A Theory of Social Integration as Quality of Life

In the 1980s, the presence of persons with severe mental illness on the streets and in homeless shelters occasioned a crisis requiring a response ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). Later, the movement for mental health system reform brought another shift in priorities. With managed care came demands for cost-effectiveness ( 14 ), measurable outcomes ( 15 ), and evidence-based standards for the treatment of severe mental illness ( 16 , 17 ). The emphasis on quality of life has been largely eclipsed as a result.

This article returns attention to this topic, raising questions about what quality of life in the context of severe mental illness should mean as both an outcome of treatment and an object of research. We aim to reformulate the concept in a way that sets higher standards, reflects the new emphasis on recovery, and construes quality of life not only as well-being but also as agency ( 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ). Social integration serves as our substantive focus. We define social integration as a process through which individuals with psychiatric disabilities develop and increasingly exercise capacities for interpersonal connectedness and citizenship ( 24 ).

A capabilities approach to quality of life

The capabilities approach to human development provides the conceptual framework for this exercise. The product of decades of scholarship in development economics and moral philosophy ( 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ), the capabilities approach reconceptualizes quality of life for disadvantaged populations ( 30 ). It was developed as an alternative to utilitarian formulations that use personal satisfaction and income as primary quality-of-life indicators. Until recently, the capabilities approach has been associated principally with the study of standards of living for poor people in developing countries. We are now seeing it put to other uses, including rethinking disability and disparities in health ( 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ). All of these efforts target social structures outside service systems.

Our goal here, in contrast, is to use this set of ideas to construct an individual-level theory that can guide efforts to foster social integration for persons with psychiatric disabilities receiving mental health care. From a capabilities perspective, quality of life is construed in terms of agency, that is, intentional, self-directed action. Realization of agency is dependent upon the synergistic combination of two essential ingredients: personal capacity and social opportunity.

Personal capacity refers to attributes of individuals that equip them to exercise agency. Capacities are both inherent and developed, meaning that a certain amount of capacity may "come naturally." Inherent capacities improve and new ones are acquired with learning and practice. Personal capacities constitute "agency potential."

Capacities are not the same as skills. Though both suggest competence, we may think of skills as competencies acquired through practice, such as playing the piano or—in the context of mental health treatment—symptom management, emotion regulation, or stress reduction ( 36 , 37 , 38 ). Capacities, in contrast, are competencies acquired through developmental processes aimed at moral, social, cognitive, and emotional growth. Skills may be thought of as performative and capacities as generative.

Opportunities are real options for action in the social world outside service systems. To take advantage of opportunities, individuals must have both the requisite personal capacities and the needed resources. Reading, for example, requires both literacy (capacity) and reading material (resource). The ability to take advantage of opportunities is mediated by circumstances of the social environment—social processes (for example, discrimination), laws, customs, and policies. Real opportunities enable an individual to pursue socially valued ends. Both the pursuit and the achievement of these ends improve quality of life. In what follows, we use the term "occasion" to refer to opportunities occurring as part of mental health care.

The research

This article is the second in a planned series of reports from an anthropologically informed, qualitative study. The study used the capabilities approach to define social integration in the context of psychiatric disability and build a theory that explains how capacity development for social integration may take place. Data were collected from 2003 to 2005. The first report from the study offered a new definition of social integration (see above) ( 24 ). Here, we address the study's second, theory-building objective.

Methods

Data collection

Two types of data collection activities were carried out for this study: individual in-depth interviews and brief ethnographic visits. In-depth interviews were conducted with adults who had been psychiatrically disabled but who, in the judgment of the investigators, had become more socially integrated since disablement. Judgments were based upon information forwarded by service providers and made collectively by the research team. Interviews were unstructured and worked to elicit detailed accounts of experiences related to social integration. Seventy-eight interviews were conducted with 56 interviewees.

Brief ethnographic visits were short stays at service sites that work to foster social integration for persons with psychiatric disabilities. The purpose of the visits was to understand how this takes place. Eight visits were made to five programs: a psychiatric rehabilitation facility, a consumer-run drop-in center, a therapeutic community, a residential and employment program aimed at "redefining community," and a community-based treatment center for young adults with psychosis. Visits lasted for one to two days and included interviews with staff and program users and field observations.

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Studies at the Harvard Medical School and by the Institutional Review Board at the Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants with an approved consent form.

