A Typology of Advance Statements in Mental Health Care

The aim of advance statements regarding mental health care is to give patients more influence over future treatment decisions, thus reducing the occurrence of coerced treatment. Theoretically possible types of advance statements have been delineated ( 1 ), but existing interventions have not been reviewed and compared. The aims of this review are to describe the main dimensions along which existing advance statements vary; to provide a background of the policy and service context in which each type of advance statement has developed; to compare each with respect to research evidence, estimated potential value, and barriers to implementation; to examine their compatibility or conflict with the practice of involuntary treatment, particularly in the community; and to consider the extent to which these statements may coexist with each other.

Overview

Terminology

We use the term "advance directive" to refer to a legal document with statutory authority for individuals to use in planning their own future health care; this term has the most currency in the United States. There has been a shift in the United Kingdom to the use of the term "advance statement" to describe stated preferences for care both in the context of legislation for such statements—for example, the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003—and in its absence ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). As the broadest term, we use it to encompass all vehicles for preference statements covered in this review. The term "advance agreement," introduced by the English Mental Health Act Legislation Scoping Review Study Committee ( 7 ), is used to describe a plan of care agreed between a patient and his or her health providers. The joint crisis plan is one example of this.

Policy contexts

Before describing the types of advance statements that have been developed, we briefly outline the differing policy and legislative contexts in which these have occurred. These contexts have influenced the forms that advance statements have assumed.

In the United States, the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1991 followed legislation for medical advance directives and opened the way for psychiatric advance directives. Under this act, any hospital receiving federal funds (this encompasses Medicaid, Medicare, and the Veterans Health Administration) must notify admitted patients of their right to make an advance directive, inquire whether patients have advance directives, adopt written policies to implement advance directives under state law, and notify patients of what those policies are. All U.S. states permit competent adults to use generic health care decisions laws to make at least some psychiatric treatment choices in advance, typically through the use of a durable power of attorney ( 8 ). Additionally, 25 states since the early 1990s have enacted specific psychiatric advance directive statutes ( 9 ).

The introduction of psychiatric advance directives is potentially one of the most significant recent developments in U.S. mental health law and policy. These directives are intended to provide an opportunity for persons with severe mental illness to retain control over their own treatment during times when they are incapacitated. However, in the new statutes, clinicians are not required to follow directives that conflict with community practice standards, that conflict with need for emergency care, or that are unfeasible or if the patient meets involuntary commitment criteria ( 10 , 11 ).

Specific features of psychiatric advance directive laws vary considerably by state, although there are some commonalities. Most statutes include detailed checklist forms to help consumers prepare psychiatric advance directives. These forms address choices about medications, admission to a mental health care facility, and specific treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy; address the provision of information, such as illness history, medical conditions, drug allergies, and adverse effects; and detail who may be contacted during an emergency. The documents may stand alone or may be used in conjunction with a health care power of attorney and typically must be signed by two witnesses.

Psychiatric advance directives may include a "Ulysses contract" ( 12 )—that is, a request that care or treatment be given during a future period of incapacity, even over the possible later objection or resistance of the person during a crisis. Although clinicians tend to favor this function, consumers are much less supportive ( 13 ). Critics have argued that by ignoring a patient's current stated preferences in favor of a previously documented statement, a Ulysses contract may violate individual liberty and the ethical principle of respect for persons. It follows that a psychiatric advance directive should not result in a person's preferences being ignored when these are stated during episodes of acute mental illness. For this reason, two newer statutes, for Washington State and New Jersey, provide the option of making the psychiatric advance directive (or parts of it) revocable during a crisis, regardless of whether the patient is competent during the crisis. How this would work in practice has not yet been studied.

In the United Kingdom, Scotland has pursued a different policy and legislative path from that taken by England and Wales.

In Scotland, parliament included advance statements in recent mental health legislation—that is, the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003. The written statement must be signed in the presence of a witness, who certifies that the person has the capacity to intend the wishes stated. It can be withdrawn when the person has the capacity to do so, using a document that again has to be signed in the presence of a witness. Under the act, treatment may be given that conflicts with the wishes expressed in the advance statement. If this occurs, the responsible clinician under the act must provide the reasons in writing to the person concerned, the named person under the act, the guardian, the welfare attorney, and the Mental Welfare Commission, as well as place a copy in the person's medical records.

