treatment, but only 57% of the 41 certified addiction psychiatrists reported comfort with such an approach. Similarly, Koch and colleagues ( 7 ) found that among substance abuse treatment facilities, certified opioid treatment programs were more than twice as likely as noncertified programs to offer buprenorphine. This suggests that prescribing of buprenorphine may be related to the treatment philosophy of these facilities—a medical approach—as well as to program type.

Physicians and facilities interdependently influence one another in the decision to incorporate new treatments. Previous research has found that organizational support of adoption of naltrexone was strongly associated with its adoption by physicians, but the mechanisms by which organizations supported prescribing, and the interrelationships between physicians and their organizations, was less clear ( 2 ). This article extends earlier research on adoption of substance abuse treatment pharmacotherapy and follows a framework that recognizes the importance of physicians, their work environment and treatment organizations, and the public policy environment in contributing to adoption ( 2 , 14 ).

The following research questions were addressed: What are the personal, practice, treatment organization, and market characteristics that are associated with receipt of training, receipt of a waiver, and prescription of buprenorphine in office-based settings? How well has buprenorphine been accepted outside the realm of addiction treatment specialists by general psychiatrists and why? What are the barriers to and facilitators of prescribing buprenorphine?

Methods

Survey instrument

Researchers developed and fielded a 14-page mail survey with an option to respond via the Internet. The survey was designed to elicit physicians' attitudes toward and practices in regard to prescribing buprenorphine. The survey consisted of the following domains: personal characteristics, practice and treatment organization characteristics, patient characteristics, substance abuse treatment philosophy and approaches used, and attitudes and prescribing practices specifically in regard to buprenorphine. The survey was pilot-tested outside the study markets with two addiction expert consultants and two psychiatrists, revised, and then fielded from October 2005 through February 2006. Physicians were sent a $25 incentive in advance to respond to the survey and an additional $25 upon completion.

Sample

The target population for the survey was addiction treatment specialists (psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists) and other psychiatrists in four market areas: Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and Miami. These areas were chosen because they have a large number of emergency department visits by heroin-addicted individuals and represent different geographic regions ( 15 ). In each of these four markets, two specific groups were surveyed: physicians with a specialty in addiction treatment and additional psychiatrists in the market area who were not members of the specialty organizations. Specialists included all members of two professional organizations—the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) and the American Association of Addiction Psychiatrists (AAAP)—identified through mailing lists and any physician in the market area who was listed on the SAMHSA physician finder Web site as having been certified to prescribe buprenorphine. ASAM and AAAP members may be board certified in addiction treatment, board-certified psychiatrists, or physicians trained in other specialties. All have expressed a specific interest in addiction medicine by joining these professional organizations.

Psychiatrists were also drawn from the American Psychiatric Association (APA) master file in each market area; the number of psychiatrists in the master file for the four market areas ranged from 374 to 1,295. For each area, 150 psychiatrists were randomly selected by use of the SAS procedure PROC SURVEYSELECT. To eliminate those who did not have any reason to prescribe buprenorphine, the sampled psychiatrists were first screened with a question asking whether they currently had any patients in their practice being treated for substance abuse (by them or elsewhere).

The nonspecialist sample was limited to psychiatrists (rather than all physicians) because we expected that they would be more likely than other physicians to know about and have interest in prescribing buprenorphine. Finally, if a physician was not included in the above groups but was the medical director of a treatment organization surveyed in our companion study of adoption by treatment organizations ( 16 ), he or she filled out a survey. These facility directors were grouped with addiction specialists in the analysis.

After we eliminated undeliverable mailings (27 addiction specialists and 37 psychiatrists who were not addiction specialists), 7% of specialists and 29% of non-addiction specialist psychiatrists were deemed ineligible because they did not have patients in their practice who were being treated for substance abuse or they were no longer practicing. The final sample of complete usable responses was 495 physicians: 224 non-addiction specialist psychiatrists (57% response rate) and 271 addiction specialists (72% response rate), of which 32 were facility directors. Sixteen percent of respondents (spread evenly across states) completed the Web survey.

Analysis

The major research interest was in identifying factors that are predictive of obtaining certification or training to prescribe buprenorphine and of prescribing it. The starting points for these analyses are two survey questions: physicians were asked whether they obtained certification to prescribe buprenorphine, either by attending a training session or by obtaining a waiver to prescribe, and whether they, in fact, prescribe buprenorphine (a dichotomous-choice question asking whether they prescribe or not). Overall rates of certification and prescribing were calculated, and then through bivariate analysis, prescribing rates were compared by physician characteristics, setting, organization, attitude, and market (t tests of differences in means or chi square tests for categorical variables). Prescribing rates were compared first between addiction specialists and non-addiction specialist psychiatrists and, second, with respect to reported characteristics of affiliated treatment organizations. In addition, physicians' reports of facilitators and barriers to prescribing were examined.

