Assessing New Patient Access to Mental Health Providers in HMO Networks

Network contracts with providers are one mechanism health plans may use to control health care costs ( 1 ). Typically, health plans provide a list of providers (network provider panels) from whom enrollees may receive care at reduced cost sharing. Health plans may negotiate reduced prices (per unit of service) with providers in exchange for volume ( 2 ), limit network provider panels to providers with preferred treatment styles ( 3 ), or establish various incentives (such as performance targets or prior authorization) to improve quality or reduce quantity ( 4 ). Concerns have been raised that reduced reimbursement and increased administrative burden for providers may reduce provider participation in network provider panels such that plan enrollees are unable to obtain needed care.

Although network adequacy has been questioned across medical specialties, mental health advocates have been particularly vocal in raising concerns ( 5 ). Apprehensions may be warranted given evidence that incentives to limit care are particularly strong for mental health ( 6 ). Research indicates that use of mental health services affects choice of health plan ( 7 , 8 ). Mental illnesses are often persistent, and individuals with these disorders tend to use more health services than other consumers ( 9 , 10 ). Because more generous coverage attracts persons seeking mental health care, insurers have a financial incentive to compete to avoid enrolling these individuals by creating barriers to care ( 11 ). Also, the RAND Health Insurance Experiment demonstrated that increased use of services by consumers in response to decreased cost sharing for ambulatory mental health care was roughly double that observed for medical services under indemnity insurance ( 12 , 13 ). Heightened concerns that insured persons who do not have to pay the full costs of care will use more services (moral hazard) may prompt plans to impose greater supply side constraints.

Few empirical studies have attempted to quantify the magnitude of problems with network access. Wilk and colleagues ( 14 ) surveyed 2,323 psychiatrists about whether they were accepting new patients. Although 85% of psychiatrists were accepting new patients overall, rates of acceptance differed significantly across payer type, with 77% accepting new self-pay patients, 44% accepting patients with Medicaid, 65% accepting patients with unmanaged private insurance, and 53% accepting patients with managed private insurance. The authors concluded that their findings "suggest a serious public health problem of access to psychiatric care in privately managed insurance plans and Medicaid." This study did not examine network access to mental health providers who are not psychiatrists. The study's focus on psychiatrists reduces its generalizability, because 81% of providers treating patients in the mental health system are not psychiatrists ( 15 ).

This topic captured headlines in Connecticut with the release of a survey by the attorney general's office in April 2007 documenting problems experienced by families in obtaining care from child psychiatrists. The report concluded that "some managed care plans have significantly misstated the participating providers available to treat the children and adolescents enrolled in their plans" ( 5 ).

In this study, we assessed network access to a broad range of mental health providers. We conducted a telephone survey to address four research questions: Is the information available to health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollees regarding network provider panels accurate? What share of in-network providers is accepting new patients, and does this rate differ significantly by plan? For different provider types, how many calls are needed to obtain a new appointment? Among in-network providers who do not accept new patients, what reasons are given for not accepting new patients?

Methods

Between December 2006 and March 2007 we surveyed by telephone mental health providers included in the networks of the six HMOs operating in Connecticut. These six HMOs provided health insurance to 1,261,529 privately insured enrollees in 2006 ( 16 ). Of these six HMOs, two contracted with managed behavioral carve-out companies. We employed a stratified random sample treating the six HMOs as separate strata and selecting random samples from each stratum. Strata sample sizes are proportional to the size of each HMO's network. The sampling frame was all mental health providers listed in the hard copy listing of network providers distributed by the six HMOs. A more regularly updated list of providers is available on HMO Web sites. Online listings are expected to be updated more regularly to account for periodic changes in provider contracting and contact information. From our original sample frame of 667 providers, we excluded the 55 sampled providers not listed as being in a network on HMO Web sites as of December 2006.

Next, we identified 105 sampled providers listed inaccurately. We defined a listing as inaccurate if the provider was retired, had moved out of state, did not have a working phone number (listed in either the hard copy publication or online), left the group practice or was no longer practicing, or was deceased. Some providers were not practicing temporarily because of maternity or medical leave, and we counted them as nonrespondents with accurate listings. Our final sample included 507 providers. We surveyed 366 providers by telephone for a 72% response rate.

