Treatment Adherence With Lithium and Anticonvulsant Medications Among Patients With Bipolar Disorder

Lithium has long been a cornerstone of treatment for individuals with bipolar disorder because of its demonstrated efficacy in managing acute mood episodes, preventing relapse, reducing subthreshold symptoms, and reducing suicide risk ( 1 , 2 ). Over the past decade additions to the therapeutic armamentarium for bipolar disorder have included valproate or divalproex, newer anticonvulsant medications, and second-generation antipsychotic compounds ( 1 , 3 ). Although expansion of treatment options offers the potential for improving outcomes, treatment nonadherence remains a persistent problem ( 4 , 5 , 6 ).

Two recent reviews of studies evaluating medication nonadherence among patients with bipolar disorder found median rates of nonadherence of 41% ( 7 ) and 42% ( 4 ). In comparison, rates of adherence with medication in mixed psychiatric patient populations range from 24% to 87%, with a mean of 52% ( 8 ). The reasons for treatment nonadherence appear multidimensional, involving symptoms of bipolar illness, psychiatric and substance use comorbidities, and patient attitudes toward treatments and medications ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ).

Research on medication treatment adherence has predominantly focused on side effects and tolerability ( 13 , 14 , 15 ). Some investigators have suggested that adherence with lithium is worse than adherence with valproate ( 14 ). An issue of growing importance is the increasing emphasis on polytherapy as a component of best practices for treatment of bipolar disorder ( 3 ). How this might affect treatment adherence is not clear, because the use of multiple agents is likely to increase potential for adverse effects and possible drug-drug interactions. Some researchers have found that the use of multiple agents to stabilize mood is associated with greater nonadherence ( 15 , 16 ). However, others have not found that polytherapy is associated with increased rates of nonadherence ( 17 ).

This study examined treatment adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant medications among individuals with bipolar disorder treated in Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) settings during federal fiscal year 2003 (FY03; October 1, 2002, through September 30, 2003); rates of adherence among patients who were treated with more than one agent, compared with those treated with only one agent; patient predictors of adherence; and associations between poor adherence and subsequent hospitalization. Veterans with bipolar disorder are predominantly male and have relatively high rates of comorbidity, including substance use disorders ( 18 ), factors generally associated with lower adherence. We hypothesized that poor adherence with lithium and anticonvulsants would be common, patients taking multiple mood stabilizers would have lower rates of adherence, and lower adherence rates would be associated with increased rates of hospital admission.

Methods

Participants

The database from which study results are derived, the National Psychosis Registry (NPR), is an ongoing registry of all veterans diagnosed as having psychosis in VA treatment settings from 1988 to the present. Pharmacy data from the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group are also incorporated in the registry.

We identified patients with a bipolar diagnosis in the NPR using ICD-9-CM codes 296.0, 296.1, 296.4, 296.5, 296.6, 296.7, and 296.8. Individuals were included if they had at least one qualifying diagnosis during FY03. In the event that patients received more than one diagnosis over time, individuals were assigned to the diagnosis that appeared in the greatest number of episodes of care during FY03. Ties were resolved by using a rank ordering of schizophrenia (first), bipolar disorder (second), and other psychosis (third). Anticonvulsants included in study analyses were valproate or divalproex, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine. The total sample consisted of 44,637 patients.

Measurement of adherence

Medication adherence was evaluated by using the medication possession ratio (MPR) for patients receiving lithium or anticonvulsant medication during FY03. The MPR is the ratio of the number of days' supply of medication that a patient has received divided by the number of days' supply that they should have received had they been taking medication as prescribed. Number of days' supply that should have been received was based on timing of medication refills, such that sufficient drug was dispensed if it could be taken daily without interruption. An MPR of 1.00, or 100%, indicates that the patient has received all medication needed to take antipsychotic medication as prescribed, whereas an MPR of .50, or 50%, indicates that the patient has received medication sufficient to take only half of the prescribed dosage.

The MPR was calculated for patients with at least 90 days of observation time during the study period. The MPR was calculated for the period of FY03 after the date of the patient's first lithium or anticonvulsant prescription fill of the year. Days spent in institutional settings were subtracted from the numbers of days' supply the patient should have received in order to take his or her medication as prescribed. In cases in which an individual was on more than one anticonvulsant medication or on both lithium and an anticonvulsant, a weighted average of the MPRs for the two drugs was calculated. MPR calculations were limited to individuals who were taking no more than two medications relevant to the analysis. The MPR, a measure of prescription refills, has been widely utilized in both medical and psychiatric settings as a proxy measure of treatment adherence ( 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ), including assessment of adherence in populations with serious mental illness and in bipolar populations specifically ( 24 , 25 ).

