Disparity in Depression Treatment Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations in the United States

To respond to the Public Health Service's Healthy People 2010 initiative for minority populations, investigators must first ascertain at a national level the magnitude of disparities in service utilization for depression. Despite recent advances in the treatment of mental illness and considerable efforts to improve quality of and access to treatment ( 1 ), there appears to be a significant mismatch between need and treatment in the United States ( 2 ). There is controversy about disparities in quality of care ( 3 ) at a national level, because on that large overall scale there are few ethnic and racial disparities for some chronic conditions. Yet there is evidence of striking quality disparities across some groups for psychiatric conditions ( 4 , 5 , 6 ). Part of the discrepancy comes from differences in the ethnic and racial groups studied, whether studies are regional or national, and whether the assessment of need for depression care used diagnostic interviews versus screeners for depression.

Prior work on racial and ethnic disparities in depression treatment has been limited by the scarcity of national samples that include a rich array of diagnostic and quality indicators and large numbers of non-English-speaking minority respondents. With this study we took advantage of a unique opportunity to estimate disparities in access to and quality of depression care by using pooled data from the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES) ( 7 ). The three studies that constitute the CPES include the same measures of need and quality, include significant numbers of non-English-speaking persons belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups, and are the most current and comprehensive available to study depression treatment for racial and ethnic minority populations. Using a system cost-effectiveness framework ( 8 , 9 ), we evaluated whether individuals who could benefit from depression treatment were either not treated or inadequately treated. By this framework, not treating people who could benefit from treatment is a missed opportunity to improve health, and treating people who do not need care increases spending without commensurate health effects.

Methods

The CPES combined sample

The University of Michigan Survey Research Center (SRC) collected data for the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), collected between 2003 and 2003 ( 10 ); the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), collected between 2001 and 2003 ( 11 ); and the National Survey of American Life (NSAL), collected between 2001 and 2003 ( 12 ). Together, these studies are known as the CPES, and they used an adaptation of a multiple-frame approach to estimation and inference for population characteristics ( 13 , 14 ). This allows integration of design-based analysis weights to combine data sets as though they were a single, nationally representative study ( 7 ). Design and methodological information can be found at the CPES Web site ( 7 ).

Each study in CPES focused on collection of epidemiological data on mental disorders and service usage of the general population, with special emphasis on minority groups ( 15 ). Interviews for the studies were conducted by professional interviewers from the SRC, with 92.5% of interviews in English and 7.5% in other languages (Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese). As described in detail elsewhere ( 16 ), the NLAAS is a nationally representative survey of household residents age 18 and older in the noninstitutionalized Latino and Asian populations of the coterminous United States. The final sample included 2,554 Latinos and 2,095 Asian Americans.The weighted response rates were 73.2% for the total sample, 75.5% for Latinos, and 65.6% for Asians ( 17 ).

The NCS-R is a nationally representative sample with a response rate of 70.9%. Eligible respondents were English-speaking, noninstitutionalized adults age 18 or older living in civilian housing in the coterminous United States. The NCS-R was administered in two parts. Part 1 was administered to all English-speaking respondents and included core diagnostic assessments. A subset of part 1 respondents also completed part 2 of the survey, which included additional batteries of questions addressing service use, consequences, and other correlates of psychiatric illness and additional disorders, with measures identical to those in the NLAAS.

The NSAL is a nationally representative survey of household residents in the noninstitutionalized black population and included 3,570 African Americans and 1,621 black respondents of Caribbean descent. The NSAL response rate was 70.9% for the African-American sample and 77.7% for the black Caribbean sample ( 18 ). Interviews were done in English. We used a pooled sample (N=8,762) of data from Asians and Latinos from the NLAAS, non-Latino whites from the NCS-R part 2, and African Americans from the NSAL. Race and ethnicity categories were based on respondents' self-reports to questions based on U.S. census categories. The institutional review boards of all participating institutions approved all study procedures.

