Utilization and Costs of Antipsychotic Agents: A Canadian Population-Based Study, 1996–2006

Second-generation antipsychotics (clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine) became available on the Canadian market in the 1990s for the treatment of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Although clozapine has shown superiority to other agents in treatment-resistant schizophrenia ( 1 , 2 ), the efficacy of other second-generation agents appears to be comparable to the older antipsychotics (for example, haloperidol and phenothiazines) in controlling psychoses, but their safety profiles have mitigated concerns regarding the extrapyramidal side effects and tardive dyskinesia associated with the use of first-generation agents ( 3 , 4 ). As a consequence, with the exception of clozapine (because of its 1% risk for agranulocytosis), second-generation antipsychotics have been recommended as first-line treatment of psychotic and bipolar disorders ( 5 , 6 , 7 ). However, other serious adverse effects have been reported for the newer agents, such as weight gain, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, and their overall effectiveness has been subject to debate in recent times ( 8 , 9 , 10 ). It is important that relative risks and benefits associated with the choice of specific antipsychotic agents are carefully considered.

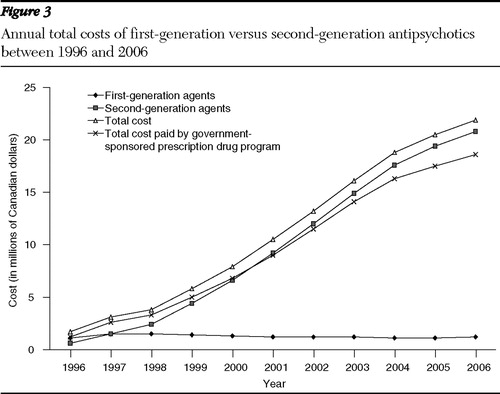

The second-generation agents are significantly more costly than first-generation antipsychotics, and expenditures accrued by their adoption have engendered widespread concern, particularly because questions remain to be addressed about their cost-effectiveness ( 11 , 12 ).

Numerous studies on the utilization of antipsychotic agents have been conducted in recent years and have documented that the second-generation antipsychotics are prescribed more frequently and to an increasingly larger patient population ( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ). Although some of these studies utilized data from administrative databases, most have referenced select samples ( 13 , 17 , 19 ), often in countries that lack comprehensive health care coverage ( 16 ); many were limited to clients of specific drug plans ( 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ).

For the study presented here, data from the Manitoba Population Health Research Data Repository provided a unique opportunity to describe the utilization of prescribed antipsychotic drugs from a population perspective, without the limitations imposed by differences in insurance coverage. This is the first report that describes the use of antipsychotic agents in the entire population of a Canadian province (Manitoba) and presents a cost assessment of these agents over the course of the past decade.

Methods

This population-based study received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba. The protocol was also approved by the Manitoba Health Information Privacy Committee. Administrative data regarding antipsychotic drug utilization between April 1, 1995, and March 31, 2006, were obtained from the Manitoba Population Health Research Data Repository housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (University of Manitoba, Winnipeg): the study was conducted in full compliance with the Privacy of Health Information Act in the province of Manitoba.

The Manitoba Health's Drug Program Information Network database captures over 90% of the population of the province (not exclusively the population covered by the government-sponsored drug programs) with the following caveats: the database does not include data for medications that patients receive during hospital stays, and it may underestimate prescriptions dispensed to First Nation (Native American) patients served by northern nursing stations ( 21 ).

Patient records are stored according to a scrambled personal health identification number in order to protect patients' privacy. All individuals receiving at least one prescription for an antipsychotic agent in any of the index years were included and constituted the "antipsychotic users" population. Index years were defined to cover periods from April 1 to March 31. No age restrictions were applied.

Generic names of specific antipsychotics included first-generation agents chlorpromazine, flupenthixol, fluphenazine, haloperidol, loxapine, methotrimeprazine, pericyazine, perphenazine, pimozide, pipotiazine, prochlorperazine, thioproperazine, thiothixene, thioridazine, trifluoperazine, and zuclopenthixol and second-generation agents clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone. Formulations available on the Canadian market during the study were identified by their unique drug identification number. Statistics Canada census data provided the number of residents in Manitoba, their gender, and their age group at each index year as reported on July 1 of each calendar year.

