Rates and Risk Factors by Ethnic Group for Suicides Within a Year of Contact With Mental Health Services in England and Wales

A million people worldwide die from suicide each year ( 1 ). Prevention of suicide is considered an important public health issue. Strategies target high-risk groups and rely on the identification of modifiable factors ( 2 ) based on good contemporary data. One group at high risk is composed of people who have been in contact with mental health services. They are the target of suicide prevention strategies in many countries, because they are considered to be accessible and because changes in clinical assessment and practice are considered possible effective interventions.

In international studies, specific ethnic groups are shown to be at high risk of suicide ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ). Therefore, in multicultural countries suicide prevention strategies need to address variation in risk by ethnicity and the possible modifiable causes. Trends in suicide by ethnicity may reflect differences in exposure to known socioeconomic risk factors or issues more specific to minority groups, such as migration, resettlement, social exclusion, and poorer access to health care ( 3 ). In England 9% of the population and 21% of psychiatric inpatients are from minority ethnic groups ( 12 , 13 ). Higher rates of service use among specific minority ethnic groups may indicate a higher rate of mental illness, which in turn indicates a higher risk of suicide ( 4 , 5 , 6 ).

In the United States, Puerto Ricans and Mexican Americans have lower suicide rates, compared with whites ( 7 ). Although Hispanics have a suicide rate lower than the U.S. national rate, suicide was the third leading cause of death among Hispanic youths aged 10 to 24 years ( 8 ). African Americans also have lower suicide rates than white Americans ( 4 ). There is a high rate of suicide among people originating from the Indian subcontinent, irrespective of where in the world they settle ( 9 ). Compared with a white British reference group, a higher suicide rate has been reported among Indian- and East-African- born women ( 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 ). Data from the United Kingdom show rising rates of suicide among young men born in the Caribbean ( 11 ) and a relatively higher risk of suicide among younger, as opposed to older, black Caribbean men with psychosis ( 3 ).

Preventive actions that diminish access to methods of suicide are known to reduce the risk of suicide across ethnic groups ( 16 , 17 , 18 ). Orthodox religious practices are more common among recent immigrants in the United Kingdom and the United States and may act as a protective factor ( 19 , 20 ). In England and Wales, the National Confidential Inquiry (NCI) records suicides among people in contact with services in the preceding 12 months ( 21 , 22 ). The NCI previously reported that 6% of all patient suicides from April 1, 1996, to March 30, 2000, were from an ethnic minority group ( 22 ). The NCI also found that the most common method of suicide in ethnic minority groups was hanging, that violent methods were more common among persons from ethnic minority groups than among white persons, and that schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis, especially among black Caribbean patients who also had high rates of unemployment, previous violence, and drug abuse. Young people who have been recently discharged from mental health facilities and inpatients may also be high risk groups ( 20 , 21 , 22 ).

The first objective of the national suicide prevention strategy is to "Reduce the number of suicides by people who are currently or have recently been in contact with mental health services" ( 21 , 22 ). Because persons from ethnic minority groups are high users of mental health services, for this objective to be met, data are needed on differential suicide rates and risk factors to see whether general preventive strategies ( 16 , 17 , 18 ) or specific preventive strategies for specific ethnic groups are needed ( 18 , 19 , 20 ).

Data on people who commit suicide in England and Wales after contact with mental health services in the previous year are collected with the NCI ( 21 , 22 ). We used these data in our study to extend existing knowledge about ethnicity and suicide ( 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 20 , 22 ). Our study had three aims. First, this study aimed to estimate the rate of suicide in ethnic minority groups. Second, given the existing literature of elevated suicide rates among young people, especially women, born in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh and increasing rates of suicide among young people, especially men, of Caribbean origin ( 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 ), we tested the hypothesis that rates of suicide were higher among young women from South-Asian ethnic groups and young black men from the Caribbean and looked at both genders to see whether the risks associated with specific age and gender groups differed. And third, so there is a basis for suicide prevention strategies, we tested the hypothesis that there are ethnic differences in the presence of factors that are used in the assessment of suicidal risk.

