Relationships Among Subjective and Objective Measures of Adherence to Oral Antipsychotic Medications

Adherence to medication plays an important role in maximizing outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). Unfortunately, up to 60% of outpatients with schizophrenia do not take medications as prescribed ( 1 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ). A majority of patients discontinue antipsychotic medications for multiple reasons ( 9 ). Poor adherence to oral antipsychotic medication leads to rehospitalization, derails the process of recovery, and contributes to the high cost of treating schizophrenia ( 1 , 10 , 11 ). Second-generation antipsychotics with arguably broader efficacy and more favorable side effect profiles have not substantially improved rates of adherence for individuals with psychosis ( 1 , 12 , 13 , 14 ).

Medication prescribing guidelines recommend effective dose ranges, adequate medication trial length, and careful monitoring of symptoms to improve outcomes ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ). Guidelines base decisions for all but the most obviously nonadherent patients on the assumption that medication is being taken as prescribed. It remains unclear how prescribing physicians determine whether patients are adhering to medication. Unidentified problem adherence can lead to unnecessary increases in medication dosage, prescription of adjunctive medications, changes among medications, and the mistaken identification of patients as "treatment resistant" ( 1 , 19 ). If physicians assume that nonadherence is the reason for poor response among clinically unstable patients who are taking medication as prescribed, the physicians may continue to prescribe the same medications when more efficacious alternatives may be available.

The most common ways of assessing adherence to oral antipsychotic medications in both research and in clinical practice are self-report and physician or treatment provider report ( 20 ). In a review of 124 studies covering more than three decades, we found that self-report and physician report were used to assess adherence 159 times ( 20 ). Self-report overestimates adherence ( 1 , 20 ). In the absence of more objective data, physician report may be based on appointment adherence, the clinical state of the patient, and the patient's report.

Byerly and colleagues ( 21 ) conducted one of the only studies investigating agreement between electronic monitoring (pill bottle caps that record the time and date of opening) and clinician ratings on a scale describing patients' participation in treatment (N=30). Nonadherence was identified among 48% of participants by electronic monitoring; none of the clinicians detected nonadherence. Asking physicians to estimate percentage of medication intake may lead to stronger correlations between electronic monitoring and physician ratings. However, in a recently published follow-up study, Byerly and colleagues ( 22 ) compared patient self-report, researcher ratings, and electronic monitoring of adherence behavior to ratings of adherence based upon physicians' impressions of the percentage of medication taken by the patient. Results suggested far greater rates of nonadherence with electronic monitoring than either self-report or physician ratings.

The study presented here examined relationships among multiple measures of adherence and relationships between adherence and clinical state among outpatients with schizophrenia taking oral antipsychotic medications.

Methods

Design

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. All individuals gave written informed consent before participation. Fifty-two patients with schizophrenia were recruited. Twenty-six were recruited from the Tri-County Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation (MHMR) Service (Conroe, Texas), and 26 were recruited from the El Paso community MHMR Center. No differences between sites were found with respect to demographic and baseline variables. Note that this was not a systematically collected sample but a sample of convenience. Mental health staff approached patients they believed would participate. This may have biased the sample toward more adherent patients.

Demographic information and symptom ratings were obtained during a baseline visit. Medication adherence was assessed by various methods (see below) for the next 12 weeks from the index visit to the end of the study.

Participants

Participants were recruited from April 2004 to March 2005 at a routine clinic visit. In addition to being diagnosed by the treating physician as having schizophrenia according to DSM-IV criteria, participants had to be between the ages of 18 and 55 years; have no documented history of head injury, mental retardation, or neurologic disorder; and be given a prescription for olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol (medications for which blood level assays were available to our laboratory at the start of the study).