Before surveying the providers in our sample, we checked the online lists for all six health plans to determine whether a given provider was included in the network for other plans beyond the sampled plan. A common characteristic of networks is that a provider may contract with multiple plans. The survey instrument was designed to ask respondents questions multiple times (once for each HMO for which they were listed as being an in-network provider). For example, if a respondent was listed by four different HMOs as being an in-network provider, that provider would be asked the relevant questions for each individual plan.

The 366 providers participated in an average of 3.66 plans for a total of 1,342 provider-plan observations. [An appendix showing the number of providers and provider plans sampled and the final number to be included in the study is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] The survey also allowed us to determine whether a provider self-identified as being in a network for a given HMO and to compare this with whether the HMO listed the respondent as being in the network. Although the information initially collected from plans indicated 1,405 plan-provider combinations, a small subset of providers (N=63) did not self-identify as being part of a given HMO network provider panel, despite being included on the online network listing. We pretested the survey to evaluate the reliability of the instrument, the ease of administration, and respondent burden. We received an institutional review board exemption (45 CFR 46.101(b)(2)) from the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee on November 21, 2006.

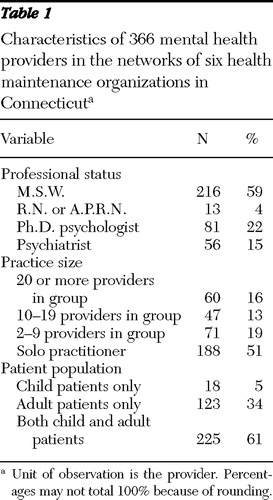

We categorized providers by credentialing, size of practice, and patient population treated. Respondents were coded as social workers (M.S.W. degree), registered or advance practice nurses (R.N. or A.P.R.N.), doctoral-level psychologists (Ph.D.), or psychiatrists. Practice size ranged from solo practitioners, small group practices (two to nine providers), midsize group practices (ten to 19 providers), or large group practices (20 or more providers). Providers described themselves as treating adults only, children only, or both.

For each HMO in which a provider was listed as in network, we asked the provider whether he or she was accepting new patients. We defined accepting new patients as being able to schedule an appointment within two weeks from the time of initial contact. We also asked each provider whether he or she was accepting new self-pay patients. For providers not accepting new patients for a given health plan, we asked whether each of the following was very important, somewhat important, not too important, or not important at all in explaining why they were not accepting new patients for a given HMO: reimbursement rates were too low, no appointment was available, utilization review or prior authorization were too cumbersome, or some other reason. For those responding "some other reason," we asked them to describe this reason.

We analyzed providers' acceptance rates of new patients at the provider-plan level (N=1,342) to account for the fact that a provider participating in multiple HMO network provider panels might accept new patients for some plans but not for others. We also examined whether acceptance rates differed among the six HMOs and for self-pay patients. In addition, we examined new patient acceptance rates at the provider-plan level by provider characteristics descriptively and by using logistic regression. In logistic regression models, we included five dichotomous variables indicating the specific plan to determine whether there were differences among plans. Standard errors from logistic regression models were adjusted to account for multiple observations for the same provider.

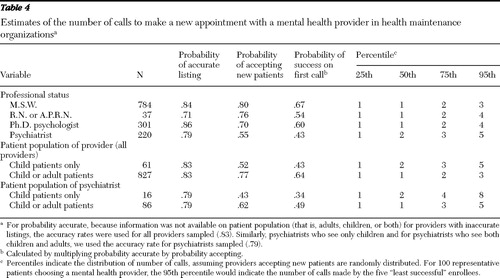

For different provider types, we modeled the number of calls necessary to obtain a new appointment. A binomial cumulative distribution function indicates (for a given probability level) the probability an individual will have to make a given number of calls before successfully scheduling an appointment. We calculated both the probability of success on the first call and the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of the distribution of number of calls, assuming providers accepting new patients are randomly distributed. For 100 representative patients choosing a mental health provider, the 95th percentile would indicate the number of calls made by the five "least successful" enrollees. We incorporated both the accuracy of listings and the share of providers accepting new patients to estimate the number of calls a consumer would need to make to schedule a new appointment. Finally, among providers who were not accepting new patients for a given HMO, we descriptively report the reasons cited for this decision.