Data analysis

Strategies for analyzing qualitative data are not simply pulled "off the shelf" but rather custom built to fit each investigation ( 39 , 40 ). To construct a theory showing how capacities for social integration may develop for individuals with psychiatric disabilities, we used a theory-driven-but-inductive approach to data analysis informed by the capabilities approach. The observational and interview data were analyzed—first, to specify the capacity construct and second, to characterize occasions for capacity building in mental health care.

We posed two analytical questions: What capacities are needed for connectedness and citizenship? and What do occasions for building capacities that foster connectedness and citizenship look like? To address these questions, interview transcripts and materials derived from observations (notes on ethnographic visits, notes on investigator discussions of ethnographic visits, and transcripts and recordings of interviews conducted during visits) were reviewed and discussed in face-to-face, day-long meetings of the research team and in telephone conferences. Twenty-three such meetings and conferences took place over two-and-a-half years.

To identify capacities needed for social integration, the team selected from the larger corpus of data sections of text that they judged to represent instances of connectedness and citizenship. We then characterized the capacities involved by naming and defining them in ways intended to reflect both the meanings inherent in the text (in contrast, for example, to dictionary definitions) and insights and understandings developed in the course of conducting the research. This analytic strategy is informed by the grounded theory approach to qualitative data analysis ( 41 , 42 , 43 ).

Much the same procedure was used to characterize occasions for capacity building. Sections of text that represented interpersonal interactions between individual providers and recipients of mental health care and that were judged to exemplify an occasion were identified, named, contextualized, and interpreted by the team. Names were selected to represent the change processes that defined each interaction as an occasion. This means that occasions are represented as mechanisms of change.

Once instances of capacities and occasions had been fleshed out, a hypothetical process specifying how they interact, informed by the capabilities approach, was formulated. The statement of this process is the promised working theory of capacity building for social integration.

Results

Presentation of study results reflects the theoretically informed, yet inductive analytical process described above. We show how the analytical questions intended to specify capacities and occasions were answered, and we lay out the theory of capacity development for social integration.

To answer the analytical questions, six capacities and five types of occasions were identified. Capacities are moral, social, cognitive, and emotional competencies that build maturity and anchor social action. Occasions are represented as change mechanisms fostering capacity development. An overview appears in Figure 1 .

What capacities are needed for connectedness and citizenship?

The following capacities are suggested by the data.

• Responsibility is the ability to act in ways that reflect consideration and respect for others.

• Accountability is being answerable to others for the consequences of one's actions in the context of a given set of social or moral standards.

• Imagination is the ability to form ideas and images in the mind and know they are mental creations.

• Empathy is the ability to envision, understand, or identify with others' points of view.

• Judgment is the ability to form sound opinions and sensible decisions in the absence of complete information.

• Advocacy is the ability to argue articulately for a position orally or in writing.

The relative salience of social, emotional, cognitive, and moral dimensions varies across capacities. Empathy, for example, is prominently social and emotional. Cognitive and emotional dimensions are especially salient in advocacy. In responsibility and accountability, social and moral dimensions come most quickly to the fore. A major advantage of the capacity construct and the larger capabilities approach is that they highlight the moral dimension of agency, thus allowing moral experience, or "what really matters" ( 44 ), to be introduced into the discourses on social integration following psychiatric disability and the meaning of recovery from mental illness.

What do occasions for building capacities look like?

To address this question, five types of occasions were identified. Occasions are defined as structured mechanisms of change leading to capacity development. Here, mechanisms of change are embedded in microexchanges between mental health providers and users of care. In each type of occasion, change is directed at building capacity for connectedness or citizenship. The five types of occasions represented—contradiction, reinterpretation, rehearsal, raising expectations, and confrontation—are those most salient in the study data.

Contradiction. Mr. M, who was an interviewee, described being evicted from a homeless shelter because of repeated rule infractions. He was angry about the eviction. However, his anger was tempered—and complicated—by the fact that although shelter staff had instigated the move, they had also found him a new placement, helped him pack his things, and driven him to his new residence. Mr. M was impressed but also confused: "I couldn't just call them jerks!" he exclaimed. "True, they kicked me out, but look what they also did for me!" This seemingly contradictory juxtaposition of callousness and concern triggered a shift in both perspective and behavior for M. "I remember it really clearly," he said. "I got to the new place, and when I walked through the door I said to myself, 'This is my chance to do things differently.' And I did. It started there. I started being accountable to people."

