A Meta-Analysis of Labor Supply Effects of Interventions for Major Depressive Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aims of this study were to examine labor supply effects of interventions for major depressive disorder and to compare these effects with a summary measure of clinical effectiveness. METHODS: Research articles published in English-language journals from 1980 through May 2004 were searched by using five research databases. Only randomized trials that included a placebo group or a usual care group were eligible for the study, regardless of the specific type of intervention. Valid trials were those that enrolled adult patients with major depressive disorder and assessed changes in labor output by using a measure of time worked or labor market participation. From a total of 706 trials uncovered from the database searches, only four met all inclusion criteria. Trial outcomes were transformed into standardized effect sizes on the basis of Cohen's d. Hierarchical linear models were used to separately pool work outcomes and clinical outcomes. RESULTS: An improvement of .34 standard deviation was found in the size of the clinical effect of interventions compared with placebo or usual care among 1,261 unique patients with depression. An improvement of .12 standard deviation was found in the size of the effect on labor supply among 1,848 unique patients. CONCLUSIONS: Although the interventions studied were associated with reduced symptoms of depression and increased labor output, the labor benefits were small according to standard benchmarks used in interpreting the substantive significance of values of Cohen's d. The difference in effects may have been due to different underlying efficacies, brief durations of follow-up, or extrinsic factors that affect labor supply.

Mental disorders can be very disruptive to labor market activities. They reduce the likelihood that affected individuals will be able to participate in the labor market, increase the time absent from work, and lower workplace performance, all of which may result in reduced earnings (1,2,3). Realizing the potential productivity gains from expanding access to appropriate mental health care has long been a goal of policy makers and of advocates for people with mental disorders (4). President Kennedy, in his message on mental illness in 1963, emphasized the labor market benefits from effectively treating and preventing mental disorders (5).

The lost productivity resulting from mental illness in the United States was estimated at more than $200 billion in 1994 (6). At the same time, advances in the clinical sciences have provided clinicians with effective treatments for nearly every major mental illness (7). However, only a small fraction of people with a mental disorder receives appropriate levels of treatment for their condition (8). Together, these observations suggest that by expanding access to evidence-based treatments, the American economy might realize substantial gains in productivity.

But for this supposition to be true, the following complex sequence of conditions must be satisfied: individuals experiencing diminished productivity due to a mental illness must obtain treatment, available treatments must not only reduce symptoms but also improve work-related outcomes, and treatment delivered in community-based settings must be effective—and patients must respond. In this article we focus on the second assumption—that available treatments reduce symptoms of depression and improve work-related outcomes.

Researchers have investigated the impact of interventions for depression on labor supply in several ways: in observational studies (9,10,11), in randomized trials (12,13,14,15), and by using quasi-experimental designs (16). Conclusions arising from observational studies, although applicable to broad populations, are vulnerable to confounding and selection biases. Randomized studies minimize these threats to internal validity but are restricted to selected and possibly unrepresentative populations. In addition, such studies might not reflect the level of care received in community settings. To our knowledge, no meta-analyses have assessed the labor supply effects of interventions for depression by using studies with experimental designs.

A review by Mintz and colleagues (17) that examined mostly randomized trials compared changes in work impairment across a variety of treatments, including tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and psychotherapy. Although the authors found medium to large effects on work functioning, their results were not pooled. In addition, although work functioning scales are used frequently in psychiatric clinical trials, they do not provide a measure of the economic value of work effort that is most useful to policy makers (18). Measuring the economic impact of depression interventions in terms of labor output, such as hours worked, days worked, and changes in employment rates, is a more objective alternative.