In a final step, multivariate logistic models were constructed to identify physician and organizational characteristics predictive of outcomes of interest: buprenorphine certification and prescribing. As regressors in the models, in addition to personal characteristics of physicians, the item in each domain in our survey that was theorized to be most predictive of outcomes and that correlated with outcomes was selected. This research was approved by Brandeis University's institutional review board.

Results

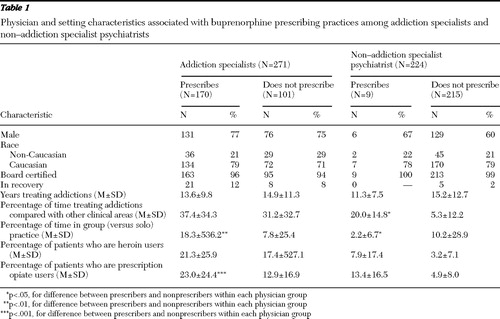

As shown in Table 1 , among both addiction specialists and non-addiction specialist psychiatrists, respondents were mostly male and nearly all were board certified, with an average of 14 or 15 years of experience treating addictions. Addiction specialists reported treating an average of 56 patients for opiate dependence in the past month, and other psychiatrists reported an average of 2.4 (not shown). Addiction specialists reported that more than 20% of their patients were dependent on heroin, alcohol, or prescription opiates. Non-addiction specialist psychiatrists had many fewer patients with opioid addictions, but nearly 20% of their patients were alcohol dependent.

|

Prescribing buprenorphine

Large differences were found between addiction specialists and non-addiction specialist psychiatrists in the percentage who had received training or were exempt and in the percentage who prescribed buprenorphine. A total of 235 addiction specialists (87%) had received training or were exempt because they had participated in clinical trials. A total of 170 specialists, 72% of those trained or certified, were prescribing buprenorphine to their patients at the time of the survey. In strong contrast, among non-addiction specialist psychiatrists who were treating patients for addictions, 29 (13%) had received training or were exempt, and nine (4%) were prescribing buprenorphine.

Although physicians' personal characteristics were not significantly associated with prescribing of buprenorphine, several practice characteristics were ( Table 1 ). Addiction specialists who had adopted buprenorphine spent more time in group practice and had more patients who were prescription opiate users. The small number of prescribers limits the usefulness of significance testing for non-addiction specialist psychiatrists, but prescribing for this group appears to be associated with a greater percentage of current clinical time spent treating addictions and less time in group practice.

To examine the relationship between payment source and prescribing, we asked physicians to describe the proportion of patients covered by private insurance, state block grant funds, Medicare, Medicaid, and self-pay (not shown). There were some differences in the mix of payment sources for patients receiving substance abuse treatment between prescribers and nonprescribers. For example, prescribers and nonprescribers reported similar mean percentages of Medicare patients (both 9%) and Medicaid patients (21% and 20%, respectively). However, prescribers reported lower proportions of privately insured patients (21% compared with 27%), state block grant fund patients (3% compared with 6%), and patients who were provided care at no charge (free care) (9% compared with 12%) and higher proportions of self-pay patients (36% compared with 21%) (p<.01 for all comparisons).

Addiction specialists compared with other psychiatrists

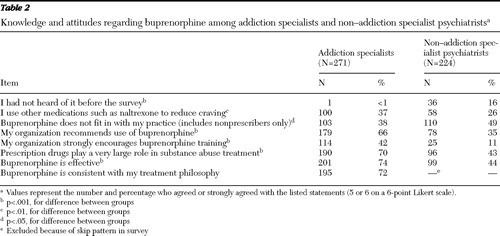

To understand better why psychiatrists who were treating individuals with addiction problems but who were not addiction specialists were not as likely to prescribe buprenorphine, we compared responses to survey items reflecting their knowledge and attitude in regard to buprenorphine ( Table 2 ). Knowledge and attitudes were significantly different between addiction specialists and other psychiatrists. When asked about the source from which they first heard about buprenorphine, 16% of non-addiction specialist psychiatrists indicated that they had not heard about buprenorphine before the survey, compared with less than 1% of addiction specialists.