Results

Of our initial sample of 612 providers from the six HMOs in Connecticut (excluding those not listed on HMO Web sites), 17% were not accurate (N=105). These providers had retired (N=5), had moved out of state (N=6), had a nonworking phone number (N=51), had left the group practice or were no longer practicing (N=41), or were deceased (N=2).

Table 1 reports descriptive characteristics of survey respondents (N=366). The professional makeup of the sample is similar to recent national estimates ( 17 ). Fifty-nine percent were social workers, 22% were psychologists, 4% were registered or advance practice nurses, and 15% were psychiatrists. Consistent with national estimates ( 18 ), a majority were solo practitioners (51%), with the remainder divided among small practices (19%), medium practices (13%), and large practices (16%). A majority of providers treated both child and adult patients (61%), with 34% treating adults only and 5% treating children only.

|

Table 2 indicates the share accepting new HMO patients at the provider-plan level. We found a 73% acceptance rate for HMO patients. This rate did not vary significantly across the six plans (range of 71% to 75%). Psychiatrists and providers treating children only were significantly less likely than other providers to accept new HMO patients. Among the small subgroup of psychiatrists in our sample who stated that they treated only child patients (N=16), 44% (N=7) reported accepting new HMO patients (results not shown). Among the somewhat larger group of psychiatrists treating either children only or children and adults (N=102), 59% (N=60) reported accepting new HMO patients (results not shown). Table 2 also includes information on provider acceptance rates for self-pay patients (N=366). The provider acceptance rate for these new patients was only slightly higher (76%) than that for HMO patients. For self-pay patients, psychiatrists were also significantly less likely than social workers and psychologists to accept new patients.

|

Logistic regression results in Table 3 are consistent with descriptive findings. Psychologists and psychiatrists had significantly lower odds of accepting new patients, compared with social workers. Likewise, compared with providers treating children only, those treating both children and adults were significantly (p<.10) more likely to accept new patients. We compared logistic regression models with and without plan dummy variables; a likelihood ratio test indicated no additional explanatory power from adding plan dummies, suggesting no plan-level differences in rates of accepting new patients.

|

In Table 4 , we incorporate both accuracy of network listings and providers' acceptance rates of new patients to estimate across plans the number of calls an enrollee would need to make to schedule a new appointment. We assume the probability a call is successful is independent of the success of prior calls. Of 100 patients attempting to make an appointment with a social worker, 67 would be successful on their first call. In the extreme case, the five patients (of the initial 100) facing the greatest difficulty would need to make only three calls to schedule an appointment with a social worker. The situation is more challenging for those seeking treatment with a psychiatrist. Of 100 patients, only 43 would be successful on their first try. The five with the most difficulty would need to attempt contact with five distinct psychiatrists before scheduling an appointment. Making an appointment with a psychiatrist treating children only was substantially more challenging. In this case, only 34% of patients would be successful on their first call, and the five least successful patients (of the initial 100) would need to make eight calls to schedule a new appointment with a psychiatrist treating only children.

|

The respondents provided reasons for not accepting new patients. Providers could cite more than one reason as important. Twenty-seven percent (N=357) of providers listed on HMO networks (at the provider-plan level) indicated that they were not able to schedule appointments with new patients within a two-week period. A majority of providers cited the lack of available appointments as a very important or somewhat important reason for not accepting new HMO patients (N=223, or 62%). Substantially fewer providers noted low reimbursement (N=21, or 6%) or cumbersome processes for utilization review or prior authorization (N=35, or 10%) to explain why they were not accepting new patients. Ten percent (N=36) identified other reasons as important, including cumbersome or slow reimbursement, plans to retire or close the business, inability to afford to see new patients, and practice limited to self-pay patients. Eighteen percent of providers (N=64) not accepting new patients offered no reason as being important in explaining their decision.

Discussion

This study aimed to quantify the burden that HMO enrollees face in accessing mental health services. We found that network listings for HMO mental health providers were inaccurate 17% of the time. Among those with accurate listings, 27% were not accepting new patients. We found no significant differences by plan in acceptance rates for new patients. That is, of the 366 survey respondents, only seven reported differences in accepting new patients by plan. This is consistent with our finding that a majority of providers not accepting new patients cited "no available appointments" as the primary reason, rather than plan-specific factors (that is, reimbursement rates, utilization review, or prior authorization processes).

