The Treatment Relationship in Peer-Based and Regular Case Management for Clients With Severe Mental Illness

The past decade has witnessed a virtual explosion in the number and type of peer-based interventions aimed at engaging persons with severe mental illness into care and promoting their recoveries within traditional clinical and rehabilitative venues. Although existing research on such interventions remains sparse, it suggests the outcomes to be at least equivalent to those obtained through regular services ( 1 , 2 , 3 ) and in some instances superior ( 4 , 5 ). Although researchers and practitioners alike have hypothesized that the success of these interventions is owed at least in part to enhanced positive qualities within peer provider-client relationships, few investigations have rigorously examined this claim with quantitative empirical approaches.

A notable exception is the pioneering work of Solomon and colleagues ( 6 ), who compared peer-provided and usual case management services within a randomized clinical trial, hypothesizing that levels of favorable working alliance and service outcomes would be higher in the peer condition after two years. Although between-condition results proved equivocal in terms of working alliance, regression analyses showed that working alliance favorably predicted quality of life, treatment satisfaction, client symptom levels, and attitudes regarding medication compliance across conditions. The authors interpreted their findings as suggesting equivalence of treatment conditions with respect to working alliance at two years' time and proposed that future research examine aspects of peer-based treatment relationships earlier in the treatment process.

Building on the results and insights of researchers such as Solomon and colleagues, our primary purpose with this investigation was to study the effects of peer-provider-based case management services on treatment relationship dimensions and engagement for clients with severe mental illness early in the treatment process. Moreover, we sought to determine the extent to which positive treatment relationship dimensions predicted motivation for and use of other community-based services within a population of persons noted for their use of emergency and institution-based services. Our research questions were whether clients receiving services from peer providers would have more positive perceptions of dimensions of the treatment relationship at six months into treatment—including positive regard, empathy, and unconditional acceptance—than those receiving services from usual case managers, whether clients receiving services from peer providers would show higher levels of attendance over the first six months of treatment than those receiving services from usual case managers, and whether six-month treatment relationship dimensions would positively predict motivation for and use of community-based services at a 12-month follow-up.

To assess these questions, we conducted a study from July 2001 to June 2003, using a 2×2 prospective longitudinal randomized clinical trial design with two levels of intervention (services with peer or regular providers) and two assessment periods (six and 12 months). Participant interviews included assessments of treatment relationships, service use, and motivation, whereas provider questionnaires included ratings of participants' initial engagement in treatment, as well as monthly levels of attendance at case management meetings.

Methods

Participants

The human investigations review committee of the sponsoring institution approved all study protocol, procedures, and personnel before data collection. Fifty-three women and 84 men participated in the study, with ages ranging from 20 to 63 years and a mean±SD age of 41±9 years. Eighty-nine participants described their racial ancestry as Caucasian, 39 as African American, and nine as other, and across all participants, nine identified themselves as being of Hispanic ethnicity. Diagnostic information was unavailable for five participants. All others carried a diagnosis of severe mental illness, and about 70 percent had a co-occurring substance use disorder. Participants' diagnoses, which were equivalent across groups, are summarized in Table 1 .

|

a Most participants had more than one diagnosis. Data were missing for five participants (three in the peer provider group and two in the control group).

Sixty-eight participants were randomly assigned to an experimental condition in which they received 12 months of case management services from peer providers partnered with assertive community treatment teams. Sixty-nine participants were assigned to a control condition in which they received services as usual, but not from peer providers participating in this program.

Measures

Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory (BLRI). The BLRI ( 7 ) is a 64-item self-report questionnaire for assessing dimensions of the client-counselor relationship from the client's perspective and is designed to determine favorable contexts for therapeutic change. Researchers have used the BLRI across numerous investigations of traditional psychotherapy, showing it to be a valid and reliable measure of the provider-client relationship ( 8 ) and highly correlated with other popular measures of therapeutic alliance ( 9 ), such as the Working Alliance Inventory ( 10 ). BLRI respondents rate their level of agreement with statements across subscale domains on a 6-point scale that ranges from definitely false, 1, to definitely true, 6. Subscale domains in this investigation included items pertaining to providers' positive regard ("She/he feels a true liking for me"), empathy ("She/he usually senses or realizes what I am feeling"), and unconditionality ("How much she/he likes or dislikes me is not altered by anything that I tell her/him about myself").

For the purposes of this project, we first administered the BLRI to ten pilot participants and then made minor modifications to the items to render the language more accessible to the target population. For example, an item reading "She/he appreciates exactly how the things I experience feel to me" was revised to read "She/he appreciates how my experiences feel to me." We revised nine other items in a similar fashion and deleted two others because they proved difficult for pilot participants to comprehend. An example of a deleted item is "I can (or could) be openly critical or appreciative of her/him without really making her/him feel any differently about me." We found high to moderate internal consistency reliabilities for BLRI subscales in this investigation, with alpha coefficients ranging from .95 to .54.

