Use of PASRR Programs to Assess Serious Mental Illness and Service Access in Nursing Homes

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed the implementation of state Preadmission Screening and Resident Review (PASRR) programs with respect to identification of serious mental illness among nursing facility applicants and residents and access to mental health services. METHODS: A national survey was conducted with representatives from agencies that implement PASRR in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Also, 44 states sent PASRR data for review. Four states were selected for an in-depth study; six nursing homes per state were selected and one staff member from each facility was interviewed (N=24). Medical records were reviewed for 30 to 40 residents from each facility who met criteria for potentially having a disabling serious mental illness (N=786). RESULTS: Medical records showed that 50 percent of patients at the time of admission and 68 percent of patients at the time of the record review had a psychiatric diagnosis, typically a diagnosis of depressive disorder. At the time of admission, fewer records identified individuals with a serious mental illness (9 to 20 percent) or a primary diagnosis of any psychiatric illness (5 to 12 percent). Many records indicated that in-depth, required PASRR screens were not performed. Ninety percent of the states reported that Medicaid covers only basic psychiatric consultation services, such as medication monitoring, in nursing facilities. Between 30 and 32 percent of national survey respondents also characterized access to facilities that provide mental health services as limited and of variable quality. Although all 24 nursing facilities reported providing psychiatric consultation services, access to other mental health services, such as psychosocial rehabilitation or individual counseling, varied considerably. CONCLUSIONS: Nursing facility compliance with administration and documentation of PASRR screens appears problematic. Nevertheless, there do not appear to be excessively high numbers of residents with serious mental illness, suggesting that state PASRR programs may contribute positively to the identification of people with serious mental illness. However, many nursing facility residents have some type of psychiatric illness, and PASRR legislation does not appear to have enhanced their ability to gain access to mental health services beyond standard psychiatric consultation and medication therapy.

Under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1987, Congress created a Preadmission Screening and Resident Review program, now referred to as PASRR, to address concerns that many people with serious mental illness and mental retardation were living in nursing facilities that lacked adequate resources to care appropriately for them. At the time, some states used nursing facility placements as a cost-effective means of downsizing psychiatric institutions (1,2,3).

PASRR legislation required state Medicaid agencies to establish programs to screen and identify nursing facility applicants and residents for serious mental illnesses. PASRR legislation also required screening to evaluate whether a nursing facility is the appropriate place for a patient to receive care and to determine need for specialized services to treat mental illness. PASRR involves two parts: preadmission level I and level II screens and level II resident reviews. [A table with an overview of the PASRR program is available in the online version of this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org.] Originally, states were required to conduct resident reviews on an annual basis, but under the Balanced Budget Amendment of 1996, the requirement for annual resident review was eliminated and replaced with a requirement to screen when "there is a significant change in physical or mental condition."

More than 15 years after PASRR legislation was created, mass transinstitutionalization of people from psychiatric institutions to nursing facilities has not occurred (4). Nevertheless, studies suggest that nursing facilities are increasingly serving residents with a wide range of mental disorders, most commonly depression and dementia (4,5,6). Furthermore, many nursing facility residents do not receive appropriate mental health services and might be better served in alternative community settings (7,8,9).

Such reports shed light on the broader issues that congress intended PASRR to address. Yet the specific effect of PASRR legislation remains unclear and difficult to evaluate. Only two investigations have attempted to examine PASRR programs more directly. In 1996 a national survey conducted by the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law found tremendous variation between states in the implementation of PASRR programs and the availability of mental health services in nursing facilities. More recently, the U.S. Health and Human Services' Office of the Inspector General investigated state PASRR programs, focusing on younger Medicaid beneficiaries with serious mental illness who were residing in nursing facilities (9). The Office of the Inspector General found significant levels of noncompliance among nursing facilities, particularly in mental health assessment, and inadequate federal and state oversight. These studies suggest that states may not be implementing PASRR programs effectively, potentially limiting the ability of these programs to assist individuals with serious mental illness in nursing facilities.