Temporal changes in antipsychotic drug utilization and costs were described by assessing population prevalence of use of antipsychotic medications and prescription costs, which were calculated per resident and per patient. Prevalence of use was estimated by using the number of individuals dispensed a prescription for an antipsychotic in a given year as the numerator while the census data served as the denominator.

Diagnoses were retrieved from medical and hospitalization files and identified by ICD-9 codes. Prescriptions were associated with users with specific diagnoses. Users were stratified by age group and agent used. Prescriptions were reported annually. No direct linkage between prescription and diagnosis was possible.

As in all Canadian provinces, the provincial government in Manitoba provides universal health coverage for all residents. Publicly funded health care insurance includes all "medically necessary" services, such as hospital care and physicians' visits. However, prescription drugs dispensed to community dwellers are not covered under the umbrella of "medically necessary" services, and provinces have historically taken different approaches to offering coverage for prescription drugs to their residents: restrictions are often applied in terms of age or income. Contrary to other provincial programs, the Manitoba Pharmacare program provides prescription drug coverage to all residents of Manitoba who register and are not covered by other provincial, federal, or private plans. This program pays 100% of all prescription costs after an income-based deductible is reached. Government-sponsored drug programs also include coverage for prescription drugs dispensed to individuals living in personal care homes (the Personal Care Home Program provides professional nursing care and personal care services to individuals who can no longer manage safely in their own home) and to clients of the Employment and Assistance Program (a provincial program of last resort for people who need help to meet basic personal and family needs); in these cases no deductible is implemented.

Total expenditures could be differentiated into portions covered by government-sponsored provincial drug programs and the out-of-pocket portion (paid by patients or by other third-party payers). Annual costs included the acquisition cost of the medications and the professional fees paid to the dispensing pharmacists. All costs were expressed in nominal Canadian dollars.

Summary statistics were used to describe prescription data as well as changes according to methods used in previous studies ( 22 ). SAS software package for Windows, version 9.0, was used for the analyses.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The province of Manitoba extends over an area of 647,797 square kilometers in central Canada. Its ethnically diverse population has remained relatively stable in the past decade (1996–2006), increasing only slightly from 1.13 million in 1996 to 1.18 million in 2006. [A table showing the population, the total number of antipsychotic users, and the number of antipsychotic users by sex and age over the study period is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.] More than 600,000 individuals reside in the urban area of the capital city, Winnipeg; the rest of the population dwells in smaller communities across rural Manitoba. The distribution of urban versus rural population has also been stable at 72% versus 28% over the past decade. Self-reported ethnicity includes more than 80% of European origin (British, Eastern European, French, German, and Irish), 10% of North American Indian (First Nation), and 5% of Métis (people of North American Indian and European ancestry). About 2% of the total population of Manitoba is of Icelandic ancestry. Age distribution changed with time, showing an increase in the 36–65 age group (from 34% of the total population in 1996 to 39% in 2006) and a decrease in the 19–35 age group (from 26% to 23%). [A table showing the population, the total number of antipsychotic users, and the number of antipsychotic users, by sex and age, over the study period is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.] The over 65 age group remained stable at 13%.

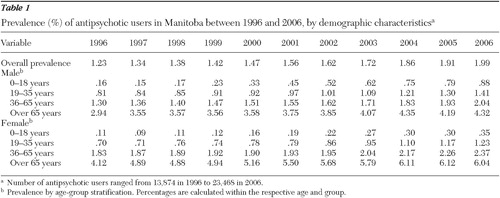

The number of patients filling at least one prescription for an antipsychotic agent increased from 13,874 in 1996 to 23,468 in 2006. Demographic characteristics (gender and age groups) of the antipsychotic users are also reported in Table 1 .

|

Antipsychotic utilization

Although the population of Manitoba increased only by 4% between 1996 and 2006, the prevalence of antipsychotic users increased by 62%, from 1.23% (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.21%–1.25%) in 1996 to 1.99% (CI=1.97%–2.02%) in 2006. Changes in prevalence of use according to gender and age group are reported in Table 1 .