Diagnostic assessment

In the CPES, the presence of psychiatric disorders over a person's lifetime and in the past 12 months, and the presence of subthreshold depressive disorder or minor depressive disorder were evaluated via the World Mental Health survey initiative's World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) ( 19 ). Diagnoses are based on DSM-IV diagnostic systems. Findings showed good concordance between DSM-IV diagnoses based on the WMH-CIDI and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders ( 20 ). Using the WMH-CIDI ( 19 ), we classified the pooled sample, who responded to the NLAAS, NCS-R part 2, or NSAL, into five groups: currently depressed respondents, who met criteria for a past-year diagnosis of major depression or dysthymia (N=1,082); respondents with subthreshold symptoms, who did not meet criteria for a past-year diagnosis of major depression or dysthymia (N=158); lifetime depressed respondents, who met criteria for lifetime major depression or dysthymia but who did not meet criteria for past-year depression or dysthymia (N=1,230); respondents who met past-year criteria for disorders other than depression (N=919); and the no-need group, respondents who did not meet past-year criteria for any psychiatric or substance use disorder assessed (N=7,680).

Our main sample for estimating disparities in access included the 8,762 respondents who belonged to the first and fifth groups—those with current depression (N=1,082) and the no-need group (N=7,680). In models of disparities in the quality of depression treatment, our sample was further limited to 880 respondents who used services in the past year. Sensitivity analyses for access to and quality of depression care yielded an additional 158 persons with subthreshold symptoms, whom we considered in the sensitivity analyses as respondents with depression.

Role impairment and chronic medical conditions

Functional impairment was measured by the World Health Organization Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule ( 21 ). For the domains of cognition, mobility, self-care, and social functioning, we asked the number of days in the past 30 when health-related or mental health-related problems restricted ability to carry out related tasks. We measured the number of chronic medical conditions on the basis of respondents' endorsement of any of the following over their lifetime: arthritis or rheumatism, an ulcer in the stomach or intestine, cancer, high blood pressure, diabetes or high blood sugar, heart attack, stroke, asthma, tuberculosis, any other chronic lung disease, HIV infection, or AIDS.

Access to and quality of depression treatment

All CPES respondents were asked the same battery of questions about past-year mental health services and use of prescription medication (name of medication, length of use in the past year, and number of days that medication was used in the past month) for problems related to their emotions, nerves, substance use, energy, concentration, sleep, or ability to cope with stress. To define access to mental health care, we assessed whether the respondent received any mental health treatment, defined as at least one visit to a specialty mental health provider or general medical provider for mental health care in the past year. General medical sector providers included general practitioners, family doctors, nurses, occupational therapists, or other health professionals providing care for a mental health problem. Specialty mental health sector providers included psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, social workers, or other mental health professionals seen in a mental health setting. Although no validity or reliability data are available, these measures were adapted from measures used in the NCS ( 22 , 23 ) and were included as core measures in all of the CPES instruments.

To characterize quality of depression treatment, we conceptually drew on the Institute of Medicine ( 24 ) definition of quality of care: "the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge" ( 25 ). Assessment of quality of depression care was derived from respondents' reports of past-year service use ( 26 ). Quality of treatment for acute depression was defined according to Wang and colleagues' ( 26 ) use of a binary variable, with a score of 1, indicating adequate treatment, assigned if a patient had four or more specialty or general health provider visits in the past year plus antidepressant use for 30 days or more or if the patient had eight or more specialty mental health provider visits in the past year lasting at least 30 minutes. This measure of quality has also been used extensively in other studies of health disparities ( 27 , 28 , 29 ). In sensitivity analyses, we recognized that some respondents in different stages of the course of their illness may have been appropriately receiving maintenance care, so we considered an alternative, broader quality indicator of four or more mental health visits in the past year with any type of formal provider.

Statistical analyses

We used a two-stage regression model; the first stage estimated correlates of access to any mental health treatment in the past year, and the second estimated correlates of quality depression treatment in the past year for those who had received any mental health care. We estimated a short specification of this model, with adjustments only for need and correlates of need classified in the literature on racial and ethnic disparities. Adjustments were made for age and sex ( 6 , 30 ), number of chronic conditions, and level of impairment. We also estimated an extended specification of the model, which added adjustments for marital status, education, insurance, poverty, and region. The poverty measure was constructed through an income-to-needs ratio according to the definition provided by the U.S. Census Bureau ( 31 ). When household income was less than family needs (determined by family size and household income specified in the Census definition), a family was considered to be in poverty. To emphasize the resource allocation issue, we present odds ratios (ORs) that distinguish between ethnic and racial differences among those with depression and ethnic and racial differences among those without depression.

