Best Practices: The Consultation-Liaison in Primary-Care Psychiatry Program: A Structured Approach to Long-Term Collaboration

Internationally, the ascendance of community care has increased general practitioner involvement in caring for people with serious and chronic mental illnesses ( 1 , 2 ). In Australia about 75% of general practitioners care for patients with schizophrenia ( 3 ), a situation that might provide opportunities for health promotion and the treatment or care of physical illnesses common among these patients ( 4 ). More generally, care provided by general practitioners may be more accessible ( 5 ) and lack stigma associated with specialist services ( 1 ). Also, treatment by local general practitioners may encourage the community reintegration of people with long-term mental illnesses.

However, general practitioners have limited capacity for assertive follow-up ( 5 ) and often lack confidence in managing psychotic disorders ( 3 ). Poor relationships between specialists and general practitioners and limited support from specialist services to general practitioners are barriers to the successful treatment of serious mental illnesses in primary care ( 3 ). Although involvement in the management of chronic mental illness by general practitioners has benefits, proper treatment requires well-identified pathways to specialist support. Empirical evidence to guide best practices in the collaborative management of chronic psychiatric illness in primary care settings is limited ( 5 ).

CLIPP: an Australian shared care model

Australian mental health care has three major sectors with different constraints. State-funded community mental health services receive block funding for salaried staff, and this funding level is the primary constraint to their clinical capacity. A private primary care and outpatient specialist sector, heavily financially supported by fee-for-service rebates from the federal government, is constrained by available workforce and permitted rebates. Finally a nongovernmental insurance sector is constrained by number of insured participants and different allowable benefits. Developed in Melbourne within this context, the Consultation-Liaison in Primary-Care Psychiatry (CLIPP) model ( 5 , 6 ) draws on liaison ( 2 ) and consultation-liaison ( 7 ) approaches to primary care psychiatry, but the synthesis is novel, as are other aspects of the model. Protocols are available at www.health.vic.gov.au/mentalhealth/publications/clipp.

Consultation-liaison

The first component of CLIPP is a consultation, liaison, and education service. Consultation-liaison attachments to participating general practice groups (three to ten general practitioners per group) involve a half-day psychiatrist visit every two weeks. Psychiatrists provide support by assessing patients referred by general practitioners and see two to three referred patients per consultation session. This process allows general practitioners to provide management supported by a specialist consultation, with specialist support provided again if necessary.

Medicare Benefit Schedule reimbursements are entitlements for all Australian citizens or permanent residents and are assigned by the patient to the treating private practitioner. Copayment is at the discretion of the practitioner and often is waived in cases of hardship. Progressive changes in the Medicare Benefit Schedule have encouraged the kind of collaborative work described here. Following recent changes in the Medicare Benefit Schedule, general practitioners can claim Medicare Benefit Schedule treatment-planning and case-conferencing items. The Medicare Benefit Schedule also now pays psychiatrists for shared-care treatment planning in private practice. Since November 2006 there is a recommended fee of AU $400 (U.S. $326) for an assessment and treatment plan provided to the general practitioner, with 85% of this paid for by Medicare. Psychiatrists in CLIPP schemes have typically been salaried by the state community mental health center, but these recent Medicare changes may facilitate more such work in the private sector.

Structured CLIPP documentation assists quality control of the consultancy process. A reminder system requests information on clinical course from the general practitioner three months after these consultations; adverse outcomes are flagged for review by the psychiatrist ( 6 ).

Transfer into shared care

The second component of CLIPP involves the transfer of selected patients from state-funded community mental health services into collaborative care with the private sector. A designated nurse associated with community mental health services actively identifies cases suitable for transfer, then engages with case managers and psychiatrists to support prospective candidates for transfer. These candidates are typically people with a degree of insight and social support and whose disorder is clinically stable. Without a shared-care arrangement their care might involve discharge to a general practitioner without specialist support, with attendant risks of loss to follow-up and progressive clinical deterioration. Alternatively, continuing attendance at community mental health services may carry some institutional stigma, and the individuals consume resources from a capacity-constrained system that otherwise could be available to respond to the needs of new consumers more in need of specialist care. For many patients the prospect of transfer into the CLIPP program has proved to be an attractive one.

At a case conference in the primary care clinic, transfer of care is supported by a detailed management plan prepared by mental health service staff, including the CLIPP nurse, and designed with the needs of the general practitioner in mind; the general practitioner then takes over direct clinical management. Reviews by the visiting psychiatrist ( 6 ), taking an average of one hour per year after the general practitioner assumes responsibility for patient care, are scheduled in the same half-day visits that provide for the consultation-liaison service.

Management plans are based on a relapse signature-relapse drill structure. Described as "a set of general and idiosyncratic symptoms, occurring in a specific order, over a particular time period, that serve as early warning signs of impending … relapse" ( 8 ), the relapse signature as set out in the management plan is used by the participating general practitioners to structure patient reviews. If indications of relapse are present, the relapse drill provides a concrete action plan for preventive intervention ( 5 , 8 ).

Maintaining continuity

Effective retention in general practitioner-based collaborative care of good quality is the goal of the final component of CLIPP in which the specialist mental health service retains a supervisory stance. An administrative staff member maintains office systems by using standard software that provides regular clinician reminders and recall systems that can be tailored to an extent for particular patients. Generally, attendance is monitored every three months. Regular phone calls to assess patient satisfaction are made once every three months at the start but then are reduced in frequency once the transfer arrangement appears stable. Psychiatrist reviews are prompted every six to 12 months. If emergent problems indicate an outreach approach beyond the general practitioner's capability, then the CLIPP nurse can attend for awhile. In these situations there needs to be close communication with the psychiatrist and general practitioner and ready return back into community mental health services care if prolonged or intensive community treatment is needed.

