The Road Back: Predictors of Regaining Preattack Functioning Among Project Liberty Clients

The September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center resulted in a large-scale mental health intervention program, Project Liberty, which was developed to help individuals affected by the attacks return to their preattack level of functioning. The New York Office of Mental Health (NYOMH) received funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to provide widespread educational and crisis counseling services to residents of the greater New York City metropolitan area by a large network of trained mental health professionals and paraprofessionals ( 1 ).

The assumption underlying the FEMA crisis counseling model is that most people's stress reactions, although personally disturbing, are normal responses to a traumatic event and will be short term. When brief crisis counseling was insufficient to return the person to a predisaster level of functioning, a referral was offered to professional mental health services ( 2 ) or to Project Liberty enhanced services ( 3 ) after the enhanced services component was implemented. Although ongoing case management was not a component of the Project Liberty program, persons in need of other services, such as financial assistance, employment, or housing, were referred to disaster response agencies, such as the Red Cross, or other social service agencies for help.

Initial evaluations of the mental health impact of the attacks involved estimating anticipated service needs of various exposure groups ( 4 ) and assessing the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and other symptomatology among affected residents of New York City ( 5 , 6 ) and nationwide ( 6 , 7 ). These surveys indicated the existence of probable attack-related PTSD in 7 to 11 percent of residents within the greater New York metropolitan area ( 5 , 6 , 8 ) and about 10 percent of public schoolchildren in New York City ( 9 ). The surveys also indicated substantial stress symptoms in 44 percent of a national sample ( 7 ).

Within a year after the attacks, however, the prevalence of trauma symptoms had decreased substantially ( 10 ) and anticipated increases in disaster-related mental health visits had not materialized ( 11 , 12 ). Moreover, despite this return to normalcy among much of the general population, a substantial number of New York City residents reported experiencing serious symptomatology for up to a year after the attacks ( 11 , 13 ). Among these individuals, ongoing PTSD and depression were associated with having greater exposure to risk during the World Trade Center attacks, having experienced prior trauma, being single, and having low levels of social support ( 11 ) as well as having experienced loss of job, residence, or family members or friends in the attacks ( 13 ). Greater risk exposure, more lifetime trauma, and reported depression and PTSD were associated with more frequent mental health visits related to the World Trade Center disaster for a year after the attacks ( 11 ).

Community surveys provided valuable information about mental health needs and recovery in the New York City region for up to a year after the attacks. However, they provided little detail regarding what helped or predicted return to normalcy. This investigation focused on whether Project Liberty service recipients who reported satisfactory life functioning before the World Trade Center attacks were likely to return to similar levels of functioning after the attacks. The study also determined whether respondents who did not return to similar preattack levels of functioning reported functioning as being at least better than "poor" at the time of the assessment. We also examined demographic characteristics and risk factors related to the attacks that predicted this return to satisfactory functioning after the attacks.

Methods

Participants

Data were examined for persons who received crisis counseling from Project Liberty. Data were gathered from 463 respondents to brief, written, anonymous questionnaires (questionnaire data were collected in two waves, from January to April 2003 and from July to November 2003) and from 153 confidential structured telephone interviews (interviews were conducted from February to June 2003). For both samples, we instructed Project Liberty counselors at participating sites to offer all individuals 18 years or older who received Project Liberty individual counseling services and spoke either English or Spanish the opportunity to participate in this survey to evaluate Project Liberty services. Of the 214 Project Liberty service recipients who agreed to be contacted for the telephone interview, 153 (71 percent) completed the telephone interview; the remaining 61 (29 percent) did not participate for a variety of reasons. The Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the NYOMH institutional review boards each reviewed and approved the research protocol for this investigation.

Measures

Participants were queried about their experiences during the attacks, demographic characteristics, extent of functional impairment, and coping strategies. We structured questions to reflect content that had been used in prior surveys ( 5 , 10 ) and worded these questions to meet a sixth-grade reading level. Respondents also provided retrospective ratings of their functioning during the month before the World Trade Center attacks and during the month immediately before the assessment in five domains: functioning in job or school, maintaining relationships with family and friends, handling daily household activities (for example, cooking and cleaning), taking care of physical health (for example, eating right and getting enough sleep), and staying involved in community activities (for example, sports, church, and volunteer work). Respondents rated their functioning with 4-point Likert scales. Possible scores were 1, poor; 2, fair; 3, good; and 4, excellent.