|

There were also strong differences in practice types: fewer non-addiction specialist psychiatrists worked in organizations that recommended use of buprenorphine (35% compared with 66%, p<.001) or encouraged buprenorphine training (11% compared with 42%, p<.001); fewer agreed or strongly agreed with the prescription of other medications, such as naltrexone, to reduce craving (26% compared with 37%, p<.01). Fewer non-addiction specialist psychiatrists believed buprenorphine is effective (44% compared with 74%, p<.001). Perhaps most important is that non-addiction specialist psychiatrists treated far fewer opiate patients than did addiction specialists; the average number treated in the past month was two for non-addiction specialist psychiatrists compared with 56 for addiction specialists. It appears that buprenorphine may be better accepted than other substance abuse pharmacotherapies by addiction specialists: two-thirds of addiction specialists prescribed buprenorphine, whereas only 37% prescribed other anticraving medications, such as naltrexone for alcohol dependence.

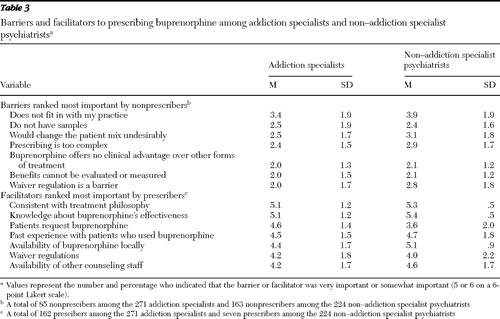

Physicians were also asked to rate the importance of a number of barriers and facilitators to prescribing buprenorphine on a scale from 1, not important, to 6, very important. Important factors for nonprescribers were considered barriers, and important factors for prescribers were facilitators ( Table 3 ). Surprisingly, rankings were similar for addiction specialists and non-addiction specialist psychiatrists. Although mean scores for barriers were lower than those for facilitators, among top barriers for both groups were "It does not fit in with my practice," "It would change the patient mix undesirably," and that "prescribing is too complex." For addiction specialists, lack of samples also provided a strong barrier, and for non-addiction specialist psychiatrists, the waiver regulation (having to obtain certification in order to prescribe) was perceived as a strong barrier. In both groups, most important in the decision to prescribe buprenorphine was knowledge and consistency with treatment philosophy. Patient requests and local availability were also rated as highly important. Waiver regulation was also an important consideration, even for prescribers. Also, for physicians who prescribed buprenorphine, cost was not rated as a highly important factor in their decision.

|

Role of organizational affiliation and treatment programs

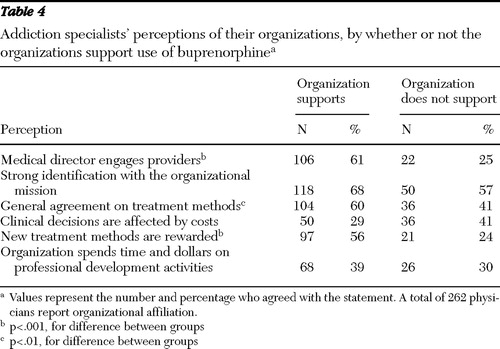

Analysis of the role of organizations in treatment was limited to the 271 addiction specialists, because they were more likely to be closely aligned with a specialty substance abuse treatment organization that might have a policy about buprenorphine. Overall, perceived organizational support was strongly associated with adopting and prescribing buprenorphine, but there were exceptions. Among addiction specialists who reported that their affiliated organization was supportive of buprenorphine use, three-fourths (74%) prescribed it, much higher than the rate of prescribing for study participants who believed that their organization was not supportive of buprenorphine (44%). This finding also indicates that nearly half of physicians in organizations that had not adopted buprenorphine prescribed it anyway.

The survey found that an organization's support for the use of buprenorphine was significantly associated with other characteristics, as perceived by physicians ( Table 4 ). Among physicians who reported that their organizations supported training and use of buprenorphine, two-thirds reported that they worked in organizations that had a medical director who engaged providers in clinical decisions, compared with only one-fourth of physicians who reported that their organizations did not support training and use of buprenorphine (p<.001). Physicians in organizations supportive of buprenorphine were also more likely to report a general agreement on treatment methods (p<.01) and to feel that new treatments were encouraged (p<.001).