Methods

Data source

The NCI receives data on all deaths that are potentially classifiable as suicides from the United Kingdom's Office for National Statistics and ascertains whether the people who committed suicide had been in contact with mental health services in England and Wales in the 12 months before the completed suicide ( 22 ). For those who had been in contact with services, the NCI then seeks more in-depth information from the lead clinician of the team who last saw them. The lead clinician completes a questionnaire about the suicide victim. Because this is a statutory requirement, completion rates have been high (average of 97%). These data provide a rich source of information about the last contact with services, the suicidal act, the mental state of the individual, the circumstances of that suicide, whether it was preventable, and what may have prevented it.

All analyses were based on the period January 1, 1996, to December 31, 2001. We restricted the analyses to this five-year period because numerators before 1996 and after 2001 were incomplete at the time this study was conducted in 2005 and 2006.

Defining suicide

Open verdicts and verdicts of death from undetermined causes are often reached in cases of suicide, and these are conventionally included in official statistics ( 21 , 22 ). We used a broad definition of suicide for analyses and included anyone whom the coroner rated as a suicide victim ( 19 , 21 , 22 ).

Defining ethnicity

The lead clinician who completed the NCI form was asked to report the ethnicity of the patient using the Office for National Statistics categories: South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladesh), black Caribbean, black African, white, Chinese, mixed, or other.

For analyses we included four groups: black Caribbean, black African, South Asian, and white. These reflect the largest ethnic groups in England and Wales and are categories that are used in the national census and in national research. The numbers of actual suicides for the ethnic groups other than those listed above were small (N=14), and meaningful conclusions could not be drawn from those groups. The second largest ethnic group in England and Wales, the Irish, did not have data collected separately, so we were unable to investigate it.

Descriptive data

From the inquiry returns we captured age, gender, employment status, marital status, primary diagnosis, time between last service contact and suicide, and method of suicide. Methods of suicide across ethnic groups had previously been reported for four of the five years of data that we were using ( 22 ); our analyses showed no differences between our data and the published four-year analyses ( 22 ). Therefore, we do not report on methods of suicide in this article.

Suicide rates

We calculated suicide rates using data from the NCI as the numerator and data from the 1991 and 2001 national census as the denominator. The denominators for the years 1996 to 2001 were estimated from ethnic-specific age, sex, and age-by-sex population projections. Suicide rates per 100,000 person-years and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each ethnic group, and then the rates were calculated by sex and age within each ethnic group. We report rates for three age groups, 13 to 24 years, 25 to 39 years, and 40 years and older. The age groups used reflect those collated by the NCI and permit investigation of risk factors and rates among adolescents and young adults, groups in which the risk of suicide is reported to be rising.

Perceived preventability and clinical risk factors

A comparison between ethnic groups was made for the symptoms considered to increase the risk of suicide: suicidal ideas, delusions and hallucinations, depressive symptoms, deliberate self-harm, emotional distress, hopelessness, and hostility. We also compared judgments about suicide risk by staff as a dichotomous variable: none or some risk. Some risk was an aggregated category of the original categories of low, moderate, and high risk. We also compared clinicians' ratings of the preventability of suicide: an answer of yes or no to the question, "in your opinion could the suicide have been prevented?"

Statistical analyses

For comparison of demographic information and risk factors across ethnic groups, we used nonparametric chi square tests for overall differences and report the actual numbers and percentages. Rates, standardized mortality ratios (SMRs), and corresponding CIs were calculated by using Confidence Interval Analysis software (www.som.soton.ac.uk/cia). We used the white group as the reference group, because this was the largest ethnic group with the most events and therefore provides the most stable estimates of rates by indirect standardization. In subgroup analysis the white counterparts of the same age and gender group were the reference group. Finally, to compare risk factors across ethnic groups with different demographic and diagnostic profiles, we built logistic regression models adjusted for age, gender, and diagnosis. The results are reported as odds ratios and CIs.