Demographic characteristics

Fifty-three individuals agreed to participate, but one was dropped because of not meeting full inclusion criteria, leaving a total of 52 participants. The mean±SD age of participants was 42.4±9.78 years. Twenty-seven (52%) were male, and 25 (48%) were female. Twenty-two (42%) were non-Hispanic white, 21 (40%) were Latino, and nine (17%) were African American. Positive symptoms as rated from the expanded version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) ( 23 ) were in the mild to moderate range (mean score of 2.97±.84; possible scores range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater levels of symptomatology). Thirty patients (58%) were on risperidone, 20 (38%) were on olanzapine, and two (4%) were on haloperidol. Mean daily dosages were 3.95±2.44 mg per day, 17.75±10.35 mg per day, and 11.67±7.64 mg per day, respectively. Forty-nine patients (94%) were also on concomitant medications.

Assessments

Medication adherence. Medication adherence was assessed with participant self-report, provider report, pill counts, electronic monitoring, and blood plasma levels of antipsychotics. Participants taking 80% or more of their prescribed dose were classified as adherent.

For self-report, at their 12-week follow-up clinic visit participants were asked to mark on a visual analog scale from 0% to 100% the amount of medication that they believed they had taken since their baseline visit. Although it is not ideal to ask patients with schizophrenia to describe pill-taking behavior over such a long period of time, this procedure most closely matches psychiatric visits in which physicians inquire about medication taken since the last time the patient was seen.

Provider report was rated at follow-up on the same scale from 0% to 100%. Physicians were asked to give their impression of the amount of medication taken by the patient since the last clinic visit.

Every two weeks on unannounced home visits, pills were counted and data were retrieved from electronic medication caps. This procedure was designed to eliminate the demand on the patient to bring in pill containers or caps, a method that biases results by obtaining more complete data on compliant patients. Participants were asked to contact the researcher when a refill of medication was obtained.

The number of pills available at each home visit was used to calculate adherence for the preceding two-week period. Prescribing information provided on the label indicated the number of tablets prescribed. A mean pill count percentage was computed ([number of pills missing from the bottle and presumed taken during each two-week period ÷ the number of pills prescribed] × 100). Nonadherent doses were counted for days in which the prescription had run out and no refill had yet been obtained. In cases in which more than one bottle of pills was present on a visit (refill obtained), both bottles were counted and the total number of pills missing (assumed to be taken) was computed.

Data from electronic caps was downloaded onto a computer after counting pills. Openings for counting or adding medications were deleted. As with pill count, electronic monitoring adherence was the number of adherent doses—that is, number of openings (number of doses assumed taken) ÷ total number of doses prescribed for each two-week period averaged across the 12-week follow-up. Timing of dose was not used to determine adherence because prescriptions were sometimes written without specifying times for dosage—for example, one tablet each morning.

During the first and last two weeks of the study, blood was sampled on two randomly selected occasions approximately 72 hours apart. Draws were conducted before breakfast and before the morning dose of medication would have been taken. These data were used to explore the utility of blood plasma concentrations to assess adherence among partially adherent patients. Novel ways to utilize blood plasma concentration are necessary in that interindividual variability is high. Moreover, the dose-response relationship for second-generation antipsychotics is unclear and can be affected by a number of variables, including concomitant medications, genetic metabolic factors, and smoking ( 24 , 25 ). Using the individual as his or her own baseline for examining variability over time in plasma concentration addresses some of these issues.

The two blood samples taken over the last two weeks of the study were evaluated for consistency of antipsychotic plasma levels by using the coefficient of variability ( 26 ). If a participant had more than 30% variability in these two trough levels of his or her antipsychotic, the patient was considered to be nonadherent. In a previous study of patients who were found to be adherent to antipsychotic medication on the basis of electronic monitoring, we found 98% to have a coefficient of variability for sequential plasma concentrations of 30% (mean coefficient of variability=14.23%±6.47%) ( 27 ).

