A Psychometric Analysis of Project Liberty's Adult Enhanced Services Referral Tool

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center prompted immense concern among mental health professionals about how to meet the needs of individuals who had severe and debilitating reactions to the attacks. Although staff of the New York State Office of Mental Health (NYOMH) embraced the principles of crisis counseling ( 1 ) for the community at large, they advocated for a broader continuum of care that would provide access to evidence-informed treatments for persons who exhibited mental health needs greater than crisis counselors are trained to meet.

In order to meet this need, two interventions that provided enhanced services were developed for adults. The Brief Intervention for Continuing Postdisaster Distress was developed by Jessica Hamblen, Ph.D., and colleagues ( 2 ) at the National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder on the basis of previous research showing the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of trauma-related disorders. This intervention focused on teaching victims to recognize symptoms of postdisaster distress; promoting the use of healthy coping mechanisms to deal with anxiety, depression, or other reactions; and helping victims to make the connection between thoughts and feelings and to replace distorted perceptions with more balanced, accurate views.

The traumatic grief and survivor intervention was created by Katherine Shear, M.D., and colleagues ( 3 ) at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine on the basis of their prior research on the treatment of complicated grief. This intervention determined where victims were in the grieving process and provided them with the opportunity to cope with loss of life in the absence of the person who died. Each of these interventions consisted of ten to 12 sessions. The enhanced services initiative marked the first time that such services were directly offered by a federally funded crisis counseling program.

The enhanced services initiative created a host of challenges for Project Liberty, not the least of which was creating a mechanism for identifying persons who were in need of the more intensive interventions. At the outset, several constraints and principles guided this process. We sought a measure that captured the latent construct of "need for treatment" as manifested in continuing distress and functional disability. The construct "need for treatment" includes the presence of a major psychiatric disorder but is more inclusive to capture intense nonspecific distress of various kinds, including subthreshold disorders and mixed conditions. The measure had to be suitable for use by crisis counselors, and it had to be brief, so as to not use valuable counseling time. Because decisions about referrals had to be made on the spot, it also had to be simple to score and interpret.

Of the available measures, the Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT) ( 4 ) appeared to meet the above specifications most closely. The eight-item SPRINT assesses the core symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (intrusion, avoidance, numbing, and arousal), somatic malaise, stress vulnerability, and impairment in role and social functioning. It has been shown previously to have good reliability and convergent validity with other PTSD diagnostic and psychological functioning measures in both clinical trials and population surveys ( 4 ).

With permission of the authors, we modified the SPRINT for use in crisis counseling to create the SPRINT-E (expanded version). The SPRINT-E was then embedded within Project Liberty's Adult Enhanced Services Tool. The question regarding somatic malaise was replaced by one that assessed health behavior ("In the past month, have your reactions interfered with how well you take care of your physical health? For example, are you eating poorly, not getting enough rest, smoking more, or finding that you have increased your use of alcohol or other substances?"), and three items were added to expand the scope of the measure and to give it a stronger emphasis on functional impairment (not specific to PTSD). One of these questions assesses how "down or depressed" the respondent has been, one assesses how "distressed or bothered" the respondent is by his or her reactions, and one assesses the respondent's perceived ability to overcome problems without further assistance. One final question was added ("Is there any possibility that you might hurt or kill yourself?") but was not included in the score. Rather, it was included in the scale as a precaution and instructs the counselor to refer the respondent for immediate psychiatric intervention. [The SPRINT-E is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

This article presents an analysis of the utility of the SPRINT-E for making and monitoring referrals for enhanced services. The primary purpose of this analysis was to evaluate the internal consistency of the 11 reaction items, determine whether the tool appeared to function comparably for various populations at risk, and draw conclusions about appropriate decision rules for referral to treatment. Whereas scores on the SPRINT-E were related to referral offers by definition, we predicted that scores also would be related to referral acceptance. A relation between SPRINT-E scores and referral acceptance would provide evidence that the SPRINT-E captures respondents' perceived need for professional mental health care.

