Measuring Trends in Mental Health Care Disparities, 2000–2004

In the 2001 Surgeon General's report, Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity, eliminating racial disparities in the utilization of mental health services was considered a top priority. These disparities are contributors to the greater likelihood among African Americans and Hispanics than among whites that major depressive disorder will become a chronic illness ( 1 , 2 ) and that major depression leads to a higher degree of functional limitation among African Americans than among the other two groups ( 2 ). In this study we examined whether gains in eliminating mental health care disparities have occurred since the landmark Surgeon General's report.

To examine trends in mental health care disparities, rigorous definitions of disparities should be used. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) in its Unequal Treatment report ( 3 ) defined disparities in quality of care as differences between racial-ethnic minority groups and whites that are attributable to socioeconomic factors (and insurance) but not to health status and treatment preferences. This definition recognizes that health status differences, such as the lower rates of depression found among African Americans and Hispanics than among white Americans ( 1 ), should be adjusted for or balanced across racial-ethnic groups in determining whether lower service use is truly a disparity or only reflective of lower need. On the other hand, disparities accounted for by socioeconomic factors, such as income or insurance, remain an important part of the picture and should be included in the disparity calculation. Poverty status strongly mediates Hispanic-white and African-American-white disparities in mental health specialty care ( 4 , 5 ). Acculturation (measured by English proficiency, nativity, and years in the United States), national origin, and insurance status affect service utilization among African-American and Hispanic subgroups ( 6 , 7 , 8 ) and could mediate racial-ethnic disparities.

Thus implementing the definition of disparities requires the adjustment of variables related to health status. Differences that are attributable to socioeconomic variables should be allowed to enter the disparity calculation. Two previous studies have implemented this definition with a "rank and replace" method that adjusts for health status differences while allowing socioeconomic factors to mediate differences ( 9 , 10 ).

The literature has been inconsistent in its treatment of disparities accounted for by socioeconomic factors; effects of race have been estimated with and without controls for socioeconomic variables ( 4 , 11 ), and unadjusted means and results from models that adjust for socioeconomic variables have been presented ( 12 , 13 ). Identifying the change in the race-ethnicity coefficient between a base model and a more fully specified model is a common method of measuring the mediation of variables ( 14 ). If race effects disappear when socioeconomic differences are controlled for, some investigators deduce that these are not racial-ethnic disparities but rather disparities according to socioeconomic status. A limitation of using this successive-models strategy is that the inference of mediating effects is based on a partially specified model that is likely to be biased. If we accept the notion, based on the IOM definition of disparities, that socioeconomic status should be allowed to mediate differences, then this commonly used method fails to provide an unbiased and quantifiable measure of disparity.

Other published studies have compared unadjusted means between racial-ethnic groups. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), in its National Healthcare Disparities Reports ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ), has used this method to track disparity trends in the probability of receiving any mental health treatment or counseling by using the 2001–2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. These reports found that Hispanics and African Americans had less access than whites to mental health care in each of the years, and the differences persisted after the analyses stratified for income and education. The trend worsened and then appears to have leveled off for African Americans in 2004, whereas the trend for Hispanics worsened over time ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ). Comparing unadjusted means allows socioeconomic factors to appropriately mediate differences, but it does not exclude differences that are attributable to health status in the measurement of disparities. For example, Hispanic Americans are younger than white Americans, and this age difference might mediate differences in utilization between the groups that are not true disparities.

In this study, we improved upon previous methodologies by examining disparities using one regression model that includes both health status and socioeconomic variables and using a new rank-and-replace method that adjusts for health status differences while allowing socioeconomic factors to mediate differences.

Methods

Data

Data used in the analysis are from nationally representative samples of Hispanics, non-Hispanic African Americans, and non-Hispanic whites over the age of 18 taken from five years (2000–2004) of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) ( 19 ). Regression models were fit using MEPS data from time periods pooled from the endpoints (2000–2001 and 2003–2004), allowing us to measure a trend in disparities over time while retaining sufficient sample size (N=67,581) for unbiased estimates.

We estimated trends in two global measures of racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care—having any mental health visits and total mental health care expenditures in the past year. Data were taken from responses to the medical provider and household components of the MEPS. Prices were adjusted to 2004 dollars by using the gross domestic product deflator. Total mental health expenditure was constructed by summing all direct payments during the previous year for mental health-related prescription drugs, inpatient care, outpatient care, office-based care (including counseling and social worker visits), and emergency room use. These expenditures included out-of-pocket payments and payments by private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, and other sources. This measure expands and improves upon the outpatient mental health expenditure variable used in the study by McGuire and colleagues ( 10 ) by including inpatient mental health expenditure and by using actual expenditure from payment data rather than attributing an average price to utilization variables.