The study received full ethical approval from a national multicenter research ethics committee in Cardiff, Wales.

Results

Sample characteristics

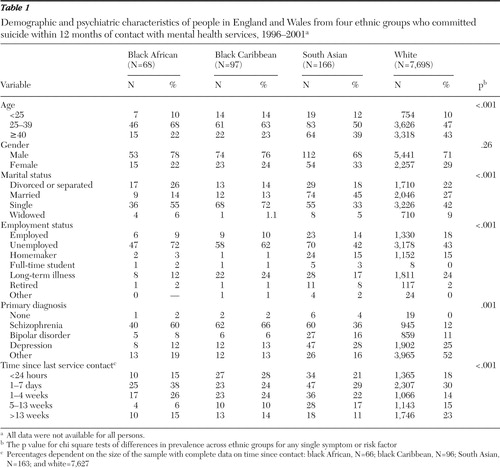

There were significant differences in the sociodemographic characteristics between groups. These differences reflect the younger age of ethnic minority populations, their increased risk of unemployment, and their differences in rates of marriage, which have also been shown in other studies ( 22 ) ( Table 1 ). Schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis among black Africans and black Caribbeans. Suicide within 24 hours of professional contact was most often reported among black Caribbeans, and suicide within one to seven days of contact was most commonly found among black Africans.

|

Rates of suicide

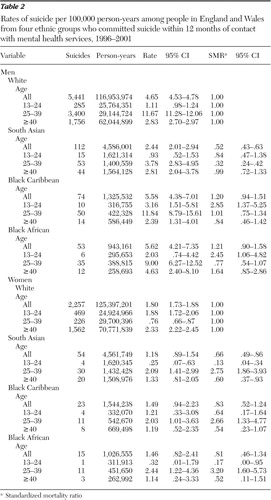

A total of 8,029 people in the four groups committed suicide within 12 months of contact with services during the five-year study period: 5,441 of the suicides were of white men, and 239 were of men from the three other ethnic groups; 2,257 of the suicides were of white women and 92 were of women from the three other ethnic groups ( Table 2 ).

|

Rate of suicide in ethnic minority groups. The overall SMRs were significantly lower for the South-Asian group, compared with the white reference group; however, the SMRs for either the black Caribbean or black African groups did not indicate significantly different suicide rates from the white group.

Examining rates by gender and age group. We tested the hypothesis that rates of suicide would be higher among young black Caribbean men and young South-Asian women. When the analyses were stratified by gender and age group, a high SMR was found among black Caribbean and black African men aged between 13 and 24. A low SMR was found among South-Asian and black African women aged between 13 and 24 and South-Asian women aged 40 or older. However, among women aged 25–39, South-Asian, black Caribbean, and black African women had high SMRs ( Table 2 ).

Clinical indicators of risk

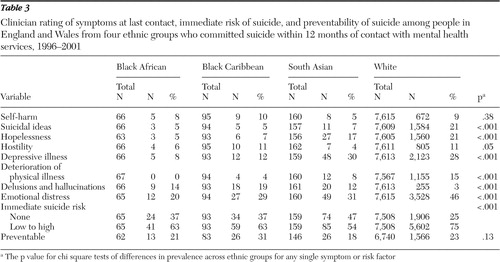

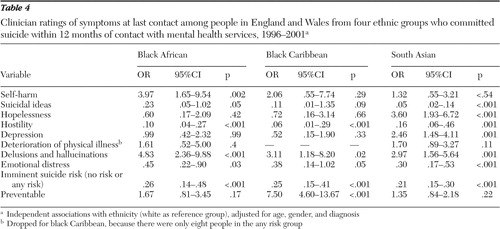

We also tested the hypothesis that there would be ethnic differences in the presence of factors that are used in the assessment of suicidal risk. Clinical indicators of risk showed ethnic variations in unadjusted analyses and in regression models adjusted for age, gender, and diagnosis. All comparisons were with white people completing suicide. Suicidal ideas, emotional distress, and hostility were less common among black Africans, black Caribbeans, and South Asians ( Tables 3 and 4 ). Hopelessness and depression were more common among South Asians. Delusions and hallucinations were more common among black Africans, black Caribbeans, and South Asians ( Tables 3 and 4 ). Self-harm was significantly more common among black Africans ( Table 4 ). The perceived level of immediate risk of suicide was highest among whites ( Tables 3 and 4 ).