To further investigate the effectiveness of implementing PASRR programs, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), in collaboration with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), funded a two-phase investigation of PASRR programs. Phase I involved a comprehensive literature and legislative review of PASRR programs (10). Phase II involved a national survey of PASRR oversight agencies followed by exploratory case studies in four states. Case studies included medical record reviews and key informant interviews with nursing facility staff, which are discussed in this article, along with clinical interviews of residents of nursing facilities, which are not presented in this analysis (11). In this article we present selected findings from phase II on the effectiveness of PASRR implementation, particularly as it relates to identification of mental illness among nursing facility residents and access to specialized and other mental health services.

Methods

A national survey was conducted in 50 states and the District of Columbia, augmented by case studies in four states. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from multiple data sources by using several data collection tools. Study methods, protocols, and consent forms were reviewed and approved by the White House Office of Management and Budget before conducting the research.

National survey of PASRR agencies

From June to October 2002, interviews were conducted with representatives from agencies that implemented PASRR in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, yielding a response rate of 100 percent. In total, interviews were conducted with 47 state mental health authorities, 43 state Medicaid agencies, and five state aging or health agencies. Most interviews were conducted by telephone; however, written responses were also accepted. To protect anonymity, we collectively refer to all national survey respondents as "states," including Washington, D.C., when presenting results.

Structured interview protocols were developed by using a core set of closed- and open-ended questions about PASRR screening procedures, outcomes, and mental health service delivery in nursing facilities. Items specific to Medicaid, mental health authorities, and other state agencies were developed to tailor interviews. In addition, a standard data and document request form was used to collect PASRR program documents and screening statistics from the most recent fiscal year (2001 or 2002). Forty-four states (86 percent) submitted documents.

Follow-up case studies in four states

To augment national survey findings with nursing facility perspectives, four states were selected for an in-depth study. From these four states, a sample of 24 nursing facilities (six per state) was selected. Data collection involved an interview with a staff member from each of the 24 facilities and reviews of the medical records of 30 to 40 nursing facility residents per facility who met criteria for potentially having a disabling serious mental illness.

Sampling

State selection. National survey findings indicated that the greatest source of variation in PASRR implementation was the type of entity designated by states to conduct level II screens. Four types were identified: private mental health agencies, public mental health agencies, individual mental health practitioners, and independent state agencies. States were categorized by these four screener types and by geographic region (South, West, Midwest, and Northeast). One state per type in each geographic region was selected.

Nursing facility selection. SAMHSA identified geographic variability (urban and rural) and facility size as important nursing facility stratification criteria. The 2000 census was used to select the largest metropolitan statistical area and a noncontiguous rural county in each state. Within each urban and rural county, a random sample of three nursing facilities, stratified by facility size (small, 60 beds or fewer; medium, 61 to 90 beds; and large, more than 90 beds), was drawn by using the CMS Nursing Home Compare database.

Nursing facility resident medical record selection. Three criteria were used to identify residents who might have disabling serious mental illness (for example, psychotic or bipolar disorders): presence of PASRR level II screen, current prescription of psychotropic medications (for example, neuroleptics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and mood stabilizers), or any psychiatric diagnosis, excluding dementia but not limited to serious mental illness. Residents who met any of these three criteria were compiled in a master list, from which up to 40 residents from each nursing facility were randomly sampled. No individual-identifying data were abstracted from records.

Data collection procedures and tools

State recruitment. Invitation letters were mailed to PASRR program administrators in the four selected states. All four agreed to participate. After the nursing facility sample was drawn, letters were mailed to selected nursing facilities inviting their voluntary participation. Follow-up telephone calls were also made to answer questions and secure participation. On average, two nursing facilities per state declined to participate, most often citing time and staffing constraints. After facilities declined, the sample was redrawn according to the criteria described earlier. Data collection in each of the four selected states was completed from May to July 2003.

Key informant interviews. A total of 24 key informant interviews were conducted with nursing facility staff from six nursing facilities in four states. Informants were identified by facility administrators as responsible for implementing PASRR procedures. A structured interview protocol, similar to the national surveys, was developed.

Medical record abstractions. In six nursing facilities in all four states, residents' medical records were abstracted for 30 to 40 nursing facility residents per facility who met criteria for potentially having a disabling serious mental illness. Records were reviewed for 786 residents. Key information was abstracted on residents' background characteristics, medical and psychiatric history, psychotropic medications prescribed, and mental health services received for two points in time: initial admission and the current review period (May through June 2003). Trained mental health and medical record professionals performed abstractions.

