Impact of a Media Campaign for Disaster Mental Health Counseling in Post-September 11 New York

The attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, resulted in loss of life, disruption of daily routine, and increases in the prevalence of mental disorders ( 1 ). After the attacks, the New York State Office of Mental Health (NYOMH) and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) alerted the public to the availability of counseling and referral services through LifeNet, a preexisting toll-free, 24-hour mental health hotline that offered multilingual services. These media announcements began within 24 hours of the attacks ( 2 ). This initial response was followed by the establishment of Project Liberty, a federally funded program that provided free, anonymous crisis counseling and public education services to people affected by the attacks.

Project Liberty was designed to deliver effective, community-based crisis counseling services in the five boroughs of New York City and in ten surrounding counties. Funded by two grants totaling slightly over $155 million by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Project Liberty was administered by NYOMH. In conjunction with local mental health departments, NYOMH mobilized a network of providers to deliver crisis counseling services to the affected populations on an ongoing basis and to initiate a campaign to raise awareness of the availability of free counseling, public education, and referral services.

Because mental illnesses are stigmatized in American society and because people generally do not anticipate needing mental health care in the event of a disaster, people are frequently uninformed about available mental health services. Given the stigma associated with mental illness, and by extension mental health services, people may refuse to seek help. Thus NYOMH viewed conducting a media outreach campaign as a critical element for informing disaster victims of the availability of crisis counseling services provided through Project Liberty and encouraging their use. Also, NYOMH considered "branding" such services as appropriate and potentially helpful for all people affected by the disaster, regardless of their pre-September 11 mental health status. The advertising focused on informing people about the availability of services and how LifeNet could help direct them to services that were convenient and culturally and linguistically appropriate given their disaster-related clinical and personal circumstances. With the goal of reaching the greatest number of people, NYOMH devised a multimedia public outreach strategy to prompt people to learn more about how Project Liberty could meet their disaster-related mental health needs.

NYOMH and DOHMH coordinated city-level and state-level media campaigns. The city campaign focused on reaching people through the dissemination of messages in the subway system, on buses, and in print, and the state campaign supplemented the city campaign by focusing on radio and television advertising, including celebrity endorsements ( 3 , 4 ). For the latter strategy, NYOMH partnered with the Sloan Group, a New York City media firm, to develop and produce the radio and television advertisements. The Sloan Group was responsible for getting the advertisements on the air. Initially, NYOMH relied on public service announcements (the traditional vehicle used in past FEMA-funded crisis counseling programs), but statistics on airplay showed that television and radio stations were airing the ads only outside of peak viewing or listening hours (such as at 3 a.m.). Thus NYOMH decided to begin purchasing prime-time advertising slots from the major New York City broadcast media.

Underlying this strategy was the understanding that an effective media campaign requires broad dissemination of a large number of well-placed, influential media messages ( 5 ). However, this was an expensive proposition in the lucrative New York City media market. Therefore, to assess the impact of this strategy, NYOMH partnered with the New York Academy of Medicine to include questions about Project Liberty in their ongoing epidemiological surveys of the mental health impact of September 11 on New Yorkers. NYOMH's media spending decisions were subsequently guided by three data sources: Sloan Group data on airtime and the number of estimated viewers for the television spots and listeners for the radio spots, New York Academy of Medicine data on how many people reported they had heard about Project Liberty and through what media method they had gained that knowledge, and LifeNet data on changes in call volume over time. This last data source is the focus of the analyses reported in this article.

The DOHMH and NYOMH media campaigns were activated in three somewhat overlapping phases: three months after the attacks on the World Trade Center, the summer of 2002, and around the one-year anniversary of the attacks. NYOMH launched television and radio campaigns promoting awareness of Project Liberty through LifeNet telephone referral services. LifeNet is a community service of the Mental Health Association of New York City, Inc., and offers telephone help and referral to social service and psychology professionals in the greater New York metropolitan area 24 hours a day, seven days a week. After the World Trade Center disaster, LifeNet became the first line of contact for Project Liberty, which was specified in most of the advertising spots. LifeNet primarily assisted in setting up initial referrals, although additional referrals were occasionally given to repeat callers.

The first phase of the city media campaign (mid-November 2001 through April 2002) involved outdoor, print, and radio advertising and distribution of materials ( 3 ). In November 2001, DOHMH launched in English and Spanish the "New York Needs Us Strong" campaign on subways, telephone kiosks, and bus shelters. At the six-month anniversary, 1.4 million "New York Needs Us Strong" booklets in English, Spanish, and Chinese were distributed in major newspapers and delivered to many community organizations. These booklets provided important content regarding reactions to disaster and strategies for coping. In addition, a four-month radio campaign in English, Spanish, and Chinese was conducted on seven leading New York City radio stations having a combined audience of over five million listeners ( 6 ). Radio advertising was augmented by coping information provided for three months on the New York Times Web site, which was estimated to reach more than two million viewers. Throughout this phase, postcards, coffee cups, and wall posters featuring the Project Liberty logo, the LifeNet hotline number, and the campaign slogan were distributed in restaurants, bars, bookstores, and other social venues.