The independent variables were grouped into variables that are adjusted for in the IOM definition of health care disparities and those that are not. Mental health status variables were adjusted for in the IOM analysis and include self-reported mental health status (excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor) and the score on the mental health component of the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) ( 20 ). Variables strongly correlated with mental health status (also adjusted for in the IOM method) include the physical health component of the SF-12, gender, age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and 75 years and older), and report on any functional limitation in working at a job, doing housework, or going to school. Education level, income level, region of the country, and insurance coverage were not adjusted for and thus serve as mediating variables.

Applying definitions of disparity

Our main purpose was to apply the IOM definition of disparities, which includes effects mediated through socioeconomic variables. Methods of measuring racial and ethnic disparities can be distinguished by the variables chosen for adjustment and the variables left to mediate the relationship between race-ethnicity and utilization. If whites have higher income than persons in minority groups and income contributes to utilization and access, then racial-ethnic differences resulting from income differences are counted as part of racial-ethnic disparities. Comparisons of unadjusted means contrast racial-ethnic subgroups without adjustment, in effect allowing for mediation by all other variables. Regression-based residual direct-effect methods are the opposite extreme, adjusting for all variables and not allowing for any mediation. IOM methods provide a middle path, adjusting for health status variables while allowing for mediation resulting from socioeconomic variables ( 9 , 10 , 21 ).

In this study we applied the first and third approaches. First, we measured all group averages directly and tested for trends in this total difference. This is the same method used in the AHRQ National Healthcare Disparities Report, which we applied to the 2000–2004 MEPS data. Second, we measured the total difference less the components that were attributable to health status, as recommended by the IOM. The specific question we pose is "How much mental health care would African Americans (or Hispanics) have used if they had the same mental health status as whites but retained their own racial and socioeconomic characteristics?" This counterfactual scenario was assessed in both periods (2000–2001 and 2003–2004). Use by these hypothetical minority subpopulations was compared with actual use by whites in the same period. The difference within time period is the disparity, and the difference in disparity measures the disparity trend. We adjusted for all available mental health status variables and variables that were highly correlated with mental health status, and we allowed differences mediated by socioeconomic status to contribute to disparity calculations. These adjustment methods are described in more detail below, after we describe our empirical model.

Estimation

The IOM definition of disparity calls for model-based predictions. For the dichotomous variable assessing any mental health visit, we used a multivariate logistic regression model. Because we are estimating differences in racial-ethnic differences over two periods (2000–2001 and 2003–2004), main effects of race-ethnicity and year as well as a race-by-year interaction term were used as predictors. Other predictors used were a vector of mental health status and variables highly correlated with mental health status, a vector of socioeconomic variables (education, income, region, and insurance status), and a vector of year indicator variables. To account for racial-ethnic differences in the impact of socioeconomic status and mental health status on mental health care utilization, significant socioeconomic status-by-race interactions and mental health status-by-race interactions were added to the model.

E (Y it =1) = f [ β0 + β1 (year t ) + β2 (race i ) + β3 (year t × race i ) + β4 (MHS i ) + β5 (SES i ) + β6 (MHS i × race i ) + β7 (SES i × race i )]

where f is the inverse logistic function, Y it is whether or not an individual used any mental health care, MHS i is the vector of mental health status and correlated variables, and SES i is the vector of socioeconomic characteristics.

To estimate the continuous medical expenditure variable, we used the same set of covariates from the formula above in a generalized linear model with quasi-likelihoods ( 22 ). The generalized linear model has been recommended as an efficient and reliable estimator of medical expenditure because it is flexible enough to account for the nonlinearity and heteroscedasticity of health care use data ( 23 , 24 ). After assessing the distributional characteristics of the data, we used a generalized linear model with a log transformation of expected expenditures and a distribution of the variance proportional to the mean squared.

Adjustment for mental health status

To implement the IOM definition in the context of racial-ethnic disparities in use of mental health care, the variables related to mental health status should be adjusted while other variables should not. In previous studies that implemented the IOM definition of disparities, health status variables were transformed seriatim, so that the Hispanic and African-American distributions for each health status variable were identical to white distributions ( 9 , 10 ). A rank-and-replace method was used to adjust continuous health status variables: African Americans, Hispanics, and whites were ranked according to their scores on continuous health status variables, and the values of Hispanic and African-American individuals were adjusted to equal the equivalently ranked white individual. For dichotomous health status variables, the authors made adjustments so that African Americans and Hispanics would be similar to whites through random replacement, changing minority health status indicators from 1 to 0 (or 0 to 1) until white and minority proportions were equivalent.