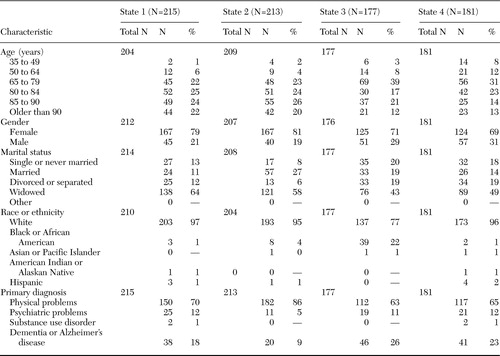

Nursing facility resident characteristics. Table 1 displays characteristics at the time of admission of the nursing facility residents sampled. In all states, most residents sampled were older than 65 years, female, and Caucasian. Primary diagnoses for a majority of residents indicated a physical illness at initial admission, as opposed to a psychiatric or dementia-related illness. In three of four states, 11 or 12 percent of residents had a primary diagnosis of psychiatric illness upon admission.

Results

National survey and case study results were integrated to assess the effectiveness of the implementation of PASRR programs with respect to the identification of mental illness, particularly key diagnoses of serious mental illness, among nursing facility residents and applicants and to the ability to gain access to specialized and other mental health services among nursing facility residents.

Overall PASRR screening outcomes

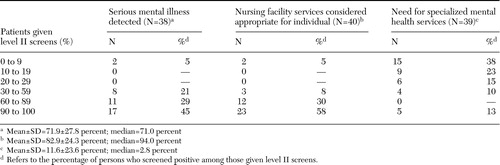

Forty-four states provided annual data on outcomes of preadmission level II screens administered to individuals with positive level I screens for potential serious mental illness (Table 2). Results varied widely, most likely reflecting state-by-state differences in PASRR screening processes and tools. Because federal regulations allow considerable latitude in defining serious mental illness and specialized mental health services, states vary in the stringency of their screening criteria for these outcomes. Nevertheless, 45 percent of the states reported that more than 90 percent of patients with positive level I screens were given a diagnosis of serious mental illness, 58 percent reported that for 90 percent of the patients, a nursing facility was the appropriate place to receive care, and 38 percent found that fewer than 10 percent of the patients screened required specialized services. Findings suggest that PASRR level I screens are sensitive to detecting serious mental illness and are consistent with other studies reporting average diversion rates (percentage of patients for whom a nursing facility was the inappropriate place to receive care) of fewer than 10 percent (12,13). In addition, our findings indicated that states most frequently reported that fewer than 10 percent of nursing facility applicants need specialized services, which is consistent with studies from the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, which found that an average of 7.5 percent of nursing facility applicants need specialized services (13).

Identification of serious mental illness

Psychiatric diagnoses at admission. PASRR regulations specify that any mental disorder, excluding dementia-related disorders, can be considered to be a serious mental illness if it leads to a chronic disability. Rather than creating a list of diagnoses considered to be "serious mental illness," PASRR regulations highlight level of functioning as the central criterion to be used in determining who has a serious mental illness. In our reviews of the 786 records of the nursing facility residents, we did not routinely find data on level of impairment associated with a particular psychiatric diagnosis. Furthermore, we did not record individual-identifying information and could not link specific resident charts with Minimum Data Set (MDS) data. Therefore, to generate a more conservative estimate of serious mental illness, we limited our analysis to those diagnoses considered most disabling and most frequently associated with serious mental illness, specifically schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder (14). We excluded other diagnoses often associated with serious mental illness (for example, severe depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder), because there is greater variation in level of functioning associated with these illnesses.