|

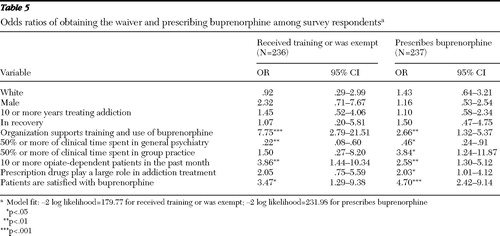

Multivariate analysis of physician and organizational factors

Table 5 shows the results of multivariate logistic models using the common set of predictors. Physician characteristics (gender, race, years in practice treating addictions, and whether physicians themselves were in recovery) were not predictive of receipt of training or of prescribing buprenorphine, but many of the practice-related predictors were. In the logistic model of receipt of training (or exempt from training), significant variables included organizational support (odds ratio [OR]=7.75, p<.001), at least 50% of clinical time in general psychiatry (negative predictor, OR=.22, p<.01), ten or more opiate-dependent patients in the past month (OR=3.86, p<.01), and patient satisfaction with buprenorphine (OR=3.47, p<.05). In the accompanying logistic model predicting buprenorphine prescribing, organizational support (OR=2.66, p<.01) and ten or more opiate-dependent patients in the past month (OR=2.58. p<.01) were significant and patient satisfaction with buprenorphine treatment was highly significant (OR= 4.70, p<.001). Significant variables also included the view that prescription drugs play a large role in treatment (OR=2.03, p<.05), at least 50% of clinical time in general psychiatry (negative predictor, OR=.46, p<.05), and at least 50% of clinical time in group practice (OR = 3.84, p<.05).

|

Discussion

This survey, conducted three years after buprenorphine was approved and marketed for office-based treatment, is the first to include both physicians who have received waivers to prescribe buprenorphine and those who have not. The goal of the survey was to understand barriers to prescribing this new addiction treatment. However, the study was a preliminary examination of use of a new treatment and is limited to particular markets and not necessarily generalizable to all physicians who treat opiate-dependent patients, such as general practitioners. Results indicate that most addiction specialists have adopted it, but beyond addiction specialists, few other clinicians have incorporated it into practice.

These findings also reveal the importance of organizational influence and patient satisfaction, which probably also reflects patient demand, in adopting buprenorphine. The study also identified differences in behavior and characteristics of organizations that support use of buprenorphine and those that do not. The differences in the models predicting certification and predicting prescribing showed important factors that facilitate prescribing: organizational support appears to be more important in obtaining certification than in prescribing, and being in a group practice setting and strong patient demand are strong predictors of prescribing but not of receipt of training. Thus, in comparing predictors of training to those of prescribing, it appears that physicians may train or seek certification with less commitment to the role of medications in treatment, but they need to really believe in the effectiveness of buprenorphine if they are to prescribe.

Low prescribing rates beyond the core group of addiction specialists are consistent with other addiction pharmacotherapies ( 2 , 3 ) and reflect challenges predicted by others ( 6 ). The Center for Substance Abuse Treatment has endeavored to provide information and training to physicians to encourage use of buprenorphine in office-based practice. However, the fact that psychiatrists other than AAAP or ASAM members rarely prescribe it raises the concern of how well the message about buprenorphine and its advantages has been communicated. The survey also found that among addiction specialists, having spent more time in general psychiatry decreased the likelihood of prescribing buprenorphine. Although research indicates that pharmacological treatments are commonly prescribed by psychiatrists for patients with and without substance use disorders ( 17 , 18 ), there may be several reasons that buprenorphine has not been more widely prescribed by non-addiction specialist psychiatrists. Unlike many other medications prescribed by the psychiatric community, addiction treatment medications such as buprenorphine are most effective when used in a comprehensive recovery program. In particular, initial dosing of buprenorphine requires its on-site storage and availability and resources for extended monitoring of patients' response. Psychiatrists with limited clinical staff or those not affiliated with addiction treatment programs or recovery support systems may thus be reluctant to prescribe buprenorphine. In addition, psychiatrists unfamiliar with the safety features of the combined buprenorphine-naloxone preparation may be worried about the potential for abuse. Of critical importance is the fact that non-addiction specialist psychiatrists treat fewer patients with addictions than do addiction specialists, which may make it not worth their while to seek training and certification to prescribe buprenorphine.

Both addiction specialists and other psychiatrists ranked "does not fit with my practice" and "would change my patient mix" as important barriers and cost as less important, although the current cost of buprenorphine is $160 per month. It may merely be that some psychiatrists specialize in conditions unrelated to the use of medication-assisted treatments or, of greater concern, that certain psychiatrists do not want to treat opiate-addicted patients. Beyond the issues of medication-assisted treatment, stigma and stereotypes must be addressed to overcome these barriers.