To examine factors predicting return to preattack levels of functioning after the attacks, for each of the five domains we constructed dichotomous variables that were coded by using two different criteria. The first criterion used was based on whether the respondent rated his or her functioning in the most recent month as being the same or better than the month before the attacks or as being worse. For example, we coded respondents who reported good functioning before the attacks and excellent or good functioning in the most recent month as 1 and coded respondents who reported excellent functioning before the attacks but only good, fair, or poor functioning in the most recent month as 0. Additionally, a second criterion was applied on the basis of whether the respondent reported poor versus fair functioning, good functioning, or excellent functioning in the most recent month; this more restrictive criterion allowed us to identify individuals who were able to return to at least a fair level of preattack functioning.

We used two predictor sets in the models. First, demographic variables included age, gender, race or ethnicity, language preference (English or other language), and location of Project Liberty service sites (inside or outside of New York City). Second, risk variables included four dichotomous measures: whether respondents reported feeling as though they were in immediate danger during the World Trade Center attacks, losing a family member or friend during the attacks, losing their job because of the attacks, and being involved in rescue or recovery efforts.

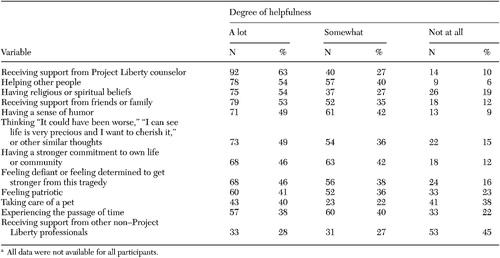

The respondents who were interviewed by telephone were asked to rate whether the following items helped them through the disaster: experiencing the passage of time since the World Trade Center attacks, receiving support from a Project Liberty counselor, receiving support from friends or family, receiving support from non-Project Liberty professionals, having religious or spiritual beliefs, feeling patriotic, helping other people, taking care of a pet, having a stronger commitment to one's own life or the community, having a sense of humor, feeling defiant or feeling determined to get stronger from this tragedy, and thinking something like "It could have been worse," "I can see life is very precious, and I want to cherish it," or other similar thoughts. Items were rated with 3-point Likert scales. Possible scores were 1, not at all; 2, somewhat; and 3, a lot. Data on these items were examined for all 153 respondents who were interviewed by telephone.

Sample selection

For the items that predicted return to a preattack level of functioning, to avoid analyzing duplicate data, we excluded 61 respondents from the telephone interview sample who reported that they also had completed the brief questionnaire. Of the 555 remaining respondents, we excluded 103 who were missing either demographic data or information about their exposure to the terrorist attacks, for a final sample of 452. Within each of the five functional domains, we excluded individuals who did not report functioning or who reported only poor or fair functioning before the World Trade Center attacks. Although excluded from these analyses, they still received Project Liberty services and were likely offered a referral for professional mental health services if appropriate ( 2 ). For each domain the following numbers of participants did not report functioning: job or school, 39 persons (9 percent); family or friends, 13 (3 percent); daily activities, 19 (4 percent); physical health, 12 (3 percent); and community activities, 40 (9 percent). For each domain the following numbers of participants reported poor functioning: job or school, 14 persons (3 percent); family or friends, 18 (4 percent); daily activities, 14 (3 percent); physical health, 17 (4 percent); community activities, 34 (8 percent). For each domain the following numbers of participants reported fair functioning: job or school, 56 persons (12 percent); family or friends, 58 (13 percent); daily activities, 42 (9 percent); physical health, 66 (15 percent); and community activities, 61 (13 percent).

Statistical methods

We applied descriptive statistics to examine whether Project Liberty helped respondents return to preattack levels of functioning and whether factors asked about in the telephone interview were useful in helping respondents cope with the attacks. We used logistic regression models to estimate predictors of return to satisfactory preattack functioning (based on both criteria), entering demographic features first and risk exposure second; for predictors of return to preattack levels of functioning in terms of job or school, we removed the loss-of-job variable. We used likelihood ratio tests to examine the statistical significance of the regression models at each step and chose the highest-level model that demonstrated statistical significance over previous models.