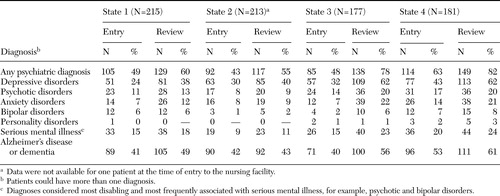

As shown in Table 3, at admission the percentage of residents given a diagnosis of psychotic disorder ranged from 8 to 17 percent, and the percentage given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder ranged from 1 to 7 percent. Although our case study is limited to four states and targets residents likely to have serious mental illness, these findings are comparable to recent national estimates that found that 6 to 8 percent of nursing facility residents have schizophrenia and related disorders (14,15). Sampled nursing facilities did not appear to be admitting excessively high numbers of individuals with these key diagnoses of serious mental illness. Nevertheless, many nursing home residents have psychiatric disorders that may or may not rise to the level of serious mental illness, as defined by PASRR guidelines, which rely on assessment of functional impairment. For example, 24 to 43 percent of residents in our sample were given a diagnosis of some type of depressive disorder (for example, major or minor depression or dysthymia), which is consistent with estimates of depressive disorders in nursing facilities ranging from 12 to 44 percent (4,6). In addition, in our sample of residents, psychiatric diagnoses, particularly depressive disorders, increased from the time of admission to the time that we reviewed the medical records.

Chi square analyses across the four states sampled in our study were performed to examine differences between younger (younger than 65 years) and older (65 years and older) residents on psychiatric diagnoses upon admission. Consistent with the findings of Phillips and Spry (15), our findings showed that younger nursing facility residents were more likely to be given a diagnosis of any psychiatric illness (χ2=4.99, df=1, p<.05), most often psychotic disorder (χ2=15.74, df=1, p<.001) and bipolar disorder (χ2=5.61, df=1, p<.05). No significant age-related differences were found for other psychiatric diagnoses.

Evidence of preadmission level II screens. Residents' charts were reviewed for evidence that all individuals with primary psychiatric diagnoses upon admission received preadmission level II screens as required by regulations. Actual numbers and percentages of individuals who received such screens in our sample were as follows: state 1 (15 individuals, or 60 percent), state 2 (three individuals, or 27 percent), state 3 (no individuals), and state 4 (two individuals, or 10 percent). Consistent with findings from the Office of the Inspector General (9), our findings showed considerable variation in the administrative and documentation process for level II screens across the four states.

Evidence of level II assessments after a change in condition. PASRR regulations require nursing facilities to initiate level II screens when residents experience a "significant change in their physical or mental condition." The original law required annual reassessment; the Balanced Budget Amendment of 1996 reduced that requirement. Although psychiatric diagnoses of residents increased over time in the nursing facilities sampled, more than two-fifths of states (14 of 32 states, or 44 percent) reported that fewer than 100 assessments were conducted in the past year as a result of a significant change in the patient's physical or mental condition (fiscal year 2001 or 2002). In addition, in the medical records reviewed for 786 nursing home residents in all four states, very few assessments were conducted as a result of a significant change in the patient's condition (22 assessments, or 10.3 percent, in one state; zero to two assessments, or 0 to 1.2 percent, in the other three states). This finding is consistent with the findings of the Office of the Inspector General, which found that these types of assessments rarely occur (9).

Access to specialized and other mental health services

Definition and provision of specialized services. Federal regulations allow states flexibility in defining what constitutes specialized mental health services. A majority of states (38 states, or 75 percent) use the most restrictive definition of 24-hour intensive care—that is, inpatient psychiatric care. The others define specialized services more broadly to include services such as psychiatric consultation, psychosocial rehabilitation, and crisis intervention. These services are funded with a variety of sources in nursing facilities, including state general funds, Medicaid rehabilitation option, and requiring that the nursing facility per diem rate cover certain specialized services—for example, medication management.

Provision of lesser-intensity mental health services by nursing facilities. Federal statute requires nursing facilities to provide mental health services (of a lesser intensity than specialized services) to residents with serious mental illness. Thirty-eight of 42 responding states (90 percent) indicated that Medicaid pays for only basic mental health services provided in the nursing facility benefit, most commonly case consultation—for example, visits with mental health professionals, typically to obtain guidance on diagnostic and treatment-related questions—and medication monitoring. Fewer than half of state Medicaid plans cover more comprehensive services, such as intensive case management and psychosocial rehabilitation (18 of 42 states, or 43 percent). Furthermore, at the national survey level, 22 of 37 state Medicaid respondents (59 percent) and 20 of 37 state mental health authority respondents (54 percent) most frequently characterized access to mental health care as either being insufficient or varying considerably from facility to facility.