Addiction Severity Index (ASI). The ASI ( 11 ) is a structured interview designed to assess the severity of potential treatment obstacles across areas typically affected by alcohol and drug use disorders, including psychiatric and social considerations. For the purposes of this project, we used only the alcohol and drug use ASI subscales. The alcohol use subscale assesses the frequency and severity of use in the past 30 days, whereas the drug use subscale assesses the frequency and severity of use of various substances (cocaine and heroin, for example) during the same period. The ASI has been rigorously evaluated and shown to be both a valid and reliable means of assessing drug and alcohol use and its consequences ( 12 ).

Service use. To assess participants' use of services for psychiatric, alcohol, and substance abuse problems, we included a 26-item self-report measure of service use in which participants indicated the number of days in the past 30 in which they used particular service modalities (day hospital programming for psychiatric problems, outpatient treatment for drug use, and so on).

Initial engagement and attendance. Providers across conditions rated their clients' levels of prior treatment engagement using an item from the Level of Care Utilization System ( 13 ) according to a 5-point scale ranging from 1, optimal engagement, to 5, unengaged. To assess participants' attendance patterns, providers completed a brief monthly tracking form that included an estimate of the total number of contacts with their clients over the past 30 days.

Procedures

Participant selection criteria included a primary diagnosis of severe mental illness (schizophrenia spectrum disorder, major mood disorder, or both) and treatment disengagement. Investigators identified prospective participants through the local mental health authorities of two Connecticut cities. Interested persons were invited to participate in an interview in which they received a full description of the project and its goals and learned about possible risks and benefits. If still interested after the interview, participants were asked to complete an informed consent form. If consent was granted, investigators randomly assigned participants to either the experimental (peer provider) or control (regular treatment) condition.

Program context. All peer staff had publicly disclosed histories of severe mental illness, and some had disclosed histories of co-occurring drug use disorders. Peer staff received broad-based training concerning the provision of case management services from professional and peer health care staff at Connecticut agencies funded through the state's Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. These training sessions focused on identifying peer providers' individual areas of strength and used past experiences with recovery as a tool for understanding, role modeling, and hope building for others. In addition, through lectures and supervision, the training spanned various topics, including outreach and engagement; ethical guidelines, such as confidentiality and professional boundaries; local community resources, including advocacy agencies; and record keeping. The overarching goal of didactic training was to provide peer staff with meaningful, comprehensive, and balanced instruction on key areas of case management practice. Because of various backgrounds and experiences among peer staff, however, the training also strove to accommodate the individual needs and style of each peer staff member.

All peer staff worked as providers within the Connecticut Peer Engagement Specialists project, a four-site statewide investigation at public mental health centers in three Connecticut towns and through contract with a nonprofit agency in a fourth town. Community-based program sites provided assertive community treatment at the mental health centers and a psychosocial program at the nonprofit agency. Peer providers at all sites carried an average caseload of ten to 12 clients and received supervision from clinical supervisors.

Regular providers participating in the study worked alongside peer providers participating in the study on the same treatment teams and carried about twice the average peer provider caseload.

Statistical analyses. In the first set of analyses, we used a series of t tests to evaluate differences between conditions across BLRI subscales (positive regard, empathy, and unconditionality) at six- and 12-month assessment periods, with squared point-biserial (r pb2 ) correlations as estimates of effect size. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) evaluated between-condition differences in client contacts with case managers over the first six months of treatment meetings, with partial η2 as an effect size estimate. In the second set of analyses, we used simple linear regression to predict 12-month motivation for and use of community-based psychiatric and drug use rehabilitation services from six-month treatment relationship dimensions. The R 2 statistic served as an effect size estimate.

Results

Between-condition analyses

Results of t tests yielded significant results across BLRI subscales at the six-month evaluation period only. As presented in Table 2 , at six months all subscales of the BLRI differed significantly across conditions, with participants in the peer provider (experimental) condition reporting more positive provider relationship qualities than those in the control condition.

|

As shown in Table 2 , the project resulted in an average attrition of 25 percent across assessment periods with respect to BLRI data. Chi square analyses showed that missing data were not related to condition at six- or 12-month evaluation periods.