In this article we examine two specific questions about the short-term response of labor supply to interventions for major depression. First, on the basis of evidence from randomized controlled trials, do indicators of labor market activity respond to interventions for depression? Second, how does the size of the effect on labor supply compare with the magnitude of the change in symptom severity? The answers to these questions offer an important empirical link in the causal chain relating the social costs of illness to the gains from treatment.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched the medical literature for studies published between January 1980 and May 2004 to identify all randomized controlled trials published in English-language journals that measured the effectiveness of interventions for major depressive disorder in terms of labor supply. Search terms included "depression or depressive disorder," "employment," "work productivity," "work functioning," and "quality of life." MEDLINE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PsycINFO, the Science Citation Index, and the Social Science Citation Index were used. We included studies that enrolled patients with major depressive disorder, were randomized controlled trials, and reported economic outcomes on the basis of time missed from work or employment status. We excluded studies that restricted enrollment to depressed elderly or pediatric populations, that assessed depression among patients with a significant comorbid medical condition (for example, AIDS or cancer), and that focused primarily on patients with a diagnosis of a severe mental illness, such as bipolar disorder, psychoses, or schizophrenia.

Data abstraction

Data were abstracted by using a standardized protocol and were entered electronically into an Excel database. Relevant data elements were abstracted by one reviewer (the first author), and validated by another (the second author). Discrepancies were reconciled through discussion and review of the original article. Study characteristics collected included author, publication year, type of intervention, type of labor output and depression outcome measured, duration of follow-up, percentage of study participants with major depression, mean age, race, gender, and educational attainment. We selected any intervention that involved pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, enhanced access to specialty care, or any combination of these. Control groups consisted of either usual care or no care—for example, placebo.

We abstracted results for two types of outcomes: labor output and clinical response to treatment. Labor outputs were restricted to those measuring time missed from work or participation in the labor market. Data on changes in symptoms of depression were sought for all trials that reported valid measures of labor supply, which often required retrieval of a companion article. Acceptable outcomes were either measures of change in depression status or the percentage of patients responding to the intervention. Response was defined as an improvement of at least 50 percent from baseline values on any of the following symptom scales: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Clinical Global Impression of Severity of Illness (CGI-S), the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D), the Inventory of Depressive Symptomology (IDS), the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), or the 20-item Symptom Checklist (SCL-20). For studies that reported both crude estimates of intervention effects and those adjusted for potential confounders, we selected the adjusted results.

Statistical analysis

Because there was no single measure of treatment effect that was common to all studies, we transformed all outcomes to a common scale, Cohen's d (19), which measures the strength of the intervention relative to a control condition in standardized score units. A Cohen's d of .20, representing a small effect size according to published benchmarks, indicates that the means differ by .2 of a standard deviation, or, equivalently, 1 percent of the variance in the outcomes is explained by treatment group assignment. When any of the required information for computing Cohen's d was absent, it was still possible to calculate effect sizes if a study reported a T or F statistic, corresponding to a statistical test of a difference between group means. Cohen's d can be computed from these test statistics on the basis of published formulae (20). For studies reporting binary indicators of labor market participation, similar formulae were used to calculate Cohen's d.

Assuming heterogeneity in the underlying effect of interventions across studies, we used a Bayesian hierarchical linear model with a random effect specification to pool information (21,22). This approach contrasts with traditional meta-regression analyses, which initially test for a heterogeneous treatment effect. Our approach estimated the between-study variance by using the pooled data to estimate the distribution of the overall treatment effect. Meta-analyses were conducted separately for the labor supply effects and the clinical outcomes.

Model parameters were estimated with use of Bayesian Inference Using Gibbs Sampling (WinBUGS) software (23). WinBUGS uses Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods to generate empirical distributions for the parameters of interest through repeated application of Bayes formula, using the raw effect estimates from each study and user-specified prior distributions. Means and standard deviations for the overall treatment effect and each study-specific treatment effect were estimated from these empirical distributions, and 95 percent probability intervals were computed.

The robustness of our conclusions to our model assumptions was assessed through sensitivity analysis. Because the random-effects approach involves estimation of the between-study variance of the study-specific effects, the estimate of the overall treatment effect for each of the two outcomes will be affected most by assumptions about the size of this parameter. Thus we varied our assumed precision for the prior distribution of the between-study variance. We also assessed the sensitivity of the overall effect estimate to the inclusion of each individual study by systematically eliminating studies, reestimating the hierarchical linear model, and examining the size of the overall treatment effect. Finally, fixed-effects estimates—those that assume no between-study variance—are presented for comparison purposes.