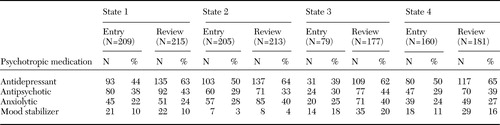

Prescription of psychotropic medications. As shown in Table 4, across all four states, between 39 and 50 percent of the 786 residents were given prescriptions for antidepressants upon initial admission, and the percentage of residents who received such a prescription increased to between 62 and 65 percent by the time of the record review. The mean±SD length of time between initial admission and the record review was 2.6±.3 years (range of 2.2 to 2.9 years). In addition, significant percentages of residents were given prescriptions for antipsychotics or anxiolytics at the time of initial admission (ranging from 22 to 38 percent) and at the time of the record review (ranging from 24 to 44 percent). These data are consistent with other published reports that indicated high levels of prescription of psychotropic medications in nursing homes (16,17).

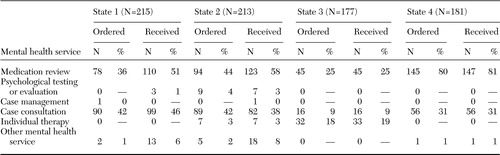

Mental health services ordered and received. Regardless of psychiatric diagnosis, across the four states, orders for mental health treatment during the 30 days before the record review most commonly involved psychotropic medication management and case consultation with mental health professionals. However, because of our 30-day time frame, data were likely skewed to ongoing treatment modalities, such as medication management or individual therapy, rather than services typically rendered upon admission, such as comprehensive psychiatric evaluations. Nevertheless, only one state routinely provided residents with individual therapy. Evidence in progress notes showed that mental health services that were ordered were actually received (Table 5). In fact, in all four states, more services were received than ordered in at least one service category. However, this finding may speak more to the quality of record keeping rather than any systematic effort on the part of nursing facilities to provide additional services.

Challenges faced by nursing facilities in treating individuals with mental illness. A range of 33 to 83 percent of nursing facility staff in all four states most often highlighted difficult behaviors—for example, aggressive outbursts and suicidality—as the most challenging aspect of treating residents with mental illness. Between 33 and 50 percent of the staff surveyed also cited lack of resources to provide or obtain mental health services and understaffing. Furthermore, across all four states, although 100 percent of the staff surveyed reported contracting with a range of mental health professionals—for example, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers—in three states, about half of nursing facilities reported that there was a reluctance among these professionals to serve nursing facility residents.

Discussion

This study integrates findings from a national survey of PASRR agencies and case studies from four states. These results are essentially descriptive and help to clarify how PASRR is being implemented at state and local levels. Although national survey results can be considered to be comprehensive, case study findings should be considered to be exploratory and cannot be generalized to all nursing facilities or nursing facility residents. Nevertheless, these data provide insight into how some nursing facilities implement PASRR and present a snapshot of mental health issues among nursing facility residents.

Study data indicate that the nursing facilities in our sample are not admitting excessively high numbers of individuals at any age with key diagnoses of serious mental illnesses, such as psychotic and bipolar disorders. These results are consistent with early simulation projections by Freiman and colleagues (18) and more current trends reported by Mechanic and McAlpine (4). State PASRR programs appear to effectively identify individuals with serious mental illness, although rates of identification may vary across states, particularly because compliance with PASRR administration and documentation remains problematic, as noted by the Office of the Inspector General (9). Averaged across the four study states, 50 percent of the records assessed at the time of admission and 68 percent of the records assessed at the time of record review indicated some type of psychiatric diagnosis, primarily depressive disorders. Fewer records identified individuals with serious mental illness (9 to 20 percent) or primary diagnoses of any psychiatric illness (12 percent or less) at admission. It is likely that most nursing facility applicants in our sample met functional impairment criteria, with primary diagnoses of physical or dementia-related illnesses (87 to 95 percent) making up a vast majority of admission diagnoses (18).

