Strategies for Coping With Cognitive Impairments of Clients in Supported Employment

Supported employment for persons with severe mental illness is now widely accepted as an evidence-based practice ( 1 ). Despite the strong evidence for supported employment, little is known about how it actually works or, more specifically, what employment specialists do to make supported employment work. What little is known is gleaned from published studies about the specific components that define supported employment, such as rapid job search, focus on competitive employment, follow-along supports, attention to clients' preferences, and integration with clinical treatment ( 2 ). In particular, there is a paucity of research examining how common illness-related symptoms and impairments are managed in supported employment and the effectiveness of different approaches.

One such question is how employment specialists manage cognitive impairments among persons with severe mental illness. Cognitive functioning is highly relevant to vocational rehabilitation for several reasons. First, cognitive impairment is common among persons with severe mental illness and is related to a range of functional outcomes ( 3 , 4 ), including work ( 5 ). Second, cognitive impairment is related to worse work outcomes and more intensive vocational services for clients receiving supported employment ( 6 , 7 ), suggesting that employment specialists are involved in helping their clients compensate or overcome the effects of these impairments on work. However, we are not aware of efforts to evaluate employment specialists' understanding of cognitive impairments in severe mental illness and their effects on work.

To understand how to minimize the effects of cognitive impairment at the workplace and how to maximize supported employment outcomes, information is needed about how employment specialists deal with these limitations of their clients. Specifically, research is needed to explore the range of strategies employment specialists use to help their clients cope with the effects of cognitive impairments and the perceived effectiveness of these strategies. Such research could both identify potentially useful coping strategies and pave the way to examining the effects of those strategies on work outcomes. This study was designed to take this first step toward understanding how employment specialists help their clients deal with cognitive impairments at the workplace.

Methods

The study was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. For the first stage, participants provided written informed consent; the second stage qualified for exemption of written informed consent because the data were derived from an anonymous survey. The employment specialist interview was carried out in two stages from June 2003 through December 2004. In the first stage, we surveyed 25 employment specialists from six supported employment programs in the New York City area that were implementing supported employment as broadly defined by evidence-based practice ( 1 ). Program elements included minimal prevocational assessment, no prevocational training, rapid job search based on clients' preferences, time-unlimited supports, and integration with clinical services. The six programs were selected because the first author was conducting research at the program sites and was familiar with the directors of employment services.

Employment specialists were asked to complete a survey about their use of cognitive coping strategies. The following instructions were provided: "We are interested in learning which strategies you use to help clients on the job who have difficulties with attention, motor speed, memory, or problem solving. Please write down all strategies you use under each cognitive domain. In addition, please provide examples of how you have used these strategies." No specific time frame was established for the use of the different strategies. Employment specialists recorded the strategies and examples on a survey sheet.

A large number of strategies were identified by the employment specialists, and a follow-up survey was designed to assess the frequency and perceived effectiveness of these strategies in a larger sample of employment specialists that spanned a broader geographical area. For the second stage, the directors of supported employment programs that were based on the principles described above who were known to either the first or the second author were contacted and invited to participate in the survey. Fifty employment specialists (including five from the first stage) from 11 different supported employment programs in six states anonymously completed the survey. They indicated whether or not they used each strategy (no time frame was specified), and for each strategy used, they rated its effectiveness on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating not effective and 5 indicating very effective.

Employment specialists also provided information about their educational background, the total number of clients in their caseload, and the number of their clients who were working. Educational level was coded on the basis of the Hollingshead Educational Index ( 8 ), in which a master's degree is coded as 1 (seven participants), a bachelor's degree as 2 (25 participants), a high school diploma and some college as 3 (nine participants), and a high school diploma as 4 (nine participants). None of the employment specialists had lower levels of education on this scale. Employment specialists had a mean±SD caseload of 19±8.0 clients (range= 1-33); a mean of 8±5.2 clients in the caseload, or 43 percent, were working (range=0-100 percent).