Next, results from the extended specification were used to estimate the total disparity in accessing care and receiving quality care for each minority group compared with non-Latino whites. Using the two-stage model estimates and the distribution of covariates from the white population, we generated predicted probabilities of accessing treatment and receiving quality treatment for each racial-ethnic and depression subgroup. This approach allowed us to answer the hypothetical question: what level of treatment would persons in this minority group receive if they had the same characteristics as non-Latino whites? McGuire and colleagues ( 30 ) used a similar approach to compute racial and ethnic disparities in outpatient mental health expenditures. In our study, minority individuals were given the non-Latino white distribution for all covariates. We adjusted for variables associated with social class, such as poverty, insurance coverage, and education, to disentangle the effect of social class variables from those of ethnicity and race.

We used the bootstrap method to obtain 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in predicting probabilities of disparity in depression care between each racial and ethnic group and the non-Latino white group. For example, we predicted the treatment that Latinos with depression would receive if they had the same distribution of covariates as non-Latino whites with depression. ( 32 ). All analyses were conducted with Stata 9.2 statistical software ( 33 ). Models were adjusted for sampling design through a first-order Taylor series approximation, and significance tests were performed with design-adjusted Wald tests ( 34 , 35 , 36 ).

Results

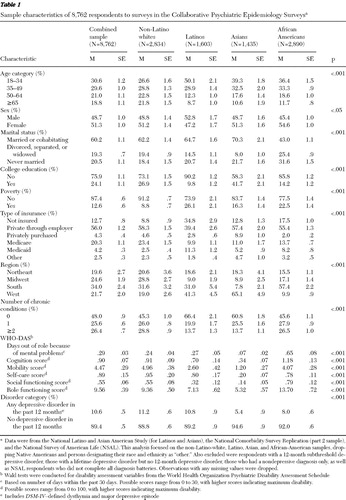

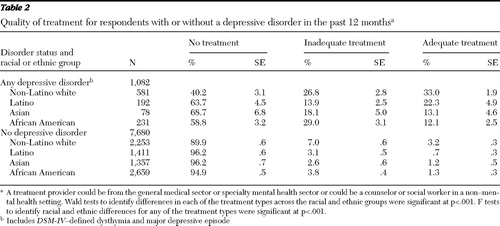

Table 1 shows that there were striking racial and ethnic differences in sample characteristics, including much higher rates of poverty and lower rates of health insurance coverage among all racial and ethnic minority groups compared with non-Latino whites. Latinos and Asians were much more likely than non-Latino whites and African Americans to live in the West, and African Americans were more likely than other groups to live in the South. Current depression was more prevalent among non-Latino whites compared with persons in racial and ethnic minority groups. For example, the prevalence of past-year depressive disorders was 5.4% for Asians and 11.2% for non-Latino whites. Table 2 shows that among those with any depressive disorder in the past 12 months, 63.7% of Latinos, 68.7% of Asians, and 58.8% of African Americans, compared with 40.2% of non-Latino whites, did not access any mental health treatment in the past year (p<.001). Among respondents with depression, those in minority groups also were significantly less likely than non-Latino whites to have received adequate care in the past year (p<.001) ( Table 2 ). Although, as would be expected, most individuals without depression received no treatment, 3.2% of non-Latino whites without past-year depression (or lifetime or subthreshold depression) made four or more provider visits and received 30 days or more of antidepressant treatment, which compares with .7% of Latinos, 1.2% of Asians, and 1.3% of African Americans (p<.001) ( Table 2 ).

|

|

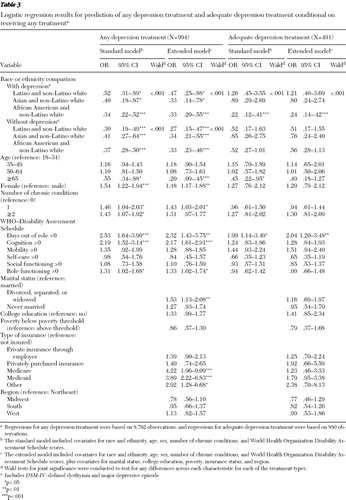

All minority groups with 12-month depressive disorder were significantly less likely than non-Latino whites to receive any mental health care, after analyses adjusted for other factors ( Table 3 ). Similarly, after adjustment for other factors, racial or ethnic minority individuals without depression were less likely than non-Latino whites without depression to receive any treatment. In sensitivity analyses, in which we included the subthreshold depression data and classified these respondents as having depression, the findings were very similar to those discussed here (results not shown).