Results

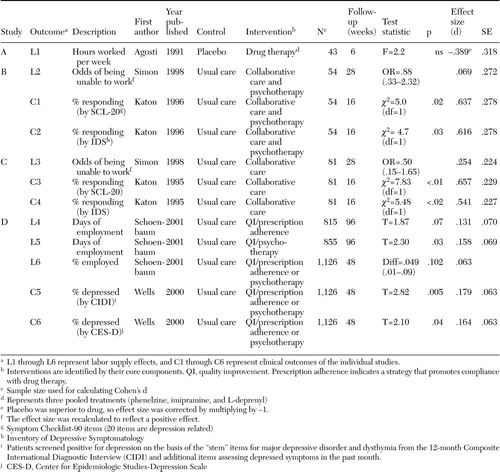

Our database searches identified an initial set of 706 articles, but only four studies met our inclusion criteria. In each case, clinical results and labor supply effects were collected from separate articles, except in the case of the study by Agosti and colleagues (24), for which appropriate clinical results could not be found.

Characteristics of the studies are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. All trials were conducted in the United States during the years 1991 to 2001. The number of study participants ranged from 43 to 1,126, and participants were followed for periods ranging from six weeks to two years. The mean age of participants across studies was 41.2 years (range, 35.0 to 43.7), and a majority of participants were women (mean, 69 percent; range, 53 to 82 percent).

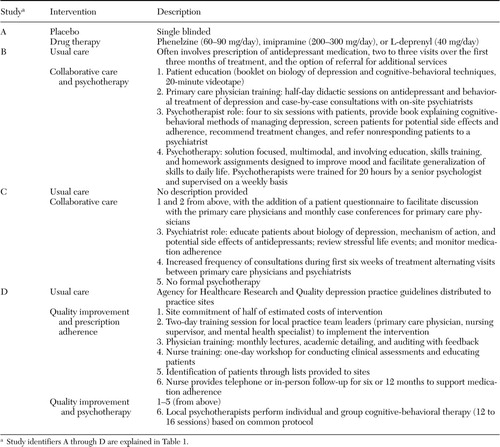

The four trials included in this meta-analysis differed in a number of important ways, most notably in their design. The study by Agosti and colleagues (24) was an efficacy trial that compared antidepressants with placebo, whereas the other three trials evaluated primary care-based quality improvement strategies aimed at providing an enhanced level of care (25,26,27). Most of the latter interventions included psychotherapy or a strategy to increase medication compliance in addition to physician and nurse education, patient education, and improved access to specialists. The two studies by Katon and colleagues (25,26) and one by Wells and colleagues (27) are known as "encouragement" studies in that a collaborative approach to treatment was sought but patients were not required to participate and providers were not required to comply with a formal protocol. Table 2 shows more detail of the specific interventions that were compared in these trials.

In addition to differences in design, each study used a variety of measures to assess the labor market effects of the interventions. The Agosti study compared the number of hours worked each week between intervention and control groups, whereas the Katon studies measured the impact of the intervention in terms of greater odds of working at follow-up. The Wells study measured both the number of days worked in two separate intervention strategies—psychotherapy and prescription adherence—compared with usual care, in addition to assessing differences in employment rates at follow-up (comparing the pooled intervention strategies with usual care).

Studies varied in their exclusion of persons with severe mental illness. The Katon studies explicitly excluded psychotic and suicidal persons and those with comorbid dementia or substance abuse, whereas the Agosti study did not indicate the presence of any concurrent mental illnesses in its sample. In contrast, the Wells study included participants with bipolar or alcohol use disorders. In addition, the populations were not homogeneous in terms of severity of depression. In the Katon studies, results for major and minor depression were reported separately. In the Agosti study, 25 percent of patients had major depressive disorder, 31 percent had dysthymia, and 44 percent had both major depression and dysthymia, but the effects on labor output were not stratified accordingly. The Wells study did not describe the sample's depression severity, although it reported that about half the sample had a depressive disorder of at least 12 months' duration.