Reinterpretation. Reinterpretation is occasioned by encounters with new meanings of a familiar idea. In the following interview excerpt, Ms. S recounts an experience of being asked to "call in" to the halfway house where she was staying. In the course of the interaction, she encounters a new meaning of "call in." Though calling in had been previously experienced as an infringement on her independence, in the interaction depicted below Ms. S was presented with the fact that calling in can also signify consideration for others. Learning and acting on this new meaning, Ms. S subsequently became more "responsible."

"I remember the first time they asked me to call in when I went somewhere. It was like, 'Call in? You ain't my mother! I ain't callin' you. It's my business where I go and what I do!' And she [staff person] was like, 'But we worry about you!' And I said, 'Nobody worries about me, so don't even go there. I'm just here for a place to live until I can get through school and get my own apartment.' And she was like, 'Well if that's all you're doing here, you could go back and sit on a ward and do that.' And I was like, 'Wait a minute, what do you mean?'"

Rehearsal. Enactment is essential to capacity. Hence a third capacity-building mechanism is rehearsal. By rehearsal, we mean executing a developing capacity in a learning environment, with the expectation of feedback. The psychiatric rehabilitation program participating in this study enables participants to rehearse being students by using an adult education model of practice. The community-based psychosis treatment center organizes theater workshops led by professional actors who stage rehearsals of emotional and imaginative capacities—empathy in the form of adopting multiple perspectives on a situation, for example. By creating a "living-learning" environment for the practice of reciprocal relationships, the therapeutic community we visited functions continuously as a "rehearsal stage" for connectedness and citizenship in the larger social world (Dickey B, Ware NC, unpublished manuscript). Rehearsal may usefully be contrasted with practice, cited above as a means of skill development. As a capacity-building mechanism, rehearsing creates experience.

Raising expectations. In a fourth example, we see increased sociability brought about through a subtle raising of expectations. During a study interview, Mr. R referred to a "turning point" after which he became more open to connecting with others. As Mr. R described it, conditions for the change were created by Ms. T, a mental health practitioner who was consistently respectful and "nice" to Mr. R. When he returned her greetings with "go to hell," she simply smiled. When he hung up on her telephone calls, she proceeded as if nothing had happened, inquiring after his well-being as usual. Then, one day, Ms. T's congeniality cooled. "She stopped talking to me," Mr. R reported. "She stopped saying 'hi,' asking me how I was doing." Mr. R found he missed the "attention." The pull of the connection he had come to expect outweighed the urge to remain interpersonally distant. Tentatively, he "tested the waters," as he put it—initiating greetings, being the first to "say hi." "And that's how it started," Mr. R concluded. "Little by little. Talking. Then the conversations started getting longer and longer. Next thing you know, I was in her therapy groups."

By exhibiting warmth and respect, Ms. T modeled an alternative to Mr. R's characteristic rudeness and expressions of anger. By pulling back at a certain point, she signaled that his usual demeanor was no longer acceptable, in effect "changing the rules" of interaction between them and setting a higher standard. The new standard required that respect be warranted or "earned" through socially acceptable behavior. Mr. R promptly responded, becoming more considerate and respectful—"nicer"—and more connected to others.

Confrontation. The last mechanism we term "confrontation." By confrontation we mean deliberate challenges to actions that fail to meet accepted standards. Confronting unacceptable actions on the part of individuals with severe mental illness sets an expectation of accountability. It assumes capacity, reinforces connectedness, and communicates that how one acts affects others—that in social interactions, something real is at stake. This is aptly illustrated in the following interview excerpt, in which a staff person at the participating therapeutic community describes her response to a resident who "faked" an injury to escape work responsibilities.

"My first thought was I want him punished. But because I felt that way I realized the worst thing I could do was talk to him at the time. So I wrote him a note about how it felt to be lied to, and how it felt to realize that he was a dishonest person, and that our trust was broken, and that that was going to have lasting consequences. The consequences that arise from people's actions are natural, and as a natural consequence of his lying to people, I'm not gonna trust him. And that's going to be really hard for us to work around."

Not every capacity-building occasion produces immediate change, as the remainder of this anecdote makes clear. The staff person's attempt to communicate a lesson in the interpersonal consequences of dishonesty initially went unheeded—her note was interpreted and dismissed as simply a "list of complaints." Subsequent attempts, at least one of which involved third-party mediation, led to an understanding of the grievance (note: a form of empathy) on the part of the resident. Eventually, the relationship was, if not strengthened, at least returned to its original state.