|

|

Preventability. Clinicians reported that suicide was preventable for 31% of black Caribbeans who committed suicide and 18% of South Asians who committed suicide. In adjusted logistic regression analyses, clinicians' ratings of preventable suicide were most commonly found among black Caribbeans who committed suicide, compared with whites who committed suicide ( Table 4 ). There were no significant differences in ratings of preventability between whites who committed suicide and black Africans or South Asians who committed suicide.

Discussion

We did not find general ethnic group differences, but we did find variations in rates of suicide by age, gender, and ethnic group. Our study found high rates of suicide among black African and black Caribbean men aged 13–24 living in England and Wales. These findings were similar to those in U.S. studies that found similar trends among African-American and Hispanic youths ( 15 , 23 , 24 ). Although U.K. and U.S. ethnic minority groups have different cultural and social contexts and histories of migration, they do share experiences of social exclusion and greater unemployment that may contribute to the risks for mental disorders. There are also similarities in the pattern of interaction and experiences of mental health services of these ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom and the United States ( 4 , 25 ). It may be useful to create policies that aim to improve the interaction between mental health services and black and other ethnic minority groups in order to deliver better clinical outcomes ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 6 , 25 ).

The lower risk of suicide among young South-Asian women requires explanation, because this finding contrasts with the picture of mental illness and suicide from community settings and population studies ( 5 , 6 , 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 ). First, the high rate of reported suicide among South Asians is based mainly on studies that defined ethnic group on the basis of place of birth. Also, these data are over a decade old. The South-Asian group in our sample was mostly born in the United Kingdom. It may be that this group has a lower rate of suicide than older age groups that were born in India, Pakistan, or Bangladesh. Second, it is known that people of South-Asian origin seek help from primary care but are less likely to be referred into secondary care services, even if mental disorders are detected ( 5 ). Thus there may be selection bias in the sample, in that only those in contact with mental health services are included in the NCI data.

We were not able to determine rates in subgroups of South Asians because of the coding of ethnic categories in the NCI. However, it is conceivable that a higher rate among Indian people ( 9 ) is concealed by a lower rate among Pakistani and Bangladeshi Muslim people ( 15 ). Similarly, the white group may contain minority groups—such as the Irish, who have high reported suicide rates and high contact with services—and other subcultural groups that cannot be separated out for analyses ( 6 ).

Underenumeration of denominators is greatest among young men and is often proposed to explain overestimates of illness rates among young men ( 26 , 27 ). However, levels of underenumeration were accounted for in the 2001 census and still cannot explain the 250% to 290% higher risk of suicide among black Caribbeans and black Africans aged 13 to 24 years.

Almost one-third of suicides in the black Caribbean group were considered by treating clinicians to have been preventable; this finding was sustained despite adjustment for diagnosis. The data on symptoms at the suicide victims' last contact with services suggest that some ethnic groups have more delusions and hallucination and fewer symptoms indicative of suicide risk. Emotional distress, depressive symptoms, hopelessness, hostility, and imminent risk of suicide were less common in ethnic minority groups. This may suggest clinician bias in the recognition of emotional symptoms and signs of psychosis or in responding to these symptoms in ethnic groups. Psychiatric practice is often criticized for being ethnocentric and pathologizing culturally appropriate expressions of distress, but rarely are omissions in the assessment of symptoms reported. These findings may also reflect ethnic differences in the quality and quantity of expressions of distress and the shaping of symptoms by cultural idioms of distress ( 4 , 28 , 29 , 30 ). Irrespective of the reasons for these variations, the absence of obvious depressive and suicidal indicators alongside the presence of delusions and hallucinations may, according to our data, together suggest a higher suicide risk as a result of an active and undertreated psychosis ( 18 ). The lower prevalence of obvious suicidal indicators in ethnic minority groups may mislead clinicians into underestimating the suicide risk.