Methods

Sample

The data were collected from 800 adults in crisis counseling between June and October 2003. The time period began with the introduction of enhanced services and ended approximately two months before Project Liberty came to a close, the last appropriate time to make a referral to enhanced services. Nine people were identified by the referral tool as being at risk for suicide and were referred for immediate psychiatric intervention, and three people did not answer the questions about psychological reactions, leaving a sample of 788 people for the evaluation presented here.

Of these 788 adults, 511 (65 percent) were female and 175 (22 percent) were 55 or older. A majority (462 persons, or 59 percent) received services in Manhattan. Ethnically, 458 (58 percent) were white and non-Hispanic, 181 (23 percent) were Hispanic, and 118 (15 percent) were African American. Thirty-one adults (4 percent) were Asian, Middle Eastern, Native American, or from another racial or ethnic group. Most (646 persons, or 82 percent) fell into one or more specific risk categories related to September 11, 2001 (categories were not mutually exclusive): 142 (18 percent) were family members of the deceased, 100 (13 percent) were rescue and recovery workers, 103 (13 percent) were World Trade Center evacuees, 156 (20 percent) were employed or unemployed workers displaced as a result of the attacks, and 307 (39 percent) were those who had experienced past trauma, mental health, or substance abuse problems.

Measures and procedures

Project Liberty's Adult Enhanced Services Referral Tool assessed basic demographic characteristics, risk categories, and psychological reactions to the events of September 11, 2001. Except for the final question on suicide, all SPRINT-E questions about psychological reactions in the past month were answered on a 5-point scale. Possible scores range from 1, not at all, to 5, very much (scores on the original SPRINT range from 0 to 4). The collaborators set the initial criterion for referral at a threshold that was consistent with their clinical judgment and with estimates of service capacity through this program. Capacity was determined by program administrators on the basis of the number of agencies that were approved to provide enhanced services, the average number of staff trained in the interventions at each site, the number of sessions in the model, and the anticipated duration of each session. Adults who had at least three intense reactions in the past month were offered a referral to enhanced services. Intense reactions were operationalized as a score of 4, quite a bit, or 5, very much.

All crisis counselors attended a full-day training session on the rationale for expanding the services available through Project Liberty, the interventions that were offered as part of enhanced services, administration and scoring of the referral tool, and skill building around techniques for helping service recipients understand and take advantage of their referral options. Crisis counselors were trained to use a structured interview style with the recipient to complete the referral tool. The questions were initially read verbatim, but counselors were allowed to paraphrase or clarify a question if the client was uncertain of his or her response. A manual was used in the training session and was provided to the crisis counselors for future reference.

Overall, 198 participants (25 percent) were screened during their first or second session, 223 (28 percent) were screened during their third session (three sessions was both the median and mode), 176 (22 percent) were screened during their fourth through seventh session, and 191 (24 percent) were screened during their eighth or later session. Counselors were advised to administer the referral tool during the second or third session. Although counselors had some discretion, the general philosophy of Project Liberty was that assessment should not become a routine aspect of an initial visit with a crisis counselor. Many people seek only a single session of crisis counseling to talk briefly about a specific issue in their lives ( 5 ). The persons who were not screened until a fourth or later session had all been in crisis counseling before the enhanced services program was introduced.

Counselors made a total of 55 errors (7 percent) in using these procedures. In most of these cases, participants were offered a referral to enhanced services even though their scores fell below the criterion of three intense reactions (42 persons, or 5 percent). In the remainder, participants who should have been offered a referral were not (13 persons, or 2 percent). Regular crisis counseling services continued to be offered to individuals who were either not offered a referral to enhanced services or declined such a referral when it was offered.

Completed referral tools were submitted to the NYOMH for services monitoring and program evaluation. No individual identifiers were included on the form. Because of the anonymous nature of the data form for recording service provision, administrative review by the NYOMH Institutional Review Board determined that the use of these data for the purposes of this article did not constitute human subjects research.