A theory of capacity building for social integration

Having laid out the building blocks of the theory—capacity, occasion, mechanism—we come now to the task of assembling them into a proposition, as follows:

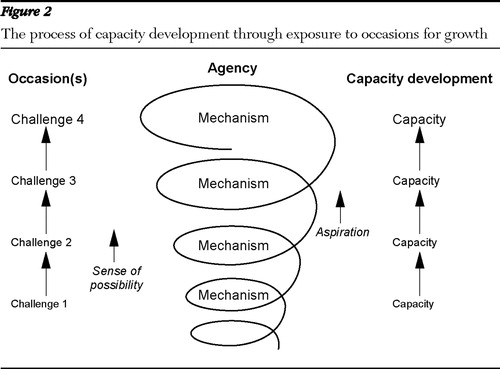

• Individuals with psychiatric disabilities bring preexisting capacities to the development process. Existing capacities expand, and new ones take root, through exposure to occasions for growth. Occasions present challenges and may be simple or complex, that is, made up either of single interactions or of orchestrated sequences arranged in order of increasing difficulty. As challenges are mastered via mechanisms—contradiction, reinterpretation, confrontation—competency is affirmed. A sense of possibility emerges, and with it, aspiration. Together, aspiration and a sense of possibility fuel engagement with new, more challenging occasions. Capacity builds and expands into agency in an iterative, open-ended process.

This process is depicted schematically in Figure 2 .

Occasions for capacity development share a number of characteristics. They assume that capacity development is possible and will take place. Practitioners act accordingly by setting expectations for performance and insisting that the expectations be met. They also allow for the possibility of failure and, when it occurs, find constructive ways of responding. Constructive responses examine failure and place it in perspective but also allow the consequences to unfold. Genuine actions and events are characterized by the fact that something significant is at stake.

The development process is expected to be neither uniform across capacities nor steady in pace. Slippage, stalling, and temporary reversals will occur. Unexpected obstacles will crop up. Challenges will be declined. An adequate theory must account for such contingencies, as the representation we offer attempts to do.

Discussion

Our intent has been to construct a working theory of capacity development for social integration that applies to persons who have been psychiatrically disabled. The theory reflects the capabilities approach. The capabilities approach offers several advantages as a conceptual framework. It assumes diversity and treats growth rather than chronicity as a way of thinking about life possibilities following psychiatric disability. Growth is the contingent outcome of a dialectic between the individual and the social context. The development process is thus one in which occasions for growth follow and build upon one another in order of increasing difficulty. Success and failure, trial and error, are expected parts of the process. Finally, the capabilities approach leads to a framing of quality of life following psychiatric disability that prioritizes capacity for reflective action over satisfaction and functioning.

The working theory posits a spiral-like growth process through which once-disabled persons increase social integration through capacity development. We envision the theory as applicable not only to social integration but also to other aspects of quality of life. We expect it to prove useful in thinking about social integration for persons with nonpsychiatric disabilities and other forms of disadvantage. We hope it will serve as a useful starting point for future empirical research and practice.

Social integration following psychiatric disability may be an ideal goal, but substantial progress in that direction is not out of reach. Field research for this project revealed a number of systematic and innovative approaches to addressing connectedness and citizenship as goals of care. Supported employment programs have placed individuals with psychiatric disabilities in competitive jobs with demonstrated success ( 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ). In Europe, intensified campaigns for "social inclusion" have reduced barriers to full social participation for persons with psychiatric disabilities—by affirming rights, addressing public fears, correcting misinformation, and overcoming workplace obstacles ( 50 , 51 ).

Evidence accumulating as part of the "renaissance" in social psychiatry research ( 52 ) points to environmental factors as antecedents of psychosis. Migration, discrimination, urban upbringing, and early childhood trauma have all recently been implicated as risk factors for psychotic disorders in epidemiological research ( 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ). The positing of causal mechanisms capable of explaining statistical associations adds depth to this area of inquiry and promises further progress in understanding psychosis ( 61 , 62 ).

The working theory outlined here resonates with the social psychiatry "renaissance." However, it shifts the emphasis from origins to consequences of illness. The fundamental question we address is this: What kind of life should individuals who have been psychiatrically disabled reasonably be entitled to expect? Social integration in the form of interpersonal connectedness and active citizenship should be a reasonable expectation, we argue, but as a means to a larger end. The ultimate advantage of using the capabilities approach to rethink the consequences of disability is that it leads us to define quality of life in terms of agency rather than well-being alone. From a capabilities perspective, social integration improves quality of life by equipping people for deliberate action and reflective choice.