Differences in concentration-to-dose ratio between the means of the initial two draws and the two follow-up draws were examined to identify consistency in antipsychotic plasma levels over the course of the study. This was done in a probative fashion to determine whether such a measure would correlate with other measures of adherence that were examined across the course of the study, such as pill count and electronic monitoring. If the mean concentration-to-dose ratio differed by more than 30% across the 12 weeks, patients were considered to be nonadherent. Thus concentration-to-dose ratio across 12 weeks was examined as only a dichotomous variable. The cutoff of 30% variability within participants was based on preliminary data from our laboratory suggesting that trough levels varied across time less than 30% when medication was at steady state and administration of medication was supervised. Note that this is an appropriately more stringent criterion to identify nonadherence within participants than that suggested by de Leon ( 24 ) to identify clinically relevant deviation between participants.

Symptomatology. Symptomatology was assessed by trained case managers at regular clinic visits at baseline and study termination using the expanded version of the BPRS ( 23 ) and the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI) ( 28 ). The positive symptom factor of the BPRS (mean of items assessing conceptual disorganization, delusions, hallucinations, and suspiciousness) was utilized as a measure of positive symptoms ( 29 ). Possible scores for the CGI and positive symptom factor score range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating more severe symptomatology. For each measure, we also calculated a difference score across the 12-week period reflecting change in clinical state.

Data analysis

Because adherence data were not normally distributed and included paired observations, relationships between measures of adherence and between measures of adherence and clinical state were examined by using Kendall tau correlation coefficients. To examine the relationship between dichotomous data on antipsychotic plasma levels and clinical state we used a point-biserial correlation. Data are presented both uncorrected and corrected for multiple comparisons. In addition, dichotomous variables were examined by using the kappa statistic to examine agreement between two methods, controlling for chance agreement. A priori we defined electronic monitoring scores as the best standard against which to judge other methods. Although imperfect, electronic monitoring has been viewed as a reference standard against which other methods can be judged ( 30 ).

Results

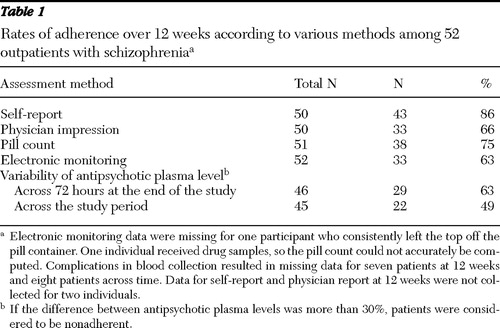

The percentage of adherent patients identified by each method is presented in Table 1 . Rates of adherence were highest when assessed with self-report. Rates of adherence assessed by physicians were similar to those assessed with electronic monitoring. Antipsychotic plasma levels suggest that patients were consistently taking their medication over brief periods (72 hours). However, concentration-to-dose ratios were not consistent over the course of 12 weeks and identified a lower percentage of adherent participants than any other method.

|

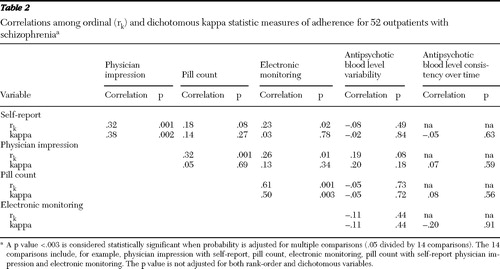

Correlations between adherence measures appear in Table 2 . Pill count and electronic monitoring were weakly correlated with subjective measures when scores were examined as ordinal variables. Electronic monitoring and pill count were most strongly correlated among adherence measures whether data were ordinal or dichotomous. Antipsychotic plasma levels were not significantly correlated with any other measure of adherence. When the analysis corrected for multiple comparisons, only the correlations between pill count and electronic monitoring and between pill count and physician impression were statistically significant. When the sample was dichotomized into adherent and nonadherent groups on the basis of electronic monitoring or pill count (at least 80% adherent), neither physicians nor patients identified adherent behavior (kappa≤20. Therefore, although the percentages of patients identified as adherent by physicians and electronic monitoring were similar, the two methods identified different patients as adherent.