The second phase of the media campaign took place between May and August of 2002. A joint sponsorship with the New York Yankees and New York Mets baseball teams was designed to reach men, including rescue workers and those in the uniformed services. This campaign included messages promoting LifeNet, radio and television announcements, print program advertisements, outdoor signs in ballparks, and specialty promotional items. The program was estimated to have made more than 12 million impressions (the number of viewers seeing the promotions). In addition, television spots targeting different audiences were developed and aired. These included ads that focused on parents with young children and the signs and symptoms of traumatic stress in young children, older adults, and teenagers and young adults. During this phase, newspaper and outdoor media advertisements for Project Liberty services increased. Billboards with the slogan "New York Is Getting Stronger Every Day" were mounted throughout the city, providing 36.3 million impressions in a 90-day period ( 6 ).

The third phase used outdoor and material media, online Web advertising, and publication distribution targeting those who may have experienced delayed reactions to the disaster ( 6 ). Beginning in August 2002, NYOMH launched the "Honor the Past, Embrace the Future" campaign, which prepared for the upcoming anniversary of September 11. The outdoor campaign consisted of advertisements in subways, telephone kiosks, and bus shelters. The print campaign included distributing the Coping After September 11 brochure to target groups and posting Project Liberty advertisements in various newspapers.

In this report, we examine calls to LifeNet as an indication of the impact of Project Liberty's multimedia outreach efforts in notifying the public about ways to access counseling services. Associating the spending on media outreach with one key response to the outreach is a step in assessing the effectiveness of spending. Specifically, this article focuses on the nature, timing, and association between media activities (and media spending) and changes in the volume of calls to LifeNet.

Methods

We obtained data on Project Liberty media activity and on hotline activity from LifeNet. Media advertisement spending and service information originated from two sources, the Sloan Group, which served as the NYOMH media consultant, and invoices paid by the Project Liberty budget office. Sloan Group data included dates of television spots, radio spots, and print advertisements; total expenditure on each media type per week; and the estimated number of people who saw any given advertisement, which was based on impressions estimates (based on Nielsen data). Invoice data included dates of and weekly expenditures for television, radio, newspaper, magazine, and other advertisements (for example, subway placards and brochures) for both New York City and surrounding disaster-declared counties. Invoice data did not include information on the estimated number of people who viewed or listened to a specific advertisement. We received data files describing nine specific periods during the three phases of the media campaign by media type. The length of these periods ranged from under one month to approximately four months.

LifeNet data included 30 variables describing characteristics of telephone contacts (number and type of calls and callers' age, gender, mental health problems, and preferred language), broken down by month and county from November 2000 to December 2002. The data set provided information on call volume for the ten months before September 2001 as well as for the period after the attacks.

We used LifeNet reports of the number of callers requesting Project Liberty services and the number referred to such services to estimate response to media activity. We used these referral numbers as our proxy for the number of World Trade Center disaster-related calls. We recognize that calls to LifeNet are but one possible help-seeking response generated by Project Liberty media outreach; hence, the number of LifeNet callers referred to Project Liberty represents a conservative estimate of the impact of the media campaign.

Results

Media activity

From September 2001 to December 2002, NYOMH spent $9.38 million on Project Liberty media campaigns. Spending varied by media type, with $3,427,000 devoted to "other" advertisements, $2,365,987 to television advertisements, $2,004,546 to radio advertisements, and $1,582,906 to print advertisements. During that period, total television impressions were approximately 549 million. Unfortunately, there were no comparable impressions data for radio, print, and other media.

Trends in media expenditures per month

We found large swings in total media expenditures between September 2001 and December 2002. Total media expenditures peaked at three points: December 2001, March 2002, and September 2002 ( Figure 1 ). During the second phase of the campaign, total expenditures rose more steadily than during the first phase. At the one-year anniversary, total media expenditures spiked dramatically.

a Arrow represents the start of the city media campaign.

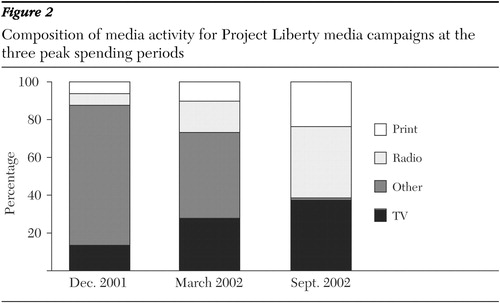

Although the total expenditure trend somewhat matched the three-phase media campaign schedule, each media type followed a different expenditure pattern. Figure 2 shows the changing composition of media activity for the three peak spending periods.

Initially, flyers and billboards were the focus of the campaign, with roughly 74 percent of spending falling into the "other" media category. Television accounted for 14 percent, 28 percent, and 37 percent of spending across the first, second, and third time periods, respectively. Radio advertising increased from 6 percent to 17 percent to 38 percent. At the one-year anniversary, television and radio constituted the largest spending categories, print accounted for 24 percent, and "other" expenses had fallen to 1 percent.