For the first stage of the study, the number of different strategies identified for each of the four domains of cognitive functioning was tallied. In the second stage, the average number of coping strategies reported by employment specialists was computed, as well as the average effectiveness of those strategies. For each strategy within each cognitive domain, the number of employment specialists who used that strategy was summed, and the average effectiveness rating given by those specialists was computed.

The average effectiveness ratings of the different coping strategies across the four cognitive domains were then examined with paired t tests. Pearson correlations were computed between the number of coping strategies reported as used by employment specialists and their perceived effectiveness, the specialist's educational level, and the percentage of clients on the specialist's caseload who were working. Partial correlations were also computed between the percentage of clients on the caseload who were working and the number of coping strategies reported by the specialist, while the analysis controlled for the specialist's educational level. Correlations were also computed between the percentage of clients on the caseload who were working and the employment specialist's educational level, while statistically controlling for the number of coping strategies reported by the specialist. Finally, the average percentage of clients on employment specialists' caseloads who were working was computed for each quartile of specialists who reported using the fewest to the highest number of coping strategies. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATISTICA, version 6.

Results

In the first stage of the study, the 25 employment specialists identified a total of 76 coping strategies for dealing with problems in the four cognitive domains: attention (18 strategies), psychomotor speed (20 strategies), memory (19 strategies), and problem solving (19 strategies). In the second stage, the 50 employment specialists reported using a mean of 47.7±16.0 coping strategies (range=12-73) and gave these strategies a mean effectiveness rating of 3.7±.6, corresponding to slightly below the anchor "effective" (score of 4).

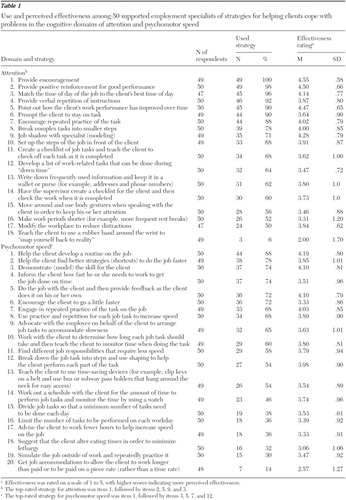

The number of specialists using each strategy and the mean effectiveness ratings are shown in Tables 1 and 2 . The five most effective strategies within each cognitive domain are noted. Employment specialists reported using the most coping strategies for dealing with difficulties in problem solving (14.5±3.9), followed by attention (13±3.4.0), memory (11.3±4.0), and psychomotor speed (11±5.7).

|

|

In terms of average effectiveness, employment specialists gave the highest ratings to coping strategies for attention (3.9±.5), followed by psychomotor speed (3.7±.7), memory (3.7±.6), and problem solving (3.7±.6). Paired t tests indicated that the mean effectiveness rating for attention was significantly higher than those for memory (t=4.3, df=48, p<.001), problem solving (t=3.0, df=40, p<.001), and speed (t=4.5, df=47, p<.001). No other differences in effectiveness ratings between the different domains were significant.

The total number of coping strategies that employment specialists reported using was significantly correlated with the mean effectiveness ratings for those strategies (r=.38, p=.007), indicating that specialists who used more coping strategies perceived those strategies to be more effective. Examples of the five most frequently used strategies for each cognitive domain are provided in the boxes on this page and the next one.

Examples of the top five coping strategies used by employment specialists for dealing with cognitive impairments in the domains of attention and psychomotor speed

Attention

1. Encouragement

"A client felt very discouraged because she had difficulty paying attention to her job despite trying hard. We developed a 'words of encouragement' list for her to read at the end of a bad work day in order to help bolster her motivation and self-esteem."

2. Positive reinforcement for good performance

"I have asked employers to compliment clients for their good work and point out their positive qualities. For example, a client working at a supermarket was employee of the month and received a $25 bonus. The client was thrilled by this."

3. Match the time of day of job to the client's best time of day

"A client had a tendency to stay up late at night and oversleep in the morning, resulting in tardiness for his morning job and, ultimately, job loss. For the client's next job, we decided on evening shift hours, which enabled him to get to work on time."

4. Verbal repetition of instructions

"I've used repetition of verbal instructions when teaching clients multistep sequential tasks, such as how to use the cash register."

5. Point out how someone's work performance has improved over time

"This is particularly effective for clients with low self-esteem and confidence. One client stated, 'I'll never learn this job.' Specific tasks that the client had mastered were pointed out by the employment specialist, which helped her stay on the job."

Psychomotor speed

1. Help the client develop a routine on the job

"Teamwork helps some clients pick up their work pace. For example, a client was working too slowly completing a food service job on his own, such as loading the refrigerator with drinks and stocking the condiments. I suggested he work as part of the food assembly team, which improved his speed considerably."

2. Help the client find better strategies to do the job faster

"The client and I developed a more efficient way of doing his job task of preparing food trays for refrigeration: we completed each component of the task for all the trays before moving on to the next part (that is, laid out six trays, filled them all, then covered them in plastic wrap, then labeled them with the date, and then loaded them for the refrigerator) rather than doing one tray at a time."

3. Demonstrate (model) the skill for the client

"A client working in the stock room of a deli got a promotion to sandwich maker. He had difficulty with the sequence of making the sandwich, so I filled several sandwich orders with him watching the sequence of toasting the bread, putting on the condiments, slicing the meat and the cheese, putting on the onions, and so forth. He found it useful to watch me before trying it. What was most helpful to him was realizing that I needed practice too."

4. Inform the client how fast he or she needs to work in order to get the job done on time

"The client took a lot of time delivering packages. She deviated from the best route and took 30 minutes to do a ten-minute job. I worked with the client by timing deliveries, setting a goal of a certain amount of time per delivery, with the ultimate goal of ten minutes per delivery. She began to stick to the fastest delivery route."

5. Do the job with the client, and then provide feedback when the client does it on his or her own

"I have done this with cash register training. We do the task together. I then asked the client to repeat the steps in sequence both verbally and by placing his or her fingers correctly on keys until each step is mastered. We do this at the workplace when customers are not present."

Examples of the top five coping strategies used by employment specialists for dealing with cognitive impairments in the domains of memory and problem solving

Memory

1. Encourage the client to ask questions when given instructions about a task

"I encourage clients to ask me questions. I'll say 'Everyone has questions when they learn something new. Tell me yours.' "

2. Encourage the client to remember the information

"In learning how to use a cash register, I encourage clients to remember information by having them write down sequential steps, study them at home, and tape the instructions beside the cash register."

3. Model (demonstrate) how to do the job

"I do the job with the client by my side. I do this so I can get my own sense of the job, so I can show the client how I learn the job, and so I can provide true, understandable, realistic feedback to the client when he or she does it."

4. Break complex tasks into smaller steps.

"A client who was promoted from busing tables to hosting tended to seat people on only one side of the restaurant rather than both sides. We developed a seating chart together, numbering the tables as follows: 1 on the right, 2 on the left, 3 on the right, and so forth, so the client had a standard sequence of steps for seating customers."

5. Encourage repeated practice of job tasks

"A client had difficulty remembering how to make beds in a hospital housekeeping position. We reviewed the most efficient bed-making strategy, and he then practiced at home with his mother's help."

Problem solving

1. Problem solve with the client how to handle problems

"I always encourage the client to think through problems out loud, so I can see where he or she is stuck. We work together from that point to solve the problem."

2. Encourage the client to call the employment specialist to help solve a problem

"I always provide my card so clients can keep my number in their wallet. I encourage them to call by saying 'You never bother me; I'm glad to have you call. I'm glad to help. I can help you work this out. Even if I am not at my desk, I will always return your call.'"

3. Prompt the client to discuss the problem with the supervisor

"I encouraged a client to meet with her supervisor about a coworker she found difficult to work with. Her supervisor assured her that she was aware this person was difficult and that she would deal with the coworker if things got to be a problem."

4. Help the client develop a routine to stay organized

"I suggested to one client who routinely overslept to prepare for work the night before: he showered, packed his lunch, counted out his carfare, and arranged his clothes at night which helped him get out the door faster in the morning."

5. Try to anticipate problems and develop strategies to deal with them

"I make statements like 'Everyone has trouble with this task' or 'Many other people have complained about doing this. Let's figure out how you can get through it.' 'This employer is particular about … being on time … keeping the cash drawer accurate … how to speak with customers. So let's work together on tasks that concern you.'"

We explored whether there were common strategies used across the four cognitive domains. Among the five most effective strategies within each domain, common strategies across domains were identified. Modeling was used in three strategies, including attention, item 9; psychomotor speed, item 3; and memory, item 3. Developing a routine was used in three strategies, including psychomotor speed, item 1; memory, item 17; and problem solving, item 4. Positive reinforcement was used in three strategies, including attention, items 2 and 5, and psychomotor speed, item 12. Practice was used in two strategies, including psychomotor speed, item 7, and memory, item 5.

Interestingly, two of these specific strategies were also included in the full list of coping strategies for all four cognitive domains, including modeling (attention, items 9 and 10; psychomotor speed, item 3; memory, item 3; and problem solving, item 19) and practice (attention, item 7; psychomotor speed, items 7, 8, 12, and 19; memory, item 5; and problem solving, item 9). A third specific strategy was also reported as useful in all four cognitive domains, breaking the task down into steps (attention, item 8; psychomotor speed, item 12; memory, item 4; and problem solving, item 8). Encouragement was a strategy cited a total of seven times across all four cognitive domains but with different meanings; for example, social reinforcement (attention, item 1) and provision of instructions (problem solving, item 2). This finding suggests that encouragement does not represent a single strategy.

We evaluated whether the number of coping strategies that employment specialists used was related to their educational level and the employment status of their clients. Employment specialists who used more coping strategies had significantly higher levels of education (r=-.34, p=.017) and a greater percentage of employed clients on their caseloads (r=-.32, p=.03). Employment specialists with higher educational levels also had a greater percentage of clients on their caseloads who were working (r=-.40, p=.006).

When the analysis controlled for the educational level of the employment specialist, the partial correlation between the number of coping strategies used and the percentage of clients working was significant (partial r= .39, p=.008). However, when the analysis controlled for number of coping strategies, the partial correlation between educational level and percentage of clients working was not significant. Thus the number of coping strategies used by employment specialists, but not their educational level, was uniquely predictive of the proportion of clients on their caseloads who were working.

To examine the relationship between the number of coping strategies used and the percentage of clients working, we divided the sample of employment specialists into quartiles on the basis of the number of coping strategies they reported using. The bottom quartile of employment specialists used a mean±SD of 25.2±7.7 strategies (range=12-34) and reported a mean of 35.3±28.0 percent of clients working range= 0-100 percent). The top quartile of employment specialists used a mean of 55.8±2.9 strategies (range=62-73) and reported a mean of 57.8±21.4 percent of clients working (range=33 to 199 percent).

We explored whether excluding employment specialists with relatively low caseloads from the analysis altered the results. Parallel analyses were performed for the subsets of employment specialists who had caseloads of more than ten clients (N=39) and caseloads between 15 and 30 (N=32). Both sets of analyses indicated a similar pattern of results, including differences between the perceived effectiveness of coping strategies for different domains of cognitive functioning, the association between number of coping strategies and their perceived effectiveness, and the associations between number of strategies, educational level of the specialist, and the percentage of employed clients on the caseload.

Discussion

Supported employment specialists reported using an average of 48 different coping strategies to help their clients deal with cognitive limitations. Because the survey did not specify a time frame, it is unclear whether the specialists used the strategies they endorsed with clients on their current caseloads or whether they had used the strategies during their work as a supported employment specialist, or a combination. On average, coping strategies were rated as just below effective; strategies for coping with problems in attention were rated as significantly more effective than strategies for dealing with problems in psychomotor speed, memory, and problem solving. Thus employment specialists appear to be aware of the problem of cognitive impairments among their clients, they report using a wide range of strategies to overcome the effects of such impairments on work, and they perceive these efforts to be useful.

The active involvement of employment specialists in dealing with cognitive limitations of their clients is consistent with research showing that clients with more cognitive impairments receive more supported employment services per hour of competitive work ( 7 ) and, as hypothesized by McGurk and Mueser ( 5 ), that some of these services are geared toward helping clients learn work-related skills or teaching them how to compensate for the effects of cognitive impairments at the workplace.

Employment specialists endorsed using a diverse range of strategies to help clients deal with their cognitive impairments, although several common approaches emerged. Among the most widely used—and the most useful—strategies across the four cognitive domains of attention, psychomotor speed, memory, and problem solving were those aimed at teaching clients skills using social learning principles, including breaking larger tasks into smaller ones, modeling, practice, and positive reinforcement and encouragement. Together these specific strategies, or shaping (that is, reinforcing successive approximations to a desired goal), appeared to be useful for overcoming problems in different cognitive domains. This is not surprising considering that impairments in different areas of cognitive functioning tend to be intercorrelated ( 9 , 10 ), and efforts to address problems in one area may well address problems in others. Furthermore, the very effective strategy of helping clients develop a routine to minimize problems in psychomotor speed, memory, and problem solving, which may be accomplished in part through the systematic application of the aforementioned social learning principles, suggests that learning tasks to the point where they become "automatic," a critical component in developing expert performance ( 11 ), may reduce the effects of cognitive difficulties at work.

Aside from the apparent utility of learning-based strategies for helping clients acquire job skills despite cognitive difficulties, several other common strategies were noted. Some strategies involved modifying the workplace environment or expectations, such as removing distracting elements, to improve attention; finding different job responsibilities that require less speed; arranging to have instructions visually displayed in the work area to reduce memory requirements; and modifying job demands to reduce the need for problem solving.

Another type of strategy used across the range of cognitive domains was teaching coping skills to clients to minimize or compensate for limitations in these areas. Such skills included teaching clients to snap a rubber band on their wrist to refocus their attention back on their job, teaching clients how to monitor their time when doing a task to improve speed, teaching clients to write down instructions for job tasks to minimize memory demands, and teaching clients to conceptualize obstacles as "problems" and then to brainstorm solutions. Still another type of strategy was for the employment specialist to develop a solution to a problem caused by cognitive impairment, such as creating specific "to do" lists for the client each day to help the client remember job tasks, helping the client find shortcuts for doing the job faster, and developing simple rules to solve problems for clients.

Although a number of different approaches to coping with cognitive difficulties were apparent, many other strategies could not be classified as belonging to a single theme, either because they were ambiguous or they could be included in multiple thematic categories. For example, "use Post-It notes" (item 16 for memory) could be taught to the client as a coping strategy for managing memory problems or implemented directly by the employment specialist as a workplace modification, or some combination thereof. In addition, even within cognitive domains there was overlap in some of the strategies cited, such as teaching the client to create specific "to do" lists for each day to help remember job tasks (item 9 for memory) and teaching clients to write down instructions for job tasks (item 10 for memory). Thus the different coping themes, and some of the strategies themselves, appear more akin to "fuzzy sets" rather than clearly demarked, nonoverlapping categories.

Even though similar or the same strategies were used to deal with problems in different domains of cognitive functioning, there were clear differences in which strategies were perceived to be most effective for the different domains. For example, social learning methods were included among the five most effective strategies for the domains of attention (three strategies; items 2, 5, and 9), psychomotor speed (three strategies; items 3, 7, and 12), and memory (two strategies; items 3 and 5) but not for the domain of problem solving.

In the area of problem solving, employment specialists perceived that the most effective strategies for helping clients were those that closely involved the specialist in addressing the issue, which was not the case for the other domains. The strategies were problem solving with the client (item 1), prompting the client on the steps of problem solving (item 6), encouraging the client to call the employment specialist to help solve a problem (item 2), and problem solving with the employer (item 10). It is unclear why employment specialists appear to rely less on social learning methods (and find them less effective) and use more direct intervention to address clients' limitations in problem solving. It is possible that employment specialists find problem solving a more difficult cognitive skill to teach their clients. Alternatively, when it comes to helping a client deal with a problem on the job, there may be a smaller margin of error (perceived or real) and greater time pressure than when addressing difficulties with attention, psychomotor speed, or memory.

In addition to differences between the cognitive domains in the types of coping strategies perceived to be most effective, the study found that employment specialists on average rated strategies for dealing with attention problems as significantly more effective than those for the other cognitive domains. This finding is partially consistent with McGurk and Mueser's ( 7 ) model of cognitive functioning and supported employment, which posits that employment specialists are more able to help clients compensate for and overcome the effects of impairments in basic cognitive functions, such as attention, than in more complex functions, such as memory and problem solving, which rely on intact attentional capacity. However, contrary to the model that posits that employment specialists will have incrementally more difficulty managing impairments in psychomotor speed, memory, and problem solving, effectiveness ratings did not differ significantly between these three domains.

The number of coping strategies employment specialists reported using was significantly correlated with the overall perceived efficacy of the strategies. This finding is consistent with research on coping with symptoms, which has found that overall coping efficacy is higher among people who report using more coping strategies ( 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ). In addition, the number of different coping strategies used by employment specialists was correlated with the percentage of clients on their caseloads who were working, even after the analysis controlled for the educational level of the specialists. There are several possible interpretations of this finding. First, employment specialists who use more strategies to help clients cope may be more effective in diminishing the impact of cognitive impairments on work, leading to higher employment rates. Second, employment specialists who have more clients working for reasons other than their use of cognitive coping strategies may naturally develop more such strategies to support their clients' continued employment. The latter is a distinct possibility, because the survey did not specify a time frame, and thus ratings could be based on specialists' current caseload of working clients.

Third, the number of coping strategies endorsed by employment specialists could reflect efforts other than coping with cognitive impairment that have an impact on work, such as coping strategies for other symptoms, collaborating with employers and significant others, matching clients to jobs based on interests, tapping a broad range of contacts to identify potential job leads, and using motivational enhancement methods, such as motivational interviewing ( 16 ). Greater use of any or all of these strategies could contribute to better employment outcomes, suggesting that employment specialists' experience, effort, resourcefulness, and ingenuity in helping clients pursue their vocational goals is most critical to their success.

This study cannot determine the causal relationship between use of coping strategies for cognitive impairment and work status. However, considering the importance of cognitive functioning as a predictor of employment among persons with severe mental illness ( 5 ), the possibility that use of more coping strategies to help clients manage their cognitive difficulties contributes to better employment outcomes may have important implications for improving supported employment services. Books and training materials on supported employment do not provide a systematic explication of the nature of cognitive impairments in severe mental illness, their impact on work, or strategies for dealing with them ( 17 , 18 ). Enhancing the ability of employment specialists to help their clients cope with cognitive impairments, especially specialists who use fewer strategies, may improve their clients' employment outlook.

Even though many employment specialists' are aware of their clients' cognitive difficulties and employ a wide range of strategies to help them cope more effectively, the question remains as to whether these efforts are sufficient to overcome the effects of severe cognitive impairment on work for all clients. Employment specialists who used coping strategies rated them on average as just below effective, suggesting that there is much room for improvement. Indeed, more focused efforts to remediate cognitive functioning, such as cognitive rehabilitation, may be necessary to improve work outcomes in this subgroup of clients ( 19 ). Research is needed to address this question.

Conclusions

Little is known about whether and how supported employment specialists help their clients cope with cognitive impairments on the job. This study evaluated the strategies used by employment specialists to help clients in supported employment programs manage cognitive impairments that interfered with obtaining and keeping jobs. Employment specialists reported using a wide variety of strategies for helping their clients cope, which they rated on average as just below effective. The number of coping strategies that specialists reported using was significantly correlated with the perceived effectiveness of the strategies and the proportion of clients on their caseloads who were working.

The findings indicated that supported employment specialists were actively involved in helping clients cope with their cognitive impairments and that they perceived their efforts to be helpful. Although specialists who used more coping strategies to help clients manage their cognitive difficulties also had higher rates of working clients on their caseloads, the reasons for these associations are unclear. Further research is needed to evaluate whether employment specialists' use of more strategies to help clients cope with cognitive problems contributes to better work outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Margaret Almeida, R.N., B.C., Ed Baily, M.S., Thomas J. DeRosa, M.S., Michelle DesRoches, L.M.S.W., Sara Kalvin, B.A., Grace Kim, B.S., O.T.R.-L., Richard LaPuglia, M.A., David Loveland, Ph.D., Joan Marder, B.A., Judith Mulder, B.A., and Bill Naughton, M.A.

1. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313-322, 2001Google Scholar

2. Bond GR: Principles of the Individual Placement and Support Model: empirical support. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:11-23, 1998Google Scholar

3. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, et al: Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the "right stuff"? Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:119-136, 2000Google Scholar

4. Mueser KT: Cognitive functioning, social adjustment and long-term outcome in schizophrenia, in Cognition in Schizophrenia: Impairments, Importance, and Treatment Strategies. Edited by Sharma T, Harvey P. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 2000Google Scholar

5. McGurk SR, Mueser KT: Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and work in supported employment: a review and heuristic model. Schizophrenia Research 70:147-174, 2004Google Scholar

6. Gold JM, Goldberg RW, McNary SW, et al: Cognitive correlates of job tenure among patients with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1395-1402, 2002Google Scholar

7. McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Harvey PD, et al: Cognitive and symptom predictors of work outcomes for clients with schizophrenia in supported employment. Psychiatric Services 54:1129-1135, 2003Google Scholar

8. Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC: Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study. New York, Wiley, 1958Google Scholar

9. Dickinson D, Iannone VN, Wilk CM, et al: General and specific cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 55:826-833, 2004Google Scholar

10. Heaton R, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, et al: Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics: relationship to age, chronicity, and dementia. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:469-476, 1994Google Scholar

11. Ericsson KA, Charness N: Expert performance: its structure and acquisition. American Psychologist 49:725-747, 1994Google Scholar

12. Falloon IRH, Talbot RE: Persistent auditory hallucinations: coping mechanisms and implications for management. Psychological Medicine 11:329-339, 1981Google Scholar

13. Mueser KT, Valentiner DP, Agresta J: Coping with negative symptoms of schizophrenia: patient and family perspectives. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:329-339, 1997Google Scholar

14. Tarrier N: An investigation of residual psychotic symptoms in discharged schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 26:141-143, 1987Google Scholar

15. Wahass S, Kent G: Coping with auditory hallucinations: a cross-cultural comparison between Western (British) and Non-Western (Saudi Arabian) patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:664-668, 1997Google Scholar

16. Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

17. Becker DR, Drake RE: A Working Life for People With Severe Mental Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

18. Becker DR, Bond GR: Supported Employment Implementation Resource Kit. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2004Google Scholar

19. McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Pascaris A: Cognitive training and supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: one year results from a randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin 31:898-909, 2005Google Scholar