Adherence intensity

Individuals who were fully adherent with antipsychotic medication had MPRs higher than .80. Individuals who were partially adherent with antipsychotic medication had MPRs from more than .50 to .80. Individuals who were considered to be nonadherent with medication (proportion of medication taken was so minimal, it was unlikely to have the desired therapeutic effect) had MPRs of .50 or less. Similar methods for categorizing ordinal level of adherence among patients with serious mental illness, including bipolar disorder, have been used by a number of investigator groups ( 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ). Unlike some other previous reports ( 21 ), a maximum ratio of 1.00 was not applied, because doing so would bias comparisons against agents with a relatively high adherence intensity. Although MPRs greater than 1.00 may also reflect overprescribers ( 26 ), this cannot be determined solely from claims data. For example, MPRs greater than 1.00 were possible in cases in which prescriptions may not have been completely used because of an interim change in dosage.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with bipolar disorder who were given prescriptions for lithium, anticonvulsant medication, or both. Multinomial multiple logistic regression was used to compare demographic and clinical characteristics of patients given prescriptions for lithium without anticonvulsants, anticonvulsants without lithium, or both medications and to compare demographic characteristics, hospitalization rates, and hospital length of stay for patients with full adherence, partial adherence, or nonadherence to lithium or anticonvulsant medication. Sex, age, race, marital status, substance use disorder, comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and homelessness were included as covariates in the models. Models comparing demographic characteristics also controlled for number of outpatient psychiatric visits during the year. Models comparing hospitalization rates and hospital length of stay among patient groups controlled for psychiatric hospitalization in the previous year and number of outpatient psychiatric visits. Hospital stay analysis included only patients who had hospitalizations during the study period. Wilcoxon tests were used to compare the mean MPR for patients receiving one versus two medications and the mean MPR for patients receiving lithium versus a single anticonvulsant. MPRs for patients on a single medication were compared by drug, by using analysis of variance with a Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Results

Lithium and anticonvulsant group differences

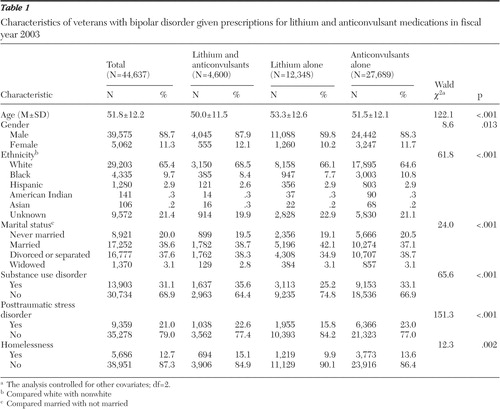

Table 1 outlines the characteristics of individuals given prescriptions for lithium and anticonvulsant medication. Among individuals who received lithium or anticonvulsant medication, 62.0% (N=27,689) were given prescriptions for anticonvulsant medication without lithium, whereas 27.7% (N=12,348) were given prescriptions for lithium without anticonvulsant medication.

|

When the analyses controlled for other covariates in the multinomial logistic regression model, compared with patients given prescriptions for both lithium and anticonvulsant medication, individuals who were given prescriptions for lithium alone were more likely to be older (Wald χ2 =121.4, df=1, p<.001) and nonwhite (Wald χ2 =6.6, df=1, p=.010) and had illness uncomplicated by substance abuse (Wald χ2 =39.2, df=1, p<.001), PTSD (Wald χ2 =41.4, df=1, p<.001) or homelessness (Wald χ2 =11.6, df=1, p<.001). Compared with patients given prescriptions for both lithium and an anticonvulsant, individuals given prescriptions for an anticonvulsant alone were more likely to be older (Wald χ2 =86.9, df=1, p<.001) and nonwhite (Wald χ2 =43.2, df=1, p<.001) and were less likely to be married (Wald χ2 =13.7, df=1, p<.001) or homeless (Wald χ2 =4.0, df=1, p=.047).

