Perpetration of Violence, Violent Victimization, and Severe Mental Illness: Balancing Public Health Concerns

For decades, researchers have investigated violence perpetrated by persons with severe mental illness ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). This research has, in part, been driven by a common perception that persons with mental illness are dangerous ( 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ). Far fewer empirical studies have examined the risk of violent victimization among persons with severe mental illness ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ), and to our knowledge no comprehensive literature review has been published. Moreover, no literature review has weighed the relative importance of violence perpetration and violent victimization among persons with severe mental illness.

Reviewing the literature on perpetration and victimization is timely. In the United States, severe mental illness is estimated to affect one in 17 persons, or 6% of adults (13.2 million people) ( 21 ). Long-term psychiatric hospitalizations are now rare; the median length of stay has been reduced from 41 days in 1971 to 5.4 days in 1997 ( 22 ). Consequently, more persons with severe mental illness now live in the community. Moreover, the recent homicides in Omaha and at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) have highlighted the importance of examining the role of mental illness in the perpetration of violence.

In this article, we review empirical studies conducted in the United States and published since 1990 of violence perpetration and violent victimization among persons with severe mental illness. We also weigh the relative importance—as public health concerns—of violence perpetration and violent victimization among persons with severe mental illness. Finally, we suggest directions for future research and discuss the implications of our conclusions for treatment and public health policy.

Methods

Definitions

Severe mental illness refers to a subset of psychiatric disorders—psychotic disorders and major affective disorders—that are characterized by severe and persistent cognitive, behavioral, and emotional symptoms that reduce daily functioning. Despite medication and other treatment, symptoms periodically worsen such that short-term hospitalization is required ( 21 ).

Procedures

All searches, restricted to studies conducted in the United States, were performed with three commonly used computerized bibliographic databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Studies were reviewed only if they were published empirical investigations of recent (past three years) prevalence or incidence of violence perpetration or violent victimization. We included studies of persons in treatment for severe mental illness; studies of special populations (for example, homeless persons) if separate rates were reported for persons with severe mental illness; and studies of nontreatment (community) samples if investigators compared persons with and without severe mental illness.

Two main searches—for perpetration of violence and violent victimization among persons with severe mental illness—were conducted with the following keywords: for violence perpetration, severe mental illness, mental illness, mental disorder, psychiatric disorder, psychopathology, violence, violent behavior, and violent act or acts; for violent victimization, severe mental illness, mental illness, mental disorder, psychiatric disorder, psychopathology, and victimization. Violent victimization includes rape and sexual assault, robbery, and physical assault ( 23 ).

Results

Violence perpetrated by persons with severe mental illness

Incidence. Incidence refers to the number of new cases of a disease that occur during a specifiedperiod of time in a population at risk of developing the disease ( 24 ). We could not find any studies that measured the incidence of violence perpetration.

Prevalence. Prevalence refers to the number of affected persons present in the population divided by the number of persons in the population within a given period of time ( 24 ). Table 1 lists studies of the prevalence of violence perpetration by the type of sample.

|

Outpatients.Table 1 lists four studies that examined outpatients ( 11 , 12 , 25 , 26 ). One study used a sample that was too small (N=42) to generate reliable prevalence rates ( 26 ). Prevalence of violence ranged from 2.3% ( 11 ) to 13.0% ( 25 ) and varied by time frame (recall period) and type of measure. The rates in the study by Brekke and colleagues ( 11 ) were lower than those in the other studies because of Brekke and colleagues' narrow definition of violence—criminal charges for a violent crime in the past three years (2.3%) and contacts with police for aggression against others (6.4%). Conversely, the rates in the study by Bartels and colleagues ( 25 ) were higher than those in other studies, most likely because these authors examined self-reported violence among "the most severely disturbed patients" discharged from a state hospital.

Psychiatric emergency room patients. As Table 1 shows, two studies examined psychiatric emergency room patients. Prevalence of violence ranged from 10.0% in the two weeks before patients' emergency room visits ( 27 ) to 36.0% in the previous three months ( 28 ). McNiel and Binder's ( 27 ) rates may be low because they used mental health records to assess violence instead of self-report. Conversely, Gondolf and colleagues ( 28 ), who studied an "accidental" sample (N=389), may have found higher rates because they used both self-reports and hospital records.