|

Among those with depression who accessed any care, we found that although there were statistically significant racial and ethnic differences in the quality of care as a whole, only the difference between African Americans and non-Latino whites was statistically significant ( Table 3 ). That is, African Americans who used services in the prior year had appreciably lower odds of receiving adequate depression care compared with whites (OR=.24, 95% CI=14–.42). In two alternative sensitivity analyses, these models were reestimated independent of antidepressant medication with the inclusion of the subthreshold cases and with the looser definition of quality of depression care—the indicator of whether respondents received at least four visits with any formal mental health provider in the past year. The findings were similar to the others. Estimates based on analyses of specific racial and ethnic subsamples rather than a pooled sample yielded similar findings (not shown).

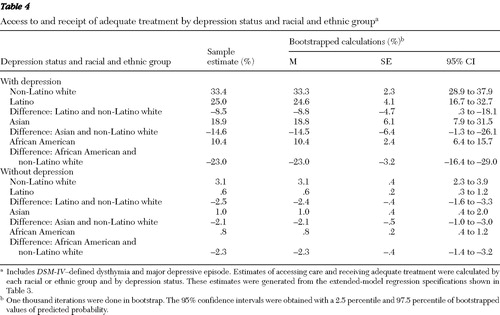

Table 4 shows racial and ethnic differences in predicted probabilities of accessing treatment and receiving adequate treatment for depression based on the extended model for each racial-ethnic subgroup and depression subgroup, if every minority group had the same distribution of covariates as the non-Latino whites. Among non-Latino whites with depression, 33.4% were predicted to access treatment and receive adequate depression care, compared with 25.0% of Latinos, 18.9% of Asians, and 10.4% of African Americans (significantly different for Asians and African Americans at p<.05 and marginally significant for Latinos at p<.07). Among those without depression, 3.1% of non-Latino whites were predicted to access treatment and receive adequate treatment for acute depression; the predicted rates were much lower among racial and ethnic minority groups ( Table 4 ). Latinos, Asians, and African Americans with depression were on average nine to 23 percentage points less likely to access mental health treatment and receive adequate depression treatment than non-Latino whites with similar observed characteristics.

|

Discussion

The results of these analyses highlight that disparities in access to and quality of care for ethnic and racial minority populations remain a critical issue in mental health care. All racial and ethnic minority groups were significantly less likely than non-Latino whites to receive access to any mental health treatment. The observed findings reflect that ethnicity and race, even after adjustment for social class-related variables, such as poverty, insurance coverage, and education, still had an independent effect on access to depression treatment. Several factors could account for the problem in access for persons with minority status. First, there was significant underdetection of depression among the less acculturated ethnic and racial minority groups ( 21 ). Current approaches that rely on providers to detect depression to facilitate its care may have limited effectiveness, given that most respondents (85%–90%) belonging to ethnic and racial minority groups had recent contact with the health care system in the past year but a majority still did not receive treatment for depression.

Helping clinicians identify depression for groups with these particular characteristics might be challenging. Data indicate that symptom presentation for mental health disorders varies across racial and ethnic groups and can differ from what most clinicians are trained to expect, resulting in clinical misdiagnoses ( 37 ). For example, Latinos are more likely to somatize psychiatric distress or to express psychiatric illness through cultural idioms of distress such as ataques de nervios ( 38 ). Second, losing pay from work ( 39 ) or the stigma that surrounds mental illness ( 40 ) may constrain service utilization in racial and ethnic minority communities that are subject to unstable and temporary employment and that are overrepresented in low-wage jobs ( 41 ). For example, people of ethnic and racial minority groups have reported delays in seeking services because of inability to leave work or take time off from work because of lack of benefits ( 29 ). Third, an important factor discouraging minority members from accessing mental health services was their experience of mistreatment by mental health professionals ( 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ). For African Americans, Asians, and Latinos, mistrust of health care professionals and concerns about provider competence with their ethnic-racial group may decrease their sense of comfort in talking to professionals ( 31 , 32 , 33 ). Fourth, minority families appear less likely to recognize depression ( 46 ) or may feel that they can adequately provide care without formal providers ( 47 ). An individual with a mental illness and in a racial or ethnic minority group may be referred into mental health care only when the burden to the family creates undue stress and disruption. Patterns of differences in referral and treatment by providers have also been posited as a potential mechanism for such access disparities ( 48 ). Fifth, a limited workforce and insufficient funds result in inadequate support for mental health services in safety net settings ( 49 ). The Institute of Medicine committee defines the health care safety net as "those providers that organize and deliver a significant level of health care and other related services to uninsured, Medicaid, and other vulnerable patients." ( 50 ).