In England and Wales, on the other hand, advance statements have been recognized under "common law" for some years, and their place has now been defined in statute in the Mental Capacity Act 2005. It has been made clear that in the case of mental disorders, mental health legislation (currently the Mental Health Act 1983) takes precedence over any provisions in the Mental Capacity Act. Advance statements can thus be overridden. Since 1999 there has been a process aimed at reforming the Mental Health Act, culminating in Parliament's passing the Mental Health Bill (2006) to amend the Mental Health Act 1983. There was much support for a definition of impaired decision making and for the provision for advance statements to be invoked during a period of impaired decision making in the new legislation, for example, from the Mental Health Act Scoping Review Committee (1999) ( 7 ), a Joint Parliamentary Scrutiny Committee (2005) ( 14 ), the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2006) ( 15 ), and the Mental Health Alliance, an association of nearly all stakeholder organizations involved in mental health treatment. However, this was repeatedly rejected by the government. Concern over public protection outweighed concerns about patient autonomy. Advance statements have therefore taken an essentially clinical form, independent of a statutory basis.

In Germany, Austria, and Switzerland advance agreements (Behandlungsvereinbarungen, which translates as "treatment agreements") are routinely offered in at least 50 hospitals, according to a Web search ( 16 ). (For an example see www.uniklinikum-giessen.de/psychiat/infopatienten/vereinbarung.html.) They were first developed in the late 1980s by service users' initiatives. Common features are requests for treatment in a particular hospital or ward; requests for treatments that were helpful in the past or directives about those that should not be used; preferences for staff gender and emergency measures (forced medication versus physical restraint); nomination of the person to be consulted on decisions about treatment; and arrangements for dependents during hospital treatment.

Behandlungsvereinbarungen are seen as legally binding, but it is acknowledged that a service user's wishes at the time of hospital treatment would normally override a previous agreement. Patients' wishes can be overridden by court-ordered treatment. We are not aware of any cases where Behandlungsvereinbarungen were tested in court. In the absence of any national policies, implementation depends on local initiatives and locally agreed procedures between users and service providers. Little research has been conducted on Behandlungsvereinbarungen; however, most authors regard them as useful tools in empowering service users and reducing coercion ( 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ).

In Germany, psychiatric advance directives (Patientenverfügung or Patiententestament; for an example see www.promentesana.ch/pdf/pati entenverfuegung.pdf) can be centrally registered at www.vorsorgereg ister.de/home.html. Consumers and hospital psychiatrists consider them legally binding ( 21 ). However, the decision regarding hospital commitment remains a matter for the courts. There is case law on involuntary commitment and treatment for people who have made advance directives, but a clear direction is not yet visible. In Austria, a new law on advance directives came into effect in June 2006 (Patientenverfügungsgesetz BGBl Nr.55 8.5.2006, de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patientenverf%C3%BCgungsgesetz).

Comprehensive information about the content and consequences of the directive must be provided before it is signed. It becomes invalid if withdrawn by the patient (it is not a Ulysses contract) or if five years pass without renewal. It is centrally registered and included in the patient's medical record; however, emergency treatment is possible during the time it takes to locate it. The law is directed at end-of-life decisions and makes no reference to psychiatric illness. It remains to be seen how many users of mental health services will make use of it.

Descriptions of advance statements

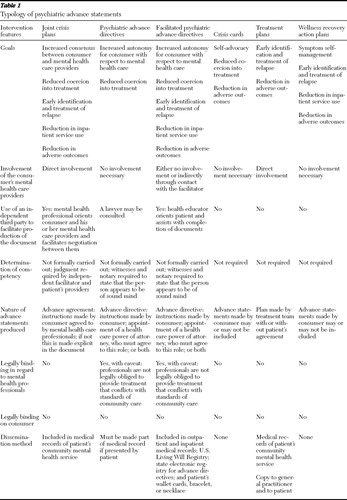

A comparison among the different types described is shown in Table 1 .

|

Psychiatric advance directives

These legal instruments typically offer three ways for a competent individual to plan his or her health care in anticipation of a later time of decisional incapacity. The first way is by providing informed consent to future treatment. The second is by stating personal values and general preferences to guide future health care decisions. The third is by entrusting someone to act as a proxy decision maker for future treatment. Cutting across these types are two types of functions: proscriptive, to opt out of specific forms of treatment, and prescriptive, to opt into treatment ( 1 , 22 ). Content analysis of psychiatric advance directives ( 23 , 24 ) shows that they typically combine both functions, but no participant refused all medications or treatment. Research on their effectiveness at reaching their stated goals ( Table 1 ) is limited to the United States, although professionals' views have been sought on them in Austria ( 25 ).