Inpatients.Table 1 shows that of the 31 published articles on violence perpetration among persons with severe mental illness, approximately half (48%, or 15 studies) ( 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ) examined samples composed solely of inpatients. Of these, more than half (53%, or eight studies) ( 29 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 41 ) included committed inpatients in the sample—four studies examined only committed inpatients ( 29 , 34 , 35 , 41 ). Prevalence rates varied widely in these studies, depending on the measure of violence and when the violence took place relative to the hospitalization.

For violence occurring before hospitalization, findings varied by time frame and by type of hospitalization. Prevalence ranged from 14.2% among voluntary inpatients in the month before hospitalization ( 43 ) to 50.4% among committed inpatients in the four months before hospitalization ( 41 ). The higher rates of violence among committed inpatients than among other inpatients may be the result of the national dangerousness standard used in many states' commitment procedures, in which being "imminently" or "probably" dangerous precipitates hospitalization ( 44 ). Overall, the prevalence of violence was highest in studies of committed inpatients, those that used broader definitions of violent behavior ( 35 , 41 ), and those that measured self-reported violence ( 35 , 41 ) instead of using medical chart reviews ( 29 , 40 ) or official records (medical records, police records, or civil commitment forms) ( 31 ).

For violence occurring during hospitalization, prevalence rates varied from 16.0% during the first week of hospitalization to 23.0% for violence occurring any time during hospitalization. Table 1 shows that all four studies of violence during hospitalization examined patients in locked units and assessed violence by using medical chart reviews ( 29 , 32 , 33 , 34 ).

For violence after hospitalization, findings varied by type of sample and time frame. The lowest prevalence rates of self-reported "physical violence" (3.7%) were reported within two weeks after discharge by voluntary inpatients ( 42 ). The highest rates (27.5%) were reported among inpatients participating in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study during the year after discharge, of whom over two-fifths had been involuntarily committed ( 39 ). Involuntary patients were significantly more likely to be violent at follow-up than voluntary patients ( 45 ). Table 1 shows that the prevalence of violence in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study decreased with time. Of note, after the analyses controlled for substance abuse, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of violence between the MacArthur sample of discharged patients and a control group of persons without mental disorders who lived in the community ( 39 ).

In summary, studies of inpatients with severe mental illness show that perpetration of violence is most prevalent among committed patients before hospitalization, when violence may have precipitated their commitment. Moreover, prevalence rates were higher in studies that assessed a broad range of self-reported violent acts than in those that relied solely on medical chart reviews.

Studies combining inpatients and outpatients. Six studies combined inpatients and outpatients. All collected self-reported data, and time frames varied from the past six months ( 46 , 47 ) to the past 18 months ( 48 ). Prevalence rates of violence ranged from 12.3% to 26.0% ( 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ), lower than prevalence rates found in most studies of inpatients and higher than rates found in most studies of outpatients. The highest rate (26.0%), which was reported by Elbogen and colleagues ( 49 ), combined self-reported violent behavior and any arrest (violent and nonviolent), which may have inflated the rates in this study.

Community samples. As Table 1 shows, only four of the 31 articles reported studies in which community samples were examined ( 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ). In the four articles, data were from two multisite community surveys of mental disorders—the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey ( 53 , 54 , 55 ) and the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) ( 52 ). Because these surveys were not designed to assess violent behavior, the authors derived a dichotomous variable—any violence (yes or no)—from the sections on mental disorders, physical health, and recent life events.

In studies that used the ECA data ( 53 , 54 , 55 ), the authors used five questions from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule's antisocial personality disorder and alcohol use disorder modules; respondents were scored as violent if they responded positively to one or more items. Items varied in the level of severity assessed from "physical fighting while drinking" to "used weapon in a fight." Among persons with severe mental illness, prevalence of any violent behavior in the past year ranged from 6.8% to 8.3% ( 53 , 54 , 55 )—up to four times higher than among persons who were not diagnosed as having a mental disorder. Swanson and colleagues ( 54 , 55 ) also examined differences by age, gender, and socioeconomic status in comparisons of persons with major mental disorders and persons without any disorder; however, subsamples were too small to estimate the effect of major mental disorder separately within sociodemographic categories ( 56 ).

In the study using NCS data ( 52 ), respondents were scored as violent if they reported that they "had serious trouble with the police or the law" or "had been in a physical fight." Analyses focused on differences among diagnostic groups. Prevalence of violence ranged from 4.6% in the past year for persons with a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder to 16.0% for persons with a past-year diagnosis of bipolar disorder; these rates were two to eight times higher than the prevalence among persons without a mental disorder. Findings from this study, however, conflated violent behavior with involvement with the police, which may or may not have been precipitated by violence.