|

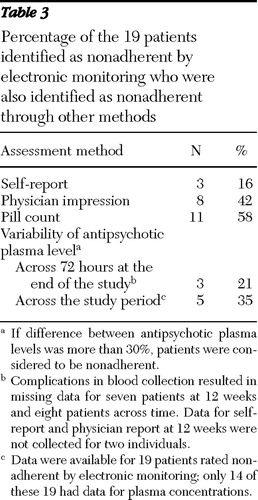

According to electronic monitoring, 19 patients were nonadherent. We determined the percentage of these 19 who were also identified as nonadherent by patient self-report, physician impression, pill count, and antipsychotic plasma level. These results appear in Table 3 and suggest that pill count identifies the greatest number of nonadherent patients (11 patients, or 58%), and self-report identifies the fewest (three patients, or 16%). Physicians identified 42% of nonadherent patients (eight patients).

|

None of the adherence measures correlated significantly with psychotic symptoms, but physician impression and self-report were weakly related to Clinical Global Impression in the expected direction (r k =-.25, p<.03, and r k =-.27, p<.02, respectively) None of the relationships were significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. No significant relationships between change in clinical state across the 12 weeks and adherence measures were found.

Discussion

There was strong agreement between electronic monitoring and pill count when using rank-order correlations. Moreover, these two measures demonstrated the strongest agreement when the sample was dichotomized into adherent and nonadherent groups by using an 80% cutoff. However, agreement between these methodologies was not perfect. This may in part be related to a number of patients having adherence scores close to 80%. In addition, measurement problems including leaving the electronic cap off the bottle, taking more than one pill out of the bottle at a time, and taking medication out of other bottles can contribute to disagreement among these two measures. Although many studies report high levels of missing data with electronic monitoring and pill counts, collecting these data in the participants' homes resulted in few missing observations ( Table 1 ).

Antipsychotic plasma levels were not correlated with any other measure of adherence. It is possible that antipsychotic plasma levels were affected by the behavior of the patient in the days immediately preceding the blood draws, whereas pill counts and electronic monitoring data were averaged across the 12 weeks. A patient could miss doses before a blood draw and be identified as poorly adherent by the levels of antipsychotic in the plasma, even though over a three-month period the individual had taken more than 80% of his or her medication.

These results may call into question the use of data on antipsychotic plasma levels to provide more than a presence or absence classification for adherence to oral antipsychotic medications. Using presence versus absence is not effective for identifying poorly adherent patients who are taking at least some medication. In the study presented here, all participants tested had detectable levels of antipsychotic or active metabolite in their blood even though by other objective measures, 35% were not taking a therapeutic dosage of medication. Problems that arise from using data on antipsychotic plasma levels for anything other than a presence or absence classification include changes in concomitant medications, diet, or smoking that may affect metabolism; the fact that antipsychotic plasma levels are influenced primarily by pill-taking behavior in the several days immediately before the draw; and the timing of dose the day before the draw. In a study of olanzapine, antipsychotic plasma levels were determined but not used as the primary measure of adherence because there are few data about therapeutic blood levels to use as a criterion ( 31 ). In a recent review, we suggested that unless more sophisticated techniques become available to understand data on plasma concentration levels for different second-generation antipsychotic medications, this method may not be very useful as an adherence measure, particularly for partially adherent patients ( 20 ).

Our results underscore the tendency for self-report to inflate estimates of adherence. Less than 16% of patients (three of 19 patients) identified as nonadherent by electronic monitoring rated themselves as being nonadherent. Relying on the report of the patient is likely to provide unreliable data on adherence. The moderate correlation between patient self-report and physician impression of adherence suggests that the physician may be getting adherence information in part from the patient and using it to make his or her judgment.

Results of the study presented here suggest that to a limited extent patients who say that they take more medication probably take more medication than patients who say that they take less medication. In addition, to a limited extent, physicians can tell which patients may be taking more or less medication. Unfortunately, they are unable to identify which patients are taking what is typically considered to be a therapeutic dosage of medication.