Considerable variability existed across the four states in our study in the documentation of level II screens in records of individuals with primary diagnoses of psychiatric illness, suggesting some degree of noncompliance with PASRR regulations. Furthermore, as observed by the Office of the Inspector General (9), PASRR assessments that resulted from a significant change in the patient's physical or mental condition were performed infrequently. Our data indicated increased psychiatric diagnoses over time, particularly for depressive disorders. In part, this increase may be due to inadequate documentation or diagnosis of psychiatric disorders upon admission. However, research suggests that depressive symptoms increase with age (14). Regardless, assessments that result from a significant change in the patient's physical or mental condition are critical to ensuring that residents with serious mental illness continue to be identified and receive appropriate mental health treatment.

Given the prevalence of mental disorders in the nursing facilities studied, PASRR may be less effective in enhancing the capacity of nursing facilities to deliver mental health services. In 38 of 42 states, the Medicaid nursing facility benefit covers only basic mental health services, such as medication monitoring and individual counseling; few cover more intensive psychosocial rehabilitation services. Furthermore, almost a third of state respondents in the national survey characterized nursing facility residents' access to mental health services as limited and of variable quality. One respondent highlighted Medicaid as a barrier to mental health service delivery in nursing facilities, stating, "Our Medicaid agency has very strict rules. If the person is in a nursing facility, Medicaid won't pay for any additional [mental health] services outside of [those included in] the per diem. Community mental health centers don't get paid for any services they provide for nursing facility residents."

Limited availability of mental health specialists willing to deliver care in nursing facilities may also affect access to and quality of mental health care. In three of the four states sampled, about half the staff members from the nursing facilities said that they had experienced this problem. For example, one staff member explained, "None are happy to come …. They hesitate to leave their offices and sometimes perceive that they cannot change older people." In addition, although we focused on Medicaid as the primary financing strategy for long-term care of residents of nursing facilities, it is worth noting that Medicare can be the primary payer for psychiatrists, psychologists, and clinical social workers to provide short-term mental health services in nursing facilities. This funding strategy may create disincentives for the development of longer-term treatment models and for other mental health providers to develop expertise in working with this population.

Finally, study findings demonstrate that the PASRR process does not ensure that nursing facility residents receive mental health services. Although all 24 nursing facilities studied provided access to medication monitoring and case consultation services, the availability varied for other mental health services, such as psychosocial rehabilitation and individual counseling. Only 20 percent of facilities offered performance quality review and care team meetings for mental illness treatment, and most (62 percent) indicated that treating persons with mental illness is challenging, primarily because of behavioral issues, and cited a lack of staff and other resources, including mental health professionals willing to provide services to nursing facility residents. These data are consistent with the findings of Shea and colleagues (19) who examined mental health service delivery in nursing homes after the 1987 OBRA; their results showed low levels of mental health treatment and high unmet need for psychosocial services.

Conclusions

The past two decades have brought tremendous expansion of community-based mental health services for individuals with serious mental illness, fueled partly by the development of evidence-based services, such as assertive community treatment, which provide innovative treatment and cost savings (20). Within this broader context, the specific contributions of PASRR legislation in helping to reduce the inappropriate placement of individuals with serious mental illness in nursing facilities remain difficult to evaluate. Nevertheless, our data suggest that the legislation likely has played a positive role in helping to identify nursing facility applicants and residents with serious mental illness.

However, the legislation appears not to have enhanced the capacity of nursing facilities to deliver mental health services beyond standard case consultation and medication therapy. As noted in the Surgeon General's report (14), before and after the passage of PASRR programs, "Medicaid policies discourage nursing homes from providing specialized mental health services, and Medicaid reimbursements for nursing home patients have been too low to provide a strong incentive for participation by highly trained mental health providers." The high prevalence of mental disorders among nursing facility residents studied indicates a continued need for policies and financing strategies to enhance the availability and integration of appropriate mental health services in nursing facilities, especially those with demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of depression, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (21). Enhancing the ability to gain access to appropriate treatment is particularly important given the deleterious interaction of mental illnesses and physical health (22).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jan Earle, B.A., and Dan Timmel, M.S.W., for assistance in the development of this report. The report was prepared by the Lewin Group for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration under purchase order number 03-M00029-50.