Violent victimization among persons with severe mental illness

Incidence. Most general population studies of crime victimization, such as the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) ( 23 ), examine incidence. To our knowledge, only one study of adults in treatment with severe mental illness investigated the incidence of recent violent victimization ( 19 ). Using the same instruments as the NCVS, Teplin and colleagues ( 19 ) examined 936 randomly selected persons with severe mental illness from a random sample of treatment facilities—outpatient, day treatment, and residential treatment—in Chicago. There were 168.2 incidents of violent victimization per 1,000 persons per year, more than four times greater than the rate in the general population. Incidence ratios remained statistically significant even after the analysis controlled for sex and race-ethnicity.

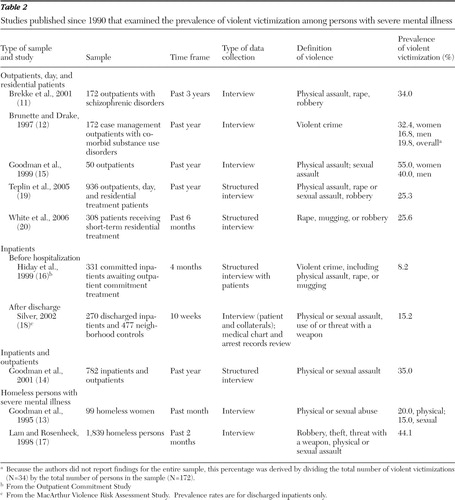

Prevalence.Table 2 shows that all ten studies examined self-reported prevalence of victimization. Prevalence varied because of differences in sample sizes, time frames, and type of sample. One study had too small a sample to generate reliable prevalence rates of relatively uncommon events such as violent victimization ( 15 ). Studies of treatment populations with larger samples (N≥100) found prevalence rates of recent violent victimization between 8.2% in the past four months ( 16 ) and 35.0% in the past year ( 14 ). The largest study of homeless persons with severe mental illness found that 44.0% had been violently victimized in the past two months ( 17 ). Among studies that assessed violent victimization in the past year—the same time frame as the NCVS—prevalence rates ranged from 25.3% ( 19 ) to 35.0% ( 14 ), compared with 2.9% in the NCVS.

|

Prevalence rates appear to vary by type of victimization. However, these differences may be attributable to the way that victimization was measured. For example, White and colleagues ( 20 ) asked only one question about victimization in the past six months. Other studies collected detailed information on the type of victimization ( 13 , 14 , 17 , 19 ).

Prevalence rates also varied by the type of sample. For example, 19.0% of the sample of outpatients and patients in residential treatment in the study by Teplin and colleagues ( 19 ) and 35.0% of the combined sample of inpatients and outpatients in the study by Goodman and colleagues ( 14 ) had been victims of physical assault in the past year. Similarly, prevalence of rape and sexual assault in the past year ranged from 2.6% among outpatients ( 19 ) to 12.7% in a combined sample of outpatients and inpatients ( 14 ). Prevalence of victimization among homeless persons with severe mental illness was generally higher than in treatment samples ( 13 , 17 ). Irrespective of the type of sample and type of victimization, prevalence was much higher in all studies listed in Table 2 than in the general population, as found in the NCVS ( 23 ).

Comparing perpetration of violence and violent victimization

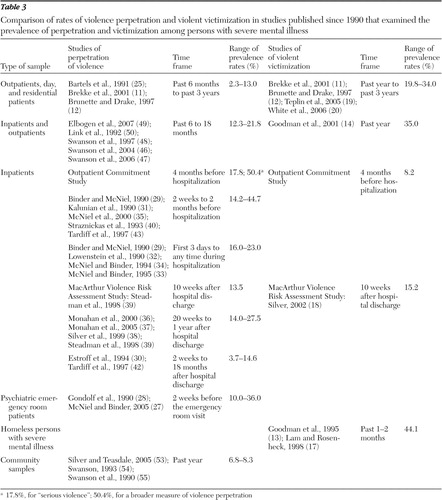

Are persons with severe mental illness more likely to be perpetrators of violence or victims of violence? Table 3 summarizes and compares the prevalence of violence perpetration and violent victimization from the studies in Table 1 and Table 2 .

|

Only three studies assessed perpetration and victimization among the same participants. Brekke and colleagues ( 11 ) found that among outpatients with schizophrenic disorders, 6.4% had contact with police for "aggression against others" in the past three years and 34.0% reported being violently victimized. The marked differences in rates may be attributable to the fact that violence perpetration was counted only if the person had contact with the criminal justice system; many violent behaviors do not come to the attention of the police or culminate in formal processing ( 57 ). Had the authors used a broader measure of violence, the reported differences between perpetration of violence and violent victimization might have been less dramatic. A study by Brunette and Drake ( 12 ) had similar findings; 6.4% of their sample had been physically aggressive in the past year, and 19.8% had been a victim of a violent crime in the past year. In the Outpatient Commitment Study, Swanson and colleagues ( 41 ) found that among committed inpatients, the prevalence of violence perpetration in the four months before commitment ranged from 17.8% for "serious violence" to 50.4% for a broader measure of violence; in contrast, 8.2% reported violent victimization ( 16 ).