Facilitated psychiatric advance directives

Facilitated psychiatric advance directives ( 23 ) are a manualized research intervention, the aim of which is to implement psychiatric advance directives effectively in routine clinical settings. A health educator or social worker assists the patient in producing a valid directive, consulting with the patient's clinicians if the patient requests. It is then widely disseminated to maximize its chances of use. One-month follow-up data ( 23 ) are available from a recently completed randomized controlled trial of facilitated psychiatric advance directives. Compared with the control group, the intervention group was far more likely to complete a directive and the contents of the directives were rated by psychiatrists to be consistent with standards of community practice. At one month, participants in the intervention group had a better working alliance with clinicians and reported more frequently that they were receiving the mental health services they needed. This is intriguing given treatment team members' lack of involvement in the intervention. Instead, participants may have had positive experiences during subsequent discussions with providers about the content of their directive.

Crisis cards

In 1989 the United Kingdom's self-advocacy group Survivors Speak Out launched "crisis cards" as an advocacy tool. People who had previously received psychiatric treatment nominated a contact person in the event of a crisis or gave instructions for future psychiatric care in the event that the holder was unable to provide this information verbally. After distributing over 3,000 copies ( 26 ), the group withdrew the card after complaints that professionals were helping patients complete it; this led to fears that patients would be coerced into including potentially damaging content ( 27 ). The Manic Depression Fellowship in the United Kingdom provides a card to its membership of over 4,000, although it is mainly for details of someone to be contacted "in case of need" and does not allow space for treatment preferences. A review of crisis cards and self-help initiatives found no information on their effects during mental health emergencies ( 26 ).

Treatment plans

Treatment plans are a routine component of most community mental health services, and many contain a plan of action to be taken in the event of a crisis or relapse. Policies on treatment planning—for example, the Care Programme Approach in the United Kingdom ( 28 )—usually require that patients be asked to sign the plan and be given a copy. If the patient attends treatment planning meetings and is in accord with the plan's content, it may function as an advance agreement. However, the plan must be completed even if the patient does not attend the treatment planning meeting, and mechanisms do not generally exist to check whether, having been given a copy of the plan, the patient has read and understood it before signing. The extent to which the treatment plan functions as an advance agreement is thus dependent on both the care team and the patient. It would be important to avoid conflict with or confusion between this and an advance statement.

In practice, crisis plans found in treatment plans are often sketchy or nonexistent. A recent audit of Care Programme Approach forms of community mental health team patients attending a hospital emergency department found that only 37 out of 50 (74%) had a crisis plan, and 16 were over six months old (32%) (Nagaiah S, Szmukler G, unpublished report, 2007). Two-thirds of the plans were rated as having good-quality entries regarding relapse indicators, but very few were found to have good-quality information in terms of action to be taken during a crisis, defined as information that was specific to the patient and reflected his or her personal situation and preferences.

Wellness recovery action plan

The wellness recovery action plan is a self-monitoring system designed by Mary Ellen Copeland, Ph.D., and her staff to complement professional care for people who experience psychiatric symptoms ( 29 ). A resource book facilitates its use. To develop a wellness recovery action plan, consumers first identify what helps them stay well. They then list the types of events that may lead to an increase in symptoms, what these symptoms are, and how to respond to them. This is followed by a crisis plan identifying symptoms that indicate that someone should assume responsibility for their care, who this should be, and actions this person should and should not take. Although instructions are given, the crisis plan is not a legal document and therefore has more in common with the crisis cards described above, albeit containing more detail, than with psychiatric advance directives. Without providers' knowledge or input the plan may not be accessible to them; if providers are involved, as now occurs in a number of settings in the United States, it could become an advance agreement, but this requires consensus regarding the content.

No research literature is available on the level of use of the wellness recovery action plan, its effects, or the impact of provider involvement. However, a randomized controlled trial is under way at the University of Illinois at Chicago in which groups of consumers will be taught how to complete the plan (www.cmhsrp.uic.edu/nrtc/wrap.asp).