This inability of physicians to discern which patients are taking a therapeutic dosage can lead to problems in prescribing—including unnecessarily adding adjunctive medication, increasing the dosage of medication, or changing the patient to a different antipsychotic—when problem adherence is the real issue. This process may result in the identification of patients who are poorly adherent as being treatment resistant. If, on the other hand, a physician mistakenly assumes that a patient who is doing poorly is poorly adherent, the physician may fail to make necessary changes in the medication regimen.

It appears from these data that, to some extent, physicians and patients assume that patients who are doing better are taking more of their medication than patients who are doing more poorly. Relationships between clinical state and objective measures of adherence were not statistically significant. No measure was related to the severity of positive symptoms. The study may have been too short and had too few participants to detect a relationship between symptoms and adherence. In large-scale studies even brief gaps in the availability of medications has been found to increase the risk of hospitalization ( 2 ).

If the clinical state of partially adherent patients is not significantly related to how much of the prescribed medication is taken, it raises the possibility that we may not be prescribing the medications in the right dosage. Certain patients may do well on half of their prescribed dosage, whereas others who are taking a majority of their prescribed medication may need dosage increases. Without good data on adherence it is very difficult for a provider to identify the correct dosage of the correct medication for a specific patient. It is likely that regimens were developed and adjusted in an environment of partial adherence in which it was not possible for the physician to tell the difference between an ineffective medication and consumption of half of the prescribed dose. The correlation between physician impression and clinical state is likely to be due to a physician's reliance on how the patient is doing to estimate adherence behavior. This type of backward reasoning suggests that physicians may not have the relevant data needed to make informed decisions about prescribing. Patient outcomes are likely to be favorably affected by prescribing guidelines only to the extent that the patient is taking medication as prescribed. By improving patient adherence to medication and physician adherence to prescribing guidelines, real improvements in clinical outcome may be able to be realized.

These findings must be interpreted in the context of the methodological weaknesses of the study. The sample was relatively small. Moreover, home visits and adherence assessment may have influenced adherence behavior. Selection bias may have resulted in more adherent patients entering the trial. Pill counts and electronic monitoring data may have been most highly correlated because information came from the same source (bottle). Finally, electronic monitoring, although arguably a best standard against which to judge other measures of adherence, is not perfect. Despite methodological limitations, the findings are important in understanding adherence data from a variety of sources.

Conclusions

Better ways to assess and treat problem adherence are needed. Without accurate information on how much of the prescribed medication an individual is taking, treating physicians may be making decisions in the dark about how to change or add medications. Utilizing new technologies, such as smart pill containers capable of prompting adherence, measuring adherence, and downloading adherence information to a secure Web site that can be checked by treatment providers, may get needed data to prescribers ( 20 ). With the rising cost of medication treatments and the costly investment in the development of new medications, maximizing adherence should be a primary goal for community mental health.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors were supported in part during the preparation of the manuscript by grants R01-MH-61775-04 and R01-MH-62850-05 from the National Institute of Mental Health. This was an investigator-initiated study sponsored by Janssen, LP. The authors thank the investigators and staff at Tri-County Community Mental Health and Mental Retardation Clinic in Conroe Texas and El Paso Community Mental Health and Mental Retardation Center.

Dr. Velligan is a consultant for and has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer and is a consultant for InforMedix. Dr. Miller is a consultant for and has received research support from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer and has received research support from Alexza, Eli Lilly, Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Solvay. Dr. Ereshefsky and California Clinical Trials conduct clinical trials for multiple pharmaceutical companies. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Velligan DI, Lam F, Ereshefsky L, et al: Psychopharmacology: perspectives on medication adherence and atypical antipsychotic medications. Psychiatric Services 54:665–667, 2003Google Scholar

2. Weiden P, Glazer W: Assessment and treatment selection for "revolving door" inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly 68:377–392, 1997Google Scholar

3. Valenstein M, Copeland L, Owen R, et al: Adherence assessments and the use of depot antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62:545–551, 2001Google Scholar

4. Serban G, Thomas A: Attitudes and behaviors of acute and chronic schizophrenic patients regarding ambulatory treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 131:991–995, 1974Google Scholar