Trends in LifeNet call volume per month

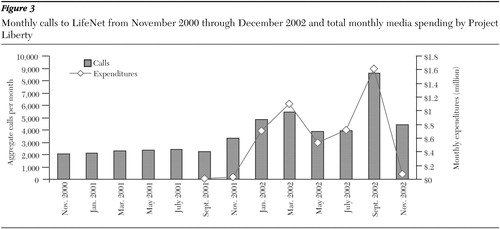

Figure 3 reports monthly calls to LifeNet for the period November 2000 to December 2002. Figure 3 also overlays the trends in total media spending by Project Liberty to describe associations between media spending and LifeNet calls. Compared with data from the previous year, calls to LifeNet after September 11, 2001, increased substantially but unevenly. After a sharp rise from 2,094 to 3,455 calls from September to October 2001, other peaks occurred in January, March, and, especially, September 2002. Given that the Project Liberty media campaigns were mounted in three separate phases, we expected that LifeNet call volumes would peak during specific months and that Project Liberty-related LifeNet calls also would peak during the same months as aggregate LifeNet calls.

Discussion

The descriptions offered above suggest that media spending may have generated help-seeking behavior as measured by calls to LifeNet. This observation is consistent with results from the New York Academy of Medicine surveys after the first phase and one-year anniversary of the attacks. These two surveys indicated that 25 and 50 percent of New Yorkers, respectively, reported knowing about Project Liberty. Of the 50 percent, 30 percent reported that they had considered contacting or had contacted Project Liberty through LifeNet ( 7 ; personal communication, Galea S, 2003).

A second observation is related to the changing composition of media outreach in the Project Liberty outreach efforts. Over time there was increasing reliance on electronic and print media and decreasing reliance on billboards, flyers, and other forms of advertising. This shift, particularly NYOMH's decision to escalate expenditures for television advertising, was driven in large part by results from the New York Academy of Medicine's survey conducted between January and February 2002, which indicated that 60 percent of those who reported knowing about Project Liberty learned of the program through television ads (radio was the third most frequently cited source, at 19 percent). We observed increases in call volumes associated with the shifting composition of media outreach that appear to be independent of the level of media spending. This observation may reflect positive results from NYOMH's use of the survey data to fine-tune the media mix and focus more on television spots, which from the data appeared to reach more people than other media methods. However, this finding merits more focused and detailed analysis of data from Project Liberty and other such outreach efforts.

Conclusions

Catastrophic events appear to generate higher levels of mental distress and need for mental health services. Stigma and lack of information stand in the way of people who seek help for disaster-related distress. Our results suggest the likelihood of a payoff stemming from adopting an outreach strategy that extends well beyond use of public service announcements. The findings reported here suggest that advertising through electronic media, especially television, may be particularly effective in encouraging help-seeking behavior ( 8 ). This latter proposition requires more consideration before being used as the basis for redesigning outreach campaigns. Access to multiple data sources at multiple time points throughout the disaster response effort, including not just call volume or service use but also survey data documenting overall penetration of media-based messaging in the affected population and updated information about disaster mental health services, may be necessary to estimate the impact of multimedia-based campaigns with sufficient precision to justify media spending decisions.

Acknowledgments

This evaluation was funded by grant FEMA-1391-DR-NY (titled "Project Liberty: Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program") to New York State from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration administered the grant.

1. Galea S, Boscarino J, Resnick H, et al: Mental health in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks: results from two population surveys, in Mental Health US, 2002. DHHS pub SMA-3938. Edited by Manderscheid R, Henderson M. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004. Available at www.samhsa.govGoogle Scholar

2. Rosner D, Markowitz D: September 11 and the Shifting Priorities of Public and Population Health in New York. New York, Milbank Memorial Fund, 2003Google Scholar

3. Immediate Services FEMA-1391-DR-NY Final Report. Albany, New York State Office of Mental Health, 2002Google Scholar

4. Felton CJ: Lessons learned since September 11th, 2001, concerning the mental health impact of terrorism, appropriate response strategies and future preparedness. Psychiatry 67:147-152, 2004Google Scholar

5. Atkin C: Media intervention impact: evidence and promising strategies, in Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility. Edited by Bonnie RJ, O'Connell ME. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press, 2004Google Scholar

6. Foster J: Project Liberty Media and Marketing Report: 6/15/02-9/14/02. Albany, New York Office of Mental Health, Dec 6, 2002Google Scholar

7. Rudenstine S, Galea S, Ahern J, et al: Awareness and perceptions of a community mental health program in New York City after September 11. Psychiatric Services 54:1404-1406, 2003Google Scholar

8. Rosenthal MB, Berndt ER, Donohue JM, et al: Demand effects of recent changes in prescription drug promotion, in Frontiers of Health Policy Research. Edited by Cutler D, Garber A. Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press, 2003Google Scholar