We also found that regardless of race or ethnicity, most people who accessed depression treatment received inadequate care, with African Americans being particularly unlikely to receive adequate care. This finding can be explained by qualitative analyses of responses of black community members that revealed that their experience of mistreatment and social exclusion by health professionals reverberated on future utilization and on community sentiments toward the mental health system ( 42 ). Disparities resulting from barriers to effective communication between racially mismatched patients and providers, particularly for African Americans, may be leading to greater discordance regarding a shared understanding of disease causation and effectiveness of treatments ( 51 ) and consequently substantial concerns about pharmacological treatments, thereby exacerbating unmet need among African Americans.

There are certain limitations of this study. The cross-sectional nature of the design does not permit us to identify possible causal directions of the findings. The diagnostic and service utilization data are based on self-reports, which may be subject to incomplete information, particularly if patients did not know whether they were being prescribed an antidepressant. Persons from ethnic and racial minority populations, because they are less likely to discuss their treatment with their provider, may be unaware that they are being treated for depression ( 24 ). A further limitation is that no psychometric data are available for the access or quality measures used in this study. However, as mentioned above, these measures were adopted from the NCS ( 22 , 23 ) and have been widely used in mental health services research. As a result, they were included as core measures in the CPES instruments. Regardless, studies assessing the psychometric properties of these measures are needed. Another limitation of this study is that the data in the racial category "other" could not be disaggregated by ethnic subgroup or by geographic location of cities because of small samples. Only certain minority groups were included in the study, but these were better defined and were represented by larger samples than is the case in most national studies. Finally, after we adjusted the characteristics of the minority groups to be the same as those of the non-Latino white population, the disparity estimates were strongly model based, and therefore a different model might lead to a different estimate. Future studies will permit more fine-grained analyses of the factors linked to these disparities. Regardless of these limitations, the findings paint a stark, recent picture of care for depression among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States and clearly point to areas in need of further sustained attention.

An important area for further research includes understanding what "depression treatments" represent when received by non-Latino whites without apparent depression or other measured mental disorders. This pattern could represent treatment for social problems or general psychological distress, overuse of depression treatments, or appropriate use of antidepressant medications for other medical conditions, such as fibromyalgia, painful diabetic neuropathy, migraines, and chronic back pain ( 52 , 53 , 54 ). To the extent that the supply of depression treatments is limited, it may be important to consider how to best distribute those resources across populations that differ in access to quality services, especially for sicker individuals. Future research could evaluate whether use of mental health services by those with no assessed need for care competes with access to treatment for patients in minority groups, possibly limiting their access to mental health providers.