Why was the prevalence of perpetration of violence so high in the Outpatient Commitment Study? Most likely, it was because participants were sampled soon after commitment. The authors did not indicate the proportion of individuals in the sample who were committed because of their violent behavior. The discrepancies between violence perpetration and violent victimization may also have resulted from differences in the definitions of violence. Victimization was narrowly defined as self-reported "violent crimes"; perpetration of violence referred to a range of violent behaviors elicited from patients and their collaterals as well as from hospital records.

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study provided some information about violence perpetration and violent victimization among discharged inpatients. The authors reported that 13.5% of the sample had perpetrated violence ( 39 ) and 15.2% had been victims ( 18 ) ten weeks after discharge from a psychiatric inpatient unit. However, because one report used a subsample ( 18 ), rates are not directly comparable.

Other studies listed in Table 3 show that irrespective of the type of sample and regardless of the time frame, violent victimization is more prevalent than violence perpetration. For example, among outpatients and residential patients with severe mental illness, 20.0% to 34.0%, depending on the time frame and gender, had been a victim of recent violence ( 11 , 12 , 19 , 20 ), compared with 2.0% to 13.0% who had perpetrated violence ( 11 , 12 , 25 ). Similarly, in samples that combined outpatients and inpatients, 35.0% reported violent victimization in the past year ( 14 ), compared with 12.0% to 22.0% who had perpetrated violence (depending on whether the time frame was 12 or 18 months and who reported recent perpetration of violence) ( 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ).

Conclusions

Perpetration of violence and violent victimization are more common among persons with severe mental illness than in the general population ( 19 , 53 , 54 , 55 ). Studies analyzing the Epidemiologic Catchment Area data found that approximately 2% of persons without a mental disorder perpetrated violence in the past year, compared with 7% to 8% of persons with severe mental illness ( 53 , 54 , 55 ). For victimization, the disparity between the general population (3%) and persons with severe mental illness (25%) is even greater, as found in the NCVS ( 19 ).

Overall, our review does not support the stereotype that persons with severe mental illness are typically violent ( 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ). This stereotype may persist, in part, because of researchers' focus on inpatients. Although fewer than 17% of persons with severe mental illness in the United States are hospitalized ( 58 ), nearly half of the studies that investigate violence among persons with severe mental illness examined only inpatients ( 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ). Among these, the largest and most well-cited studies focused on involuntarily committed inpatients. The Outpatient Commitment Study included only involuntarily committed inpatients. Two-fifths of the sample in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study had been involuntarily committed, a significant predictor of subsequent violence ( 45 ). Because commitment criteria include imminent dangerousness (to self or others) ( 44 ), findings derived from samples of involuntarily committed patients are generalizable only to the most acutely disturbed patients—those whose situations have required involvement of the courts.

How much violence in the United States is caused by persons with mental illness? One study found that overall, the attributable risk of mental illness to the perpetration of violence in the United States is approximately 2% ( 52 ); by comparison, two demographic variables—gender and age—are more powerful predictors of violence ( 52 ). Nearly 40% of arrests for serious violent crimes (murder, nonnegligent homicide, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault) are of males 24 years and younger ( 59 ).

Despite the small attributable risk of severe mental illness to perpetration of violence, negative stereotypes of persons with severe mental illness dominate the public's view ( 60 , 61 ) and behavioral scientists' focus. Among 39 studies that met our inclusion criteria, 79% (N=31) studied perpetration of violence. The focus on violence perpetration extended to nonempirical articles as well. A computerized search of MEDLINE and PsycINFO yielded 283 empirical or review articles mentioning crime victimization among persons with mental illness; more than 13 times that many articles were found on perpetration of violence ( 19 ).

Directions for future research

On the basis of our review, we suggest the following directions for research.