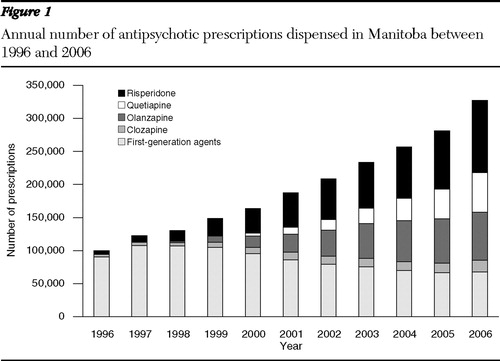

The total annual number of antipsychotic prescriptions filled in Manitoba increased by 227%, from 99,930 in 1996 to 327,121 in 2006 ( Table 2 ). The number of prescriptions for second-generation antipsychotics increased from 9,694 in 1996 (attributed only to the prescribing of clozapine and risperidone) to 259,376 in 2006. Prescriptions for first-generation agents reached a maximum of 107,575 in 1997 and progressively decreased to 67,745 in 2006. Prescriptions filled and numbers of unique antipsychotic users are reported in Figures 1 and 2 .

|

The most commonly prescribed agent within the group of the first-generation antipsychotics was haloperidol, with 1,268 users in 2006. Perphenazine and zuclopenthixol were among the least prescribed, with only 349 and 148 users, respectively, in 2006. Among the second-generation antipsychotics, risperidone was consistently the most commonly prescribed agent, with 9,570 users in 2006, while clozapine was the least prescribed, with only 479 users in 2006. Olanzapine and quetiapine were prescribed to 5,602 and 5,001 patients, respectively, in 2006. Prevalence of use for clozapine increased from .01% in 1996 to .04% in 2006, while for risperidone values increased from .07% to .81% in the same time interval. Olanzapine and quetiapine showed similar trends, with prevalence of use reaching .48% and .43%, respectively, in 2006.

Clozapine use was confined to the age groups of 19–35 and 36–65, with limited use among patients over 65 years and almost no use among patients younger than 18 years. The male-to-female ratio for clozapine users ranged from 2.2 to 3.0 in the 19–35 age group and from 1.4 to 2.2 in the 36–65 age group. For risperidone, the male-to-female ratio fluctuated between 1.5 to 3.7 in the 0–18 and 19–35 age groups, but it was close to 1.0 in the 36–65 age group and remained consistent through the years at .5 in the over 65 age group. These trends were similar to those observed for olanzapine (1.3 to 2.5 in the 0–18 age group and in the 19–35 age group). For quetiapine, the ratios were around 1.5 in the youth group (0–18 years), around 1.0 in the 19–35 age group, and less than 1.0 in the older groups.

Clozapine was prescribed by a limited number of physicians: between 40 and 220 unique prescribers per year were identified in the course of the decade. The highest number was observed for risperidone, with more than 700 unique prescribers in 2006.

Utilization of depot formulations appeared to have remained stable through the years, with a maximum of 1,318 users in 1998 and a minimum of 869 in 2004. The use of the most commonly prescribed depot formulation (fluphenazine decanoate) decreased from 471 users in 1996 to 297 users in 2006. There were 100 patients taking zuclopenthixol decanoate in 2006. The new long-acting formulation of risperidone was approved for marketing in Canada in July 2004; in 2006 a total of 19 patients were given prescriptions for this new product, which has been reimbursed by the Manitoba Provincial Drug Programs only by special authorization, thus limiting its use.