Conclusions

Several questions remain to be answered as this initiative moves forward. What other capacities contribute to social integration besides those we have discussed? How should "occasions" be further specified? How can occasions be linked to opportunities outside the domain of mental health care? And finally, how can the concepts and processes outlined here be operationalized and measured to allow us to both test the theory and begin to put it into practice? Implementation of these ideas is an important next step.

The data presented here demonstrate that capacities for social integration can be effectively developed as part of everyday routines of mental health care. Providers tell us that they find the theory useful as an analytical framework for critiquing their own work. In the future, we expect it to inform the design of interventions aimed at increasing agency as part of recovery from severe mental illness—for example, shared decision making in medication management ( 63 ). At some point, the process of assisting individuals in agency development will require coordination of mental health and other service sectors. However, the process must ultimately involve a shift from development to exercise of capacities if recovery is to mean participation as full citizens in the social world outside mental health care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by a grant R01-MH-065247 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The contributions of study participants—practitioners as well as service users—are gratefully acknowledged by the authors, who also thank Madeleine Smith, M.S.W., for assistance in conducting the research.

The authors report no competing interests

1. Schulberg HC, Bromet E: Strategies for evaluating the outcome of community services for the chronically mentally ill. American Journal of Psychiatry 55:302–308, 1981Google Scholar

2. Tessler RC, Goldman HH: The Chronically Mentally Ill: Assessing Community Support Programs. Cambridge, Mass, Bullinger, 1982Google Scholar

3. Bigelow DA, Brodsky G, Steward L, et al: The concept and measurement of quality of life as a dependent variable in evaluation of mental health services, in Innovative Approaches to Mental Health Evaluation. Edited by Stahler GJ, Tash WR. New York, Academic Press, 1982Google Scholar

4. Baker F, Intagliata J: Quality of life in the evaluation of community support systems. Evaluation and Program Planning 5:69–79, 1982Google Scholar

5. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51–62, 1988Google Scholar

6. Lewis DA, Riger S, Rosenberg H, et al: Worlds of the Mentally Ill: How Deinstitutionalization Works in the City. Carbondale, Ill, Southern Illinois University Press, 1991Google Scholar

7. Estroff SE: Making It Crazy. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1981Google Scholar

8. Hopper K: Returning to the community—again. Psychiatric Services 53:1355, 2002Google Scholar

9. Lamb HR: The Homeless Mentally Ill: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1984Google Scholar

10. Lamb HR, Bachrach LL, Kass FI: Treating the Homeless Mentally Ill: A Report of the Task Force of the American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1992Google Scholar

11. Leshner AO: Outcasts on Main Street: Report of the Federal Task Force on Homelessness and Severe Mental Illness. Washington, DC, Interagency Council on the Homeless, 1992Google Scholar

12. Jones JM, Levine IS, Rosenberg AA: Homelessness research, services and social policy: introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist 46:1109–1111, 1991Google Scholar

13. Cohen NL: What we must learn from the homeless mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:101, 1992Google Scholar

14. Essock SM, Goldman HH: States' embrace of managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):34–45, 1995Google Scholar

15. Sederer LI, Dickey B: Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1995Google Scholar

16. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM, the Co-Investigators of the PORT Project: At issue: translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–10, 1998Google Scholar

17. Drake RE, Merrens MR, Lynde DW: Evidence-Based Mental Health Practice. New York, Norton, 2005Google Scholar

18. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

19. Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990's. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:11–23, 1993Google Scholar

20. Davidson L: Living Outside Mental Illness: Qualitative Studies of Recovery in Schizophrenia. New York, New York University Press, 2003Google Scholar

21. Jacobson N, Greenley D: What is recovery? A conceptual model and explication. Psychiatric Services 52:482–485, 2001Google Scholar

22. Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, et al: Illness management and recovery: a review of the research. Psychiatric Services 53:1272–1284, 2002Google Scholar

23. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A: Recovery from schizophrenia: a concept in search of research. Psychiatric Services 56:735–742, 2005Google Scholar

24. Ware NC, Hopper K, Tugenberg T, et al: Connectedness and citizenship: redefining social integration. Psychiatric Services 58:469–474, 2007Google Scholar

25. Sen AK: Equality of what?, in The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Edited by McMurrin S. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1980Google Scholar