Conclusions

Our findings shift the debate to developing policy, practice, and community solutions to address the barriers that generate these disparities. Simply relying on current systems, without considering the unique barriers to high-quality care that apply for underserved ethnic and racial minority populations, is unlikely to affect the pattern of disparities we observed. For example, populations that have been reluctant to come to the clinic for depression care may have correctly anticipated the limited benefits of usual care. One possible point of intervention is the use of quality improvement programs to increase quality of care among minority groups. Results from a randomized clinical trial demonstrated that a practice-initiated quality improvement intervention for primary care patients with depression improved the rate of appropriate care for depression for whites and underserved minorities alike ( 28 , 55 ). Programs such as this one provide plausible strategies for combating disparities in depression care. Policy changes might include increased resources for mental health services in safety net clinics. Practice changes might include training nurses in motivational interviewing or in routinely implementing evidence-based quality improvement programs for depression. Community strategies might include home visits by peer counselors to engage patients in understanding the importance of treatment or ancillary services (such as transportation, child care, and patient advocacy) that facilitate access to care. Future research should focus on developing and evaluating the promise of such strategies.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The data analysis conducted for this article was made possible by grant K23-DA018715-01A2 from the research division of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The National Latino and Asian American Study data used in this analysis were provided by the Center for Multicultural Mental Health Research at the Cambridge Health Alliance. The project was supported by grant U01-MH-06220 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). This publication was also made possible by grant P50-MH-073469-02 from NIMH. The National Survey of American Life is supported by NIMH grant U01-MH-57716 with supplemental support from the National Institutes of Health Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research and from the University of Michigan. The National Comorbidity Study Replication is supported by grant U01-MH60220 from NIMH, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, grant 044708 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the John W. Alden Trust.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

2. Blanco C, Patel S, Liu L, et al: National trends in ethnic disparities in mental health care. Medical Care 45:1012–1019, 2007Google Scholar

3. Asch S, McGlynn E, Hogan M, et al: Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Annals of Internal Medicine 141:938–945, 2004Google Scholar

4. Kilbourne A, Bauer M, Han X, et al: Racial differences in the treatment of veterans with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 56: 1549–1555, 2006Google Scholar

5. Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, et al: Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:2027–2032, 2001Google Scholar

6. Cook B, McGuire T, Miranda J: Measuring trends in mental health care disparities, 2000–2004. Psychiatric Services 58:1533–1539, 2007Google Scholar

7. Heeringa SG, Berglund P: National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Survey Program (CPES) Data Set: Integrated Weights and Sampling Error Codes for Design-Based Analysis. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan, Survey Research Center, June 4, 2007. Available at www.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/cpes/using.xml?Section=WeightingGoogle Scholar

8. Alegria M, Frank R, McGuire T: Managed care and systems cost- effectiveness treatement for depression. Medical Care 43:1225–1233, 2005Google Scholar

9. Frank R, McGuire T, Normand S, et al: The value of mental health care at the system level: the case of treating depression. Health Affairs 18:71–87, 1999Google Scholar

10. Alegría M, Takeuchi D, Canino G, et al: Considering context, place and culture: the National Latino and Asian American Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:208–220, 2004Google Scholar

11. Kessler R, Merikangas K: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:60–68, 2004Google Scholar

12. Jackson J, Torres M, Caldwell C, et al: The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:196–207, 2004Google Scholar

13. Hartley H: Multiple frame surveys, in Proceedings of Social Statistics Section, American Statistical Association. Alexandria, Va, American Statistical Association, 1962Google Scholar

14. Hartley H: Multiple frame methodology and selected applications. Sankhya Series C 36: 99–118, 1974Google Scholar

15. Colpe L, Merikangas KR, Cuthbert B, et al: Guest editorial. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:193–194, 2004Google Scholar

16. Heeringa S, Wagner J, Torres M, et al: Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:221–240, 2004Google Scholar

17. Duan N, Alegría M, Canino G, et al: Survey conditioning in self-reported mental health service use: randomized comparison of alternative instrument formats. Health Services Research 42:890–907, 2007Google Scholar

18. Neighbors H, Caldwell C, Williams D, et al: Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: results from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). Archives of General Psychiatry 64:1–10, 2007Google Scholar

19. Kessler RC, Ustun TB: The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:93–121, 2004Google Scholar

20. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0, 9/98 revision). New York, New York State Research Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1998Google Scholar

21. Rehm J, Ustun T, Saxena S, et al: On the development and psychometric testing of the WHO screening instrument to assess disablement in the general population. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 8:110–123, 1999Google Scholar

22. Elhai J, Ford J: Correlates of mental health service use intensity in the National Comorbidity Survey and National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychiatric Services 58: 1108–1115, 2007Google Scholar

23. Kessler R, Zhao S, Katz S, et al: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:115–123, 1999Google Scholar

24. Institute of Medicine: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2002Google Scholar

25. Lohr K: Institute of Medicine activities related to the development of practical guidelines. Journal of Dental Education 54:699–704, 1990Google Scholar