This sample of patients with bipolar disorder was given prescriptions not only for lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, or lamotrigine; they also received other psychotropic medications, including antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and other antianxiety medications, antipsychotics, stimulants, and anticholinesterases. Patients treated with both lithium and anticonvulsant medication received a slightly higher number of supplemental psychotropic medications on average (2.9 additional medications versus 2.6 for patients taking anticonvulsants only and 2.1 for those taking lithium only; Kruskal-Wallis χ2 =1,089.4, df=2, p<.001).

Although differences between groups prescribed lithium alone, anticonvulsants alone, or lithium and anticonvulsant combination therapy were statistically significant, these differences were quite modest and of unclear clinical significance.

Treatment adherence

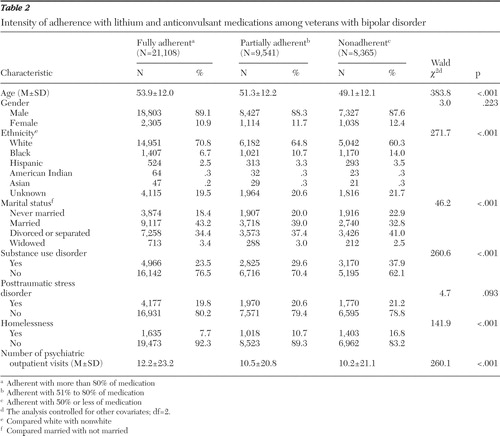

Table 2 demonstrates intensity of adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant medications. Overall, 54.1% of individuals (N=21,108) were fully adherent with medications, 24.5% (n=9,541) were partially adherent, and 21.4% (N=8,365) were nonadherent.

|

Compared with fully adherent individuals, individuals who were nonadherent tended to be younger (Wald χ2 =336.7, df=1, p<.001), nonwhite (Wald χ2 =243.8, df=1, p<.001), unmarried (Wald χ2 =45.0, df=1, p<.001), and homeless (Wald χ2 =140.3, df=1, p< .001) and to have a substance use disorder (Wald χ2 =250.4, df=1, p<.001), PTSD (Wald χ2 =4.4, df=1, p=.036), and fewer psychiatric outpatient visits (Wald χ2 =213.4, df=1, p<.001). Rates of nonadherence among ethnic groups were 17.3% among whites (5,042 of 29,203 whites), 27.0% among blacks (1,170 of 4,335 blacks), 22.9% among Hispanics (293 of 1,280 Hispanics), 16.3% among American Indians (23 of 141 American Indians), and 19.8% among Asians (21 of 106 Asians).

Compared with the combined group of fully and partially adherent patients, patients who were nonadherent were more likely to be younger (Wald χ2 =245.6, df=1, p< .001), nonwhite (Wald χ2 =158.1, df=1, p<.001), unmarried (Wald χ2 =37.3, df=1, p<.001), and homeless (Wald χ2 =129.7, df=1, p<.001) and to have a diagnosis of substance use disorder (Wald χ2 =193.0, df=1, p<.001) and fewer psychiatric outpatient visits (Wald χ2 =156.6, df=1, p<.001).

Adherence with specific compounds

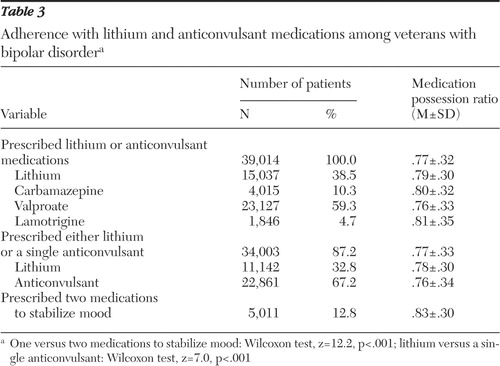

Table 3 outlines use and MPRs of lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine. Valproate was the most commonly prescribed anticonvulsant medication (received by 59% of patients with bipolar disorder). MPRs across agents ranged from .76 for valproate to .81 for lamotrigine. Among patients taking a single medication, the mean MPR for valproate was lower (.75±.34) (F=22.8, df=3, 33,999, p<.001; Tukey's HSD p<.05) than the MPRs for lithium or other anticonvulsants. The mean MPR for patients on valproate was .75±.34 versus .78±.31 for patients taking lithium or another anticonvulsant (Wilcoxon z=9.96, p<.001). Individuals who were taking two medications to stabilize mood also had significantly higher levels of adherence than patients taking only one medication (Wilcoxon z=12.2, p<.001).