Joint crisis plans

The joint crisis plan ( 30 ) is so far a research intervention. A third-party facilitator, namely an experienced mental health professional who is not part of the treatment team, takes the lead in ensuring its production. The facilitator convenes a meeting with the patient and case manager to help them begin to formulate the contents under a number of preformatted headings. This prepares the participant for a second meeting held to finalize the content, attended by the mental health professionals involved in the participant's care, including the treating psychiatrist. The participant is encouraged to bring a relative, friend, or advocate. The facilitator's role is to help the parties negotiate either a consensus or an "agreement to differ." For example, if the patient wishes to refuse all medication and the professionals disagree, the facilitator must explore which medications, doses, or routes of administration the patient particularly objects to, so that more specific refusals can be made to which professionals can agree. Where an agreement cannot be made, the facilitator will make this clear on the plan, and the holder is given the option of renaming the document a crisis card to reflect the lack of consensus.

Results of a randomized controlled trial of joint crisis plans ( 31 , 32 ) showed that application of compulsory powers, either involuntary transportation to a place of safety (hospital emergency room or police station) or detention in a psychiatric inpatient facility, was significantly reduced for the intervention group. Further, fewer episodes of violence occurred in the intervention group. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves suggested that there was a greater than 78% probability that joint crisis plans were more cost-effective than the control intervention and routine care in reducing admissions for this group. Although this trial gave limited data regarding the mechanism of action, the results suggest that the joint crisis plan allows providers to manage risk in a way that is more closely based on patient preference, rarely having to override its content through use of the Mental Health Act. A larger multisite trial, the Crisis Plan Impact: Subjective and Objective Coercion and Engagement (CRIMSON) study, is now under way that is funded by the United Kingdom's Medical Research Council.

Key dimensions of variation

Purpose

The above interventions share the goal of preventing adverse consequences of relapse. They use different models to try to achieve this; consequently each has additional goals not shared by the others. Psychiatric advance directives represent the consumer choice model, which prioritizes the goal of autonomy. Treatment plans lie at the paternalistic end of the spectrum, as they may be executed without patient involvement, although by consensus this is not seen as good practice. Their chief goal is to ensure that a plan is made and carried out in order to provide timely and effective care in a coordinated fashion. Joint crisis plans lie toward the center, as an application of the shared decision-making model ( 33 ). Their chief goal is to produce a plan that all can agree to, even if some aspects are not the first choice of the patient or treatment provider. Aspirations related to the chief goal, such as empowerment through illness self-management (wellness recovery action plan) or improved therapeutic alliance through reaching consensus (joint crisis plan), are based on assumptions about mechanisms of action, but at this point we know little about whether each can be used to achieve its goals and even less about any mechanisms.

Whether legally binding

With the exception of Behandlungsvereinbarugen and psychiatric advance directives, advance statements are not considered legally binding. Psychiatric advance directives have to be formally invoked during periods of incapacity, while the others can be more broadly integrated into a plan of treatment. In the United States, health professionals are, with certain caveats, legally obligated to follow psychiatric advance directives. Caveats less open to debate are that psychiatric advance directives may be overridden if the patient meets the state's criteria for involuntary commitment and if the requests made cannot feasibly be followed by care providers. However, the legal terrain remains unsettled on questions of physicians' responsibilities to follow psychiatric advance directives that include instructions to refuse treatment.

The newer psychiatric advance directive statutes typically do not require physicians to follow advance instructions that conflict with community practice standards. However, a 2003 U.S. Court of Appeals decision, Hargrave v. Vermont, struck down a state law that allowed mental health professionals to override Nancy Hargrave's advance refusal of all psychotropic medications through a general health care proxy after commitment to a hospital ( 34 , 35 ). Hargraves's challenge was based on the Americans With Disabilities Act; she claimed that because only committed persons with mental illness could have their advance directive overridden, she was being discriminated against in that she was being excluded on this basis from a public "service, program, or activity"—that is, the durable power of attorney she had completed.

Hargrave means that even persons committed to a mental health care facility cannot be forcibly treated with medication, if medication was refused in a competently prepared advance directive. This decision highlights the need to ensure that consumers are aware of the consequences of their instructions—that is, that they have the capacity to complete psychiatric advance directives. Concern has been expressed that the court decision will make clinicians reluctant to encourage the use of these legal instruments ( 34 , 35 ). On the other hand, perhaps it will promote dialogue with those who wish to refuse everything currently available and will encourage the development of forms of care and treatment more acceptable to them.

Service provider involvement

With few exceptions, statutes covering advance directives do not require provider input in their preparation, although it may be recommended. The joint crisis plan and routine treatment planning are the only interventions in which the patients' usual care providers are integrally involved; however, increasing numbers of nonpsychiatrist providers are helping consumers complete the wellness recovery action plan. Facilitated psychiatric advance directives may involve clinicians indirectly.