Focus on victimization. Symptoms of severe mental illness—poor judgment, impaired reality testing, and disorganized thought processes ( 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 )—and homelessness, a phenomenon common among persons with severe mental illness ( 13 , 17 ), increase susceptibility to violent victimization. To guide the development of effective interventions, the field needs studies of patterns of vulnerability, risk, and sequelae of violent victimization. For example, studies must investigate how clinical symptoms and environment (for example, homelessness, lifestyle, and impoverished neighborhoods) interact to affect victimization. Researchers must also investigate long-term consequences of victimization.

Study perpetration and victimization in the same sample using comparable definitions and measures. The field has been hampered by the paucity of studies that examine perpetration and victimization in the same sample and by the lack of consistency in definitions and measures within and across studies. We recommend that future studies use established, validated definitions and measures of violence and victimization. Standardized instruments such as the NCVS provide comprehensive data on the prevalence, incidence, and patterns of victimization, and results are comparable to national general population data. We also recommend multimethod, cross-validation designs (for example, use of self-reports and arrest records) and suggest that future investigators study incidence as well as prevalence.

Investigate community populations, not only persons in treatment. Nearly 90% of the studies of perpetration that we reviewed (27 of 31 studies) sampled patients from clinics or hospitals ( 11 , 12 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ). Among the studies that examined prevalence of victimization, all sampled persons in treatment ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ). We need information on the estimated five million persons with severe mental illness in the United States who do not receive treatment ( 66 ). Cost-effective strategies include adding items from the NCVS and from established assessments of violence to community-based epidemiologic surveys ( 19 ).

Improve the prediction of violence perpetration. Some of the positive symptoms of psychosis—persecutory delusions, suspiciousness, hallucinations, and grandiosity as well as symptoms that undermine internal control and threaten harm—increase the risk of perpetrating violence ( 47 , 48 , 67 , 68 , 69 ) (in contrast, see the article by Appelbaum and colleagues [ 70 ]). In addition, specific negative symptoms of psychosis—lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation, passive or apathetic social withdrawal, blunted affect, poor rapport, and difficulty with abstract thinking—may decrease the risk of serious violence ( 47 ). To improve the prediction of violence, however, the field must focus on a broader array of variables, not only on symptoms of mental illness. Multiple iterative classification trees are a promising approach, whereby researchers combine personal, clinical, contextual, and historical risk factors to predict the likelihood of future violence ( 37 , 71 , 72 ). However, this technique has been applied only to discharged psychiatric inpatients to predict their short-term outcomes (20 weeks). Studies should be replicated in other populations—outpatients and persons who are not in treatment—and should examine long-term outcomes. Understanding the key risk factors for violence will provide a foundation for effective prevention strategies.

Disentangle the causal relationships between severe mental illness, victimization, and perpetration. Perpetration of violence and violent victimization occur within a socioenvironmental context. Hiday ( 73 ) posited a theoretical model whereby social disorganization and poverty—phenomena common among many persons with severe mental illness—increase persons' vulnerability to victimization and their propensity to perpetrate violence. Repeated victimizations may lead to suspicion and mistrust, which in turn may lead to conflictive and stressful situations—in short, a cycle of victimization and perpetration ( 73 ). Future studies should examine how the socioenvironmental context moderates and mediates the relationship between victimization and perpetration.

Implications for treatment and mental health policy

We suggest the following steps to reduce the perpetration of violence and violent victimization among persons with severe mental illness.

Encourage mental health centers to assess risk of victimization and perpetration. Improving detection is the first step to improving services ( 19 ). Mental health service providers can then implement programs for persons at greatest risk. To reduce victimization, interventions should include information about modifiable risk factors, such as substance abuse, homelessness, medication adherence, and conflictual relationships, that can help persons with severe mental illness to develop skills that enhance personal safety and improve conflict management. To reduce perpetration of violence, interventions should address symptom management—identifying triggers, coping with psychotic symptoms or mood changes, and adhering to medication regimens.

Disseminate information about the relative risk of violence perpetration and violent victimization. To reach policy makers and the general public, researchers should disseminate research findings in lay journals and newspapers ( 74 ). Media campaigns on television and in newspapers may reduce stigma by improving the public's image of persons with severe mental illness. Increased public awareness may also stimulate needed community and federal support for employment, housing, and social services for persons with severe mental illness.

Reduce barriers to mental health treatment. Treatment that combines medication management, psychotherapy, and case management can decrease victimization ( 75 ) and violent behavior ( 45 , 76 , 77 ). However, persons with severe mental illness often face substantial barriers to receiving mental health services. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey found that 40% of persons with severe mental illness did not receive any care in a one-year period ( 58 ). Internal barriers, such as stigma associated with mental illness and denial of illness, may prevent persons from seeking care ( 58 , 78 ). Structural barriers include limited access to public transportation, transient living conditions that interfere with continuity of care, and language barriers ( 58 , 79 ). Reducing barriers to treatment could concomitantly reduce victimization and violent behavior.

Develop and evaluate innovative programs for persons with severe mental illness and comorbid substance use disorders. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration estimates that approximately half of persons with severe mental illness have also had a substance use disorder in their lifetime ( 80 ). Treating substance use disorders among persons with severe mental illness is crucial to reducing victimization and perpetration. Despite the importance of such treatment, the development of effective interventions for persons with comorbid mental and substance use disorders has lagged behind the need ( 81 ). Effective treatments will reduce exposure to environmental risks associated with substance abuse and thus the likelihood of victimization and perpetration.

Although society may regard persons with mental illness as dangerous criminals ( 8 , 10 ), our review of the literature shows that violent victimization of persons with severe mental illness is a greater public health concern than perpetration of violence. Although some symptoms of severe mental illness are correlated with violence, severe mental illness accounts for only a modicum of violence. Ironically, the discipline's focus on the perpetration of violence among inpatients may contribute to the negative stereotypes of persons with severe mental illness, which are often based on the label of "mental patient," not on observed behavior ( 82 , 83 ). We must balance the dual public health concerns of protecting the safety of the public and protecting persons with severe mental illness from criminal victimization.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by MERIT award R37-MH-47994 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and by grant R01-MH-54197 from the NIMH Division of Services and Intervention Research. This study could not have been accomplished without the contribution of Erin G. Romero, B.S.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Hiday VA: The social context of mental illness and violence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:122–137, 1995Google Scholar

2. Junginger J, McGuire L: Psychotic motivation and the paradox of current research on serious mental illness and rates of violence. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:21–30, 2004Google Scholar

3. Monahan J: Mental disorder and violent behavior: perceptions and evidence. American Psychologist 47:511–521, 1992Google Scholar

4. Monahan J, Steadman HJ: Crime and mental disorder: an epidemiological approach, in Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research, Vol 4. Edited by Tonry M, Morris N. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1983Google Scholar

5. Mulvey EP: Assessing the evidence of a link between mental illness and violence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:663–668, 1994Google Scholar

6. Torrey E: Violent behavior by individuals with serious mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:653–662, 1994Google Scholar

7. Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, et al: Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:4–7, 2000Google Scholar

8. Phelan J, Link B: The growing belief that people with mental illnesses are violent: the role of the dangerousness criterion for civil commitment. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33(suppl 1):S7–S12, 1998Google Scholar

9. Steadman HJ: Critically reassessing the accuracy of public perceptions of the dangerousness of the mentally ill. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22:310–316, 1981Google Scholar

10. Wahl OF: Public vs professional conceptions of schizophrenia. Journal of Community Psychology 15:285–291, 1987Google Scholar

11. Brekke JS, Prindle C, Bae SW, et al: Risks for individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community. Psychiatric Services 52:1358–1366, 2001Google Scholar

12. Brunette MF, Drake RE: Gender differences in patients with schizophrenia and substance abuse. Comprehensive Psychiatry 38:109–116, 1997Google Scholar

13. Goodman LA, Dutton MA, Harris M: Episodically homeless women with serious mental illness: prevalence of physical and sexual assault. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:468–478, 1995Google Scholar

14. Goodman LA, Salyers MP, Mueser KT, et al: Recent victimization in women and men with severe mental illness: prevalence and correlates. Journal of Traumatic Stress 14:615–632, 2001Google Scholar

15. Goodman LA, Thompson KM, Weinfurt K, et al: Reliability of reports of violent victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder among men and women with serious mental illness. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:587–599, 1999Google Scholar

16. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, et al: Criminal victimization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:62–68, 1999Google Scholar

17. Lam JA, Rosenheck R: The effect of victimization on clinical outcomes of homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:678–683, 1998Google Scholar

18. Silver E: Mental disorder and violent victimization: the mediating role of involvement in conflicted social relationships. Criminology 40:191–212, 2002Google Scholar

19. Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, et al: Crime victimization in adults with severe mental illness: comparison with the National Crime Victimization Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:911–921, 2005Google Scholar

20. White MC, Chafetz L, Collins-Bride G, et al: History of arrest, incarceration and victimization in community-based severely mentally ill. Journal of Community Health 31:123–135, 2006Google Scholar

21. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Archives of General Psychiatry 62:617–627, 2005Google Scholar

22. Milazzo-Sayre LJ, Henderson MJ, Manderscheid RW, et al: Selected characteristics of adults treated in specialty mental health care programs, United States, 1997, in Mental Health, United States, 2002. DHHS pub no (SMA) 3938. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2004Google Scholar

23. US Department of Justice: Crime Victimization Survey, 1992–1999, 9th ed. Ann Arbor, Mich, Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2001Google Scholar

24. Gordis L: Epidemiology. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2004Google Scholar

25. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA, et al: Characteristic hostility in schizophrenic outpatients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:163–171, 1991Google Scholar

26. Boles SM, Johnson PB: Violence among comorbid and noncomorbid severely mentally ill adults: a pilot study. Substance Abuse 22:167–173, 2001Google Scholar

27. McNiel DE, Binder RL: Psychiatric emergency service use and homelessness, mental disorder, and violence. Psychiatric Services 56:699–704, 2005Google Scholar

28. Gondolf EW, Mulvey EP, Lidz CW: Characteristics of perpetrators of family and nonfamily assaults. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:191–193, 1990Google Scholar

29. Binder RL, McNiel DE: The relationship of gender to violent behavior in acutely disturbed psychiatric patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51:110–114, 1990Google Scholar

30. Estroff SE, Zimmer C, Lachicotte WS, et al: The influence of social networks and social support on violence by persons with serious mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:669–679, 1994Google Scholar

31. Kalunian DA, Binder RL, McNiel DE: Violence by geriatric patients who need psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51:340–343, 1990Google Scholar

32. Lowenstein M, Binder RL, McNiel DE: The relationship between admission symptoms and hospital assaults. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:311–313, 1990Google Scholar

33. McNiel DE, Binder RL: Correlates of accuracy in the assessment of psychiatric inpatients' risk of violence. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:901–906, 1995Google Scholar

34. McNiel DE, Binder RL: The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:133–137, 1994Google Scholar

35. McNiel DE, Eisner JP, Binder RL: The relationship between command hallucinations and violence. Psychiatric Services 51:1288–1292, 2000Google Scholar

36. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Developing a clinically useful actuarial tool for assessing violence risk. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:312–319, 2000Google Scholar

37. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC, et al: An actuarial model of violence risk assessment for persons with mental disorders. Psychiatric Services 56:810–815, 2005Google Scholar

38. Silver E, Mulvey EP, Monahan J: Assessing violence risk among discharged psychiatric patients: toward an ecological approach. Law and Human Behavior 23:237–255, 1999Google Scholar

39. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393–401, 1998Google Scholar

40. Straznickas KA, McNiel DE, Binder RL: Violence toward family caregivers by mentally ill relatives. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:385–387, 1993Google Scholar

41. Swanson J, Swartz M, Estroff S, et al: Psychiatric impairment, social contact, and violent behavior: evidence from a study of outpatient-committed persons with severe mental disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33(suppl 1):S86–S94, 1998Google Scholar

42. Tardiff K, Marzuk PM, Leon AC, et al: A prospective study of violence by psychiatric patients after hospital discharge. Psychiatric Services 48:678–681, 1997Google Scholar

43. Tardiff K, Marzuk PM, Leon AC, et al: Violence by patients admitted to a private psychiatric hospital. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:88–93, 1997Google Scholar

44. Policy Involuntary Commitment and Court-Ordered Treatment, 2002. Arlington, Va, National Alliance on Mental Illness. Available at www.nami.org/content/contentgroups/policy/updates/involuntarycommitmentandcourt-orderedtreatment.htmGoogle Scholar

45. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Silver E, et al: Rethinking Risk Assessment: The MacArthur Study of Mental Disorder and Violence. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001Google Scholar

46. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB: Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications in reducing violent behavior among persons with schizophrenia in community-based treatment. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:3–20, 2004Google Scholar

47. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, et al: A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:490–499, 2006Google Scholar

48. Swanson J, Estroff S, Swartz M, et al: Violence and severe mental disorder in clinical and community populations: the effects of psychotic symptoms, comorbidity, and lack of treatment. Psychiatry 60:1–22, 1997Google Scholar

49. Elbogen EB, Mustillo S, Van Dorn R, et al: The impact of perceived need for treatment on risk of arrest and violence among people with severe mental illness. Criminal Justice and Behavior 34:197–210, 2007Google Scholar