Diagnoses

Stratification of antipsychotic users by diagnosis showed that in the youth population (0–18 years), second-generation agents were mostly prescribed to patients with a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder ( ICD-9 314) and conduct disorders ( ICD-9 312). Risperidone showed the highest number of prescriptions, with more than 15,000 prescriptions written that were associated with users having a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in 2006 (a 100-fold increase since 1997). The use of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone was also linked to diagnoses of autism ( ICD-9 299) and mood disorders ( ICD-9 296); however, prescription numbers associated with these codes were much lower (approximately 3,000 prescriptions in 2006 for risperidone). Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among young antipsychotic users increased from 28% in 1996 to 66% in 2006; in the same time interval, prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the total youth population increased from .04% to .41%. The increases in prevalence of a conduct disorder diagnosis were similar but less pronounced—that is, from 29% to 43% among young antipsychotic users and from .04% to .27% in the total youth population. Autism was diagnosed among 12% of young antipsychotic users in 1996 and among 14% of young antipsychotic users in 2006, with a total prevalence increase from .02% to .09%. Prevalence of schizophrenia or related disorders ( ICD-9 295) in this age group was low, but it increased slightly from .013% in 1996 to .018% in 2006.

Schizophrenia was most prevalent in the 19–35 and 36–65 age groups. The proportion of antipsychotic users with a diagnosis of schizophrenia changed in the 19–35 age group from 65% in 1996 to 42% in 2006; in the 36–65 age group the proportion decreased from 63% to 58% between 1996 and 2006. Relative to the entire population, the overall yearly prevalence of schizophrenia among outpatients remained at approximately .6% during the time frame of the study. Nevertheless, the number of prescriptions for risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine associated with this indication increased significantly with time: in 2006, they had become the most prescribed agents, with more than 50,000 prescriptions for risperidone (a tenfold increase since 1996), approximately 49,000 for olanzapine, and more than 30,000 for quetiapine. The number of prescriptions for clozapine was lower at approximately 20,000.

In the elderly group (over 65 years), most prescriptions for the second-generation antipsychotics were associated with diagnoses of dementia ( ICD-9 290 and ICD-9 294) and Alzheimer's disease ( ICD-9 331), with more than 80,000 prescriptions for risperidone alone in 2006. Total prevalence of these diagnoses increased in this age group from 2.0% to 3.7% and .65% to 1.15%, respectively, between 1996 and 2006.

Total prevalence of mood disorders ( ICD-9 296) was less than 10% of all the diagnoses reported in the youth group (total prevalence increased from .01% to .09%) and less than 5% in the elderly group across the years (total prevalence increased from .65% to .82%); in the 19–35 and in the 36–65 age groups, values averaged at 15% to 16% (total prevalence increased from .08% to .14% in the 19–35 age group and from .13% to .24% in the 36–65 age group between 1996 and 2006).

Costs

Total annual expenditures for antipsychotics increased in Manitoba from $1.7 million in 1996 to $22 million in 2006 ( Table 2 ). The cost per resident and per patient, respectively, also increased from an average of $1.5 per year in 1996 to $18.7 in 2006 (1,147% increase), and from $119.90 per year in 1996 to $935.20 in 2006 (680% increase) ( Table 2 ). Total costs and costs relative to the acquisition of second- versus first-generation antipsychotics are reported in Figure 3 . The portion of total costs covered by the government-sponsored provincial drug program is also highlighted in Figure 3 .

The antipsychotic market share for the second-generation agents rose from 10% in 1996 to 80% in 2006, overtaking the market for first-generation agents in 2001. At that time the increase in total cost for antipsychotic pharmacotherapy exceeded the 500% mark.

Discussion

The administrative databases that have been maintained in Manitoba since the early 1980s, with the addition of Manitoba Health's Drug Program Information Network in 1995, allow a complete "real world" evaluation of utilization of health services in a population. The results are not affected by sampling errors or biased by restrictions based on insurance coverage. Prescription data are inclusive of all community residents of Manitoba, including seniors living in personal care homes.

Utilization patterns of antipsychotic agents have changed dramatically in Manitoba because of the introduction of the new agents starting in the early 1990s, with a significant increase in number of prescriptions and number of antipsychotic users between 1996 and 2006. By the year 2006, second-generation agents accounted for 80% of the market share for all antipsychotics.