Alternatively, the data may suggest treatment resistance, noncompliance, or ineffective recognition and treatment of an affective psychosis ( 29 , 30 ). Other explanations of the findings of prominent symptoms and a higher risk of suicide among ethnic minority groups are conflict with clinical teams, less satisfaction with services, and consequently poorer take up of effective interventions ( 31 , 32 ). The regression models showing suicidal and risk symptom variations by ethnic group were adjusted for age and gender; we did not discern whether there were ethnic-group-specific age and gender variations, because such analyses would have little power to detect differences between age, gender, and ethnic-group strata and because the findings could not easily be translated into clinical practice.

Conclusions

As a first study and a secondary data analysis there are a number of questions left unanswered, but this study can offer advice for future research. The black African and black Caribbean groups were characterized by high rates of delusions and hallucinations and previous deliberate self-harm but low rates of other clinical indicators of suicide at their last contact. Of note, suicidal ideas and depression were less likely to be reported in these two groups. Members of the South-Asian group who committed suicide had high levels of hopelessness, psychotic symptoms, and depression but low levels of suicidal ideation, compared with the white group. It would seem that there are different balances of risk factors for different ethnic groups. The weight of different symptoms in the clinical prediction of suicide risk may therefore be different for different groups. Awareness of this fact is important for clinicians, as is awareness of the high suicide rates in some ethnic groups.

The differences in suicide risk by age and sex may be important for strategy. Efforts could be directed at targeting prevention toward young people in contact with mental health services and by developing culturally appropriate and effective strategies to assess the risk of suicide among ethnic minority groups and to engage these groups in treatment. Specific groups at risk include black Caribbean and black African men aged 13–24, black Caribbean and black African women aged 25–39, and South-Asian women aged 25–39. Qualitative studies of women aged 25–39 may help unearth other currently unknown risk factors.

Future research will also need to investigate ethnic subgroups—for instance South-Asian subgroups and African subgroups. In the South-Asian group, young women and those not in contact with services should get specific attention in order to evaluate whether rates of suicide are actually decreasing in this group or whether there is a selection bias in our sample. It is important not to forget how little we know about white subgroups, such as the Irish, although some research does indicate that they have high rates of suicide and depression ( 6 ).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health in England. Farhat Rasul, Ph.D., was research fellow to the project and gathered preliminary data. The authors thank the steering group chaired by David Gunnell, M.D., Ch.B., and members of the group.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Bertolote JM: Figures and Facts About Suicide. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1999Google Scholar

2. Bhugra D, Mastrogianni A: Globalisation and mental disorders: overview with relation to depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 184:10–20, 2004Google Scholar

3. McKenzie K, van Os J, Samele C, et al: Suicide and attempted suicide among people of Caribbean origin with psychosis living in the UK. British Journal of Psychiatry 183: 40–44, 2003Google Scholar

4. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

5. Bhui K, Stansfeld S, Hull S, et al: Ethnic variations in pathways to and use of specialist mental health services in the UK: systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry 182:105–116, 2003Google Scholar

6. Inside Outside: Improving Mental Health Services for Black and Minority Ethnic Communities in England. London, National Institute of Mental Health in England, 2003. Available at www.dh.gov.uk/prodcon sumdh/groups/dhdigitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh4019452.pdfGoogle Scholar

7. Oquendo MA, Ellis SP, Greenwald S, et al: Ethnic and sex differences in suicide rates relative to major depression in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 158: 1652–1658, 2001Google Scholar

8. Methods of suicide among persons aged 10–19 years—United States, 1992–2001. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Reports 53: 471–474, 2004Google Scholar

9. Patel SP, Gaw AC: Suicide among immigrants from the Indian subcontinent: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:517–521, 1996Google Scholar

10. Soni Raleigh V, Bulusu L, Balarajan R: Suicides among immigrants from the Indian subcontinent. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:46–50, 1990Google Scholar