Results

Respondent characteristics

The 452 respondents in the final sample had a mean±SD age of 45.1±13.6 years. A total of 267 (59 percent) were women; 285 (63 percent) were Caucasian, 65 (14 percent) were African American, and 102 (23 percent) were "other" or mixed race; 79 (17 percent) reported that they were Hispanic. A majority (360 respondents, or 80 percent) reported that English was their primary language. A total of 330 (73 percent) had received Project Liberty services at a site inside of New York City. A total of 197 (44 percent) reported being in immediate danger during the World Trade Center attacks, 153 (34 percent) reported losing a family member or friend, 103 (23 percent) reported losing their job, and 101 (22 percent) reported being involved in rescue efforts.

Respondents from the brief questionnaire and telephone interview samples did not differ significantly with respect to age, gender, race or ethnicity, risk category, or preferred language. Although this was a sample of convenience, as noted in a companion article in this issue of Psychiatric Services, individuals who participated in this study generally resembled those who received Project Liberty services ( 14 ).

Predictors of return to preattack functioning

Among respondents who reported their functioning in the month before the World Trade Center attacks, several reported good or excellent functioning in the following domains: 377 of 433 (87 percent) in handling daily household activities, 343 of 413 (83 percent) in functioning in job or school, 363 of 439 (83 percent) in maintaining relationships with family and friends, 357 of 440 (81 percent) in taking care of physical health, and 317 of 412 (77 percent) in staying involved in community activities. A total of 232 of 430 (54 percent) noted that Project Liberty helped a lot in terms of returning them to preattack functioning, and an additional 163 of 430 (38 percent) said that it helped them somewhat. (Note: this item asks about Project Liberty in general and was asked of both study samples. It is different from the questions about coping strategies that specifically refer to support from the counselor; these questions were asked only of the telephone interview sample and are discussed below.)

Criterion 1.Table 1 provides results of logistic regression predicting return to functioning after the attacks in the five functional domains among those who reported good or excellent preattack functioning. As shown in Table 1 , well over half of respondents reported a return to predisaster levels of functioning in each domain. Specifically, 172 of 315 participants (55 percent) in the job or school domain, 245 of 362 (68 percent) in the family or friends domain, 230 of 375 (61 percent) in the daily activities domain, 225 of 356 (63 percent) in the physical health domain, and 197 of 315 (63 percent) in the community activities domain. In terms of demographic characteristics, African Americans were more likely than respondents of all other races to report satisfactory return to preattack functioning in each domain, except for the job or school domain. Also, those who preferred using the English language were more likely than those who preferred using another language to return to their preattack level of good or excellent functioning in the job or school domain. Those receiving Project Liberty services inside of New York City were also more likely than those receiving services outside of the city to return to preattack levels of functioning in the job or school domain and the domain involving relationships with family and friends. Age, gender, and ethnicity (Hispanic compared with non-Hispanic) did not significantly predict return to preattack functioning levels.

|

Exposure to the World Trade Center attacks was associated with being less likely to return to preattack levels of good or excellent functioning in the job or school domain. Respondents who lost a family member or friend were less likely to return to preattack functioning levels in the daily household activities domain, and those who lost a job were about half as likely to return to preattack functioning levels in the domains involving daily household activities and community activities ( Table 1 ).

Criterion 2. Most of the logistic regression models that examined various domains (that is, job or school, physical health, community involvement) did not reach statistical significance, and those that did (that is, daily activities and family relationships) had very little predictive value (R 2 =.045 and .051, respectively). However, loss of family or friends approached significance for three of the five models (daily activities, physical health, and community involvement), and job loss and being a rescue worker were statistically significant predictors in the models for daily activities and family relationships, respectively.

Factors helpful in returning to preattack functioning

Almost two-thirds of respondents who were interviewed by telephone identified support from their Project Liberty counselor as helping a lot in regaining their functioning ( Table 2 ). More than half cited helping other people, their religious and spiritual beliefs, and getting support from friends or family as factors that helped a lot. Also notable, nearly half said having a sense of humor, stronger commitment to life or community, and thoughts such as "Life is very precious" and "Things could be worse" helped a lot.

|

a All data were not available for all participants.

Discussion

Provider reports indicated that there was a high rate of posttraumatic reactions among Project Liberty service recipients ( 15 ). Yet we still found a high rate of return to predisaster levels of functioning in this group, similar to that reported for the general population ( 10 , 11 , 12 ). Across five functional life domains, more than half of the respondents who reported good or excellent functioning levels before the attack reported that they had returned to good or excellent functioning levels after the attack. Sobering, however, is the observation that substantial numbers of affected individuals who were functioning well before the attacks still had not regained their footing more than a year later.

African Americans were two to four times more likely than Caucasians to report return to good or excellent functioning in all domains. Also of note, disproportionately more African Americans used Project Liberty services than would have been expected on the basis of census data ( 16 ). This finding is in contrast to that of Boscarino and colleagues ( 11 ), who determined that significantly fewer African Americans sought mental health counseling as a result of the attacks. Religious and spiritual support may be greater among African Americans, and there may be greater support structures within African-American families and cultural communities ( 17 , 18 ).

Job loss had a pervasive impact on ability to return to adequate functioning in two of four functional life domains. Loss of work not only creates enduring financial hardship for victims but also eliminates the stability of routine and personal fulfillment that usually serve as protective factors against depression, grief, and other traumatic influences ( 19 , 20 ). Response to future terrorist attacks should, at the very least, monitor job loss and should consider using a means for rapidly facilitating meaningful and gainful employment for disaster victims as an important component of mental health interventions. Additionally, crisis counselors should be alert to problems experienced by those with the highest exposure and those who have lost a friend or family member. These individuals should be assessed to determine whether they require more intensive targeted interventions than those provided by a brief crisis intervention.

Because so few people reported poor functioning at the time of the survey, we had little statistical power to find meaningful predictors, although losing a family member or friend seemed to have been the variable most suggestive of an effect. This is consistent with other reports that suggest that losing a loved one can have a profound and lasting impact on functioning ( 21 ).

Our study found that more than 90 percent of those surveyed indicated that Project Liberty helped them as they tried to regain normalcy. Furthermore, among the variety of coping mechanisms that individuals found helpful, support from their Project Liberty counselor ranked highest. This suggests that Project Liberty was successful in its goal to reach individuals, provide brief crisis counseling, and help them to return to preattack levels of functioning, although we recognize that social desirability and sample self-selection may have played a part in such high approval ratings. However, a variety of other coping mechanisms were also endorsed by a majority of respondents as being at least somewhat helpful. Support from friends or family is widely appreciated as important and was endorsed here. Other strategies that were important are not as well known by mental health professionals. These included helping other people, religious and spiritual beliefs, a sense of humor, and a variety of positive attitudes or thoughts. Mental health interventions often focus mostly on reducing negative attitudes, thoughts, and emotions, although enhancing positive ones may be equally, if not more, important.

This study has several important limitations. Data were collected from only a subset of Project Liberty service recipients. This restriction may limit generalizability of our results, particularly for those who were not seeing benefits from Project Liberty services and subsequently discontinued crisis counseling. We obtained interviews and questionnaire data over an 11-month period by using a convenience sample in an observational study design. This cross-sectional sampling resulted in appraising individuals who had differing lengths of participation in Project Liberty and at different times after their initial visits, which could affect change in levels of functioning because those who had received Project Liberty services for longer periods may have been more likely to return to predisaster functioning. Further studies should look at the relationship between time in treatment and likelihood of return to predisaster functioning. Our outcome measures also reflected respondents' self-reported changes, which may not have been consistent with behaviorally observed outcomes. Additionally, self-report of functioning before the attacks was provided retrospectively. The application of multiple statistical tests also increased the type I error rate; therefore results need to be interpreted cautiously. Despite these limitations, we believe this study provided some interesting and provocative results.

Conclusions

Sixteen months or more after the terrorist attacks, more than one-third of the service recipients sampled who had good or excellent preattack functioning still had not regained that level of functioning. African Americans reported greater resilience than respondents from other racial groups with respect to returning to good preattack functioning in four of five life domains. Loss of a job was the exposure variable with the greatest impact on failure to regain good preattack levels of functioning, suggesting that responses to future terrorist attacks should provide employment opportunities for victims. Efforts should be directed toward facilitating meaningful employment as rapidly as possible for those who lose their jobs.

Attention should also be given to those who lose a loved one, who were among the most likely to still be functioning poorly two years after the attacks. Additionally, religion and spirituality as well as positive attitudes and thoughts (for example, having a sense of humor and having stronger commitments to life and community) were endorsed as helpful by a majority of respondents. Counseling focus should include support for a broad variety of coping mechanisms, including religious and spiritual coping for those for whom this is relevant, as well as facilitation of positive attitudes, thoughts, and emotions.

Acknowledgments

This evaluation was funded by grant FEMA-1391-DR-NY (titled "Project Liberty: Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program") to New York State from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration administered the grant. The authors express their appreciation to George Allen, Ph.D.

1. Felton C: Project Liberty: a public health response to New Yorkers' mental health needs arising from the World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 79:429-433, 2002Google Scholar

2. Covell NH, Essock SM, Felton CJ, et al: Characteristics of Project Liberty clients that predicted referrals to intensive mental health services. Psychiatric Services 57: 1313-1315, 2006Google Scholar

3. Norris FH, Donahue SA, Felton CJ, et al: A psychometric analysis of Project Liberty's Adult Enhanced Services Referral Tool. Psychiatric Services 57:1328-1334, 2006Google Scholar

4. Herman D, Felton C, Susser E: Mental health needs in New York state following the September 11 attacks. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 79:322-331, 2002Google Scholar

5. Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 346:982-987, 2002Google Scholar

6. Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, et al: Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: findings from the National Study of Americans' Reactions to September 11. JAMA 288:581-588, 2002Google Scholar

7. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al: A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. New England Journal of Medicine 345:1507-1512, 2001Google Scholar

8. Melnick TA, Baker CT, Adams ML, et al: Psychological and emotional effects of the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center—Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, 2001. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 51:784-785, 2002Google Scholar

9. Effects of the World Trade Center Attack on New York City Public School Students: Initial Report to the New York City Board of Education. New York, Applied Research and Consulting and Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, 2002Google Scholar

10. Galea S, Vlahov D, Resnick H, et al: Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology 158:514-524, 2003Google Scholar

11. Boscarino JA, Adams RE, Figley CR: Mental health service use 1-year after the World Trade Center disaster: implications for mental health care. General Hospital Psychiatry 26:346-358, 2004Google Scholar

12. Boscarino JA, Galea S, Adams RE, et al: Mental health service and medication use in New York City after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack. Psychiatric Services 55:274-283, 2004Google Scholar

13. DeLisi LE, Maurizio A, Yost M, et al: A survey of New Yorkers after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:780-783, 2003Google Scholar

14. Jackson CT, Allen G, Essock SM, et al: Clients' satisfaction with Project Liberty counseling services. Psychiatric Services 57:1316-1319, 2006Google Scholar

15. Jackson CT, Allen G, Essock SM, et al: Clusters of event reactions among recipients of Project Liberty mental health counseling. Psychiatric Services 57:1271-1276, 2006Google Scholar

16. Donahue SA, Covell NH, Foster MJ, et al: Demographic characteristics of individuals who received Project Liberty crisis counseling services. Psychiatric Services 57: 1261-1267, 2006Google Scholar

17. Parks FM: The role of African American folk beliefs in the modern therapeutic process. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 10:456-467, 2003Google Scholar

18. Stevenson HC, Renard G: Trusting ole' wise owls: therapeutic use of cultural strengths in African-American families. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 24:433-442, 1993Google Scholar

19. Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC: Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition: two prototypes for depression. Clinical Psychology Review 12:527-562, 1992Google Scholar

20. Pasick RS: Raised to work, in Men in Therapy: The Challenge of Change. Edited by Meth RL, Pasick RS. New York, Guilford, 1990Google Scholar

21. Shear KM, Jackson CT, Essock SM, et al: Screening for complicated grief among Project Liberty service recipients 18 months after September 11, 2001. Psychiatric Services 57:1291-1297, 2006Google Scholar