Is collaborative care quality care?

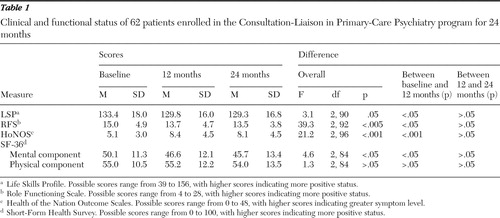

Sixty-two patients with a range of major psychiatric disorders, most commonly schizophrenia, transferred over a period of two years from specialist outpatient management into CLIPP care were, for two years after transfer, observed in a study approved by the local Research and Ethics Committee. They were observed for two years after transfer. Outcome measures used were the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) ( 9 ), the Life Skills Profile (LSP) ( 10 ), the Role Functioning Scale (RFS) ( 11 ), and the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) ( 12 ). All patients transferred within the program judged able to provide informed consent were invited to participate (N=86), and 62 (76%) of these participated.

Data were gathered before the transfer and at 12 and 24 months post-transfer (plus or minus one to two months). The data analyzed combined routinely collected clinical data with data collected by the research team. Informed consent was obtained for use of data. Repeated-measures analyses of variance were employed to assess for differences in outcome measures between time points. Where overall differences were identified, post hoc tests of contrasts were undertaken between scores at inception and 12 months and between scores at 12 months and 24 months.

Table 1 summarizes these analyses. Between transfer into shared care and 12-month follow-up, there was some decline in group clinical status as measured by decreased mean scores on the RFS, LSP, and SF-36 mental component, with some increase in total HoNOS symptom scores. The changes were generally modest in scale. For instance, although the LSP has a suggested threshold for clinically significant score change of 18, the mean change measured here was below 4. Between 12 and 24 months, there were no appreciable differences in scores on any measures. LSP scores throughout the 24 months remained above the level typically indicating need for more intensive support ( 13 ).

|

At transfer to CLIPP this sample had high general functioning scores compared with those of in a similar patient group ( 13 ). Clinical stability was one of the requirements for selection for transfer, and the model aims to transfer patients when they are at their clinical "personal best." Although the results indicate some reduction in clinical status and function over the first 12 months in CLIPP, such changes appear to be modest. They might reflect selection bias for transfer at a relatively clinical high point, although adjustment to new care arrangements that are less intensive than those provided by community mental health services may also contribute to the observed changes. These data suggest that any actual deterioration was not progressive beyond the first year, with clinical status and functioning remaining stable between 12 and 24 months after transfer.

Conclusions

Health care system variability is such that this model will not generalize to all settings, but where implemented, the CLIPP model sets up a two-way street between primary and specialist service sectors. For individuals this allows flexible matching of the patient and the model of care. For the health care system this allows the service sectors to better collaborate in sharing the clinical workload arising from the local population. Observational findings, although not yet confirmed by more robust research designs, suggest that there is not a substantial or continuing clinical or functional deterioration after transfer from specialist management to collaborative care managed by general practitioners under CLIPP processes. The model provides an accessible template for collaboration and management processes that may enhance the capacity of the primary care sector to manage people with serious mental illnesses in the community.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The development of this clinical program was supported by the Department of Human Services, Victoria, Australia, with specific clinical services providing funding, including Melbourne Health and Werribee Mercy hospitals. Evaluative activities were supported by the Commonwealth Government of Australia General Practice Evaluation Program through grant 518.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Copolov D: Psychoses: a primary care perspective. Medical Journal of Australia 168:129–135, 1998Google Scholar

2. Nazareth ID, King MB: Schizophrenia: community care and the family physician. International Review of Psychiatry 4:267–271, 1992Google Scholar

3. Carr VJ, Lewin TJ, Barnard RE, et al: Attitudes and roles of general practitioners in the treatment of schizophrenia compared with community mental health staff and patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 39:78–84, 2004Google Scholar

4. Beecroft N, Becker T, Griffiths G, et al: Physical health care for people with severe mental illness: the role of the general practitioner (GP). Journal of Mental Health 10:53–61, 2001Google Scholar

5. Meadows GN: Overcoming barriers to reintegration of patients with schizophrenia: developing a best-practice model for discharge from specialist care. Medical Journal of Australia 178:S53–S56, 2003Google Scholar

6. Meadows GN: Establishing a collaborative service model for primary mental health care. Medical Journal of Australia 168:162–165, 1998Google Scholar

7. Strathdee G, McDonald E: Innovations: Establishing psychiatric attachments to general practice: a six stage plan. Psychiatric Bulletin 154:72–76, 1992Google Scholar

8. Birchwood M, Spencer E, McGovern D: Schizophrenia: early warning signs. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 6:93–101, 2000. Available at www.iris-initiative.org.uk/earlysigns.pdfGoogle Scholar

9. Wing J: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales: HoNOS Field Trials. London, Royal College of Psychiatrists Research Unit, 1994Google Scholar

10. Rosen A, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Parker G: The Life Skills Profile: a measure assessing function and disability in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:325–337, 1989Google Scholar

11. Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, et al: Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale. Community Mental Health Journal 29:119–131, 1993Google Scholar

12. Ware JE, Sharbourne CD: The MOS Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): 1. conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30:473–483, 1992Google Scholar

13. Trauer T, Duckmanton RA, Chiu E: The assessment of clinically significant change using the Life Skills Profile. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 31:257–263, 1997Google Scholar