Not all results from the included studies could be used in our analysis. Reasons for exclusion of individual effect estimates were missing baseline employment information (Wells), the fact that days of work missed were combined with school days missed (Katon), stratification of an outcome by patients' clinical response status (Katon), and use of a work functioning scale (Agosti).

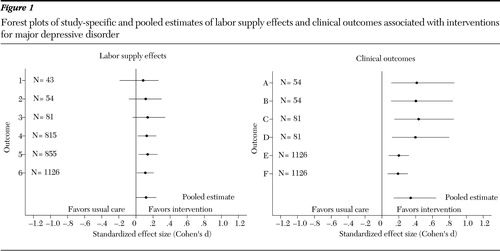

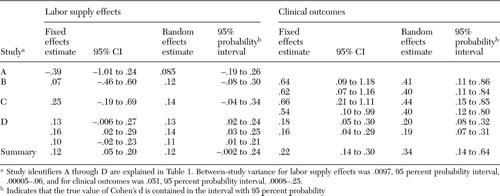

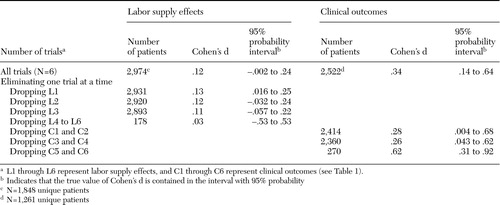

This meta-analysis indicated that interventions for depression have significant clinical and labor market benefits. The labor supply effect of the interventions was .12 (95 percent probability interval, -.002 to .24), and the effect on clinical outcomes was almost three times as large at .34, with a 95 percent probability interval of .14 to .64. These results are presented in the form of a forest plot (Figure 1) and in tabular form (Table 3). The results suggest that the mean labor supply effect for the intervention groups compared with the control condition differed by about .1 of a standard deviation, whereas the mean clinical benefit between the two groups differed by about one-third of a standard deviation. Repeated simulations indicated that the probability that the intervention had an effect on labor supply was small—for example, .2 on the Cohen's d scale is estimated to be only .07 but is .90 for the clinical benefit.

Changing the prior mean and variance of the between-study variance distribution over a range of plausible values did not substantially change our results. For example, when the precision of the between-study variance was decreased by a factor of 1,000, our estimate of the mean effect on labor supply changed from .12 to .13. When the precision of the variance for the clinical outcomes was altered in the same manner, the mean clinical effect decreased from .34 to .29. Given the small number of studies, the overall results were sensitive to the elimination of an individual study's set of results (Table 4). The mean labor supply effect of the modified sample ranged from .03 to .13, whereas the mean clinical effect of the interventions ranged from .26 to .62. The results were most sensitive to the elimination of the estimates from the Wells study, which carried considerable weight in the main analysis because of their high precision.

Discussion

Our results suggest that patients with major depressive disorder benefit from the various interventions that were studied. Significant reductions in symptom severity were observed. However, the overall gain in labor output was only a third as large as the reductions in symptom severity. The fact that follow-up times for all economic end points were equal to or exceeded those for the clinical end points makes this finding even more significant. To the extent that the labor market benefits of interventions are lagged, insufficient follow-up times for the labor supply outcomes mitigated against finding larger effects. Indeed, only the study by Wells and colleagues (27), which indicated the largest gains in labor output, allowed two years of follow-up. Other explanations include the possibility of lower treatment-responsiveness for the psychological-behavioral domains that contribute to labor market participation and the potentially greater impact of market structure on labor supply, which is unaffected by these interventions.

Another possible explanation for the small labor supply effects is that the benchmarks commonly used to assess the practical significance of values of Cohen's d are inappropriate for labor market outcomes. Ideally, the effect of an intervention is measured against meaningful effect sizes from previous research that both assessed labor market outcomes and used Cohen's d as a measure of effect. However, such studies could not be found. Although the labor supply effects appear small when interpreted with benchmarks commonly used in the social sciences, they might be substantively significant.