Results

Descriptive statistics and internal consistency

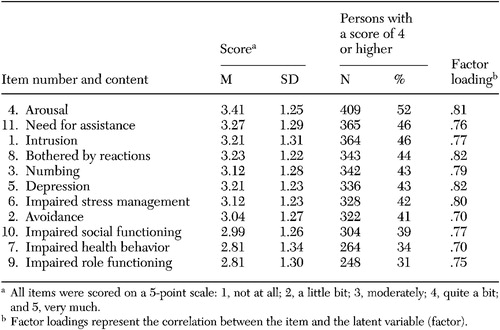

Table 1 provides descriptive detail about the reactions that were measured by the SPRINT-E. On average, each reaction was experienced to a moderate degree (range of 2.8-3.4 for scores). Item number 4 (arousal) was the reaction most likely to be experienced intensely by Project Liberty clients, followed by item number 11 (need for assistance in handling problems). On average, Project Liberty clients endorsed a mean±SD of 4.6±3.5 reactions at an intense level.

|

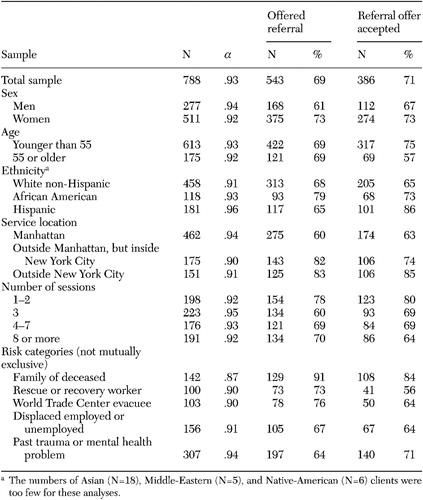

As shown in Table 2 , the internal consistency ( α =.93) of the SPRINT-E was excellent. All 11 items contributed significantly, meaning that if the item was deleted the alpha was lower than .93. Moreover, the scale's reliability was invariant across subgroups in the sample. Consistent with the high alpha coefficient, a principal components analysis demonstrated that the SPRINT-E was unidimensional. Only a single factor emerged in the analysis, and it explained 60 percent of the total variance in the scale. Communalities ranged from .49 to .68, and factor loadings ranged from .70 to .82 ( Table 1 ).

|

Referral offers

Altogether, 514 adults (65 percent) scored at or above the cutoff point of three intense reactions. Including errors, 543 adults (69 percent) were actually offered a referral to enhanced services. In developing the referral tool, considerable discussion had centered on whether to use a value of 3 (moderately) or 4 (quite a bit) as the cutoff point at the item level. If the value used had been 3, an additional 146 people would have met criteria for being referred to enhanced services, resulting in an overall eligibility rate of 84 percent rather than 65 percent.

Table 2 shows the percentages of various subgroups that were offered a referral to enhanced services. The associations of specific demographic, service, and risk characteristics with referral offers and acceptances were tested by a series of single degree-of-freedom chi square tests, with alphas adjusted when necessary for multiple comparisons. Women were more likely than men to receive a referral ( χ2 =13.4, df=1, p<.001). Adults receiving crisis counseling outside of Manhattan were more likely than adults receiving such counseling in Manhattan to receive a referral ( χ2 =48.0, df=1, p<.001), and participants who were screened in their first or second counseling session were more likely than those screened in their third or higher session to receive a referral ( χ2 =10.1, df=1, p<.001). Compared with other participants, family members of deceased victims were more likely to be referred ( χ2 =46.4, df=1, p<.001), whereas persons with past trauma or mental health or substance abuse problems were less likely to be referred ( χ2 =5.2, df=1, p<.05).