Independent facilitation

In the case of facilitated psychiatric advance directives and joint crisis plans, the facilitator's role ensures the implementation of a research intervention but is at the same time an integral aspect of the intervention. A psychiatric advance directive facilitator meets with the patient and, if the patient requests, contacts providers to discuss the directive's content. This maximizes the chances that a valid directive will be completed. The joint crisis plan facilitator is an independent and experienced mental health professional, who brings together the patient and service providers and negotiates content for the plan.

Strengths and weaknesses

Several advance statements have a particular strength, distinguishing them from others. The crisis plan in the wellness recovery action plan is preceded by a detailed self-management system, so that by the time it is completed patients should have given considerable thought to what has helped or not helped in the past. The psychiatric advance directive promotes patient autonomy; as a legal document it states the circumstances where it may be overridden, and legal action may be taken if this is felt by the patient to be unjustified. Further, the use of national- and state-level arrangements makes them electronically accessible to providers. The facilitated psychiatric advance directive enhances these strengths by making completion easier and increasing the chances that the resulting psychiatric advance directive will be both legally valid and clinically feasible.

However, self-completed psychiatric advance directives, wellness recovery action plans, and crisis cards may suffer from lack of provider input. Observations made during relapse, records of medications causing adverse reactions, and knowledge of available services and treatments can help guide people making advance statements. Attendance during production ensures providers' awareness of the statement, increasing its chances of use. There is also an opportunity for an impact on the therapeutic relationship, perhaps in terms of the consumer's trust or the provider's risk perception. On the other hand, provider involvement puts the patient at risk of pressure; hence, Survivors Speak Out withdrew their crisis cards. Because providers are necessarily involved in treatment planning, this entails the risk that discussion of previous experiences and preferences may be curtailed by a paternalistic approach. To ensure that patients are not pressured by providers or informal carers, the psychiatric advance directive facilitator will contact providers if the patient wishes in order to discuss the content of the psychiatric advance directive, whereas the joint crisis plan facilitator works with the providers and the patient together.

Treatment plans currently have the highest chance of completion. They address ongoing and emergency care, as well as interprofessional communication and communication between patient and providers. The extent to which the crisis plan section in a treatment plan is implemented will depend partly on the patient's awareness of and agreement with what is in the plan, which in part will depend on the patient's involvement in creating it. The joint crisis plan ensures this involvement by having the facilitator meet with the patient at least a day before it is finalized (finalizing the plan involves meeting with the patient and psychiatrist together), giving the patient a chance to think about the content without the psychiatrist.

Co-existence with outpatient commitment

In the United States, an estimated 12% to 20% of outpatients in public mental health service systems have experienced outpatient civil commitment or a comparable judicial order to participate in community-based treatment ( 36 ). About half of patients have experienced some type of mandated community treatment, either through the legal system (such as outpatient commitment) or the social welfare system (such as having a representative payee who conditions receipt of money on treatment adherence) ( 37 ). This means, in practice, that as psychiatric advance directives become more common, they will in many cases be completed by consumers who are simultaneously on outpatient commitment or another mandated treatment regime. Swanson and colleagues ( 12 ) have pointed out that both outpatient commitment and psychiatric advance directives aim to reduce involuntary hospitalization while increasing patient involvement in care. However, court-mandated community treatment has fuelled interest in psychiatric advance directives as a reaction in favor of the consumer choice model and against a perceived pervasive paternalistic ideology that critics associate with outpatient commitment ( 12 , 36 ).

In jurisdictions with both psychiatric advance directives and outpatient commitment legislation, such as Scotland and some U.S. states, the question arises as to whether these two legal instruments are compatible with each other. It has perhaps been assumed that outpatient commitment will apply to a small number of individuals with chronic lack of insight into their need for treatment ( 38 ), while psychiatric advance directives may be appropriate for others who are competent to plan ahead for future mental health crises. However, someone meeting the criteria for outpatient commitment might complete a valid psychiatric advance directive.

At least one outpatient commitment statute makes an attempt to incorporate psychiatric advance directives. New York's Mental Hygiene Law 9.60 (also known as Kendra's Law) states that when a person subject to court-ordered treatment has a health care proxy, any advance instructions given to the agent must be considered by the court in determining the written treatment plan. In practice, reconciling the goals of two quite different statutory instruments—one aimed at enhancing autonomy and the other representing a form of coercion—may be very challenging. The use of such forms of coercion tends to increase once the infrastructure exists to deliver them ( 39 , 40 ). Meanwhile, little or nothing has been invested to ensure effective implementation of psychiatric advance directives. There is thus a risk that outpatient commitment may be used with increasing frequency as a way to "resolve" disagreements about care instead of an approach that takes treatment preferences into account.

Co-existence of advance statements

It is not difficult to envisage the co-existence of more than one type of advance statement; indeed, wellness recovery action plans and psychiatric advance directives already do so in the United States, as do treatment agreements and psychiatric advance directives in Germany and Austria. The wellness recovery action plan or the joint crisis plan procedures could be used to complete a psychiatric advance directive. The content of a psychiatric advance directive, joint crisis plan, or wellness recovery action plan could likewise be used to inform the development of a treatment plan. This would minimize the conflict between the treatment plan and any statement of preference that the patient makes, but it would also alert all parties to any existing conflict that cannot be resolved, whether or not this conflict is likely to lead to a consumer's preference being overridden in the future, and what the consequences of overriding a preference could be.

Given the potential choice of advance statements and the possibility of using some in combination, how are consumers to make an informed choice? First, much more information is required on the outcomes associated with each. Second, all need to be made accessible for completion. Third, outcome information should be incorporated into a decision aid that would also elicit consumers' preferences, both broadly in terms of what model of care they are most comfortable with (paternalistic, shared decision making, or consumer choice) and narrowly in terms of other differences among the interventions. For example, do they want it to be legally binding, with the caveats that exist? Do they want it to be formally invoked during periods of incapacity or to be applicable to periods of early relapse? Do they want an aide-memoire for self-management, for a cue for providers to act, or both?

Implementation

Advance statements face two challenges to implementation—completing and honoring—which occur separately but are likely to influence each other. Ideally, the mode of completion should ensure not only that providers are made aware of the statement but also that they agree to honor the preferences expressed; the expectation that this will occur is in turn likely to influence a consumer's decision to complete an advance statement.

The greatest success in completion has been achieved in the context of research ( 5 , 23 ). The trial of the joint crisis plan ( 31 ) suggested that although some plans were not always honored because of access problems or a decision that it was in the patient's best interest not to follow the plan, the intervention did lead to improvement in some outcomes for the group.

Besides research interventions, rates of completion and the barriers to doing so have been best studied with respect to psychiatric advance directives ( 13 , 22 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ). Despite training for consumers and professionals in some U.S. states ( 48 ), their rate of uptake has been low. A recent survey of over 1,000 psychiatric outpatients in five U.S. cities found that only 4% to 13% of consumers had executed one ( 9 ). However, surveys suggest a much higher level of interest than these figures suggest ( 41 , 42 ). Further, clinicians and family members of persons with severe mental illness generally endorse them in concept ( 13 ), although clinicians tend to be concerned about certain aspects of them and how they will work in practice ( 49 ). Some obstacles to meeting this demand include consumers' difficulty in getting the document witnessed and notarized, lack of someone to act as the proxy or surrogate decision maker, or doubts about whether providers would follow the content. Other barriers may be caused by clinicians' resistance, resulting from a lack of awareness of psychiatric advance directives, countervailing practice pressures, legal defensiveness, or discomfort with the notion of consumer-directed care or shared decision making. Still other barriers have to do simply with lack of resources to create and implement psychiatric advance directives in fiscally constrained public systems of care.

For the consumer, having an advance statement be honored is a fundamental outcome in itself and not just an operational issue that may mediate its effectiveness with respect to outcome measures. Giving the document legal status, as in the psychiatric advance directive, and involving the patient's psychiatrist in the process, as in the joint crisis plan, represent two strategies to ensure the content is honored, although both may create barriers to completion, such as consumer reluctance to sign a legal document or psychiatrist reluctance to discuss the content. In the United States legal status may be important because provider discontinuity after a person is hospitalized makes it harder to ensure that an advance statement will be honored. This makes the content all the more important, as it has the potential to be the earliest information inpatient providers receive besides what the patient or relatives provide verbally. Responsibility on the part of psychiatrists for their patients when both in and out of hospital, as for example in the United Kingdom under the National Health Service, is in theory the best existing system to ensure inpatient provider awareness of advance statements. However, the U.K. study of advance directives that did not involve providers ( 5 , 6 ) showed that many providers were unaware of the directives despite having been sent them, suggesting that awareness requires their direct involvement in the process of production.

Ensuring this involvement and using a facilitator makes the joint crisis plan more expensive than either the facilitated psychiatric advance directive or the treatment planning process. However, it may confer advantages over both, because providers are then aware of and have access to a plan that they and the patient have shaped and agreed to, and thus it may be cost-effective relative to treatment planning ( 33 ). In turn, the expectation that having been involved in its production, the provider is more likely to honor it, may lead to higher rates of consumer participation than for statements produced without provider involvement. The potential downside of this situation for the consumer is a loss of autonomy; the challenge that the joint crisis plan is designed to meet is to regulate provider involvement so that the process does not become a paternalistic one. Ultimately, the ideal situation is for consumers to be able to consider the pros and cons of including their providers in making an advance statement, both in terms of their own experience of their providers and research data on the impact of their involvement, and to make an informed choice.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Atkinson JM, Garner HC, Stuart S, et al: The development of potential models of advance directives in mental health care. Journal of Mental Health 12:575–584, 2003Google Scholar

2. Government Response to the Report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Mental Health Bill, 2004. London, Department of Health, The Stationery Office, 2005Google Scholar

3. Thomas P, Cahill AB: Compulsion and psychiatry: the role of advance statements. BMJ 329:122–123, 2004Google Scholar

4. Thomas P: How should advance statements be implemented? British Journal of Psychiatry 182:548–549, 2003Google Scholar

5. Papageorgiou A, King M, Janmohamed A, et al: Advance directives for patients compulsorily admitted to hospital with serious mental illness: randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 181:513–519, 2002Google Scholar

6. Papageorgiou A, Janmohamed A, King M, et al: Advance directives for patients compulsorily admitted to hospital with serious mental disorders: directive content and feedback from patients and professionals. Journal of Mental Health 13:379–388, 2004Google Scholar

7. Draft Outline Proposals: Review of Mental Health Act 1983. London, UK, Scoping Study Committee, 1999Google Scholar

8. Fleischner R: Advance directives for mental health care: an analysis of state statutes. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 4:788–804, 1998Google Scholar

9. Swanson J, Swartz M, Ferron J, et al: Psychiatric advance directives among public mental health consumers in five US cities: prevalence, demand, and correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 34:43–57, 2006Google Scholar

10. Swanson J, McCrary SV, Swartz M, et al: Superseding psychiatric advance directives: ethical and legal considerations. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 34:385–394, 2006Google Scholar

11. Swanson J, McCrary SV, Swartz MS, et al: Overriding psychiatric advance directives: factors associated with psychiatrists' decisions to preempt patients' advance refusal of hospitalization and medication. Law and Human Behavior 31:77–90, 2007Google Scholar

12. Swanson JW, Tepper MC, Backlar P, et al: Psychiatric advance directives: an alternative to coercive treatment? Psychiatry 63:160–172, 2000Google Scholar

13. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Hannon MJ, et al: Psychiatric advance directives: a survey of persons with schizophrenia, family members, and treatments providers. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 2:73–86, 2003Google Scholar

14. House of Lords and House of Commons Joint Committee on the Draft Mental Health Bill. Draft Mental Health Bill: Session 2004–05, Vol 1. London, Stationery Office, 2005Google Scholar

15. Briefing on the Mental Health Bill 2006. London, Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2006Google Scholar

16. Zinkler M, Amering M, Stastny P, et al: Advance directives and advance agreements. British Journal of Psychiatry 187:388–389, 2005Google Scholar

17. Dietz A, Pörksen N, Voelzke W: Treatment Agreements: Confidence-Building Measures in Acute Psychiatry [in German]. Bonn, Psychiatrieverlag, 1998Google Scholar

18. Dietz A, Hildebrandt B, Pleininger-Hoffmann M, et al: Treatment agreements in acute psychiatry [in German]. Recht und Psychiatrie 20:27–32, 2002Google Scholar

19. Rittmannsberger H, Lindner H: First experiences with the offer of treatment agreement [in German]. Psychiatrische Praxis 33:98, 2006Google Scholar

20. Zinkler M: Preventive treatment versus treatment agreement and advance directive [in German]. Recht und Psychiatrie 18:165–167, 2000Google Scholar

21. Lehmann P: Theory and practice of the psychiatric will: timely precautions to turn away forced treatment and to defend human rights. Abstracts of the World Congress of the World Federation for Mental Health, Lahti, Finland, July 6–11, 1997Google Scholar