This study demonstrates widespread use of second-generation antipsychotics across all age groups of the population. Although our data did not allow an unequivocal linkage to the reasons for prescribing, several observations confirmed that these agents are also used to control psychosis and aggressive behavior in conditions other than schizophrenia, particularly in the youth and in the elderly populations. Although some indications are not currently approved in Canada (only risperidone obtained federal approval in 1999 for behavioral disturbances in dementia), they have been supported by recent literature ( 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ) The cost of pharmaceuticals has increased dramatically in the past decade, and significant concerns have been expressed by all provinces in Canada on the sustainability of their drug programs. Cost containment strategies have been considered top priorities for provincial governments in recent times, and changes have occurred to the Manitoba Pharmacare deductibles over the past few years ( 27 ).

Schizophrenia prevalence was stable in Manitoba and the utilization of clozapine remained limited to the adult groups of patients, where the diagnosis of schizophrenia is most prevalent. Compared with the other second-generation antipsychotics, the use of clozapine was low but consistent with its indication for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Clozapine was prescribed by a limited number of prescribers, which suggest that its prescription might be linked more to specialists than to general practitioners. Overall, young males represented the fastest-growing group of users of second-generation antipsychotics, with an increase that was almost threefold the increase observed in the adult groups. The most prescribed antipsychotic was risperidone.

The cost of pharmaceuticals has increased dramatically in the past decade, and significant concerns have been expressed by all provinces in Canada on the sustainability of their drug programs. Cost containment strategies have been considered top priorities for provincial governments in recent times, and changes have occurred to the Manitoba Pharmacare deductibles over the past few years ( 28 ). Recently, an installment payment option for low-income individuals has been introduced to facilitate deductible payments ( 29 ).

Antipsychotic pharmacotherapies have been reimbursed through the years by the Manitoba provincial drug programs, and the second-generation antipsychotics were listed upon federal approval as unrestricted benefits on the Manitoba Drug Benefits and Interchangeability Formulary ( 30 ).

Over the past decade the government-sponsored drug plans appear to have covered most of the costs for all antipsychotic medications in Manitoba: in 1998 the expenditures for antipsychotic agents were approximately 1.7% of the total budget, while in 2003 values had reached 6.5% of the total budget of $217.7 million ( 31 ). With a projected budget of $280.4 million for 2006, the percentage spent for antipsychotic medications would have remained at 6.6%.

Conclusions

This is the first comprehensive report on the use of antipsychotic agents in the complete population of a Canadian province. A dramatic increase in use of the second-generation agents in the past decade, particularly in the male youth population, has been observed. By 2006 newer agents had taken over 80% of the total market share of antipsychotics. The percentage of the provincial government drug budget spent on antipsychotic medications increased from 1.7% in 1996 to an estimated 6.6% in 2006. Further analysis is warranted to determine whether the use of these medications has produced a cost-effective improvement in the treatment of patients living with mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant MMSF 2006-G0080627 from the Manitoba Medical Service Foundation. The authors thank Charles Burchill, M.Sc., for his insightful assistance in retrieving the data. The results and conclusions presented are those of the authors. No official endorsement by Manitoba Health is intended or should be inferred.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Kane J, Honingfeld G, Singer J, et al: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:789–796, 1988Google Scholar

2. Essock SM, Hargreaves WA, Covell NH, et al: Clozapine's effectiveness for patients in state hospitals: results from a randomized study. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 32: 683–697, 1996Google Scholar

3. Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Abraham D, et al: Efficacy and extrapyramidal side-effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophrenia Research 35:51–68, 1999Google Scholar

4. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM: Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:414–425, 2004Google Scholar

5. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia: 2nd ed. American Journal of Psychiatry 161(Feb suppl): 1–56, 2004Google Scholar

6. Addington D, Bouchard RH, Goldberg J, et al: Clinical practice guidelines: treatment of schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50(suppl 1):2S, 2005Google Scholar

7. Yathman LN, Kennedy SH, O'Donovan C, et al: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatment (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disorders 8:721–739, 2006Google Scholar

8. Rosenheck R, Perlick D, Bingham S, et al: Effectiveness and cost of olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290:2693–2702, 2003Google Scholar

9. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al: Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 353:1209–1223, 2005Google Scholar

10. Gardner DM, Baldessarini RJ, Waraich P: Modern antipsychotic drugs: a critical overview. Canadian Medical Association Journal 172:1703–1711, 2005Google Scholar

11. Hanrahan P, Luchins DJ, Fabian R, et al: Cost-effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications versus conventional medication. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 7:1749–1758, 2006Google Scholar

12. Polsky D, Doshi J, Bauer M, et al: Clinical trial-based cost-effectiveness analyses of antipsychotic use. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:2017–2047, 2006Google Scholar

13. Wheeler A: Atypical antipsychotic use for adult outpatients in New Zealand's Auckland and Northland regions. New Zealand Medical Journal 119(1237):U2055, 2006Google Scholar

14. Rapoport M, Mamdani M, Shulman KI, et al: Antipsychotic use in the elderly: shifting trends and increasing costs. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 20:749–753, 2005Google Scholar

15. Mamdani M, Rapoport M, Shulman KI, et al: Mental health–related drug utilization among older adults: prevalence, trends and costs. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13:892–900, 2005Google Scholar

16. Aparasu RR, Bhatara V, Gupta S: US national trends in the use of antipsychotics during office visits, 1998–2002. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 17:147–152, 2005Google Scholar

17. Trifir=G, Spina E, Brignoli O, et al: Antipsychotic prescribing pattern among Italian general practitioners: a population-based study during the years 1999–2002. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 61:47–53, 2005Google Scholar

18. Ganguly R, Kotzan JA, Miller LS, et al: Prevalence, trends and factors associated with antipsychotic Medicaid-eligible schizophrenia patients, 1998–2000. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:1377–1388, 2004Google Scholar

19. Rochon PA, Stukel TA, Bronskill SE, et al: Variation in nursing home prescribing rates. Archives of Internal Medicine 167:676–683, 2007Google Scholar

20. Kogut SJ, Yam F, Dufresne R: Prescribing of antipsychotic medication in a Medicaid population: use of polytherapy and off-label dosages. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 11:17–24, 2005Google Scholar

21. Kozyrskyj A, Mustard, D: Validation of an electronic, population based prescription database. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 32: 1152–1157, 1998Google Scholar

22. Percudani MM, Barbui C, Fortino I, et al: Antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs prescribing in Lombardy [in Italian]. Epidemiologia Psychiatrica 15:59–70, 2006Google Scholar

23. Stachnik JM, Nunn-Thompson C: Use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of autistic disorder. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 41:626–634, 2007Google Scholar

24. Aras S, Tas FV, Unlu G: Medication prescribing practices in a child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic. Child: Care, Health and Development 33:482–490, 2007Google Scholar

25. Sareen J, Kirshner A, Lander M, et al: Do antipsychotics ameliorate or exacerbate obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms? A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders 82:167–174, 2004Google Scholar

26. Recupero PR, Rainey SE: Managing risk when considering the use of atypical antipsychotics for elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 13:143–152, 2007Google Scholar

27. Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al: Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer's disease. New England Journal of Medicine 355: 1525–1538, 2006Google Scholar

28. Pharmacare: a program for today and tomorrow. News release. Winnipeg, Canada, Manitoba Health, 2006. Available at www.gov.mb.ca/health/pharmacare/strategy.htmlGoogle Scholar

29. New program allows Pharmacare drug deductibles to be paid in monthly installments. News release. Winnipeg, Canada, Manitoba Health, 2006. Available at www.gov.mb.ca/chc/press/top/2006/05/2006-05-10-03.htmlGoogle Scholar

30. Manitoba Drug Benefits and Interchangeability Formulary. Winnipeg, Canada, Manitoba Health. Available at www.gov.mb.ca/health/mdbif/bulletins.htmlGoogle Scholar

31. Drug Expenditures in Canada, 1985 to 2006. Ottawa, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2006. Available at secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cwpage=AR80E&cwtopic=80Google Scholar