A Comparison of Factors Used by Physicians and Patients in the Selection of Antidepressant Agents

Depression is a prevalent and treatment-responsive illness, yet most people experiencing a major depressive episode go either undetected or inadequately treated ( 1 , 2 ). For those who do receive antidepressant treatment, which is the most commonly used treatment method in family practice, poor adherence to the treatment plan is common and contributes to inadequate responses and relapse of symptoms ( 1 , 3 ). The minimum suggested duration of antidepressant treatment for a major depressive episode is eight months, consisting of an eight- to 12-week acute treatment phase followed by a minimum of six months of maintenance therapy ( 4 ). However, approximately one in ten patients prescribed an antidepressant does not have the initial prescription filled ( 5 ), and among those who do, 30 percent stop taking their medication within a month and 45% to 68% stop treatment altogether by three months ( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). Long-term adherence, of at least eight months, is clearly desirable, given that the greatest benefit of antidepressant treatment appears to be the associated reduction in risk of relapse ( 10 ).

Effective interventions aimed at improving treatment adherence remain elusive despite extensive efforts ( 11 , 12 ). However, as noted by Donovan ( 13 ), the patient's perspective has not been considered adequately, and several studies have demonstrated that physicians' recommendations often do not match patients' treatment preferences ( 14 ). Donovan suggested that involving patients more fully in treatment decisions could lead to improved long-term treatment acceptance. The benefits of this approach, though not necessarily achieved in all investigations, include improved patient knowledge, a sense of feeling informed, satisfaction with the decision-making process, reduced decisional conflict, and adherence with the treatment decision. There is little evidence as yet that supports the contention that including patients in the decision-making process leads to improved clinical outcomes. The benefits of including patients more fully in treatment decisions have been demonstrated for patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and cancer ( 15 , 16 ). No studies have examined the effect of this approach when making antidepressant treatment decisions for patients with depression, although there are indications that patients with depression would prefer and may benefit from a collaborative decision-making approach regarding their treatment options ( 17 , 18 ).

The process of involving patients in treatment decisions requires an exchange of information to ensure that both practitioners and patients are making informed contributions. That is, practitioners will need to learn about the patient's illness, treatment experiences, other health problems, treatment preferences, and payment issues, and patients will need to be informed about the various treatment options and will need to be provided with the opportunity to consider this information before indicating their preferences ( 19 , 20 ). The efficiency of this process can be improved on by knowing in advance what information is important to patients for making treatment decisions. Regarding antidepressant treatment, no studies have identified what factors are most important to patients in choosing a particular agent. This information is essential to facilitating their informed participation in the decision-making process. The purpose of this study was to identify and measure the value of antidepressant treatment selection factors, from the patient's and the practitioner's perspectives, for a patient in primary care with depression for whom the initiation of antidepressant therapy is desired.

Methods

Surveys

Two matching cross-sectional surveys were completed in Nova Scotia, Canada, one with general practitioners and the other with patients of general practitioners. The content of the survey was first developed and used in a pilot study followed by input from two focus groups, one involving general practitioners and the other involving patients with a history of depression ( 21 ). The objective of the focus groups was to further develop the survey used in the pilot project. The content validity of the survey was improved by having the focus group participants identify all possible drug-related factors that can contribute to the selection of an antidepressant for a typical patient who is being treated for depression by a general practitioner and to assess the readability and interpretation of the draft survey.

Upon completing the focus groups, the primary investigator initially classified each antidepressant factor as nondifferentiating, simple and differentiating, or complex and differentiating. Factors that did not require advanced knowledge or training yet distinguished one antidepressant from another were designated as simple and differentiating factors. Examples include common side effects and prescription cost. Factors that differentiate antidepressants from one another but require physician knowledge and judgment, such as interactions between drugs, were classified as complex with differentiating factors. Several factors were identified and included in the survey that do not differentiate one antidepressant from another (for example, treatment duration). These factors were included to determine what general information about antidepressants is important to patients. The original categorical designation of each factor was then reviewed and approved by the other investigators. It was reasoned that informing patients of how antidepressants differ in terms of their simple, differentiating factors could be used to facilitate their direct involvement in the antidepressant selection process, whereas providing information on the complex, differentiating factors would be impractical and would not be desired by most patients ( 22 ). Information regarding the nondifferentiating factors would not support the decision-making process.