22. Atkinson JM, Garner HC, Gilmour WH: Models of advance directives in mental health care: stakeholder views. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 39:667–672, 2004Google Scholar

23. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, et al: Facilitated psychiatric advance directives: a randomized trial of an intervention to foster advance treatment planning among persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1943–1951, 2006Google Scholar

24. Srebnik DS, Rutherford LT, Peto T, et al: The content and clinical utility of psychiatric advance directives. Psychiatric Services 56:592–598, 2005Google Scholar

25. Amering M, Denk E, Griengl H, et al: Psychiatric wills of mental health professionals: a survey of opinions regarding advance directives in psychiatry. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:30–34, 1999Google Scholar

26. Sutherby K, Szmukler GI: Crisis cards and self-help crisis initiatives. Psychiatric Bulletin 100:4–7, 1998Google Scholar

27. Weston LP, Lawson LA: The mental (corrected) health emergency card. British Medical Journal 314:532–533, 1997Google Scholar

28. Effective Care Co-ordination in Mental Health Services: Modernising the Care Programme Approach. London, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, National Health Service Executive/Social Services Inspectorate, 1999Google Scholar

29. Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery. Available at www.copelandcenter.com/whatiswrap.htmlGoogle Scholar

30. Sutherby K, Szmukler GI, Halpern A, et al: A study of "crisis cards" in a community psychiatric service. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:56–61, 1999Google Scholar

31. Henderson C, Flood C, Leese M, et al: Effect of joint crisis plans on use of compulsory treatment in psychiatry: single blind randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 329:136, 2004Google Scholar

32. Flood C, Byford S, Henderson C, et al: Joint crisis plans for people with psychosis: economic evaluation of a randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 333:729–732, 2006Google Scholar

33. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T: Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science and Medicine 44:681–692, 1997Google Scholar

34. Appelbaum PS: Psychiatric advance directives and the treatment of committed patients. Psychiatric Services 55:751–752, 2004Google Scholar

35. Allen M: Hargrave v Vermont and the quality of care. Psychiatric Services 55:1067, 2004Google Scholar

36. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Kim M, et al: Use of outpatient commitment or related civil court treatment orders in five US communities. Psychiatric Services 57:343–349, 2006Google Scholar

37. Monahan J, Redlich AD, Swanson J, et al: Use of leverage to improve adherence to psychiatric treatment in the community. Psychiatric Services 56:37–44, 2005Google Scholar

38. Lawton-Smith S: Community-Based Compulsory Treatment Orders in Scotland: The Early Evidence. London, Kings Fund, 2006Google Scholar

39. Atkinson JM, Gilmour WH, Dyer J: Retrospective evaluation of extended leave of absence in Scotland 1988–1994. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry 10:139–155, 1999Google Scholar

40. Burgess P, Bindman J, Leese M, et al: Do community treatment orders for mental illness reduce readmission to hospital? An epidemiological study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41:574–579, 2006Google Scholar

41. Backlar P, McFarland BH, Swanson JW, et al: Consumer, provider, and informal caregiver opinions on psychiatric advance directives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 28:427–441, 2001Google Scholar

42. Srebnik DS, Russo J, Sage J, et al: Interest in psychiatric advance directives among high users of crisis services and hospitalization. Psychiatric Services 54:981–986, 2003Google Scholar

43. Amering M, Stastny P, Hopper K: Psychiatric advance directives: qualitative study of informed deliberations by mental health service users. British Journal of Psychiatry 186:247–252, 2005Google Scholar

44. Dorn RA, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, et al: Clinicians' attitudes regarding barriers to the implementation of psychiatric advance directives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 33:1–12, 2006Google Scholar

45. Miller RD: Advance directives for psychiatric treatment: a view from the trenches. Psychology, Public Policy and the Law 4:728–745, 1998Google Scholar

46. Srebnik D, Brodoff L: Implementing psychiatric advance directives: service provider issues and answers. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 30:253–268, 2003Google Scholar

47. Peto T, Srebnik D, Zick E, et al: Support needed to create psychiatric advance directives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 31:409–419, 2004Google Scholar

48. Appelbaum PS: Advance directives for psychiatric treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:983–984, 1991Google Scholar

49. Elbogen EB, Swartz MS, Van DR, et al: Clinical decision making and views about psychiatric advance directives. Psychiatric Services 57:350–355, 2006Google Scholar