5. Sackett DL, Haynes RB: Compliance With Therapeutic Regimens. Baltimore, Md, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976Google Scholar

6. Sullivan G, Wells KB, Morgenstern H, et al: Identifying modifiable risk factors for rehospitalization: a case-control study of seriously mentally ill persons in Mississippi. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1749–1756, 1995Google Scholar

7. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:637–651, 1997Google Scholar

8. Weiden P, Rapkin B, Zygmunt A, et al: Postdischarge medication compliance of inpatients converted from an oral to a depot neuroleptic regimen. Psychiatric Services 46:1049–1054, 1995Google Scholar

9. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al: Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 353:1209–1223, 2005Google Scholar

10. Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK: Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatric Services 52:805–811, 2001Google Scholar

11. Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al: Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 55:886–891, 2004Google Scholar

12. Nakonezny PA, Byerly MJ: Electronically monitored adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a comparison of first- vs second-generation antipsychotics. Schizophrenia Research 82:107–114, 2006Google Scholar

13. Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al: Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:692–699, 2004Google Scholar

14. Menzin J, Boulanger L, Friedman M, et al: Treatment adherence associated with conventional and atypical antipsychotics in a large state Medicaid program. Psychiatric Services 54:719–723, 2003Google Scholar

15. Constantine R, Richard S, Surles R: Optimizing pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia: tools for the psychiatrist. Current Psychosis Therapeutics Reports 4:5–11, 2006Google Scholar

16. Miller AL, Crismon ML, Rush AJ, et al: The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: clinical results for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:627–647, 2004Google Scholar

17. Miller AL, Hall CS, Buchanan RW, et al: The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2003 update. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:500–508, 2004Google Scholar

18. Miller AL: PORT treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:601–604, 2004Google Scholar

19. Eaddy M, Grogg A, Locklear J: Assessment of compliance with antipsychotic treatment and resource utilization in a Medicaid population. Clinical Therapeutics 27:263–272, 2005Google Scholar

20. Velligan DI, Lam YW, Glahn DC, et al: Defining and assessing adherence to oral antipsychotics: a review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:724–742, 2006Google Scholar

21. Byerly M, Fisher R, Whatley K, et al: A comparison of electronic monitoring vs clinician rating of antipsychotic adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 133:129–133, 2005Google Scholar

22. Byerly MJ, Thompson A, Carmody T, et al: Validity of electronically monitored medication adherence and conventional adherence measures in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 58:844–847, 2007Google Scholar

23. Ventura J, Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, et al: Manual for the Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 3:227–244, 1993Google Scholar

24. De Leon J: Atypical antipsychotic dosing: the effect of co-medication with anticonvulsants. Psychiatric Services 55:125–128, 2004Google Scholar

25. Riedel M, Schwarz MJ, Strassnig M, et al: Risperidone plasma levels, clinical response and side-effects. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 255:261–268, 2005Google Scholar

26. Perel JM: Compliance during tricyclic antidepressant therapy: pharmacokinetic and analytical issues. Clinical Chemistry 34:881–887, 1988Google Scholar

27. Dugan DJ, Ereshefsky L, Toney GB, et al: Dose and interval adherence among stabilized clozapine-treated patients measured by medication event monitoring. Presented at the Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit, Boca Raton, Florida, May 30–June 2, 2000Google Scholar

28. Kay S: Positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: assessment and research. Clinical and Experimental Psychiatry Monograph 5:1–283, 1991Google Scholar

29. Velligan DI, Prihoda TJ, Dennehy EB, et al: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Expanded Version: how do new items affect factor structure? Psychiatry Research 135:217–228, 2005Google Scholar

30. Farmer KC: Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clinical Therapeutics 21:1074–1090, 1999Google Scholar

31. Kinon B, Hill AL, Liu H, et al: Olanzapine orally disintegrating tablets in the treatment of acutely ill noncompliant patients with schizophrenia. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 6:97–102, 2003Google Scholar