|

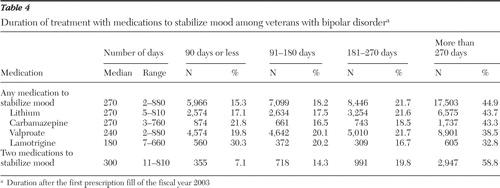

The duration of medication treatment is outlined in Table 4 . Treatment duration was greater than 180 days for a majority of patients, except for individuals treated with lamotrigine.

|

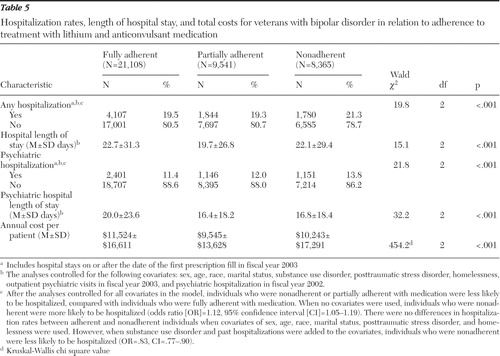

Health resource utilization

Table 5 demonstrates hospitalization rates, length of stay, and costs for individuals with bipolar disorder in relation to adherence. Total costs included inpatient, outpatient, and prescription costs. After the analyses controlled for patient characteristics, individuals who were nonadherent or partially adherent with medication were less likely to be hospitalized than individuals who were fully adherent (Wald χ2 =19.8, df=2, p<.001 and Wald χ2 =21.8, df=2, p<.001, respectively, for any hospitalization and psychiatric stays). Substance use disorder and previous hospitalizations appeared to be the major predictors of hospitalization. After the analysis controlled for adherence and other covariates in the model, among patients taking lithium or anticonvulsants, the odds ratios for hospitalization were .88 (95% confidence interval [CI]=.80–.97) for men compared with women, 1.19 (CI=1.15–1.21) for each ten-year increase in age, 1.09 (CI=1.01–1.18) for nonwhites compared with whites,1.04 (CI=.98–1.11) for unmarried individuals compared with married individuals, 3.24 (CI=3.03–3.46) for individuals with a substance use disorder compared with those without such a disorder, 1.37 (CI=1.28–1.47) for individuals with PTSD compared with those without PTSD, 2.02 (CI=1.85–2.19) for homeless individuals compared with those who were not homeless, and 2.73 (CI=2.55–2.92) for individuals with a previous hospitalization compared with those without a previous hospitalization.

|

Individuals who were adherent with medication also had longer hospital stays (mean of 22.7±31.3 days) compared with those who were partially adherent (mean of 19.7±26.8 days) and those who were nonadherent (mean of 22.1±29.4 days) (Wald χ2 =15.1, df=2, p<.001). Nonadherent patients were more likely to have irregular hospital discharge codes (10.8% of discharges for nonadherent patients, compared with 4.5% of discharges for fully adherent patients and 7.0% of discharges for partially adherent patients).

Finally, as demonstrated in Table 5 , fully adherent patients had the highest total costs on average ($11,524, compared with $9,545 for partially adherent patients and $10,243 for nonadherent patients; Kruskal-Wallis χ2 =454.2, df=2, p<.001).

Discussion

This naturalistic study indicates that nonadherence with medications is common among individuals with bipolar disorder ( 5 , 6 ). Only a slight majority (54.1%) of patients with bipolar illness were fully adherent with lithium or anticonvulsant medication, with a substantial proportion of individuals being only partially adherent with medication (24.5%) or nonadherent (21.4%). Our findings on adherence from this very large database include the use of the novel anticonvulsant lamotrigine in addition to traditional older mood stabilizers (lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine) and are consistent with estimates from older databases on bipolar treatment adherence that do not include the newest treatment agents ( 10 , 13 ). Our results emphasize the point that adherence rates are not higher with newer, theoretically better-tolerated agents and that, in fact, adherence rates are rather similar across mood-stabilizing compounds. The clinical implications are striking—with nearly one in two individuals in treatment for bipolar disorder not taking medications as prescribed, nonadherence must be considered in treatment planning on a regular and ongoing basis.