Although knowledge about buprenorphine and a positive attitude toward the role of medications in addictions treatment are both necessary for prescribing, the treatment organization plays a critical role that cannot be ignored. As was found in studies mentioned earlier, the support of an organization is an important factor in adopting new addiction treatment medications. According to physicians, organizations that encourage prescribing of buprenorphine are more likely to be collaborative, reward new treatments, and value professional development.

Conclusions

The goal of office-based treatment of opiate dependence is to improve access and reduce unmet demand by bringing more people into treatment. Our study strongly suggests that more work must be done to familiarize physicians with buprenorphine, destigmatize opiate addiction, and bring additional providers into the treatment of addictions. Fulfilling the promise of office-based treatment may be difficult for two reasons. First, given the importance of organizational influences in prescribing, it is not clear how psychiatrists who are not affiliated with addiction treatment programs will have incentives to obtain training and prescribe buprenorphine. Second, it may be difficult for psychiatrists in solo or small group practice to provide both buprenorphine-based maintenance services and the more complex detoxification without the added resources provided by treatment programs and other facilities. However, as time passes, if more patients with addiction seek treatment in office-based settings, more providers may be willing to change practices to accommodate such patients.

Finally, to the extent that buprenorphine gains broader acceptance among providers, additional surveys are needed to address issues related to cost and access, because a large proportion of patients are not insured. These include determining whether insurers cover buprenorphine and under what restrictions and examining the cost of treatment, drug diversion in the community, and nonadherence to treatment. Thus, although office-based treatment offers a promising path to improved access, expanding addiction treatment through office-based practitioners promises to be a continuing challenge, warranting continued monitoring.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was funded by grant R01-DA-014578 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Physician Waiver Qualifications. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available at www.buprenorphine.samhsa.govGoogle Scholar

2. Thomas CP, Wallack SS, Lee S, et al: Research to practice: adoption of naltrexone in alcoholism treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 24:1–11, 2003Google Scholar

3. Mark TL, Kranzler HR, Poole VH, et al: Barriers to the use of medications to treat alcoholism. American Journal on Addictions 12:281–294, 2003Google Scholar

4. The Determinations Report: A Report on the Physician Waiver Program Established by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 ("DATA"). Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2006Google Scholar

5. Stanton A, McLeod C, Luckey B, et al: SAMHSA/CSAT Evaluation of the Buprenorphine Waiver Program. Presented at the annual research meeting of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, San Diego, May 5–7, 2006Google Scholar

6. West JC, Kosten TR, Wilk J, et al: Challenges in increasing access to buprenorphine treatment for opiate addiction. American Journal on Addictions 13(suppl 1):S8–S16, 2004Google Scholar

7. Koch AL, Arfken CL, Schuster CR: Characteristics of US substance abuse treatment facilities adopting buprenorphine in its initial stage of availability. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 83:274–278, 2006Google Scholar

8. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2005. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2006. Available at www.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/ICPSR/STUDY/04596.xmlGoogle Scholar

9. O'Connor PG, Fiellin DA: Pharmacologic treatment of heroin-dependent patients. Annals of Internal Medicine 133:40–54, 2000Google Scholar

10. Hser YI, Maglione M, Polinsky ML, et al: Predicting drug treatment entry among treatment-seeking individuals. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 15:213–220, 1998Google Scholar

11. Subutex and Suboxone approved to treat opiate dependence. FDA Talk Paper. Rockville, Md, US Food and Drug Administration, 2002. Available at www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/answers/2002/ans01165.htmlGoogle Scholar

12. Johnson RE, Eissenberg T, Stitzer ML, et al: A placebo controlled clinical trial of buprenorphine as a treatment for opioid dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 40:17–25, 1995Google Scholar

13. Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, et al: Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. New England Journal of Medicine 349:949–958, 2003Google Scholar

14. Rogers E: Diffusion of Innovations. New York, Free Press, 2003Google Scholar

15. Emergency Department Trends From DAWN: Final Estimates 1995–2002. ED Drug Episodes: Estimated Rates per 100,000 Population by Metropolitan Area by Half Year, Table 13.1. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2002. Available at http://dawninfo.samhsa.gov/olddawn/pubs9402/edpubs/2002final/files/pubtablesch13.xlsGoogle Scholar

16. Wallack SS, Thomas CP, Martin TC, et al: Substance abuse treatment organizations as mediators of social policy. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, in pressGoogle Scholar

17. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, Tanielian TL, et al: Psychiatric patients and treatments in 1997: findings from the American Psychiatric Practice Research Network. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:441–449, 1999Google Scholar

18. Wilk J, Marcus SC, West J, et al: Substance abuse and the management of medication nonadherence in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 194:454–457, 2006Google Scholar