26. Wang P, Berglund P, Kessler R: Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:284–292, 2000Google Scholar

27. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 279:1026–1031, 1995Google Scholar

28. Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaumm M, et al: Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:212–220, 2000Google Scholar

29. HEDIS 3.0: Narrative: What's in It and Why It Matters. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 1997Google Scholar

30. McGuire T, Alegría M, Cook B, et al: Implementing the Institute of Medicine definition of disparities: an application to mental health care. Health Services Research 41:1979–2005, 2006Google Scholar

31. Poverty in the United States, 2001, vol 2006. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2002Google Scholar

32. Efron B, Tibshirani R: An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York, Chapman and Hall, 1993Google Scholar

33. Stata Statistical Software Release 9.2. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2007Google Scholar

34. Lin DY: On fitting Cox's proportional hazards models to survey data. Biometrika 87:37–47, 2000Google Scholar

35. Binder DA: Fitting Cox's proportional hazards models from survey data. Biometrika 79:139–147, 1992Google Scholar

36. Schenker N, Gentleman J: On judging the significance of differences by examining the overlap between confidence intervals. American Statistician 55:182–186, 2001Google Scholar

37. Alegría M, McGuire T: Rethinking a universalist framework in the psychiatric symptom-disorder relationship. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44:257–274, 2003Google Scholar

38. Guarnaccia PJ, Martinez I, Ramirez R, et al: Are ataques de nervios in Puerto Rican children associated with psychiatric disorder? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44:1184–1192, 2005Google Scholar

39. Ojeda VD, McGuire TG: Gender and racial/ethnic difference in use of outpatient mental health and substance use services by depressed adults. Psychiatric Quarterly 77: 211–222, 2006Google Scholar

40. Schraufnagel T, Wagner A, Miranda J, et al: Treating minority patients with depression and anxiety: what does the evidence tell us? General Hospital Psychiatry 28:27–36, 2006Google Scholar

41. Diamant AL, Hays RD, Morales LS, et al: Delays and unmet need for health care among adult primary care patients in a restructured urban public health system. American Journal of Public Health 94:783–789, 2004Google Scholar

42. Mclean C, Campbell C, Cornish F: African-Caribbean interactions with mental health services in the UK: experiences and expectations of exclusion as (re)productive of health inequalities. Social Science and Medicine 56:657–669, 2003Google Scholar

43. Echeverry JJ: Treatment barriers accessing and accepting professional help, in Psychological Interventions and Research With Latino Populations. Edited by Garcia JG, Zea MC. Needham Heights, Mass, Allyn and Bacon, 1997Google Scholar

44. Whaley AL: Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African Americans: a review and meta-analysis. Counseling Psychologist 29:513–531, 2001Google Scholar

45. Whaley AL: Cultural mistrust of white mental health clinicians among African Americans with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 71:252–256, 2001Google Scholar

46. Roberts RE, Alegría M, Ramsay RC, et al: Mental health problems of adolescents as reported by their caregivers: a comparison of European, African and Latino Americans. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 32:1–13, 2005Google Scholar

47. Pescosolido B, Wright E, Alegría M, et al: Social networks and patterns of use among the poor with mental health problems in Puerto Rico. Medical Care 36:1057–1072, 1998Google Scholar

48. Bloche M: Race and discretion in American medicine. Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law and Ethics 1:95–131, 2001Google Scholar

49. Vega W, Lopez S: Priority issues in Latino mental health services research. Mental Health Services Research 3:189–200, 2001Google Scholar

50. Lewin ME, Altman S (eds): America's Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Changing Market, Managed Care, and the Future Viability of Safety Net Providers, 2000Google Scholar

51. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo J, Gonzales J, et al: Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA 282:583–589, 1999Google Scholar

52. Chong M, Hester J: Diabetic painful neuropathy: current and future treatment options. Drugs 67:569–585, 2007Google Scholar

53. Wong M, Chung J, Wong T: Effects of treatments for symptoms of painful diabetic neuropathy: systematic review. British Medical Journal 335:87, 2007 E PubGoogle Scholar

54. Atkinson J, Slater M, Capparelli E, et al: Efficacy of noradrenergic and serotonergic antidepressants in chronic back pain: a preliminary concentration-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 27:135–142, 2007Google Scholar

55. Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al: Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research 38:613–630, 2003Google Scholar