Dr. Linkins is affiliated with the Lewin Group, 3130 Fairview Park Drive, Suite 800, Falls Church, Virginia 22042 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Lucca and Mr. Housman were affiliated with the Lewin Group during completion of this assessment. Ms. Smith is with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in Rockville, Maryland.

|

Table 1. Characteristics at the time of admission of 786 nursing facility residents in four states who met criteria for potentially having a disabling serious mental illness

|

Table 2. Data from 44 states that provided data on preadmission level II screening outcomes

|

Table 3. Psychiatric diagnoses of 786 nursing facility residents who met criteria for potentially having a disabling serious mental illness, at entry to the nursing facility or at the time of record review

|

Table 4. Psychotropic medications prescribed at time of entry to the nursing facility or at the time of record review among 786 nursing facility residents who met criteria for potentially having a disabling serious mental illness

|

Table 5. Mental health services ordered and received among 786 nursing facility residents who met criteria for potentially having a disabling serious mental illness

1. Emerson Lombardo N: Barriers to Mental Health Services for Nursing Home Residents. Washington, DC, American Association of Retired Persons, Public Policy Institute, 1994Google Scholar

2. Elderly Remain in Need of Mental Health Services. Washington, DC, US General Accounting Office, 1982Google Scholar

3. Improving the Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, Institute of Medicine, Committee on Nursing Home Regulation, 1986Google Scholar

4. Mechanic D, McAlpine DD: Use of nursing homes in the care of persons with severe mental illness:1985 to 1995. Psychiatric Services 51:354-358,2000Google Scholar

5. Cohen CI, Hyland K, Kimhy D: The utility of mandatory depression screening of dementia patients in nursing homes. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:2012–2017,2003Link, Google Scholar

6. Teresi J, Abrams R, Homse D, et al: Prevalence of depression and depression recognition in nursing homes. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:613–620,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Snowden M, Piacitelli J, Koepsell T: Compliance with PASRR Recommendations for Medicaid recipients in nursing homes. Journal of American Geriatrics Society 46:1132–1136,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bartels SJ, Miles KM, Dums AR, et al: Are nursing homes appropriate for older adults with severe mental illness? Conflicting consumer and clinician views and implications for the Olmstead decision. Journal of American Geriatrics Society 51:1571–1579,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Younger Nursing Facility Residents With Mental Illness: Pre-Admission Screening and Resident Review (PASRR) Implementation and Oversight. Pub no OEI-05-99-00700. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General, 2001Google Scholar

10. Linkins K, Robinson G, Karp J, et al: Screening for Mental Illness in Nursing Facility Applicants: Understanding Federal Requirements. SAMHSA pub no SMA-01-3543. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2001Google Scholar

11. Linkins K, Lucca A, Housman M: Pre-Admission Screening and Resident Review (PASRR) and mental health services for persons in nursing facilities. DHHS pub no SMA-05-4039, Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005Google Scholar

12. PASRR Task Force Report. Chicago, Ill, Society for Social Work Leadership in Health Care, 1995Google Scholar

13. Mental Disability Law and the Elderly: The Impact of PASRR. Washington, DC, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, 1996Google Scholar

14. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

15. Phillips CD, Spry KM: Characteristics and care of US nursing home residents with a history of chronic mental illness. Canadian Journal on Aging 19(suppl 2):1–17,2000Google Scholar

16. Furniss L, Craig SK, Burns A: Medication use in nursing homes for elderly people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13:433–439,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Llorente MD, Olsen EJ, Leyva O, et al: Use of antipsychotic drugs in nursing homes: current compliance with OBRA regulations. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48:198–201,1998Google Scholar

18. Freiman MP, Arons BS, Goldman HH, et al: Nursing home reform and the mentally ill. Health Affairs 9(4):47–60,1990Google Scholar

19. Shea DG, Russo PA, Smyer MA: Use of mental health services by persons with a mental illness in nursing facilities: initial impacts of OBRA '87. Journal of Aging and Health 12:560–578,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 52:45–50,2001Link, Google Scholar

21. Bartels SJ, Levine KJ, Shea D: Community-based long-term care for older persons with severe and persistent mental illness in an era of managed care. Psychiatric Services 50:1189–1197,1999Link, Google Scholar

22. Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al: Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older: a 4-year prospective study. JAMA 277:1618–1623,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar