Factors Contributing to the Quality of Sibling Relationships for Adults With Schizophrenia

With deinstitutionalization, many individuals with mental illness turned to their families for support because of the absence of adequate community-based services. Even today, with the presence of a greater array of community services, family members, in particular parents, often step in to fill in the gaps in the service system. However, many of these parents are now in their retirement years. Thus growing numbers of adults with schizophrenia will likely look to their siblings for support as their aging parents' capacity to provide care diminishes and ultimately ends ( 1 , 2 ).

The quality of the relationship that individuals with schizophrenia develop with their siblings has great significance for their overall quality of life. The quality of this relationship influences the involvement of siblings in helping their brothers or sisters with mental illness as well as their expectations about their future involvement ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). Also, having a high-quality sibling relationship enhances the life satisfaction of adults with schizophrenia ( 6 ). Yet little is known about factors that sustain bonds of affection between siblings when one sibling has a severe mental illness such as schizophrenia ( 7 ). In this study we examined the factors that affect the quality of the relationship between siblings when one has schizophrenia.

We investigated the predictors of sibling relationship quality from a life course perspective. This approach sensitizes us to how the lives of siblings are linked across time, with earlier life course experiences shaping the quality of current relationships. Research on normative sibling relationships suggests that the quality of adult sibling relationships is strongly influenced by the family environment during childhood. A longitudinal study found that children who grew up in highly cohesive families had closer sibling relationships five years later ( 8 ). Similarly, Pulakos found that undergraduates from more cohesive families reported closer relationships in adulthood ( 9 ).

Gender plays an important role in shaping childhood socialization experiences and, by extension, the quality of the adult sibling relationship. In our culture, women are socialized from an early age to care for others ( 10 ). Sisters are more likely than brothers to provide support and have close ties with their siblings ( 11 , 12 ). Further, researchers examining adult sibling relationships found that sister-sister dyads were closer when compared with brother-brother or brother-sister dyads ( 13 , 14 ).

In addition, the quality of the sibling relationship changes as people age. Literature on typical sibling relationships indicates that siblings have strong ties of affection during childhood and adolescence. However, siblings become more distant during early and middle adulthood because of competing demands from work and family ( 15 ). Yet during late middle and older age, after children are launched from their parents' home, siblings have increased contact and greater intimacy ( 16 ).

A life course perspective draws attention to the interplay of earlier stressful life events on adult development and relationships. Although few individuals with schizophrenia display threatening or violent behaviors, when such behaviors occur, family members are likely to be targets of these acts. It has been estimated that between 10% and 40% of families experience violence from their ill relative's behavior ( 17 ). Estroff and colleagues ( 18 ) reported that among family members who were victims of such behavior, 19% were siblings. Siblings who have felt threatened by their brother or sister with schizophrenia may fear that their siblings will again lose control of their behavior and be a threat to their safety or the safety of their family ( 19 ). Siblings who experience these fears are likely to distance themselves from their sibling with schizophrenia, thus negatively affecting the quality of their relationship.

On the basis of their accumulated experiences, siblings formulate certain beliefs about the nature of their brother's or sister's behavior and symptoms. Because siblings are often poorly informed about mental illness, they may have great difficulty distinguishing between behavior that is intentional and behavior that is the result of the mental illness. Greenley ( 20 ) has argued that in our society, individuals who are appraised as having control over their behavior or illness are viewed as not deserving of help. Feelings of anger and resentment are likely to arise when siblings view their brother or sister with mental illness as having control over disturbing behaviors and symptoms, which would be expected to erode the sibling relationship. Family members report weaker family ties when they appraise their relative as having greater control over his or her symptoms ( 21 ).

A life course perspective also emphasizes the resiliency of individuals and their capacity to grow. There is increasing recognition that family members may experience a variety of personal gains from coping with the stress of mental illness, including an increased awareness of their inner strengths, the development of new skills, and the establishment of new friendships ( 22 ). These positive transformations are likely to increase siblings' capacity for a more positive and mutually supportive relationship with their brother or sister with schizophrenia.

In summary, a life course framework guides our investigation of the factors associated with the quality of the relationship between siblings when one sibling has schizophrenia. We hypothesized that sisters, siblings without children at home, siblings who grew up in highly cohesive families, and those who feel they have grown from the experience of coping with their sibling's mental illness would report a better relationship with their brother or sister with schizophrenia. In contrast, we hypothesized that siblings who report being physically hurt or threatened by their brother or sister with schizophrenia, who express greater fear of him or her, and who believe that he or she has control over symptoms would report a poorer relationship.

Methods

Design and sample

The data come from the third wave of a large-scale longitudinal study of aging families of adults with schizophrenia living in Wisconsin. In the larger study, mothers were the primary respondents and eligible to participate if they were 55 years or older and provided at least weekly assistance to an adult son or daughter with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. At the third wave of the study, 248 mothers participated. In addition, one father and two siblings participated because they had assumed the primary caregiving role as a result of the mother's death or declining health. A sibling substudy was added at the third wave to examine the role of siblings as future caregivers. Of the 249 parents (248 mothers and one father) approached at the third wave, in seven cases the adult with schizophrenia was the only child, and in four cases the "most involved" sibling also had schizophrenia and was not eligible for the sibling study. Of the remaining 238 parents, 28 indicated that none of their other adult children would be involved in the future care of their sibling with schizophrenia, and thus these families were not eligible for the sibling study. For the 210 parents who indicated a sibling would be involved, we described the sibling study and asked permission to contact the most involved (or only) sibling to request his or her permission to participate in a survey distributed by mail.

A total of 191 parents gave permission to contact the sibling. The two siblings who had assumed a primary caregiving role because their parents had died were also invited to participate in the sibling substudy. After the study received approval from an institutional review board, 193 siblings were provided with a complete description of the study and were sent informed consent documents and questionnaires. Of these, 141 siblings returned questionnaires and signed informed consent forms. Five cases were excluded because of missing data on key independent variables.

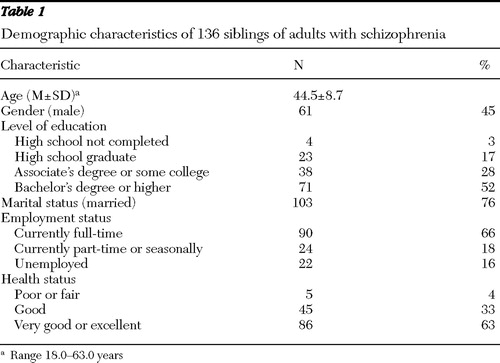

As shown in Table 1 , siblings ranged in age from 18 to 63 years, with a mean±SD age of 44.5±8.7 years, and 75 (55%) were female. Six siblings (4%) were from an ethnic minority group: four siblings (3%) were African American, and two siblings (2%) were nonwhite Hispanic. Seventy-one siblings (52%) graduated from college, with a mean income of $47,500±$12,000. Only 16 siblings (12%) were either present or past members of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

|

Measures

The dependent variable, the quality of the sibling relationship, was measured by the Positive Affect Index ( 23 ). Each item was rated on a 6-point scale (1, not at all; 6, extremely). Five items assessed the sibling's feelings toward the brother or sister with schizophrenia along the dimensions of trust, intimacy, understanding, fairness, and respect. A second set of five similar items assessed the sibling's perception of the ill sibling's feelings toward him or her. The items were summed for a total score. Possible scores ranged from 10 to 60, with higher scores indicating a higher-quality relationship. Overall, siblings reported feeling moderate levels of closeness (42.4±8.8). Cronbach's alpha of reliability was .92.

Turning to the predictors of relationship quality, we measured family cohesion during childhood by the family cohesion subscale of the Family Environment Scale ( 24 ). For each of nine items, respondents indicated whether the statement about closeness in their family during their growing-up years was true. The items were summed for a total score. Possible scores range from 0 to 9, with higher scores representing higher levels of cohesion. The family cohesion subscale had a mean score of 5.9±2.8. Cronbach's alpha of reliability was .85.

Siblings were asked to indicate whether their brother or sister with schizophrenia had ever been physically harmful or threatening. A code of 1 was assigned if the sibling responded affirmatively to either of these two items, and 0 was assigned otherwise. Eleven (8%) siblings reported being struck or injured by their brother or sister with schizophrenia, and 21 (15%) reported being physically threatened.

The fears scale was developed by Greenley ( 25 ) and modified for use with siblings ( 26 ). The scale consists of six items rated on a 4-point scale (0, never; 3, often) and measures a family member's fears related to the unpredictability of the symptoms or behaviors of the relative with mental illness. The items were summed for a total score. Possible scores range from 0 to 18, with a higher score reflecting greater fears. The fears scale had a mean score of 7.5±4.5. Cronbach's alpha of reliability was .89.

On the basis of work by Pearlin ( 27 ), a ten-item scale was adapted to measure personal gains experienced in the process of coping with a relative's mental illness. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale (0, not at all; 3, a great deal) and summed for a total score. Possible scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater personal gains. The mean score of the gains scale was 17.3±7.7. Cronbach's alpha of reliability was .94.

The Control Attributions Scale ( 20 , 28 ) is a five-item scale indicating the respondent's appraisal of the degree to which the adult with schizophrenia has control over his or her symptomatic behavior. The items were rated along a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0, strongly disagree, to 3, strongly agree. Responses were summed and ranged from 0 to 15 for a total score, with higher scores indicating that siblings perceived their brothers or sisters with schizophrenia as having more control over their symptoms. The scale had a mean score of 3.7±3.0. Cronbach's alpha of reliability was .81.

A dichotomous variable was included to indicate the sibling's life stage. If the respondent had children at home, he or she was coded 1; otherwise, the code was 0. Finally, a variable was created to indicate whether the sibling dyad was sister-sister (coded 1) or not (coded 0).

The symptom scale from the Schizophrenia Outcome Module was included to control for the psychiatric symptoms of the adults with schizophrenia ( 29 ). This 11-item instrument measures the frequency of psychiatric symptoms over the past month. The symptoms were reported by the primary caregiver because they were not part of the sibling questionnaire. Each item was scored on a 4-point scale (0, not at all; 3, a great deal) and summed to derive a total score ranging from 0 to 33, with a higher score indicating greater psychiatric symptoms. The symptom scale had a mean score of 9.3±7.1. Cronbach's alpha of reliability was .89.

Multiple regression analysis was used to examine the predictors of the quality of the relationship.

Results

As shown in Table 2 , contrary to our hypothesis, the quality of the relationship was not significantly related to whether the sibling had children at home. Although results were in the hypothesized direction, sister dyads did not show closer relationships than brother dyads or mixed-gender sibling dyads. However, consistent with our hypothesis, siblings who reported growing up in more cohesive families reported a better relationship ( β =.16, p<.05), whereas those who reported that their brothers or sisters with schizophrenia had ever been violent or threatening toward them evaluated their current relationship as poorer ( β =-.18, p<.05). In addition, as hypothesized, siblings who had more fears of their brother's or sister's behavior ( β =-.17, p<.05) and those who appraised their brother or sister as having control over his or her own behavior ( β =-.18, p<.05) reported a lower-quality relationship than siblings who were less fearful and perceived their brother or sister as not having control over symptoms. Finally, siblings who perceived that they had experienced more personal gains from the challenges of coping with their brother's or sister's mental illness felt greater closeness and intimacy with him or her ( β =.37, p<.001).

|

Although the severity of psychiatric symptoms had no direct effect on relationship quality, siblings whose brother or sister had more severe symptoms reported greater fears (r=.34, p<.001) and fewer gains (r=-.22, p=.01) and perceived their brothers or sisters as having more control over their behavior (r=.30, p<.001). Using LISREL version 8.5, we conducted a post hoc analysis to determine whether severity of symptoms had a significant indirect effect on relationship quality. Using Sobel's ( 30 ) test for determining the significance of indirect effects, we found that psychiatric symptoms had a significant effect on relationship quality through their effect on control attributions (z=-1.97, p<.05) and the experience of personal gains (z=-2.38, p<.05). In other words, when the brother or sister was more symptomatic, siblings experienced fewer personal gains and were more likely to perceive their brother or sister as having control over symptoms, which, in turn, was related to having a poorer relationship. There was no significant indirect effect of symptoms on relationship quality through fears.

Discussion

The sibling relationship is the most enduring of all family relationships ( 31 ). Our findings suggest that closeness in the family during childhood sets the foundation for the quality of the sibling relationship in adulthood. There is an increasing effort to better diagnose and treat mental illness during childhood and adolescence. A major implication of our findings is the importance of early-intervention programs in acknowledging the needs of siblings. To the extent that early interventions focus on the whole family and help families maintain and strengthen bonds of affection, these interventions may have lifelong effects on sibling relationship quality.

As Solomon and colleagues ( 17 ) noted, few researchers have addressed the long-term impact on family relationships of physical violence or threats of such violence by individuals with mental illness. Although most individuals with schizophrenia never threaten or physically hurt another family member, our findings as well as those of others ( 18 ) suggest that a small but significant number of siblings have been victims of threats or acts of violence perpetrated by a brother or sister with schizophrenia ( 18 ). Even single incidents or threats of violence may have profound consequences for the future involvement of siblings ( 19 ). With the aging of the population and the death or disability of the parental generation, mental health providers may find themselves seeking a sibling when information is needed from a family member. Assessing whether siblings have been threatened or physically hurt by their sibling with mental illness is an important first step in determining how best to engage siblings as collaborators in the treatment process. By talking openly with siblings about past difficulties, providers may be able to help siblings put these previous behaviors in perspective. Also, clinicians can help siblings learn more effective strategies for responding to or managing these behaviors, and thus reduce their fears, which in turn should foster a closer sibling relationship.

Our findings also speak to the importance of working with siblings to explore their perceptions of their brother's or sister's illness. Siblings who expressed greater fear of their brother or sister and who perceived him or her as having control over symptoms reported having a less close relationship. Psychoeducation programs are typically designed to educate adults with mental illness and their families about the etiology and course of schizophrenia and to teach methods to manage difficult psychiatric symptoms or behaviors ( 32 ). When family members become more informed about mental illness, they may be less critical and more likely to appraise their relatives as having less control over their symptomatic behaviors ( 33 ). Also, by teaching family members more effective strategies to manage difficult behaviors and situations, these programs may help reduce the family members' fears about their relative ( 34 , 35 ). However, most participants in these programs are mothers, with few siblings attending this type of resource ( 36 ). Thus it is important for service providers to reach out and encourage siblings to participate in psychoeducation programs, which may require modification to meet their specific needs.

It is equally important to explore how siblings appraise the personal impact of their experience. Siblings who viewed themselves as having grown through the experience reported feeling closer to their brother or sister with schizophrenia than siblings who reported fewer gains from their experience. Encouraging siblings to join support groups provides opportunities to meet new friends and learn new skills, thus promoting personal growth. However, in the day-to-day stress of coping with mental illness, it may be difficult for siblings to reflect on how their lives have been transformed in positive directions as a result of coping with their sibling's illness. Thus it becomes important for mental health providers to work with siblings to help them recognize how their lives have been transformed positively in the process of coping with their brother's or sister's illness.

There are two important limitations to the study. First, all of the sibling respondents volunteered to participate in the research, which limits the generalizability of the study. In addition, we sampled siblings who were expected to be most involved in helping out their brother or sister with schizophrenia in the future. A different set of factors may affect the quality of the relationship among siblings who are less likely to be involved in the future. Additional research with a broader sample of siblings is needed to understand the range of factors influencing the quality of the sibling relationship.

Second, this is a cross-sectional study, and therefore, the causal ordering of the variables cannot be established. We recognize that the association between relationship quality and the predictor variables studied is highly complex and likely has bidirectional influences. For instance, although for theoretical reasons we examined how control attributions influenced relationship quality, relationship quality likely also affects the sibling's perception of how much control the brother or sister with schizophrenia has over his or her own symptoms. Longitudinal research is needed to examine this process over time.

Conclusions

With the aging of the population, research has begun to shift the focus from parents to siblings as future caregivers of their brothers and sisters with schizophrenia. Research indicates that the quality of the sibling relationship is a major contributor to sibling involvement in the future and to the quality of life of adults with schizophrenia ( 3 , 4 , 6 , 7 ). Our findings suggest that factors influencing the quality of sibling relationships depend on earlier life experiences as well as the siblings' current appraisal of their brother's or sister's behavior and their own perceptions of personal growth. By understanding and acknowledging these different dimensions of the sibling's experience, mental health providers will be better prepared to engage siblings in the treatment process and help promote stronger bonds of affection between adults with schizophrenia and their siblings.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Support for this study was provided to the Waisman Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison by grant R01-MH55928 (Dr. Greenberg, principal investigator) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and by NIMH training grant T32-MH17104 (Linda B. Cottler, Ph.D., principal investigator) through the Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Hatfield A, Lefley HP: Helping elderly caregivers plan for the future care of a relative with mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:103–107, 2000Google Scholar

2. Wasow M: The Skipping Stone: Ripple Effects of Mental Illness on the Family, 2nd ed. Palo Alto, Calif, Science and Behavioral Books, 2000Google Scholar

3. Smith MJ, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM: Siblings of adults with schizophrenia: expectations about future caregiving roles. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 77:29–37, 2007Google Scholar

4. Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Orsmond GI, et al: Siblings of adults with mental illness or mental retardation: current involvement and expectation of future caregiving. Psychiatric Services 50:1214–1219, 1999Google Scholar

5. Horwitz AV, Tessler RC, Fisher GA, et al: The role of adult siblings in providing social support to the severely mentally ill. Journal of Marriage and the Family 54:233–241, 1992Google Scholar

6. Smith MJ, Greenberg JS: The effects of the quality of sibling relationships on the life satisfaction of adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 58:1222–1224, 2007Google Scholar