There are some limitations of this study worth noting. First, the study reports on mental health providers in Connecticut participating in at least one private HMO plan. Generalizability of results to providers operating in other states or under other insurance arrangements (such as preferred provider organizations) may be limited. Likewise, results may not be indicative of access to providers among public program enrollees (for example, Medicaid and Medicare enrollees). Second, we did not examine the geographic diversity of providers. We do not know whether providers who were not accepting new patients were located in specific geographic areas, making it particularly difficult for patients in these areas to locate a provider taking new patients. Third, we relied on self-reports by providers who may have been reluctant to report that they are motivated by financial concerns. Fourth, primary care physicians provide an important referral function in getting individuals into mental health treatment (and often they provide mental health care directly). It may be easier for patients to find a provider than indicated by our study, because primary care physicians may have more knowledge about which providers are accepting new patients. Finally, some individuals seeking mental health care may be interested in obtaining services from a provider with specialized training (for example, in couples' therapy or in treating posttraumatic stress disorder or eating disorders). We were unable to assess the availability of specialized mental health services within HMO networks.

Despite these limitations, a number of strengths of our approach differentiate this study from prior research. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine accuracy of the listing of HMO network providers as an indicator of access. Second, we surveyed a fuller spectrum of mental health professionals, whereas prior studies focused on psychiatrists only. Third, by using online network provider panel listings to determine our sample, our approach takes into account the difficulty of keeping hard copies of provider listings up to date. Finally, compared with other provider surveys, our response rate was high (72%), reducing validity concerns related to nonrandom response bias.

Taken together, our findings that HMO network listings for mental health providers were inaccurate 17% of the time and our findings that 27% of providers with accurate listings were not accepting new patients indicate a potential access problem. This research highlights the importance of examining access across mental health disciplines. Our calculation of the number of calls patients might expect to make to schedule an appointment suggests that network access is not a major problem for health plan enrollees seeking mental health care from a social worker. More than half of patients seeking treatment will succeed in scheduling an appointment on their first phone call, and even the most unlucky patients will schedule an appointment within three calls. However, scheduling an appointment with a psychiatrist, particularly a child psychiatrist, appears to be more difficult. Although the median patient who is seeking a psychiatrist will be able to schedule an appointment within two calls, five out of 100 patients will need to make five calls. For an appointment with a psychiatrist treating only children, five out of 100 patients will need to make eight calls. This finding is particularly worrisome in the case of sicker patients or parents of children with a severe emotional disturbance, who may have fewer resources to circumvent barriers to care. Last year in Connecticut, one parent testified in the state legislature that of 90 names on a list of psychiatrists in network for her HMO, she was not able to find a single one accepting new patients ( 19 ). One goal of this study was to put parameters around the level of effort a consumer or parent would need to exert in successfully contacting a provider. Our results suggest that the experience of this parent constitutes an extremely rare event.

There are several potential explanations for the difficulty in scheduling appointments with child psychiatrists. First, a shortage of child psychiatrists may make it difficult for HMOs to contract with a sufficient number, regardless of payment level or administrative burden. Although the national shortage of child psychiatrists is well documented ( 19 ), the state of Connecticut has the third-highest ratio of child psychiatrists per youth (behind Hawaii and Massachusetts). Although there is little agreement regarding the optimal number of child psychiatrists per child, the ratio in Connecticut (19.2 per 100,000 children) exceeds the ratio of 14.4 per 100,000 recommended in the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee Report ( 6 ).

A second explanation is that by making it easy to find an appointment with lower-cost providers (for example, social workers), HMOs are intentionally steering patients to lower-cost treatment options. This strategy is efficient if it produces similar health outcomes at lower costs, but it could be detrimental if patients with serious conditions receive suboptimal care.