The final surveys consisted of two main questions. The first question asked participants to score all factors identified in the focus groups on a 5-point Likert scale. The second question requested that participants rank only the 12 simple, differentiating factors from 1, most important, to 12, least important, to estimate their relative importance in the treatment decision-making process. Patients were asked to respond to the two main survey questions from their own perspective. General practitioners were asked to respond on the basis of what they perceived to be important for patients to make informed decisions.

Participants

In the fall of 2001 patients were recruited to participate in the survey while waiting for appointments with their general practitioners at four family practice sites. Sites included a rural family practice clinic, an urban family practice clinic serving a primarily low- to middle-income population, an urban family practice clinic serving a primarily middle- to upper-income population, and a university health care service. All consecutive patients 18 years or older with appointments (regardless of the reason for their visit) were approached and invited to participate unless directed otherwise by the patient's physician for reasons of literacy, cognition, or uncooperativeness. As such, patients without any mental health problems were eligible to participate. Patients with no history of antidepressant use were included to determine whether decision-making factors were affected by antidepressant experience.

General practitioners' surveys were mailed to a randomly selected sample of 247 of the 950 licensed general practitioners in primary care in Nova Scotia during the same period. Participation enhancements for general practitioners included an introductory letter, up to three reminder notices, and entry into a drawing for one of three Can$150 gift certificates for redemption at a medical bookshop ( 21 , 23 ). There were no participation inducements for patients. This study was approved by the Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Board at Dalhousie University.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of this study was the proportion of respondents agreeing on the first-ranked factor, which was compared between groups using the chi square test ( 24 ). On the basis of the pilot survey, we estimated that 90 percent of patients would consider common side effects to be the most important factor. An absolute difference of ≥15 percent would indicate an important difference in the valuation of this decision-making factor by physicians and patients. To be able to detect this difference ( α =.05, β =.20), 224 participants (112 in each group) were required. A total of 247 surveys were mailed to general practitioners to compensate for the predicted 50% nonresponse rate and 10% nondelivery rate. Patient recruitment of a minimum of 28 patients occurred at four general practitioners' sites of practice.

Rankings of the 12 simple, differentiating factors were compared between groups by calculating and plotting standardized rank scores for each factor as [13-(sum of ranks/N)]× 100/12. The multinomial distribution of ranks of each of these 12 factors was compared between groups using the Wilcoxon ranked-sum test ( 24 ). This test also was used to compare the distribution of Likert scores between groups for the 20 factors listed in the first survey question and to determine the effect of patient experience with antidepressants. The alpha value for these multiple comparisons was adjusted to .01 to reduce the probability of a type I error. Cronbach's alpha was used to evaluate the internal consistency reliability of the questions with Likert scales ( 25 ).

Data management and analysis were completed with SPSS version 10.0.5 statistical software.

Results

Survey response and participants

Of the 181 consecutive patients across four sites, a total of 134 (74%) gave informed consent to participate and 127 (95%) completed the survey. The net general practitioners' survey return rate was 46%. Of the 247 surveys mailed, five were deemed ineligible (respondents were not in active practice) and 110 were returned. Cronbach's alphas were .84 and .81 for responses by patients and general practitioners, respectively, for the 20 factors scored on a 5-point Likert scale.

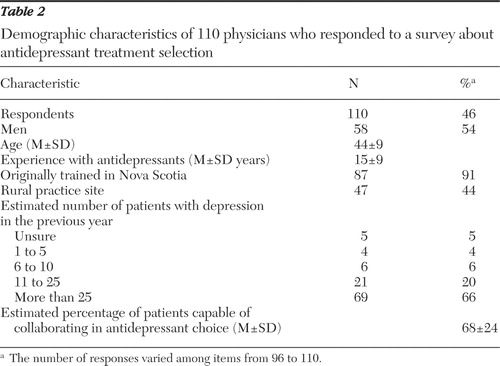

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the characteristics of the survey participants. Across the four sites there were significant variations in patient age, median income category, and history of antidepressant use. Only 19% of patients paid cash for prescription drugs without support from private insurance or government assistance. Most financial support was from private insurance (73%). Experience with antidepressants (44%) was higher than anticipated in this sample.