Previous authors have noted inconsistent findings with respect to treatment nonadherence predictors ( 15 , 16 , 29 , 30 ), although most studies have found that younger age and single status or living alone appear to be associated with increased rates of nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder ( 4 ). Our study found that nonadherent individuals were younger, unmarried, and of minority ethnicity. Across groups of varying ethnicity, the highest proportion of nonadherent individuals were black (27.0%). Among whites the proportion of nonadherent individuals was 17.3%. Although our study also found relatively low rates of nonadherence among American Indians (16.3%), these results should be interpreted with caution because of the small sample of nonadherent American-Indian individuals (N=23). Minority ethnicity has been noted to be associated with reduced treatment adherence in populations with bipolar disorder ( 4 ). Additionally, nonadherent individuals had fewer psychiatric outpatient visits and more substance use disorder, PTSD, and homelessness. The latter finding is consistent with several previous studies ( 12 , 14 , 29 ).

In our analysis adherence intensity was slightly lower for valproate, compared with lithium or other anticonvulsants. In contrast, Revicki and colleagues ( 31 ) recently noted that among individuals with bipolar I disorder, divalproex-treated patients were less likely than lithium-treated patients to discontinue study medications. However, patients in the trial by Revicki and colleagues ( 31 ) were participating in a pragmatic, clinical trial, and this might account for the differences in apparent tolerability of valproate in that study, compared with the VA population presented in our study. Although much has been made of adverse medication effects as a barrier to optimal treatment adherence ( 4 ) and it is likely that adverse effects are clearly a reason for nonadherence for some individuals, there are other reports in the bipolar treatment literature suggesting that rates of adherence are remarkably similar across agents, including drug classes with vastly differing side effect profiles and differing mechanisms of action ( 4 , 32 ). Thus it is likely that medication side effects are just one component that may or may not be a deciding factor for an individual to adhere to a specific treatment regimen. The current data set did not permit an evaluation of reasons for nonadherence; however, previous work by this group of investigators suggests that treatment nonadherence is not simply a "patient problem," but rather reflects a key ingredient of the provider-patient relationship ( 33 , 34 ).

In our study individuals who were given a prescription for two agents to stabilize mood (which theoretically might increase side effects) had better treatment adherence, compared with individuals given a prescription for a single agent. Potentially, treatment with multiple agents results in greater symptomatic treatment, better attitudes toward the treatment regimen, and ultimately better adherence. Alternatively, clinicians may treat patients with two agents only if they are convinced that patients are adherent with prescribed monotherapy. Multiple drug prescribing could also indicate a more treatment-resistant condition or greater interest and effort on the part of the staff.

In some health care settings, costs for prescriptions can be a potential barrier to treatment adherence with medications. The prescription copayment in the VA system was $7.00 in 2002. Although this could have been a barrier for some individuals, it is relatively low compared with what might be seen in other payer systems.

Duration of treatment data in this analysis suggests that the long-term use of both lithium and anticonvulsant compounds, including the use of polytherapy with mood-stabilizing agents, is common in clinical settings. This practice is supported by recent expert consensus guidelines for the treatment of individuals with bipolar disorder ( 3 ).

Finally and surprisingly, we found that medication nonadherence was associated with decreased rates of hospitalization. Other investigators have reported that lithium discontinuation is associated with increased likelihood of hospital readmission ( 35 , 36 ). It is possible that in our sample the effects of poor adherence on hospitalization might have been mediated through covariates that predicted hospitalization, greater use of substances (diagnosis of substance use disorder), or greater longer-term illness severity (previous psychiatric hospitalization). Lower rates of hospitalization among nonadherent patients may have been due to their refusing hospital admission. The minimally shorter hospital stays among nonadherent patients may have been due to their leaving the hospital prematurely against medical advice. Irregular hospital discharges were most common among the nonadherent group.

Additionally, individuals who were nonadherent with treatment in VA settings may have received care in other settings, such as state hospitals, or have been removed from care settings entirely; for example they may have entered the prison system. Alternatively, increased rates of hospitalization among adherent veterans may reflect greater help-seeking behaviors on the part of these patients. Inpatient care in the VA health care system may be more accessible to patients who seek or request it, compared with inpatient care in other health care systems. Finally, it must be noted that in a very large database such as the one we used, findings that are statistically significant may actually reflect rather small clinical differences, such as in the rates of hospitalization across adherence groups (20% for adherent individuals and 21% for nonadherent individuals in nonadjusted analyses). The impact of these differences in total care needs within bipolar populations is not entirely clear.