In this study we simplified the adjustment by applying the rank-and-replace method to an index of mental health status rather than to each mental health status variable. This index was created by fitting a model of mental health care utilization and summing the products of the parameter estimates and values of the mental health status variables. This is similar to a model-based prediction except that socioeconomic and race variables, and the constant, are excluded from the prediction. African Americans, Hispanics, and whites were then ranked according to their index scores, and the values of African-American and Hispanic individuals were adjusted to equal the equivalently ranked white individuals, creating a hypothetical minority subgroup that has an index distribution identical to the white subgroup. Next, predicted expenditures for each racial-ethnic group were calculated by summing the mental health status index and the predicted expenditure based on the rest of the variables in the model. This combined linear prediction was then retransformed—either exponentiated to dollar terms or transformed via the logit function to the probability of any mental health visit.

Adjusting in this way does not disturb the nonlinearity of the model because the model is fit before adjustment. Also, adjustment of a composite health status score may be a more plausible hypothetical subgroup than one in which dichotomous variables are switched independently across racial-ethnic groups. That is, the new method equates mental health status distributions by adjusting one index that has a large distribution of values, rather than choosing observations to switch individual indicators for disease from 0 to 1 or from 1 to 0.

Variance estimation

We estimated variances for model coefficients and unadjusted rates that accounted for the complex study design and nonresponse rates of the MEPS, and we standardized stratum and primary sampling unit variables across pooled years ( 25 ). Variance estimates for difference-in-difference comparisons were calculated by using a balanced repeated-replication procedure. This method of measuring standard errors repeats the estimation process used on the full sample on a set of subsamples of the population, each of which is half of the full sample size. Difference-in-difference estimates were calculated for each of the 64 subsamples provided by AHRQ, and the variation of these estimates was calculated ( 26 ). All analyses were conducted with Stata version 9 ( 27 ).

Results

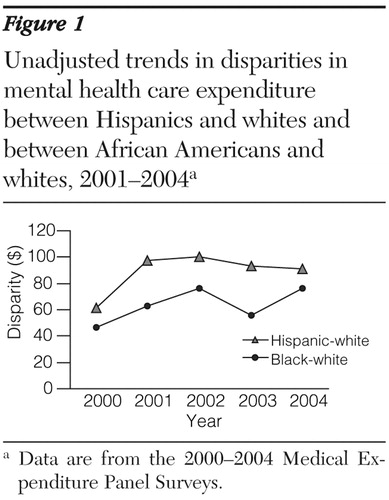

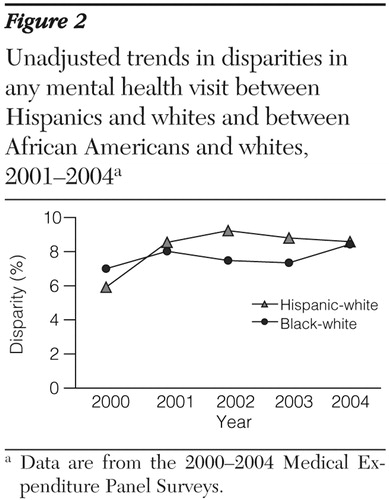

First, we examined the unadjusted differences in mental health expenditure and the probability of having any mental health visit, as shown in Figures 1 and 2 . For Hispanics, disparities appear to have increased sharply between 2000 and 2001 and then to have remained stable but high. African-American-white disparities in access to mental health care appear to have increased slightly over the five-year period.

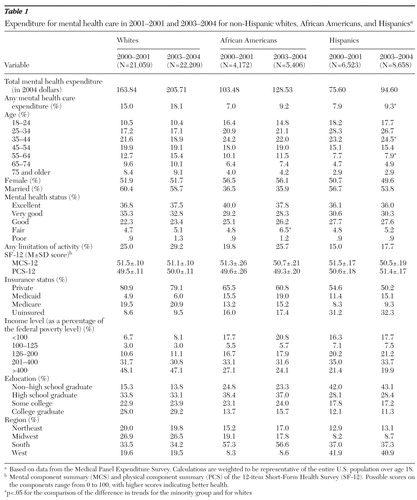

Table 1 shows unadjusted comparisons on pooled data for the first two and last two years in our series. African-American-white and Hispanic-white differences were found within each period in having any mental health visit and total mental health expenditure. African-American-white differences in mental health use and expenditure remained unchanged between 2000–2001 and 2003–2004. Hispanic-white differences in any mental health visit showed an increase that approached significance (p=.07), and Hispanic-white differences in mental health expenditure remained unchanged over the same period. Table 1 also presents descriptive data on the different racial-ethnic groups in each period. Between 2000–2001 and 2003–2004, significantly more Hispanics than whites shifted into the 35- to 44-year age group, and a significant difference in the increase between Hispanics and whites in the 55- to 64-year age group was found.

|

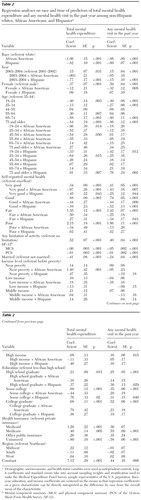

Table 2 presents the coefficients and standard errors for models of total mental health expenditure and any mental health use. These two models were used in our computation of the IOM measure of disparities. Significant interactions between being Hispanic and the 2003–2004 period indicator variable for both utilization variables indicated an increase in Hispanic-white disparities between 2000 and 2004, when all covariates were adjusted for. Other significant predictors of mental health care utilization were being female, being middle-aged, having poorer mental health status, having limitations on activities, scoring lower on the mental and physical components of the SF-12, being more highly educated, being enrolled in Medicaid, and being enrolled in Medicare.

|

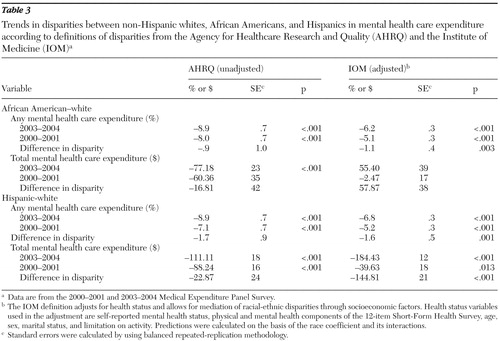

Our main results, based on our new procedures for taking into account health status and allowing appropriate socioeconomic factors to mediate the differences, are displayed in Table 3 . There were significant African-American-white disparities in having any mental health expenditure in both 2000–2001 and 2003–2004. When the IOM definition allowing socioeconomic status-related mediation as part of disparities was used, disparities in 2003–2004 were significantly greater than in 2000–2001; however, this trend was not evident in the unadjusted comparison. No significant African-American-white disparity trends were found in total mental health care expenditure.

|

Within each time period, significant Hispanic-white disparities were found in use of any mental health care within each period using both methods. Across time periods, the trend in disparities worsened between 2000–2001 and 2003–2004 using the IOM definition, but this trend was again missed by the unadjusted comparison. Hispanic-white disparities in total mental health expenditure were also significant within each period when both methods were used. Hispanic-white disparities in total mental health expenditure increased between 2000–2001 and 2003–2004.

Discussion and conclusions

Tracking the use of mental health care by racial and ethnic subgroups is important for monitoring progress in eliminating disparities. In this study we applied measurement techniques based on a rigorous definition of racial-ethnic disparities in health care to identify groups and services where progress lags. Using these methods, we found that the mental health care system continues to provide less mental health care to African Americans and Hispanics than to whites, even after adjusting for mental health status and variables strongly correlated with mental health.

The persistence and worsening of disparities in mental health care among these racial-ethnic groups are similar to the persistence and worsening found in a study of disparity trends in overall medical care (Cook BL, McGuire TG, Zuvekas SH: unpublished manuscript, 2007). One notable difference between the studies is that mental health care disparities in 2003–2004 were greater in percentage terms than medical health care disparities. For example, in 2003–2004 African Americans had a 12% probability of having any mental health expenditure compared with 18% for whites—a percentage disparity of 6/18, or 33%. During the same period, African Americans had a 65% probability of having any medical health expenditure, compared with 79% for whites—a percentage disparity of 14/79, or 17%. Applying the same calculation to Hispanics, we find that they were 38% less likely than whites to have any mental health expenditure, but only 25% less likely than whites to have any medical expenditure. Total mental health expenditure for Hispanics was 58% less than for whites, and total medical health expenditure was 44% less.

Our findings contradict a recent study that called into question whether disparities exist in quality of care, including care for depression ( 28 ). Our research also provides complementary data to a recent community-based epidemiologic study. In that study Alegria and colleagues ( 8 ) found in a large national sample that Hispanics with mental disorders are as likely as white Americans with mental disorders to seek care across a wide range of service providers, including specialty and primary care providers, as well as spiritualists, self-help groups, and chiropractors. Our study suggests that Latinos are less likely than their white counterparts to obtain specialty or primary mental health care. Factors such as insurance or knowledge about the effectiveness of various forms of care may lead Hispanics to seek care in alternative settings rather than specialty and primary care settings where evidence-based care is most likely to be provided.

Like the study by Alegria and colleagues ( 8 ), our study found disparities between whites and Hispanics in health insurance coverage and a strong negative correlation between being uninsured and receipt of mental health treatment. Continued high rates of being uninsured among Hispanics appear to be contributing to the persistence of—and increase in—these disparities.

Recent studies document the positive association between the racial and language concordance of patient and physician and appropriate and timely use of health care ( 29 , 30 ). A continued lack of mental health care providers from minority groups, especially in neighborhoods with high concentrations of minority groups, may also be contributing to the persistence of these disparities.

When the IOM definition of disparities was used, trends were found that are substantially different from those found with other commonly used methods, which demonstrated the strong mediating role played by both the need for mental health care and social factors. Continuing efforts to monitor trends in disparities in mental health care depend on application of a consistent definition of the concept under study. This study offers a replicable methodology for implementing the IOM definition of disparities.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors are grateful for research support from the MacArthur Foundation and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant P50-MD-00537) and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant P50-MH-07469). The authors thank Sam Zuvekas, Ph.D., Margarita Alegria, Ph.D., and Andrea Ault for helpful comments.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, et al: Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine 35:317–327, 2005Google Scholar

2. Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, et al: Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:305–315, 2007Google Scholar

3. Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press, 2003Google Scholar

4. Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services 53:1547–1555, 2002Google Scholar

5. Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L: Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. American Journal of Public Health 93:792–797, 2003Google Scholar

6. Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, et al: Use of mental health services and subjective satisfaction with treatment among Black Caribbean immigrants: results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health 97:60–67, 2007Google Scholar

7. Alegria M, Cao Z, McGuire TG, et al: Health insurance coverage for vulnerable populations: contrasting Asian Americans and Latinos in the United States. Inquiry 43:231–254, 2006Google Scholar

8. Alegria M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, et al: Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health 97:76–83, 2007Google Scholar

9. Cook B: Effect of Medicaid managed care on racial disparities in health care access. Health Services Research 42:124–145, 2007Google Scholar

10. McGuire TG, Alegria M, Cook BL, et al: Implementing the Institute of Medicine definition of disparities: an application to mental health care. Health Services Research 41:1979–2005, 2006Google Scholar

11. Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, et al: Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Medical Care 40:52–59, 2002Google Scholar

12. Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, et al: Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:2027–2032, 2001Google Scholar

13. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

14. Baron RM, Kenny DA: The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51:1173–1182, 1986Google Scholar

15. National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2003. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2003. Available at www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr03/nhdr2003.pdfGoogle Scholar

16. National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2004. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004. www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr04/nhdr2004.pdfGoogle Scholar

17. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2005. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005. www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr05/nhdr05.htmGoogle Scholar

18. National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2006. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2006. Available at www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr06/nhdr06.htmGoogle Scholar

19. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/Google Scholar

20. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S: SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1995Google Scholar

21. Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ: Integrating research on racial and ethnic disparities in health care over place and time. Medical Care 43:303–307, 2005Google Scholar

22. McCullagh P, Nelder JA: Generalized Linear Models. London, Chapman and Hall, 1989Google Scholar

23. Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM: Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. Journal of Health Economics 23:525–542, 2004Google Scholar

24. Manning W, Mullahy J: Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? Journal of Health Economics 20:461–494, 2001Google Scholar

25. MEPS HC-036: 1996–2004 Pooled Estimation File. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Oct 2006. Available at meps.ahrq.org/mepsweb/datastats/downloaddata/pufs/h36/h36u04doc.pdfGoogle Scholar

26. MEPS HC-036BRR: 1996–2004 Replicates for Calculating Variances File. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2006. Available at www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/datastats/downloaddata/pufs/h36brr/h36b04doc.pdfGoogle Scholar

27. Stata Statistical Software 9.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2005Google Scholar

28. Asch SM, Kerr EA, Keesey J, et al: Who is at greatest risk for receiving poor-quality health care? New England Journal of Medicine 354:1147–1156, 2006Google Scholar

29. LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A, Jones KE: The association of doctor-patient race concordance with health services utilization. Journal of Public Health Policy 24:312–323, 2003Google Scholar

30. Lasser KE, Mintzer IL, Lambert A, et al: Missed appointment rates in primary care: the importance of site of care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 16:475–486, 2005Google Scholar