Datapoints: Rates and Patterns of Treatment Seeking by Individuals With Mood and Anxiety Disorders

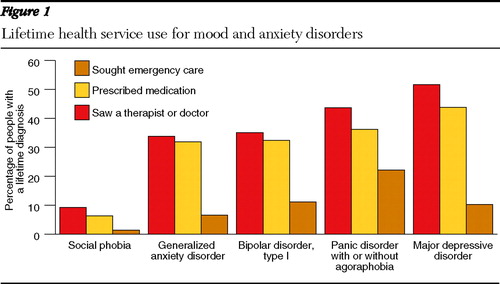

Although epidemiological studies have suggested that only a minority of people with a diagnosable mental illness utilize mental health treatments ( 1 ), the type and venue of treatment received by individuals with a mood or anxiety disorder have received little investigation. The goal of this study was to compare the rates of use of medical services among community-dwelling individuals who met criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder type I. Specifically, we evaluated rates of contact with a therapist or physician, medication usage for a diagnosed mood or anxiety disorder, and use of emergency services.

Data on lifetime psychiatric diagnoses and health service utilization were derived from the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, an epidemiological survey of 43,093 community-dwelling Americans age 18 and older conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). The NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Edition (AUDADIS-IV) was used to generate psychiatric diagnoses. Individuals who met criteria for a lifetime psychiatric diagnosis based on AUDADIS-IV were then asked whether they ever went to a counselor, therapist, or physician; went to the emergency room; and were prescribed medications for the diagnosis in question.

Most people in the community with a lifetime diagnosis of a mood or anxiety disorder did not receive treatment from a physician, therapist, or counselor ( Figure 1 ). Although slightly more than half of those who met criteria for major depressive disorder saw a professional for their mood disorder, only a third of those with bipolar disorder type I received treatment. As a group, lower rates of treatment were reported by individuals with anxiety disorders, compared with those with mood disorders. Of individuals who were seen by a health professional, most reported receiving medication at some point for their condition. A significant minority (22%) of individuals with panic disorder reported seeking emergency services for their condition, double the rate of those with a mood disorder.

In an era of multiple evidence-based psychological and pharmacological treatments for mood and anxiety disorders, most individuals do not receive treatment, with higher rates of nontreatment for anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder type I, compared with major depressive disorder.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar