A Comparison of Competitive Employment Outcomes for the Clubhouse and PACT Models

Adults with serious mental illness have many challenges in attaining and retaining employment. Much of the literature focuses on unemployment rates, with estimates ranging from 67 percent ( 1 ) to 85 percent ( 2 ). This suggests that a majority of adults with mental illness need extra supports to secure and sustain employment. Many studies, which primarily focus on increasing job placement rates, have evaluated the efficacy of vocational rehabilitation models ( 3 ). These studies have been important in beginning the discussion on employment outcomes, but it is crucial that different facets are explored to give a fuller understanding of employment success.

Placement rates do not take into consideration the ability to retain jobs. Supported employment programs vary greatly, and no single definition has come into common usage. Supports can range from assistance with résumé writing to ongoing relationships between program staff and employers. Some supported employment programs can place individuals in jobs rapidly, and if the jobs end prematurely, a person can be placed again. These placements often occur without regard to compatibility, skill, or readiness. A lack of job skills or experience limits the opportunities available to adults with mental illness. Rapid replacement into multiple jobs can lead to elevated employment rates, as an individual is working more days but is moving from job to job. A study following 150 patients entering a vocational rehabilitation trial evaluated the number of hours worked during a 24-month period ( 4 ), but there is no mention of how long research participants were able to remain employed in a specific job. In another study job retention was analyzed indirectly through monthly employment rates ( 5 ). In each case, rapid replacement will give elevated figures that misrepresent the efficacy of the vocational rehabilitation programs.

A potentially more effective way of determining employment success of a program is the average job duration of its clients, because it measures the ability of the client to retain a position. An increase in job duration indicates that clients possess the skills necessary for functioning on a job, such as good hygiene habits; competency in negotiating complex relationships with coworkers, supervisors, and customers; ability to learn job responsibilities; perseverance to stay with a job during difficult situations; and wherewithal to access supports. Evaluation of job duration in combination with job earnings may lead to more informative analyses.

One study analyzed job duration for persons with severe mental illness who were involved with an individual placement and support model and found that the model showed reasonable results ( 6 ). However, in that study, all participants were required to have an interest in obtaining competitive employment, which may have led them to have a longer average job duration than participants in programs that accept applicants regardless of their work interest. A fuller picture of employment outcomes was not forthcoming, because earnings were not addressed.

The purpose of the study presented here was to determine if the clubhouse model has employment placement rates comparable to those in the Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) model, while sustaining members (clients) longer on jobs and maximizing earnings. It is believed that the design of the clubhouse model creates an environment that helps members to be better prepared to succeed in the work environment as defined by these outcomes.

Methods

The experimental research design was a randomized longitudinal study. Fountain House's institutional review board approved the project, and informed consent was obtained from all research participants.

A longitudinal study of the clubhouse and PACT models was conducted as part of the Employment Intervention Demonstration Project ( 7 ). The intention was to compare different modalities of psychiatric rehabilitation, and the focus was primarily on the efficacy of each model in placing consumers in competitive employment.

Settings

The clubhouse model was chosen for the study because it is a widely replicated, well-defined model of psychiatric rehabilitation and community support, but there has been little documentation of its success. Before the International Center for Clubhouse Development (ICCD), a federation of similarly conceived programs, developed a common set of standards to clearly define the parameters of the clubhouse model, the term clubhouse had become diffuse and was used to describe a wide array of programs, which led to a wide variation in the implementation and the quality of the approach. In order to become certified by ICCD, clubhouses regularly submit to a peer-review certification process. Evidence shows that ICCD certification is a valid quality assessment, and clubhouses with ICCD certification significantly outperform those without certification in several areas, including vocational outcomes ( 8 ). More than 100 clubhouses are certified by the ICCD in the United States.

The clubhouse program uses a professional self-help model in which members, along with staff, work together to help individual members achieve their goals. Members voluntarily work within a created environment as well as in the larger community. The environment is based on a network of supportive relationships, which use voluntary work and education as mechanisms for recovery. Members participate in all the work of the clubhouse that is for the benefit of the membership. The work includes cleaning, cooking, research, video production, horticulture, staff evaluation, and tutoring other members in GED preparation and college courses. The clubhouse serves as a base for developing strong relationships and strengthening members' self-esteem. Membership is voluntary and staff assist members with the support needed to succeed. Most members have goals of getting a job, an education, a home, and friends.

The clubhouse model offers a variety of employment options to its members, including transitional, supported, and independent employment. Transitional employment through the clubhouse model allows members to work in integrated settings while getting paid the prevailing wage directly from the employer. The member works for the employer and can be fired by the employer. Distinctions between transitional employment and other forms of supported employment are that in transitional employment the jobs are time limited, the clubhouse covers absences, and the positions are reserved for clubhouse members.

PACT was chosen for the control model in this study because the program has a long-documented record of success in working with adults with serious mental illness ( 9 ) and a recent emphasis on employment. PACT (formerly called Training in Community Living) evolved in Madison, Wisconsin, in the 1970s ( 9 , 10 , 11 ) and has been replicated throughout the United States with successful employment outcomes ( 12 ). The model employs a treatment team involving a variety of professionals that may include psychologists, substance abuse specialists, case managers, nurses, and part-time psychiatrists who work together to coordinate an array of services for its clients, including case management, psychiatry, and counseling. Recently, several PACT teams have added vocational specialists, who assist clients in obtaining supported employment. The team meets with clients in public places, the clients' homes, or the PACT office.

Employment

All employment included in the analyses, including transitional, supported, and independent employment, are defined as competitive employment by the U.S. Department of Labor ( 13 ). Its criteria are pay that is at least minimum wage and a location that is in an integrated setting. Previous analysis has demonstrated that, in addition to complying with this definition, clubhouse-based transitional employment has more in common with jobs not set aside for people with disabilities than with jobs set aside for those with disabilities in the areas of level of integration, days employed, and earnings ( 14 ). Jobs that paid less than minimum wage do not fit this definition and were excluded from the analyses. For the purposes of this study, no distinction was made for the different types of employment included in the analyses.

Design

The five-year longitudinal study was conducted in Worcester, Massachusetts. Genesis Club, an ICCD-certified clubhouse, was the experimental condition, and the PACT model was the control condition. The PACT model had a newly developed team with a vocational component under the supervision of an experienced group, including founders of the model from the original site in Madison, Wisconsin. Data were collected from February 1996 to August 2000.

Study participants

Applicants to the study were referred from several mental health providers in the Worcester area. Of the 465 applicants, 52 (11 percent) objected to being randomly assigned to study groups and 75 (16 percent) were not interested in participating. Of the remaining 338 applicants, 177 met the eligibility requirements (52 percent). After acceptance into the study, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions by picking a card from a hat (89 participants were assigned to the clubhouse model, and 88 were assigned to the PACT model). Initially all participants accepted their assignment. One participant withdrew from the project and requested that all her data be removed from the analyses. Six other participants withdrew from the project within the first week and were removed from the analyses, leaving 170 participants) (clubhouse, 86 participants, and PACT, 84 participants). After 127 weeks, 72 clubhouse and 76 PACT participants remained active in the project (148 of 177 participants, or 84 percent).

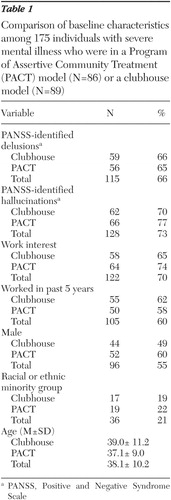

All 177 participants in the study gave informed consent; had diagnoses of bipolar disorder, major depression, or schizophrenia and its related disorders as defined by the DSM-IV ; were aged 18 years or older; did not have severe mental retardation (IQ greater than 60); had not previously participated in either program; and were not competitively employed at time of intake. Interviewers administered the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)—which has been established to have high reliability and validity ( 15 )—to assess positive, negative, and general symptoms. The two interviewers had high rates of interrater reliability on each subscale (positive, r=.95; negative, r=.89; and general, r=.94) and high test-retest reliability (positive, r=.93; negative, r=.95; and general, r=.87) ( 16 ). Immediately after acceptance into the study, as part of the baseline interview, 175 participants completed the PANSS. Participants were not screened for work readiness, interest in work was not a requirement for participation, and work history was collected for 175 participants. There were no significant differences in PANSS-identified symptoms, work indicators, or demographic characteristics between the participants in the two models ( Table 1 ).

|

Procedure

Interviews were conducted at baseline and every six months for 2.5 years by independent interviewers who collected information on service satisfaction, symptoms, social networks, medication, job history, and hospitalizations. Staff at each program tracked all jobs acquired by their participants, many of which were obtained with assistance from the respective agencies. Other employment data were self-reported to program staff or the interviewers. All case management and vocational services provided to study participants were logged by clubhouse and PACT staff. Each participant was followed for 127 weeks or until he or she withdrew from the project. Reasons for withdrawal include moving, death, and refusal to continue to participate in either the condition or the study.

Data analysis

Time-based analyses compared weekly employment and job placement rates for clubhouse and PACT participants, the unit of analysis being participant by week by model. In order to compare participants who entered the study on different dates, calendar dates were transformed to week numbers reflecting the number of weeks that each participant had been enrolled in the study. A binary variable indicated whether each participant was competitively employed in a given week (weekly employment), and a second binary variable indicated whether each participant had been placed in his or her first competitive job in or before a given week (job placement).

Binary employment outcomes were analyzed with generalized estimating equations (GEEs) of the Genmod procedure in SAS with a logit link function. GEEs extend the generalized linear model to deal with potentially correlated data, such as weekly employment levels within participants ( 1 7). An independent working correlation matrix was used to adjust the standard errors of the estimates for within-participant observations that might be correlated over time. Time effects and treatment-by-time interactions were also tested.

A second group of job-based analyses compared average job duration, hours, and wages of PACT and clubhouse participants who attained competitive employment, the unit of analysis being participant by job by program. Job duration was defined as the total number of weeks of competitive employment per job worked by the participant. Hours and wages were similarly defined as total hours worked and total wages earned per job.

Job-based outcomes were once again analyzed with GEEs in SAS Proc Genmod with independent working correlation matrices used to adjust the standard errors for within-participant factors that might be correlated across jobs when participants worked multiple jobs during the course of the study. Gamma error distributions with identity link functions were used to model all job-based outcome data, which were positively skewed, approximating gamma probability density functions. Total number of jobs worked per participant in each treatment condition was also estimated by generalized linear modeling with gamma error distribution and identity link function. Because of the presence of non-normal error distributions in the job outcome data, standard errors may not be symmetric about the mean estimates. Therefore, upper- and lower-confidence intervals were provided in place of standard errors for these analyses.

Spearman rank-order correlations ( 18 ) between job duration, hours, and wages were estimated in order to identify potential covariates in the hours and wages test models. Job duration was entered as a covariate estimating hours, in order to control for potential correlations between job duration and hours, and total hours was entered as a covariate estimating wages, in order to control for any relationship between hours and total wages. Use of these covariates also provided the opportunity to estimate hours per week and hourly wages directly as parameters.

All statistical tests for time-based and job-based analyses were conducted at significance level α =5 percent with all confidence intervals (CIs) estimated at 1- α =95 percent. Significance tests for the job-based outcomes used a type 3 likelihood ratio chi square statistic.

Results

Time-based outcomes

The first test was for differences in job placement rates over time between the PACT and clubhouse models. Week number was also entered as a quadratic term, and interactions between models and week number (time) were tested. No significant differences were found between the two models in job placement rates over the course of the study, and no significant interactions between treatment models and time were observed. At week 127, total job placements in the PACT model remained within the CIs for total job placements in the clubhouse model (56 placements in the PACT model, or 74 percent, CI=57-76 percent, compared with 43 placements in the clubhouse model, or 60 percent, CI=52-74 percent).

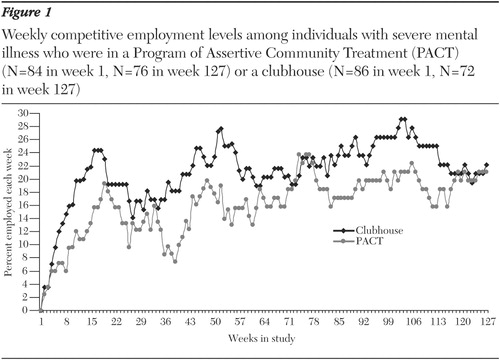

A second GEE tested for differences between PACT and clubhouse in weekly employment rates. Figure 1 provides the weekly employment rates for both models.

Week number was entered as two sequential quadratic terms representing the steep growth in employment rates during the first six months of the study and the slower growth in employment rates over the subsequent two years. No significant differences were found between the two models in weekly employment rates over the course of the study, and no significant interactions between models and time were observed. Overall, weekly employment levels tended to equal or exceed previously published rates of 15 percent to 20 percent for the individual placement and support model ( 5 ).

Job-based outcomes

Four additional tests were conducted for differences in total jobs worked, job duration, hours, and wages for PACT and clubhouse participants who attained competitive employment. No significant differences in total jobs worked were found between the two programs. Because the average participant from both programs worked more than one job over the course of the study (PACT, 2.1, CI=1.8-2.4; clubhouse, 2.2, CI= 1.8-2.5), GEEs were thus used in the analyses of job duration, hours, and wages to adjust the standard errors for within-participant correlations across multiple jobs.

Tests for differences in average job duration found that clubhouse members worked significantly more weeks per job than PACT clients (mean of 21.8 weeks, CI=16.2-27.4, compared with a mean of 13.1 weeks, CI= 9.8-16.4; χ2 =6.37, df=1, p<.01). Correlations between job duration, hours, and wages were then estimated. All three outcomes were significantly correlated for both programs, with job duration showing similar levels of association with hours (PACT, r=.84, df=117, p<.01; clubhouse, r=.90, df=91, p<.01) and wages (PACT, r=.82, df=117, p<.01; clubhouse, r=.90, df=91, p<.01). Hours and wages were strongly associated as well (PACT, r=.99, df=117, p<.01; clubhouse, r=.99, df= 91, p<.01). Job duration was thus entered as a covariate estimating total hours worked, and total hours, in turn, was used as a covariate in the wages model. No significant difference was found for hours worked per week (PACT, mean of 21.7 hours per week, CI=18.9-24.5; clubhouse, mean of 19.7 hours per week, CI= 16.3-23.2). However, clubhouse participants earned significantly higher hourly wages than PACT participants (mean of $7.38 per hour, CI=$6.74-8.02, compared with a mean of $6.30 per hour, CI=$6.03-6.58; χ2 =7.72, df=1, p<.01).

Discussion

Although this study showed that the PACT model achieved job placement rates that were 14 percent higher than those in the clubhouse model, both models demonstrated a high proficiency in placing candidates over an extended period of time. PACT and clubhouse participants maintained 15 percent to 25 percent weekly employment levels, which meet and exceed other published findings ( 5 ). Placement rates and employment levels over time are two indicators of program success that should be considered. However, additional findings indicate that these time-based outcomes should not be considered in isolation from job-based outcomes, such as job duration and wages.

The average participant in both programs was employed in more than two jobs during the study and worked approximately 20 hours a week. However, clubhouse members remained employed an average of two months longer than PACT clients, a significant 66 percent difference in job duration. At 20 hours per week that adds up to an incremental month of full-time employment and an additional $1,200 in earnings at the clubhouse average of $7.38 per hour.

Clubhouses place an emphasis on preparing members for work through the work-ordered day and establishing a community, which provides a network of continual relationships and community support services by members and staff. This may have led to the sustaining of members on jobs for 8.7 more weeks on average. Better preparation and support may also lead to the acquisition of higher-paying jobs. Clubhouse members earned $1.08 per hour more than PACT clients, a significant 17 percent difference in hourly wages.

Conclusions

Previous findings have shown PACT interventions to have high job placement rates ( 12 ), and the analyses presented here found no significant differences between PACT and clubhouse placement rates over a period of 2.5 years. Achieving placement rates consistent with those of PACT for such a long duration is a significant accomplishment for the clubhouse model. Both programs also maintained strong weekly employment levels throughout most of the study.

Previous empirical evaluations have focused primarily on time-based outcomes, such as job placement rates ( 3 , 5 ). However, tracking only placement rates or weekly employment levels neglects to address the full potential of vocational models. No significant differences were found between PACT and clubhouse placement rates or employment levels, yet examination of job-based outcomes, such as wages and job duration, provided valuable insights. Clubhouse participants earned significantly higher hourly wages and stayed employed for significantly more weeks than PACT participants.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by cooperative grant UD7-SM-51831 from the Center for Mental Health Services as part of the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program. The views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of any agencies or collaborators. The authors thank Courtenay Harding, Ph.D., William Eaton, Ph.D., Carla Berkeley, B.A., Thomas Sweet, B.A., and Gary Sokolow, M.F.A., M.B.A., for comments on earlier versions of this article.

1. Mechanic D, Blider S, McAlpine DD: Employing persons with serious mental illness. Health Affairs 21(5):242-253, 2002Google Scholar

2. Milazzo-Sayre LJ, Henderson MJ, Manderscheid RW, et al: Persons treated in specialty mental health care programs, United States, 1997, in Mental Health, United States, 2000. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. DHHS pub no SMA 01-3537. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2001Google Scholar

3. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313-322, 2001Google Scholar

4. Gold JM, Goldberg RW, McNary, et al: Cognitive correlates of job tenure among patients with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1395-1402, 2002Google Scholar

5. Lehman AF, Goldberg R, Dixon L, et al: Improving employment outcomes for persons with severe mental illnesses. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:165-172, 2002Google Scholar

6. Mueser KT, Becker DR, Wolfe R: Supported employment, job preferences, job tenure, and satisfaction. Journal of Mental Health 10:411-417, 2001Google Scholar

7. Cook JA, Carey MA, Razzano LA, et al: The pioneer: the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program. New Directions for Evaluation 94:31-44, 2002Google Scholar

8. Macias C, Barreira P, Alden M, et al: The ICCD benchmarks for clubhouses: a practical approach to quality improvement in psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Services 52:207-213, 2001Google Scholar

9. Dixon L: Assertive community treatment: twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatric Services 51:759-765, 2000Google Scholar

10. Stein LI, Test MA: An alternative to mental health treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Google Scholar

11. Stein LI, Test MA: The training in community living model: a decade of experience. New Directions for Mental Health Services 26:1-98, 1985Google Scholar

12. Becker RE, Meisler N, Stormer G, et al: Employment outcomes for clients with severe mental illness in a PACT model replication. Psychiatric Services 50:104-106, 1999Google Scholar

13. Department of Labor: Job Training Program Act, disability grant program funded under title III, section 323 and title IV, part D, section 452. Federal Register 63:60, 1998Google Scholar

14. Johnsen M., McKay C, Henry AD, et al: What does competitive employment mean? A secondary analysis of employment approaches in the Massachusetts Employment Intervention Demonstration Project, in Research on Employment for Persons With Severe Mental Illness: Research in Community and Mental Health, Vol 13. Edited by Fisher W. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 2004Google Scholar

15. Bell M, Millstein R, Beam-Goulet J, et al: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: reliability, comparability, and predictive validity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:723-728, 1992Google Scholar

16. Trumbetta S, McHugo GJ, Drake RE: EIDP Study Interview Reliability Report. Concord, NH, Dartmouth University, 1997Google Scholar

17. Hu FB, Goldberg J, Hedeker D, et al: Comparison of population-averaged and subject-specific approaches for analyzing repeated binary outcomes. American Journal of Epidemiology 147:694-703, 1998Google Scholar

18. Artusi R, Verderio P, Marubini E: Bravais-Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients: meaning, test of hypothesis, and confidence interval. International Journal of Biological Markers 17:148-151, 2002Google Scholar