50. Link BG, Andrews H, Cullen FT: The violent and illegal behavior of mental patients reconsidered. American Sociological Review 57:275–292, 1992Google Scholar

51. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Essock SM, et al: The social-environmental context of violent behavior in persons treated for severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 92:1523–1531, 2002Google Scholar

52. Corrigan PW, Watson AC: Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey on the frequency of violent behavior in individuals with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Research 136:153–162, 2005Google Scholar

53. Silver E, Teasdale B: Mental disorder and violence: an examination of stressful life events and impaired social support. Social Problems 52:62–78, 2005Google Scholar

54. Swanson JW: Alcohol abuse, mental disorder, and violent behavior: an epidemiologic inquiry. Alcohol Health and Research World 17:123–132, 1993Google Scholar

55. Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Ganju VK, et al: Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:761–770, 1990Google Scholar

56. Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al: A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 49:1373–1379, 1996Google Scholar

57. Crime in the United States 2004, Uniform Crime Reports. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2005Google Scholar

58. Narrow W, Regier D, Norquist G, et al: Mental health service use by Americans with severe mental illnesses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:147–155, 2000Google Scholar

59. Crime in the United States, 2006. US Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Sept 2007. Available at www.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2006Google Scholar

60. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, et al: Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health 89:1328–1333, 1999Google Scholar

61. Pescosolido BA, Boyer CA: How do people come to use mental health services? Current knowledge and changing perspectives, in A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories, and Systems. Edited by Horwitz AV, Scheid TL. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1999Google Scholar

62. Goodman LA, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, et al: Physical and sexual assault history in women with serious mental illness: prevalence, correlates, treatment, and future research directions. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:685–696, 1997Google Scholar

63. Hiday VA, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al: Victimization: a link between mental illness and violence? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 24:559–572, 2001Google Scholar

64. Marley JA, Buila S: Crimes against people with mental illness: types, perpetrators, and influencing factors. Social Work 46:115–124, 2001Google Scholar

65. Sells DJ, Rowe M, Fisk D, et al: Violent victimization of persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 54:1253–1257, 2003Google Scholar

66. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Zhao S, et al: The 12-month prevalence and correlates of serious mental illness (SMI), in Mental Health, United States, 1996. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996Google Scholar

67. Link BG, Stueve A: Psychotic symptoms and the violent/illegal behavior of mental patients compared to community controls, in Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Edited by Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994Google Scholar

68. Swanson JW, Borum R, Swartz MS, et al: Psychotic symptoms and disorders and the risk of violent behaviour in the community. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 6:309–329, 1996Google Scholar

69. Junginger J: Psychosis and violence: the case for a content analysis of psychotic experience. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:91–103, 1996Google Scholar

70. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J: Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:566–572, 2000Google Scholar

71. Banks S, Robbins PC, Silver E, et al: A multiple-models approach to violence risk assessment among people with mental disorder. Criminal Justice and Behavior 31:324–340, 2004Google Scholar

72. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: The Classification of Violence Risk. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 24:721–730, 2006Google Scholar

73. Hiday VA: Understanding the connection between mental illness and violence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 20:399–417, 1997Google Scholar

74. Sommer R: Dual dissemination: writing for colleagues and the public. American Psychologist 61:955–958, 2006Google Scholar

75. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, et al: Impact of outpatient commitment on victimization of people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1403–1411, 2002Google Scholar

76. O'Keefe C, Potenza DP, Mueser KT: Treatment outcomes for severely mentally ill patients on conditional discharge to community-based treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:409–411, 1997Google Scholar

77. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Borum R, et al: Involuntary out-patient commitment and reduction of violent behaviour in persons with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:324–331, 2000Google Scholar

78. Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al: Stigma as a barrier to recovery: perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatric Services 52:1615–1620, 2001Google Scholar

79. Van Dorn RA, Elbogen EB, Redlich AD, et al: The relationship between mandated community treatment and perceived barriers to care in persons with severe mental illness. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 29:495–506, 2006Google Scholar

80. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Clark RE, et al: Evaluating Substance Abuse in Persons With Severe Mental Illness. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1995. Available at mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/cmhs/communitysupport/research/toolkits/pn6toc.aspGoogle Scholar

81. Report to Congress on the Prevention and Treatment of Co-occurring Substance Abuse Disorders and Mental Disorders. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002Google Scholar

82. Link BG: Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review 52:96–112, 1987Google Scholar

83. Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, et al: The social rejection of former mental patients: understanding why labels matter. American Journal of Sociology 92:1461–1500, 1987Google Scholar