11. Soni Raleigh V, Balarajan R: Suicide and self-burning among Indians and West Indians in England and Wales. British Journal of Psychiatry 161:365–368, 1992Google Scholar

12. Census shows large rise in UK ethnic population. Society Guardian. Feb 13, 2003 Available at www.guardian.co.uk/society/2003/feb/13/britishidentityandsociety.uknewsGoogle Scholar

13. Count Me In: Results of a National Census of Inpatients in Mental Health Hospitals and Facilities in England and Wales. Bunhill Row, London, Care Services Improvement Partnership, National Institute for Mental Health in England, Healthcare Commission, Nov 2005. Available at www. mhac.org.uk/census2006/docs/FINALweb pdfcensusreport5th1-0.pdfGoogle Scholar

14. Soni Raleigh V: Suicide levels and trends among immigrants in England and Wales. Health Trends 24:91–94, 1996Google Scholar

15. Soni Raleigh V: Suicide patterns and trends in people of Indian Subcontinent and Caribbean origin in England and Wales. Ethnicity and Health 1:55–63, 1996Google Scholar

16. Goldney RD: A global view of suicidal behaviour. Emergency Medicine (Fremantle) 14:24–34, 2002Google Scholar

17. Levi F, La Vecchia C, Saraceno B: Global suicide rates. European Journal of Public Health 13:97–98, 2003Google Scholar

18. Piper TM, Tracy M, Bucciarelli A, et al: Firearm suicide in New York City in the 1990s. Injuries Prevention 12:41–45, 2006Google Scholar

19. Neeleman J, Wessely S, Lewis G: Suicide acceptability in African- and White Americans: the role of religion. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 186:12–16, 1998Google Scholar

20. McKenzie K, Samele C, Van Horn E, et al: Comparison of the outcome and treatment of psychosis in people of Caribbean origin living in the UK and British Whites: report from the UK700 trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 178:160–165, 2001Google Scholar

21. Meehan J, Kapur N, Hunt IM, et al: Suicide in mental health in-patients and within 3 months of discharge: national clinical survey. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:129–134, 2006Google Scholar

22. Hunt IM, Kapur N, Robinson J, et al: Suicide within 12 months of mental health service contact in different age and diagnostic groups: national clinical survey. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:135–142, 2006Google Scholar

23. Griffith EE, Bell C: Recent trends in suicide and homicide among blacks. JAMA 262:271–272, 1989Google Scholar

24. Stack S: Culture and suicide among African Americans. Transcultural Psychiatry 35: 253–269, 1998Google Scholar

25. Bhui K, Christie Y, Bhugra D: The essential elements of culturally sensitive psychiatric services. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 41:242–256, 1995Google Scholar

26. Leese M, Loftus L, Thornicroft G: Adjusting for underenumeration in the 1991 census. British Medical Journal 311:394, 1995Google Scholar

27. Majeed FA, Cook DG, Poloniecki J, et al: Using data from the 1991 census. British Medical Journal 310:1511–1514, 1995Google Scholar

28. Suhail K, Cochrane R: Effect of culture and environment on the phenomenology of delusions and hallucinations. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 48:126–138, 2002Google Scholar

29. Johns LC, Nazroo JY, Bebbington P, et al: Occurrence of hallucinatory experiences in a community sample and ethnic variations. British Journal of Psychiatry 180:174–178, 2002Google Scholar

30. Strakowski SM, Keck PE Jr, Arnold LM, et al: Ethnicity and diagnosis in patients with affective disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:747–754, 2003Google Scholar

31. De Hert M, McKenzie K, Peuskens J: Risk factors for suicide in young people suffering from schizophrenia: a long-term follow-up study. Schizophrenia Research 47:127–134, 2001Google Scholar

32. Parkman S, Davies S, Leese M, et al: Ethnic differences in satisfaction with mental health services among representative people with psychosis in south London: PRiSM study 4. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:260–264, 1997Google Scholar