26. Sen A: Commodities and Capabilities. Oxford, United Kingdom, North-Holland, 1985Google Scholar

27. Sen AK: Inequality Re-examined. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1992Google Scholar

28. Sen AK: Development as Freedom. New York, Knopf, 1999Google Scholar

29. Nussbaum MC: Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge, United Kingdom, Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 2000Google Scholar

30. Nussbaum M, Sen A: The Quality of Life. Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 1993Google Scholar

31. Olson K: Distributive justice and the politics of difference. Critical Horizons 2:5–32, 2001Google Scholar

32. Burchardt T: Capabilities and disability: the capabilities framework and the social model of disability. Disability and Society 19:735–751, 2004Google Scholar

33. Ruger JP: Health and social justice. Lancet 364:1075–1080, 2004Google Scholar

34. Nussbaum M: Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 2006Google Scholar

35. Hopper K: Rethinking social recovery in schizophrenia: a capabilities approach. Social Science and Medicine 65:868–879, 2007Google Scholar

36. Liberman RP, DeRisi WU, Mueser K: Social Skills Training for Psychiatric Patients. New York, Pergamon, 1989Google Scholar

37. Copeland ME: Wellness Recovery Action Plan. West Dummerston, Vt, Peach Press, 1997Google Scholar

38. Linehan M: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

39. Creswell JW: Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1998Google Scholar

40. Miles MB, Huberman AM: Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1994Google Scholar

41. Glaser BG, Strauss AL: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York, Aldine, 1967Google Scholar

42. Strauss A: Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 1987Google Scholar

43. Strauss A, Corbin J: Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1990Google Scholar

44. Kleinman A: What Really Matters: Living a Moral Life Amidst Uncertainty and Danger. New York, Oxford University Press, 2006Google Scholar

45. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391–399, 1996Google Scholar

46. Becker DR, Drake RE: A Working Life for People With Severe Mental Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

47. Salyers MP, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: A ten-year follow-up of a supported employment program. Psychiatric Services 55:302–308, 2004Google Scholar

48. Mueser KT, Clark RE, Haines M, et al: The Hartford study of supported employment for persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 72:479–490, 2004Google Scholar

49. Latimer EA, Lecomte T, Becker DR, et al: Generalisability of the individual placement and support model of supported employment: results of a Canadian randomised-controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 189:65–73, 2006Google Scholar

50. Sayce L: Social inclusion and mental health. Psychiatric Bulletin 25:121–123, 2001Google Scholar

51. Leff J, Warner R: Social Inclusion of People With Mental Illness. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2006Google Scholar

52. McGrath JJ: The surprisingly rich contours of schizophrenia epidemiology. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:14–16,2007Google Scholar

53. King M, Coker E, Leavey G, et al: Incidence of psychotic illness in London: comparison of ethnic groups. British Medical Journal 309:1115–1119, 1994Google Scholar

54. Van Os J, Castle DJ, Takei N, et al: Psychotic illness in ethnic minorities: clarification from the 1991 census. Psychological Medicine 26:203–208, 1996Google Scholar

55. Zolkowska K, Cantor-Grace E, McNeil TF: Increased rates of psychosis amongst immigrants to Sweden: is migration a risk factor for psychosis? Psychological Medicine 31:669–678, 2001Google Scholar

56. Fearon P, Kirkbride J, Morgan C, et al: Patterns of psychosis in black and white minority groups in urban UK: the AESOP study. Schizophrenia Bulletin 31:222, 2005Google Scholar

57. Bebbington PE, Bhugra D, Brugha T, et al: Psychosis, victimization and childhood disadvantage: evidence from the second British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. British Journal of Psychiatry 185:220–226, 2004Google Scholar

58. Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Bak M, et al: Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109:38–45, 2004Google Scholar

59. Marcelis M, Navarro-Mateu F, Murray R, et al: Urbanization and psychosis: a study of 1942–1978 birth cohorts in The Netherlands. Psychological Medicine 28:871–879, 1998Google Scholar

60. Pedersen CB, Mortensen PB: Evidence of a dose-response relationship between urbanicity during upbringing and schizophrenia risk. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:1039–1046, 2001Google Scholar

61. Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E: Social defeat: risk factor for schizophrenia? British Journal of Psychiatry 187:101–102, 2005Google Scholar

62. Morgan C, Fisher H: Environment and schizophrenia: environmental factors in schizophrenia: childhood trauma—a critical review. Schizophrenia Bulletin 33:3–10, 2007Google Scholar

63. Deegan PE, Drake RE: Shared decision making and medication management in the recovery process. Psychiatric Services 57:1636–1639, 2006Google Scholar