Referral acceptance

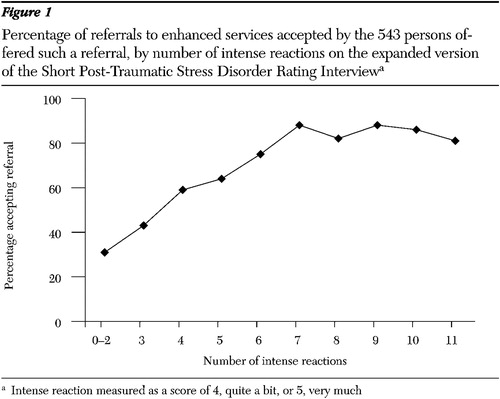

Of the 543 adults who were offered a referral, 386 persons (71 percent of those offered a referral and 49 percent of the total sample) accepted the referral. SPRINT-E scores were strongly associated with referral acceptance. Adults who were offered but declined a referral had a mean of 4.8±2.8 intense reactions, whereas adults who were offered and accepted a referral had a mean of 7.0±2.4 intense reactions (t=9.0, df=541, p<.001). As shown in Figure 1 , the percentage of offers that were accepted by participants increased linearly with the number of intense reactions until this percentage peaked and stabilized at approximately seven intense reactions.

a Intense reaction measured as a score of 4, quite a bit, or 5, very much

Roughly a third of the total sample (283 persons, or 36 percent) had seven or more intense reactions. Of these, 279 (99 percent) were offered a referral (four of the 279 were not offered a referral as a result of error, although they met criteria), and 238 of the 279 (85 percent) accepted the referral. Roughly a third (231 persons, or 29 percent) affirmed three to six intense reactions. Of these, 222 were offered a referral, and 135 of 222 (61 percent) accepted the referral. The difference between these two rates was significant (N=501; χ2 =39.2, df=1, p<.001). Roughly a third of the sample (272 persons, or 35 percent) affirmed less than three intense reactions. Of the apparently random subgroup of participants who were mistakenly offered a referral (42 persons, or 5 percent), 13 accepted (31 percent), a rate significantly lower than that observed for persons who met the chosen criterion of three or more intense reactions (N=543; χ2 =31.7, df=1, p<.001).

Several demographic, service, or risk characteristics were associated with referral acceptance. Of the 534 adults offered a referral to enh anced services, those younger than 55 were more likely to accept a referral than those aged 55 or older ( χ2 =14.2, df=1, p<.001), and participants of Hispanic ethnicity were more likely to accept the referral than participants of other ethnic backgrounds ( χ2 =18.8, df=1, p<.001). Compared with their counterparts, participants were more likely to accept a referral if they received services outside of New York City ( χ2 =16.3, df=1, p<.001) or if they were given the SPRINT-E in their first or second counseling session ( χ2 =8.5, df=1, p<.001). Family members of deceased victims were more likely than others to accept the referral ( χ2 =14.3, df=1, p<.001), whereas rescue workers were less likely than others to accept the referral ( χ2 =8.6, df=1, p<.01).

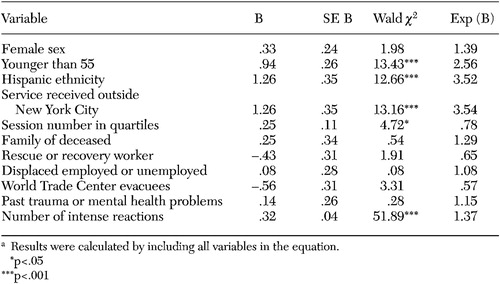

A hierarchical logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine whether the number of intense reactions influenced referral acceptance independent of its correlations with demographic and risk categories. In the first step, variables representing sex (female, 1, and male, 0), age (younger than 55, 1, and 55 or older, 0), ethnicity (Hispanic, 1, and other racial or ethnic groups, 0), service location (outside of New York City, 1, and inside of New York City, 0), and session number in quartiles were entered into the equation. The overall equation was statistically significant ( χ2 =73.5, df=5, p<.001), and each variable significantly and independently predicted referral acceptance. Female sex, younger age, Hispanic ethnicity, service receipt outside of New York City, and fewer sessions each increased the likelihood of referral acceptance.

In the second step, variables were entered into the equation representing membership in specific risk categories (yes, 1, and no, 0): family members of the deceased, rescue or recovery workers, displaced employed or unemployed workers as a result of the attacks, World Trade Center evacuees, and those with past trauma, mental health, or substance abuse problems. These risk categories did not independently influence the probability of referral acceptance.

In the third and final step the number of intense reactions was entered ( Table 3 ). The effect of this variable was quite strong ( χ2 =59.9, df=1, p<.001) and overshadowed all others. Younger age, Hispanic ethnicity, service receipt outside of New York City, and fewer sessions continued to exert an influence on referral acceptance, but the effect of sex dropped out when the number of intense reactions was controlled for.

|

a Results were calculated by including all variables in the equation.

Discussion

New York State's Project Liberty was the first federally funded crisis counseling program to offer, in addition to regular counseling sessions, more intensive, evidence-informed clinical treatments to participants with mental health needs greater than those that crisis counselors are trained to meet. The initiative required a referral mechanism that could be employed systemwide, that could be quickly administered and easily scored by crisis counselors, and that would be consistent with the principles and guidelines of the federal crisis counseling program that funded Project Liberty. Embedded within Project Liberty's Adult Enhanced Services Referral Tool, the SPRINT-E was designed to be a brief measure of current (past month) disaster-related distress, functional impairment, and felt need for professional help, regardless of the presence or absence of specific psychiatric conditions.

These results suggest that the SPRINT-E is an internally consistent measure of postdisaster distress and dysfunction. The alpha of .93 compares favorably to the alpha of .77 to .88 that is reported for its parent measure, the SPRINT ( 4 ). The SPRINT-E was equally reliable for women and men, for older and younger adults, and for African-American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white clients. Its unidimensional structure justifies the use of a scoring algorithm that gives equal weight to all 11 measured reactions.

The number of referral errors (7 percent) may indicate that the scale was not as simple to score as assumed, suggesting that improved training or supervision regarding its use is needed. One possible explanation of the error rate for adults stems from the different rules used for referring children and adults to enhanced services. (Project Liberty also offered evidence-based trauma services tailored for youths; those data were not included here.) Any child, regardless of score on the child tool, could be referred at the counselor's discretion. Possibly, the different rules created some confusion for the adult program. Alternatively, the "errors" could have been intentional, reflecting the counselors' clinical judgment that the individuals should be referred.

A number of demographic, service, and risk characteristics (not mutually exclusive) were related to the likelihood of a participant's scoring at or above three intense reactions on the scale (the determined criterion for referral). Women, persons who were screened outside of Manhattan, those in their first or second counseling session, and family members of deceased victims were more likely than others to receive a referral. Persons with past trauma or with mental health or substance abuse problems were less likely than others to meet the criterion for referral. The SPRINT-E aimed to assess disaster-specific reactions rather than general morbidity, and most of the people who lacked this specific risk factor were more severely exposed to the terrorist attacks themselves.

That the number of intense reactions was, by far, the strongest predictor of referral acceptance among those meeting the criterion for referral suggests that the SPRINT-E does identify persons with a perceived need for professional treatment. It is of note for program policy that the results from a brief psychological assessment provided a stronger basis for referral than membership in a risk category alone. The tool's successful integration into the crisis counseling program is consistent with a small but important body of literature demonstrating that systematic methodologies, such as the use of scales and structured interviews, do not interfere with clinical work and may even improve outcome ( 6 , 7 , 8 ).

Severity of psychological reactions was not the sole predictor of referral acceptance. When the severity of reactions was controlled for, younger age, Hispanic ethnicity, and receipt of services outside of New York City all increased the likelihood that the offer would be accepted. Of these results, the most noteworthy was the influence of the number of previous Project Liberty crisis counseling sessions. When the number of prior sessions was high, clients were less likely to accept the referral than when this number was low. It is possible that some clients who had met with their present crisis counselor a number of times hesitated to establish a new therapeutic relationship. Alternatively, clients may have become discouraged after multiple sessions did not significantly relieve their distress, highlighting the importance of early detection of serious and treatable clinical syndromes.

The SPRINT-E differs conceptually from screening measures for which a cutoff point seeks to identify a high probability of the presence of a distinct clinical syndrome. For continuous latent constructs, there is not a single valid cutoff point, and decision rules (sensitivity and specificity) must be based on judgments of program purpose, capacity, and the consequences of false positives and false negatives in the individual context. The decision rule was set at a level of three intense reactions on the basis of Project Liberty's assumptions regarding the abilities of crisis counselors to help clients with reactions of moderate intensity or less (acceptable) and the overall capacity of the enhanced services program (limited but not scarce). It is important to keep in mind that no one was denied a service. Persons who were not referred to enhanced services continued to receive services as usual.

Our finding that more than 70 percent of those who were offered a referral accepted it could be taken as evidence of the appropriateness of the decision rule established by Project Liberty. However, raising the cutoff point for referral would possibly increase efficiency and might be used where capacity to provide more intensive treatment is more limited. A score of seven intense reactions marked the upper third of the distribution of scores for the total sample, was the mean among clients accepting a referral, and was also the point at which rates of acceptance peaked and stabilized. A criterion of seven intense reactions would have yielded a total samplewide referral rate of 30 percent (238 of 788 persons) and would have ensured that only the most distressed individuals were referred for enhanced services. The use of a cutoff criterion of three intense reactions yielded a total samplewide referral rate of 50 percent (386 of 788 persons) and might be used when community capacity to provide specialized treatment is relatively high. These parameters could be used to guide the choices of future programs in accord with program volume and the number of persons who can be served by more costly clinical treatments. Scores should, of course, be used in combination with other important clinical considerations, such as client preference and other factors that suggest need for more expert intervention.

Some cautions in interpreting and generalizing these findings should be noted. These data describe people who were willing to participate in crisis counseling services. Levels of distress and referral acceptance rates would presumably be lower in non-treatment-seeking populations. The data were collected nearly two years after the World Trade Center disaster, and thus it is possible that highly distressed adults who entered counseling at this point were especially likely to believe that they would not get better without formal help. Finally, rates of actual enrollment in enhanced services are not available for analysis, because of the anonymous nature of the referral data and because no individually identified data were collected for persons who enrolled in enhanced services.

A few words should be said about the study's capacity to illustrate the potential rewards of collaborations between academic researchers and the public sector. Project Liberty was able to augment its capacity by accessing the expertise of academic researchers in developing interventions, referral tools, and manuals for service delivery. Academic knowledge of best practice was coupled with the experience Project Liberty management had gained, and the enhanced services component was implemented as quickly as possible.

Conclusions

In summary, the SPRINT-E provided an apparently successful, empirical basis for referral from counseling to professional treatment. Altogether, the concept of enhanced services, as well as the development of an objective method for identifying adults most in need of these services, heralds a maturation of the field of disaster mental health that is particularly appropriate in the aftermath of terrorism.

Acknowledgments

This evaluation was funded by grant FEMA-1391-DR-NY (titled "Project Liberty: Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program") to New York State from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration administered the grant. The study was also funded by grant K02-MH-63909 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Norris.

1. Flynn B: Mental health services in large scale disasters: an overview of the Crisis Counseling Program. NCPTSD Clinical Quarterly 4:1-4, 1994Google Scholar

2. Hamblen J, Gibson L, Mueser K, et al: Applying research on cognitive behavioral therapy to interventions for prolonged postdisaster distress. Journal of Clinical Psychology 62:1043-1052, 2006Google Scholar

3. Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, et al: Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293:2658-2660, 2005Google Scholar

4. Connor K, Davidson J: SPRINT: a brief global assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 16:279-284, 2001Google Scholar

5. Donahue SA, Covell NH, Foster MJ: Demographic characteristics of individuals who received Project Liberty crisis counseling services. Psychiatric Services 57:1261-1267, 2006Google Scholar

6. Ben-Arie O, Koch A, Welman M, et al: The effect of research on readmission to a psychiatric hospital. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:37-39, 1990Google Scholar

7. Kocsis J, Frances A, Kalma T, et al: The effect of psychobiological research on treatment outcome: a controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:511-515, 1981Google Scholar

8. Marshall R, Spitzer R, Vaughan S, et al: Assessing the impact of research: the experience of being a research subject. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:319-321, 2001Google Scholar