Total costs were highest in the adherent group, reflecting the greater use of health care services. Although hospitalizations and direct treatment costs do not appear to be increased among nonadherent individuals, there may be other negative sequelae associated with treatment nonadherence, including increased symptom levels, increases in suicidal behavior ( 37 ), and diminished response to medications that have been previously efficacious ( 38 , 39 ). Other costs may include disruption of personal relationships, loss of self-esteem, and increased stigma associated with symptoms and disability ( 40 , 41 ). Clearly, "costs" of treatment nonadherence extend beyond direct hospital, medication, and outpatient expenses.

A limitation of the study is that with such a large sample, differences between groups or subgroups may be statistically significant, yet not necessarily clinically relevant. There is also the potential for some degree of diagnostic imprecision as a result of the use of the case registry format. Additionally, we note that rates of full adherence observed in this study are based on pharmacy data. Although it is true that the MPR is based on pharmacy refill records and not a measure of actual medication ingestion, rates of adherence with bipolar disorder treatments are similar to findings noted utilizing other methods of adherence assessment ( 4 ). In any case, rates of adherence derived from case registries should be considered the "upper bound" of adherence. Study results are also limited by the relative gender and ethnic homogeneity of the VA population. Additionally, because the mean age in our study population was somewhat older than the mean age of bipolar populations that might be treated in some other settings, results may not be readily extrapolated to younger groups of individuals with bipolar disorder.

Conclusions

Despite the rapid growth of treatments for bipolar disorder that demonstrate generally good efficacy in research settings, the effectiveness of bipolar medication treatments is likely to be reduced by high rates of treatment nonadherence. Some subpopulations of individuals with bipolar illness, such as younger men, persons from minority groups, unmarried individuals, and those with a substance use disorder are at greater risk of treatment nonadherence. Greater attention should be paid to identifying nonadherence among these groups and taking appropriate measures to enhance treatment adherence. This might include such approaches as involving family members to support the individual in adherence behaviors or implementing strategies that fit in with the individual's lifestyle, such as pillboxes, reminder calls, or changes in the timing of medication dosing to accommodate a work or school schedule. Patients, families, and clinicians need to become increasingly aware of the importance of treatment adherence in routine clinical settings, and additional research is needed to develop effective interventions to enhance treatment adherence across the broad range of treatments for bipolar disorder.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Work on this article was supported by grant K23-MH-065599 from the National Institute of Mental Health; grant RCD 98-350 from the Health Services Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; and support from the Serious Mental Illness Treatment, Research, and Evaluation Center, Department of Veterans Affairs, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Dr. Sajatovic has received grants from Bristol- Myers Squibb and Abbott Laboratories; is a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, and Abbott Laboratories; and has received honoraria from AstraZeneca. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder, Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2002Google Scholar

2. Hirschfeld RM, Shea MR: Mood disorders: psychotherapy, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Edited by Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2000Google Scholar

3. Keck PE, Perlis RH, Otto MW, et al: The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Treatment of Bipolar Disorder. A Postgraduate Medicine Special Report Dec:1–116, 2004Google Scholar

4. Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Kacynski R, et al: Medication non-adherence in bipolar disorder: a patient-centered review of research findings. Clinical Approaches in Bipolar Disorders 3:54–56, 2004Google Scholar

5. Schumann C, Lenz G, Berghofer A, et al: Non-adherence with long-term prophylaxis: a 6-year naturalistic follow-up study of affectively ill patients. Psychiatry Research 27:247–257, 1999Google Scholar

6. Greenhouse WJ, Meyer B, Johnson SL: Coping and medication adherence in bipolar disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders 59:237–241, 2000Google Scholar

7. Lingham R, Scott J: Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 150:164–172, 2002Google Scholar

8. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services 49:196–201, 1998Google Scholar

9. Lenzi A, Lazzerini F, Placidi GF, et al: Predictors of compliance with lithium and carbamazepine regimes in the long-term treatment of recurrent mood and related psychotic disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry 22:34–37, 1989Google Scholar

10. Colom R, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, et al: Clinical factors associated to treatment non-compliance in euthymic bipolar patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:549–555, 2000Google Scholar

11. Miklowitz DJ: Longitudinal outcome and medication non-compliance among manic patients with and without mood-incongruent psychotic features. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:703–711, 1992Google Scholar

12. Maarbjerg K, Aagaard J, Vestegaard P: Adherence to lithium prophylaxis. I: clinical predictors and patient's reasons for nonadherence. Pharmacopsychiatry 21:121–125, 1988Google Scholar