|

|

Comparison of selection factors

Among the 12 simple, differentiating factors, the most frequently first-ranked factor, the primary endpoint, was common side effects for both the patient group (40 of 116, or 34%) and the general practitioner (49 of 110, or 46%) group. The sum of ranks was used to determine the relative priority for each of the 12 simple, differentiating factors from the primary care patients' perspective, as estimated by patients of general practitioners and by general practitioners ( Table 3 ). Four of the same factors were in both groups' top six factors, suggesting moderate agreement of the factors considered most important for supporting antidepressant-related decisions. The standardized rank scores further illustrate the intermediate matching of values attributed. [See supplemental Figure 1 at ps.psychiatryonline.org for further detail on attributions of importance by patients and practitioners.]

|

In comparison with patients, the general practitioners clearly attributed greater importance to prescription cost. Only 16% of patients ranked this factor in the top three, whereas 59% of general practitioners gave it this priority (p<.001). The 23 patients who were paying 100% for prescriptions ranked cost as fourth in importance. Agreement regarding side effects pertained only to common side effects. The two groups assigned different priorities to uncommon serious side effects. Physicians discriminated between the two categories of side effects, with a difference in the standardized rank scores of 42.9, whereas patients considered uncommon serious side effects only slightly less important than common side effects, with a difference of 15.5, and on par with precautions and physician's experience with the antidepressant. Other factors showing different priorities between groups included dosing schedules and time in use. Both groups agreed that the factors of lowest priority were the need for blood tests, common other uses for the antidepressant, and pill appearance.

Mean patient scores were significantly higher than general practitioners' scores for 11 of 20 factors scored by Likert scale. Only cost was scored significantly lower. [See supplemental Figure 2 at ps.psychiatryonline.org for a rank ordering of the mean patient and physician scores by antidepressant selection factor.] Scoring distributions also tended to be different between patients and general practitioners. Fourteen of 20 factors showed statistically different Likert scoring distributions. When only the simple, differentiating factors were considered, six of 12 ranking distributions differed between patients and general practitioners ( Table 4 ).

|

Fifty-six patients (44%) indicated that they had experience with antidepressants, and 30 of 127 patients (24%) stated they were currently taking an antidepressant. None of the 12 ranking distributions was significantly different between patients with and without antidepressant experience ( Table 4 ). [Supplemental Figure 3 at ps.psychiatryonline.org shows the general agreement in factor ranking between patients with and without antidepressant experience.] Analysis of Likert-scale scores found similar results. The distributions of 14 of 20 factors were significantly different compared with the general practitioners in the group with treatment experience and also in the group without experience. Again, there were no significant differences between patient subgroups (those with or without previous antidepressant experience) in the distributions of the 20 factors.

Discussion

Not all factors identified in the focus groups distinguish one antidepressant from another—for example, the expected duration of treatment or the usual time to onset of subjective benefits. These factors, though important in terms of educating the patient about what to expect from treatment, do not help patients, or practitioners, select among antidepressant agents. Factors that differentiate antidepressants can be divided into two groups, complex and simple. To differentiate among the antidepressants using complex factors—such as those based on interactions between drugs, mechanisms of action, and management of adverse effects—medical training or lengthy details are required. Asking a patient to consider these factors would be impractical. However, by knowing how antidepressants differ in terms of simple, differentiating factors, patients can participate in the antidepressant selection process.

Of the simple, differentiating factors, both patients and general practitioners ranked common side effects as most important. However, when considering the top six ranked factors, the two groups had only intermediate agreement on factor priority. Both groups agreed that common side effects, precautions, physician experience, and problems when discontinuing antidepressant treatment were important factors to consider. However, there was increasing divergence with respect to the importance of dosing schedule, time in use, uncommon serious side effects, and particularly prescription cost.

The most striking difference identified was how prescription cost was valued. Physicians projected cost to be the second most important simple, differentiating factor for a patient to consider in selecting an antidepressant, whereas patients of general practitioners ranked it ninth of 12. Because this finding suggested that this factor is sensitive to prescription payment method, we conducted a subanalysis of patients who paid cash for prescriptions and found cost to be ranked fourth of 12. This finding indicates that practitioners should ask their patients if they have medication insurance (public or private) when choosing an antidepressant. How patients pay for medications in our sample matched well with national statistics (22% paid cash, and 78% had private or public insurance), suggesting that the results may apply elsewhere in Canada ( 26 ).