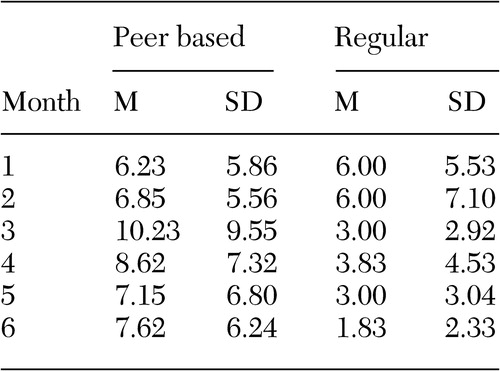

Results of repeated-measures ANOVA of differences in client case management attendance within the overall sample during the first six months of treatment proved equivocal. However, the same analysis conducted on a subsample of 25 clients at six months rated by clinicians as the least engaged in treatment yielded a significant interaction of condition and time (F=7.15, df=1 and 23, p<.05, η2 =.24), where those in the experimental condition showed increasing contacts with their case managers over the six-month period and those in the control condition showed decreasing contacts ( Table 3 ). Further analyses found no association between attendance levels and BLRI subscale scores.

|

Predictive analyses

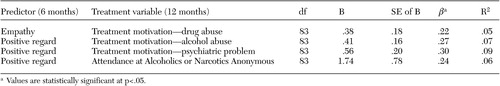

As indicated in Table 4 , results of linear regression analyses with six-month BLRI positive regard and empathy subscales as predictors across both conditions proved significant for 12-month self-reported treatment motivation for psychiatric, alcohol, and drug use problems, and attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings. There were no between-group differences for 12-month motivation or service use data.

|

Discussion

With respect to our first research question, clients in the experimental condition reported feeling more liked, understood, and accepted by their providers than those in the control condition six months after entering treatment, and these effects disappeared at 12 months. With respect to our second question, whether treatment attendance would improve in the first six months, participants in the experimental condition showed increasing contacts with providers during the early phase of treatment and participants in the control condition showed decreasing contacts. For our third question, we found that across conditions, feeling more liked and understood at six months predicted higher levels of self-reported motivation for treatment, as well as use of AA and NA treatment, at 12 months.

These findings appear to support researchers' and practitioners' assertion of differences between peer-based and regular case management treatment relationships ( 4 , 14 ), as well as Solomon and colleagues' ( 6 ) prediction that such differences emerge earlier in the treatment process and eventually disappear as regular services catch up in building stronger treatment relationships. In terms of practice, this pattern seems to reflect peer providers' abilities to quickly establish working alliances with clients, as well as their strengths at engaging into treatment persons with severe mental illness.

Moreover, most participants in this investigation had psychiatric and co-occurring alcohol or substance use disorder, a condition characterized by at least one group of investigators as "a significant disorder of engagement" ( 15 ). Given the fundamental task of engagement within evidenced-based integrated programming for persons with co-occurring disorders ( 16 ), our findings strongly suggest a valued role for peer providers in forging therapeutic connections with persons typically considered to be among the most alienated from the health care service system.

Another question that follows from the study results is whether peer-provided services promote collaboration and moderate what the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health report ( 17 ) characterizes as the tendency of the mental health system to bewilder and overwhelm. Full participation by consumers in the planning and delivery of services has been identified as a cardinal feature of recovery-based treatment. Perhaps peer providers are able to buffer the alienating aspects of service delivery and facilitate consumer participation.

Although the study was not an investigation of treatment outcome, our findings suggest avenues through which positive treatment relationships could ultimately lead to enhanced outcomes via enhanced treatment engagement, as well as through increased motivation for, and use of, peer-based treatments in particular. Although positive links between treatment relationship and outcome have long been documented by clinical investigators ( 18 ), only recently have they been captured within quantitative community-based research ( 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ); however, the mechanisms by which these links obtain are still unclear. Findings from this study suggest that providers' positive regard for and understanding toward clients contribute to clients' interest and pursuit of further treatment. Of course, if and how further treatment ultimately leads to enhanced clinical outcomes are questions for future research.

This investigation was limited in several ways that merit attention. First, client self-report served as our primary data source concerning treatment relationships, as well as motivation for and use of outside treatments. In our efforts to lessen the burden upon busy providers, we did not obtain their ratings of treatment relationships, which are known to predict outcome for persons with severe mental illness ( 21 ). Nevertheless, psychotherapy research has shown that clients' ratings of the treatment relationship are also robust predictors of outcome ( 18 ), and it is up to future research to specify the strongest predictors of outcome within peer-based treatment relationships.

Second, although this study produced statistically significant results, mean BLRI scores in both study conditions were all within the 4- to 5-point range, and analyses yielded only modest effect sizes. Because the clinical relevance of these findings could be more fully depicted, future work should strive to relate increments of relationship quality to appropriate indices of clinical progress and outcome.

Third, the size of our sample was small and suffered from an average rate of attrition of about 25 percent from the program across assessment periods with respect to BLRI data, possibly limiting the generalizability and statistical validity of findings. Although larger-scale investigations may help address generalizability, statistical validity appears to be less of a problem here, as our research yielded statistically significant results. Furthermore, studies of persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders are typically plagued by high rates of attrition, and chi square analyses in this study suggested that the observed attrition was not related to condition at either the six- or 12-month follow-up.

Fourth, because peer providers had lower caseloads than regular providers and could defer the task of setting limits with clients on such things as treatment contracts and attendance, it is entirely possible that the nature of the work contributed to the observed positive findings for peer-provided services. Future studies designed to compare similar units and types of services between regular and peer-provided services may yield information on the possible interaction between service and provider variables.

Fifth, as noted by various authorities in the area ( 23 , 24 ), consumer and nonconsumer providers have distinct patterns of service provision, which were not considered in this study. It is possible that having peer and regular providers on the same treatment teams introduces a contamination not only to the potential study of such distinctions but also to other variables within this study, where all providers attended the same meetings and could freely interact and share practice activities. Future research might do well to document peer versus regular provider practice distinctions—linking them to suitable client outcomes—and better control for service context.

Conclusions

This research suggests that during the early stages of treatment, peer providers possess distinctive skills in communicating positive regard, understanding, and acceptance to their clients, as well as a facility for increasing participation in needed treatment among the most disengaged. Although it remains unclear whether and how such skills foster improved outcomes in case management services, they do suggest a valued role for persons who have "been there" in engaging into treatment those who are "there" now.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the Yale Institution for Social and Policy Studies. The peer-based treatment option was sponsored by the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

1. Chinman MJ, Rosenheck R, Lam JA, et al: Comparing consumer and nonconsumer provided case management services for homeless persons with serious mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:446-453, 2000Google Scholar

2. Lyons JS, Cook JA, Ruth AR, et al: Service delivery using consumer staff in a mobile crisis assessment program. Community Mental Health Journal 32:33-40, 1996Google Scholar

3. Solomon P, Draine J: One-year outcomes of a randomized trial of consumer case managers. Evaluation and Program Planning 18:117-127, 1995Google Scholar

4. Felton CJ, Stastny P, Shern D, et al: Consumers as peer specialists on intensive case management teams: impact on client outcomes. Psychiatric Services 46:1037-1044, 1995Google Scholar

5. Davidson L, Chinman MJ, Kloos B, et al: Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: a review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 6:165-187, 1999Google Scholar

6. Solomon P, Draine J, Delaney M: The working alliance and consumer case management. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:126-134, 1995Google Scholar

7. Barrett-Lennard GT: Dimensions of therapist response as causal factors in therapeutic change. Psychological Monographs 76(43, whole no 562), 1962Google Scholar

8. Simmons J, Roberge L, Kendrick BS: The interpersonal relationship in clinical practice: the Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory as an assessment instrument. Evaluation and the Health Professions 18:103-112, 1995Google Scholar

9. Salvio M, Beutler LE, Wood JM, et al: The strength of the therapeutic alliance in three treatments for depression. Psychotherapy Research 2:31-36, 1992Google Scholar

10. Horvath AO, Greenberg LS: Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology 36:223-233, 1989Google Scholar

11. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: An improved evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26-33, 1980Google Scholar

12. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al: New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 173:412-423, 1985Google Scholar

13. American Association of Community Psychiatrists: Level of Care Utilization System for Psychiatric and Addiction Services, Adult Version 2000. Pittsburgh, St Francis Medical Center, 2000Google Scholar

14. Solomon P, Draine J: Perspectives concerning consumers as case managers. Community Mental Health Journal 32:41-46, 1996Google Scholar

15. Sekerka R, Goldsmith RJ, Brandewie L, et al: Treatment outcome of an outpatient treatment program for dually-diagnosed veterans: the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 31:85-94, 1999Google Scholar

16. Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, et al: Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:469-476, 2001Google Scholar

17. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

18. Horvath AO, Symonds D: Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology 38:139-149, 1991Google Scholar

19. Chinman MJ, Rosenheck R, Lam JA: The case management relationship and outcomes of homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:1142-1147, 2000Google Scholar

20. Gehrs M, Goering P: The relationship between the working alliance and rehabilitation outcomes of schizophrenia. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 18:43-54, 1994Google Scholar

21. Neale MS, Rosenheck RA: Therapeutic alliance and outcome in a VA intensive case management program. Psychiatric Services 46:719-721, 1995Google Scholar

22. McCabe R, Priebe S: The therapeutic relationship in the treatment of severe mental illness: a review of methods and findings. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 50:115-128, 2004Google Scholar

23. Paulson R, Herinckx H, Demmler J, et al: Comparing practice patterns of consumer and non-consumer mental health service providers. Community Mental Health Journal 35:251-269, 1999Google Scholar

24. Solomon P, Draine J: Service delivery differences between consumer and nonconsumer case managers in mental health. Research on Social Work Practice 6:193-207, 1996Google Scholar