A third explanation is that HMOs are trying to discourage enrollment among persons with severe mental health conditions—a group that might have strong preferences regarding provider type. One policy response to combat risk selection by health insurance plans is enactment of parity legislation. Although Connecticut passed a comprehensive state parity law in 2002, this study provides evidence that some barriers to mental health care remain. Passage of a comprehensive federal parity law by the U.S. Congress in October of this year could help to even the playing field among plans. However, although parity prohibits use of benefit limits, health plans could still use restrictive networks to reduce access to services ( 6 ).

Our findings highlight the question, How many calls are too many? Depending on the circumstance, an individual in need of mental health treatment may find it difficult to take the initial step of seeking treatment. Successful contact on the first or second call may be consequential in determining whether care is initiated. It is worth noting that currently, there are no adequacy guidelines for managed care networks (for example, regulating a minimal threshold of network providers accepting new patients). Although our results suggest that few enrollees will have difficulty scheduling an appointment with certain types of mental health providers, those experiencing access problems may have the most to gain from obtaining high-quality care quickly. In the private market, employers may take a role in establishing an acceptable threshold of network adequacy. One option for employers is to create incentives or mandates to ensure minimum ratios of psychiatrists to enrollees. However, such policies may be difficult to regulate.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

A pilot grant from the Connecticut Office of the Healthcare Advocate provided funding to support survey data collection.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Glied S: Managed care, in Handbook of Health Economics: Vol 1A. Edited by Culyer A, Newhouse JP. Amsterdam, Elsevier Press, 2000Google Scholar

2. Cutler DM, McClellan M, Newhouse JP: How does managed care do it? Rand Journal of Economics 31:526–548, 2002Google Scholar

3. Ma CA, McGuire TG: Costs and incentives in a behavioral health carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):53–69, 1998Google Scholar

4. Ma CA, McGuire TG: Network incentives in managed health care. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 11:1–35, 2002Google Scholar

5. Blumental R, Milstein J: Connecticut Children Losing Access to Psychiatric Care: A Report of the Attorney General and Child Advocate's Investigation of Mental Health Care Available to Children in Connecticut. Hartford, Office of the Connecticut Attorney General, 2007Google Scholar

6. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Economics and mental health, in Handbook of Health Economics. Edited by Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP. Amsterdam, Elsevier Press, 2000Google Scholar

7. Deb PJ, Rubin V, Wilcox-Gok V, et al: Choice of health insurance by families of the mentally ill. Health Economics 5:61–76, 1996Google Scholar

8. Perneger TV, Allaz AF, Etter JF, et al: Mental health and choice between managed care and indemnity health insurance. American Journal of Psychiatry 52:1020–1025, 1995Google Scholar

9. Frank RG, Glazer J, McGuire TG: Measuring adverse selection in managed health care. Journal of Health Economics 19:829–854, 2000Google Scholar

10. Ellis RP: The effect of prior year health expenditures on health coverage plan choice, in Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research. Edited by Scheffler RM, Rossiter LF. Greenwich, Conn, JAI Press, 1998Google Scholar

11. Frank RG, Glazer J, McGuire TG: Measuring adverse selection in managed health care. Journal of Health Economics 19:829–854, 2000Google Scholar

12. Manning WG, Wells K, Buchanan J, et al: Effects of Mental Health Insurance: Evidence From the Health Insurance Experiment. Santa Monica, Calif, RAND, 1989Google Scholar

13. Newhouse JP: Free for All? Lessons From the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1993Google Scholar

14. Wilk JE, West JC, Narrow WE, et al: Access to psychiatrists in the public sector and in managed health plans. Psychiatric Services 56:408–410, 2005Google Scholar

15. Scheffler RM, Kirby PB: The occupational transformation of the mental health system. Health Affairs 22(5):177–188, 2003Google Scholar

16. A Comparison of Managed Care Organizations in Connecticut. Hartford, State of Connecticut Insurance Department, Oct 2006Google Scholar

17. Cunningham R: Professionalism reconsidered: physician payment in a small-practice environment. Health Affairs 23(6):36–47, 2004Google Scholar

18. Hathaway W: Kids' Mental Health Care Imperiled: Survey Says 50 Percent of Psychiatrists Reject Private Insurance for the Young. Hartford Courant, Apr 13, 2007. Available at www.hartfordinfo.org Google Scholar

19. Thomas CR, Holzer CE: The continuing shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 45:1023–1029, 2006Google Scholar