Possibly the most important difference in priorities was found for uncommon serious side effects. The large separation between the two side effect factors implies that general practitioners feel patients should strongly consider common but not uncommon serious side effects when choosing an antidepressant. Patient responses suggested that knowing the uncommon serious side effects is important in the treatment selection process. Others have similarly found that most patients wish to be informed of all possible treatment-related risks ( 27 ). The difference in priority level between patients and physicians may in part reflect different perceptions of what is meant by uncommon, or it may relate to the challenges of discussing uncommon or rare serious adverse effects in routine practice. These include the time involved, the possibility of inducing irrational decisions, and the not uncommon difficulty of addressing the uncertain causal link ( 28 , 29 ). However, despite these issues, practitioners remain ethically bound to inform patients of the potential risks of treatment, even if rare ( 30 , 31 ). Further work is needed to determine the most effective and constructive ways in which this can be accomplished.

Contrary to what was expected, patient experience with antidepressants did not lead to improved concordance with general practitioners' values. The priorities of patients with and without antidepressant experience were very closely matched. Findings suggest that what was important to patients when receiving their first antidepressant remained important later with growing experience. It also supports the decision to survey an unselected sample of primary care patients.

On the basis of this survey, patients and practitioners, using a shared decision process, should consider how antidepressants compare in terms of risks (common and uncommon side effects, precautions, and discontinuation problems), physician experience (taking care not to unduly influence the decision), prescription cost, and dosing schedule. Providing this information relative to antidepressant choice would satisfy patients' expressed informational needs for differentiating among their treatment options. However, this information alone would not be sufficient for fully informing a patient about antidepressant therapy. Other information identified as important to patients by this survey was treatment effectiveness, the possibility of drug interactions, the time it takes for the benefits of treatment to become noticeable, and how the medication works. These findings are consistent with the observations and recommendations made by Bultman and Svarstad ( 20 ). Inclusion of this information in a general, noncomparative format is critical for informing patients about what to expect from treatment regardless of the medication chosen and may in and of itself contribute to improved treatment acceptance ( 8 , 20 ).

The findings of this research need to be put into context of the overall goal of antidepressant therapy, which is to improve patient outcomes. The overriding assumption is that patient participation in antidepressant decisions will lead to improved acceptance of the antidepressant in the long term. Also, this improvement should, in turn, offer better patient outcomes, such as improved symptom response and quality of life, a greater probability for a timely return to normal functioning, and a reduction in the risk of relapse. However, numerous interventions, such as patient education programs, aiming to improve these outcomes have been tried with disappointing results. What does appear to provide benefit is a collaborative approach that includes enhanced patient education, some form of case management, and application of the shared care model among practitioners ( 32 , 33 ). It is therefore necessary to test this assumption while also applying the other components of care shown to be predictive of these desirable outcomes.

Although the setting of this study was a single province in Canada, it seems reasonable to assume that patient preferences for antidepressant information would be similar overall in other countries. What may vary somewhat is the value attributed to drug cost depending on patient ability to pay as well as the patient's expectation of financial support.

Conclusions

The findings of this survey of patients and general practitioners have identified and prioritized the factors considered necessary for supporting patients' informational needs for making informed shared decisions regarding antidepressant treatment. Overall, there was a moderate difference in informational expectations between physicians and patients. Follow-up interventional studies are required to determine if this level of discordance can be reduced—for example, through increased application of the shared decision-making model ( 19 )—and if a reduction in turn leads to improved treatment outcomes. The findings of this study can be used to guide the choice of information, comparative and general, to be included in an aid for decision making about antidepressant treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was completed as Dr. Gardner's master's thesis in Community Health and Epidemiology at Dalhousie University. Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation. The funding agreement ensured the authors' independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The authors acknowledge the contributions of John Hickey, M.D., Kevin Duplisea, B.Sc.Pharm., Lindsay King, B.Sc.Pharm., Rachelle Couttreau, B.Sc.Pharm., Harold Boudreau, B.Sc.Pharm., Kimi Tiwana, B.Sc.Pharm., and Andrea Murphy, Pharm.D.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 277:333-340, 1997Google Scholar