13. Scott J, Pope M: Nonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:384–390, 2002Google Scholar

14. Weiss RD, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, et al: Medication compliance among patients with bipolar disorder and substance use disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59:172–174, 1998Google Scholar

15. Frank E, Prien RF, Kupfer DJ, et al: Implications of noncompliance on research in affective disorders. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 21:37–42, 1985Google Scholar

16. Keck PE, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al: Factors associated with pharmacologic noncompliance in patients with mania. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:292–297, 1996Google Scholar

17. Danion JM, Neunruther C, Krieger-Finance F, et al: Compliance with long-term lithium treatment in major affective disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry 20:230–231, 1987Google Scholar

18. Sajatovic M, Blow FC, Ignacio RV, et al: Age-related modifiers of clinical presentation and health service use among veterans with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 55:1014–1021, 2004Google Scholar

19. Patel NC, Crismon ML, Miller AL, et al: Drug adherence: effects of decreased visit frequency on adherence to clozapine therapy. Pharmacotherapy 25:1242–1247, 2005Google Scholar

20. Sanchez RJ, Crismon ML, Barner JC, et al: Assessment of adherence measures with different stimulants among children and adolescents. Pharmacotherapy 25:909–917, 2005Google Scholar

21. Al-Zakwani IS, Barron JJ, Bullano MF, et al: Analysis of healthcare utilization patterns and adherence in patients receiving typical and atypical antipsychotic medications. Current Medical Research and Opinion 19:619–626, 2003Google Scholar

22. Hertz RP, Unger AN, Lustik MB: Adherence with pharmacotherapy for type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study of adults with employer-sponsored health insurance. Clinical Therapeutics 27:1064–1073, 2005Google Scholar

23. Yu YF, Nichol MB, Yu AP, et al: Persistence and adherence of medications for chronic overactive bladder/urinary incontinence in the California Medicaid Program. Value Health 8:495–505, 2005Google Scholar

24. Gianfrancesco FD, Rajagopalan K, Sajatovic M, et al: Treatment adherence among patients with bipolar or manic disorder taking atypical and typical antipsychotics. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:222–232, 2006Google Scholar

25. Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al: Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Medical Care 40:630–639, 2002Google Scholar

26. Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al: Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:692–699, 2004Google Scholar

27. Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK: Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatric Services 52:805–811, 2001Google Scholar

28. Valenstein M, Blow FC, Copeland LA, et al: Poor antipsychotic adherence among patients with schizophrenia: medication and patient factors. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:255–264, 2004Google Scholar

29. Keck PE, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al: Compliance with maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 33:87–91, 1997Google Scholar

30. Jamison KR: Medication compliance, in Manic Depressive Illness. Edited by Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

31. Revicki DA, Hirschfeld RM, Ahearn EP, et al: Effectiveness and medical costs of divalproex versus lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder: results of a naturalistic clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders 86:183–193, 2005Google Scholar

32. Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow FC, et al: Treatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 8:232–241, 2006Google Scholar

33. Sajatovic M, Davies M, Bauer MS, et al: Attitudes regarding the collaborative practice model and treatment adherence among individuals with bipolar disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry 46:272–277, 2005Google Scholar

34. Sajatovic M, Hrouda D, Davies M: Enhancement of treatment adherence among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 55:264–269, 2004Google Scholar

35. Johnson RE, McFarland BH: Lithium use and discontinuation in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:993–1000, 1996Google Scholar

36. Scott J: Predicting medication non-adherence in severe affective disorders. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 12:128–130, 2000Google Scholar

37. Tondo L, Jamison KR, Baldessarini RJ: Effect of lithium maintenance on suicidal behavior in major mood disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 863:339–351, 1997Google Scholar

38. Post RM, Leverich GS, Altshuler L, et al: Lithium-discontinuation-induced refractoriness: preliminary observations. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1727–1729, 1992Google Scholar

39. Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L: Non-response to re-instituted lithium prophylaxis in previously responsive bipolar patients: prevalence and predictors. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1810–1811, 1995Google Scholar

40. Link BG, Streuning EL, Neese-Todd S, et al: Stigma as a barrier to recovery: the consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 52:1621–1626, 2001Google Scholar

41. Wright ER, Gronfein WP, Owens TJ: Deinstitutionalization, social rejection, and the self-esteem of former mental patients. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:68–90, 2000Google Scholar