7. Hatfield AB, Lefley HP: Future involvement of siblings in the lives of persons with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 41:327–338, 2005Google Scholar

8. Brody GH, Stoneman Z, McCoy J: Contributions of family relationships and child temperaments to longitudinal variations in sibling relationship quality and sibling relationship styles. Journal of Family Psychology 8:274–286, 1994Google Scholar

9. Pulakos J: Correlations between family environment and relationships of young adult siblings. Psychological Reports 67:1283–1286, 1990Google Scholar

10. Chodorow N: The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1978Google Scholar

11. Campbell L, Connidis I, Davies L: Sibling ties in later life: a social network analysis. Journal of Family Issues 20:114–148, 1999Google Scholar

12. Cicirelli VG: Feelings of attachment to siblings and well-being in later life. Psychology and Aging 4:211–216, 1989Google Scholar

13. Cicirelli VG: The longest bond: the sibling life cycle, in Handbook of Developmental Psychology and Psychopathology. Edited by L'Abate L. New York, Wiley, 1993Google Scholar

14. Gold DT: Sibling relationships: a typology. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 28:37–51, 1989Google Scholar

15. Connidis I: Life transitions and the adult sibling tie: a qualitative study. Journal of Marriage and the Family 54:972–982, 1992Google Scholar

16. Bedford V: Sibling relationship troubles and well-being in middle and old age. Family Relations 47:369–376, 1998Google Scholar

17. Solomon PL, Cavanaugh MM, Gelles RJ: Family violence among adults with severe mental illness: a neglected area of research. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 6:40–54, 2005Google Scholar

18. Estroff SE, Swanson JW, Lachicotte WS, et al: Risk reconsidered: targets of violence in the social networks of people with serious psychiatric disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:S95–S101, 1998Google Scholar

19. Lukens EP, Thorning H, Lohrer S: Sibling perspectives on severe mental illness: reflections of self and family. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 74:489–501, 2004Google Scholar

20. Greenley JR: Social control and expressed emotion. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 174:24–30, 1986Google Scholar

21. Robinson E: Causal attributions about mental illness: relationship to family functioning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:282–294, 1996Google Scholar

22. Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Judge K: Another side of the family's experience: learning and growing through the process of coping with mental illness. Journal of the California Alliance for the Mentally Ill 11:8–10, 2000Google Scholar

23. Bengtson VL, Schrader SS: Parent-child relationships, in Research Instruments in Social Gerontology. Edited by Mangen DJ, Peterson WA. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1982Google Scholar

24. Moos R, Moos B: Manual for the Family Environment Scale. Palo Alto, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1981Google Scholar

25. Greenley JR: Family symptom tolerance and rehospitalization experiences of psychiatric patients, in Research in Community Mental Health. Edited by Simmons R. Greenwich, Conn, JAI Press, 1979Google Scholar

26. Greenberg JS, Kim HW, Greenley JR: Factors associated with subjective burden in siblings of adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:231–241, 1997Google Scholar

27. Pearlin LI: Caregiver's Stress and Coping Study. Grant NIMH R01-MH42122. San Francisco, University of California, Human Development and Aging Programs, 1988Google Scholar

28. Greenley JR, McKee D, Stein LI, et al: Labeling mental illness in families. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, San Francisco, May 6–12, 1989Google Scholar

29. Cuffel B, Fischer E, Owen R, et al: An instrument for measurement of outcomes of care for schizophrenia: issues in development and implementation. Evaluation and the Health Professions 20:96–108, 1997Google Scholar

30. Sobel ME: Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models, in Sociological Methodology. Edited by Leinhardt S. Washington, DC, American Sociological Association, 1982Google Scholar

31. Cicirelli VG: Sibling Relationships Across the Lifespan. New York, Plenum, 1995Google Scholar

32. McFarlane WR, Dixon L, Lukens E, et al: Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 29:223–245, 2003Google Scholar

33. Barrowclough C, Hooley JM: Attributions and expressed emotion: a review. Clinical Psychology Review 23:849–880, 2003Google Scholar

34. Biegel DE, Yamatani H: Self-help groups for families of the mentally ill: research perspectives, in Family Involvement in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Edited by Goldstein MZ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1986Google Scholar

35. Heller T, Roccoforte JA, Hsieh K, et al: Benefits of support groups for families of adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:187–198, 1997Google Scholar

36. Pollio DE, North CS, Osborne V, et al: The impact of psychiatric diagnosis and family system relationship on problems identified by families coping with a mentally ill member. Family Process 40:199–209, 2001Google Scholar