2. Depression in Primary Care: Treatment of Major Depression. AHCPR pub no 93-051. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

3. Pampallona S, Bollini P, Tibaldi G, et al: Patient adherence in the treatment of depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 180:104-109, 2002Google Scholar

4. Reesal RT, Lam RW, CANMAT Depression Work Group: Clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders: II. principles of management. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 46(suppl 1):21S-28S, 2001Google Scholar

5. Rashid A: Do patients cash their prescriptions? British Medical Journal 284:24-26, 1982Google Scholar

6. Lingam R, Scott J: Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 105:164-172, 2002Google Scholar

7. MacDonald TM, McMahon AD, Reid IC, et al: Antidepressant drug use in primary care: a record linkage study in Tayside, Scotland. British Medical Journal 313:860-861, 1996Google Scholar

8. Maddox JC, Levi M, Thompson C: The compliance with antidepressants in general practice. Journal of Psychopharmacology 8(suppl 1):48-53, 1994Google Scholar

9. Myers ED, Branthwaite A: Out-patient compliance with antidepressant medication. British Journal of Psychiatry 160:83-86, 1992Google Scholar

10. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al: Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 361:653-661, 2003Google Scholar

11. Ley P: Communicating With Patients: Improving Communication, Satisfaction and Compliance. London, Croom Helm, 1988Google Scholar

12. Haynes RB, Montague P, Oliver T, et al: Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Library 2, 2001Google Scholar

13. Donovan JL: Patient decision making: the missing ingredient in compliance research. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 11:443-455, 1995Google Scholar

14. Montgomery AA, Fahey T: How do patients' treatment preferences compare with those of clinicians? Quality in Health Care 10(suppl I):i39-i43, 2001Google Scholar

15. Molenaar S, Sprangers MAG, Postma-Schuit FCE, et al: Feasibility and effects of decision aids. Medical Decision Making 20:112-127, 2000Google Scholar

16. O'Connor A, Rostom A, Fiset V, et al: Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. British Medical Journal 319:731-734, 1999Google Scholar

17. Rokke PD, Tomhave JA, Jocic Z: The role of client choice and target selection in self-management therapy for depression in older adults. Pyschology and Aging 14:155-169, 1999Google Scholar

18. McKinstry B: Do patients wish to be involved in decision making in the consultation? A cross sectional survey with video vignettes. British Medical Journal 321:867-871, 2000Google Scholar

19. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T: Decision making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision making model. Social Science and Medicine 49:651-661, 1999Google Scholar

20. Bultman DC, Svarstad BL: Effects of physician communication style on client medication beliefs and adherence with antidepressant treatment. Patient Education and Counseling 40:173-185, 2000Google Scholar

21. Salant, P, Dillman DA: How to Conduct Your Own Survey. New York, Wiley, 1994Google Scholar

22. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J: What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Archives of Internal Medicine 156:1414-1420, 1996Google Scholar

23. Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al: Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. British Medical Journal 324:1183-1191, 2002Google Scholar

24. Norman R, Streiner D: Biostatistics: The Bare Essentials. Lewiston, NY, Decker, 2000Google Scholar

25. Streiner DL, Norman GR: Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 1989Google Scholar

26. Drug Expenditure in Canada, 1985-2001. Ottawa, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2002Google Scholar

27. Ziegler DK, Mosier MC, Buenaver M, et al: How much information about adverse effects of medication do patients want from physicians? Archives of Internal Medicine 161:706-713, 2001Google Scholar

28. Coulter A: Partnerships with patients: the pros and cons of shared clinical decision-making. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 2:112-121, 1997Google Scholar

29. Fraenkel L, Bogardus S, Concato J, et al: Risk communication in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology 30:443-448, 2003Google Scholar

30. Coulter A: Paternalism or partnership: patients have grown up—and there's no going back. British Medical Journal 319:719-720, 1999Google Scholar

31. Doyal L: Informed consent: moral necessity or illusion? Quality in Health Care 10(suppl. 1):i29-i33, 2001Google Scholar

32. Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, et al: Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: a systematic review. JAMA 289:3145-3151, 2003Google Scholar

33. Whitty P, Gilbody S: NICE, but will they help people with depression? The new National Institute for Clinical Excellence depression guidelines. British Journal of Psychiatry 186:177-178, 2005Google Scholar