The design of the trials used in our meta-analysis might have caused us to underestimate the clinical and economic gains from depression-related interventions. The participants who were enrolled in the intervention groups of the encouragement trials might have shunned higher levels of care, and primary care physicians might have varied in their enthusiasm for providing treatment. Thus lower rates of provision of care in the intervention groups are to be anticipated in studies with this design. On the other hand, because evidence-based treatments cannot ethically be withheld—and nor should they be—usual care groups in encouragement trials are also likely to obtain enhanced care. In fact, the Wells study indicates that members of the usual care group received a substantial level of evidence-based care. Thus so-called contamination of both intervention and control groups might have caused an underestimation of the impact of interventions. However, it is important to note that this phenomenon does not account for the difference between the clinical and labor supply benefits we found.

As with any meta-analysis, we cannot exclude the possibility that smaller studies or studies published in lower-impact journals were missed during the database search, or that studies that reported null effects were absent from the literature altogether. Although such a possibility is purely speculative, the greater variability in this class of outcomes suggests that individual trials are underpowered to detect these effects. Accordingly, the effects we found in the published literature might have caused us to overstate the true economic benefit of depression-related interventions. Thus the observed difference between the clinical and labor supply effects is difficult to interpret because of two potential sources of bias simultaneously affecting the economic outcomes: (upward) publication bias and the (downward) bias due to their greater underlying variability vis-à-vis clinical outcomes.

The small number of studies might raise concerns about the precision of our estimates and generalizability of our conclusions. Whereas typical meta-analyses combine a single summary statistic from each study, our analysis used multiple economic and clinical outcomes for each study in an attempt to pool as much information as possible. Because outcomes from the same study are not statistically independent, our approach would have overestimated the precision of the overall results. However, it is unlikely that this overestimation affected the overall study conclusions. Because we did not have access to patient-level data, we cannot be sure that the participants who improved clinically were the same ones who experienced labor-related benefits. Thus our results should not be used to make inferences about the joint effect of these two outcomes for any particular individual.

Alternative measures of labor market effects of depression interventions might have been considered, such as "presenteeism" (reduced functioning while at work). However, this measure has been noted as being subject to recall bias and subjectivity (28). Assessing changes in labor output provides an objective measure of impact that is useful to policy makers and employers wanting to sponsor depression-related interventions.

Conclusions

Results from randomized controlled trials suggest that interventions for patients with major depression can reduce depressive symptoms and increase labor output. The labor supply benefits are small relative to the improvement in clinical outcomes. The difference in effects might be due to a different underlying efficacy, a relatively brief duration of follow-up, or to extrinsic factors that affect labor supply.

The authors are affiliated with the department of health care policy of Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Avenue, Suite 301, Boston, Massachusetts 02115 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Forest plots of study-specific and pooled estimates of labor supply effects and clinical outcomes associated with interventions for major depressive disorder

|

Table 1. Characteristics of studies eligible for a meta-analysis of interventions for major depressive disorder

|

Table 2. Characteristics of study participants in the intervention group in trials eligible for a meta-analysis of interventions for major depressive disorder

|

Table 3. Study-specific and summary effects of interventions on labor supply and clinical outcomes

|

Table 4. Sensitivity of overall results to the exclusion of individual studies

1. Ettner SL, Frank RG, Kessler RC: The impact of psychiatric disorders on labor market outcomes. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 51:64–81,1997Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Frank RG, Koss C: Mental Health, Labor Market Productivity Loss, and Restoration. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2004Google Scholar

3. Ruhm CJ: The effects of physical and mental health on female labor supply, in Economics and Mental Health. Edited by Frank RG, Manning WG. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992Google Scholar

4. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Rockville, Md, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

5. Kennedy JF: Message from the President of the United States Relative to Mental Illness and Mental Retardation. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1963Google Scholar

6. Harwood H, Fountain D, Livermore G: The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse in the United States, 1992. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1998Google Scholar

7. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1999Google Scholar

8. Wang PS, Simon G, Kessler RC: The economic burden of depression and the cost-effectiveness of treatment. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 12:22–33,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, et al: Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 264:2524–2528,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Dewa CS, Hoch JS, Lin E, et al: Pattern of antidepressant use and duration of depression-related absence from work. British Journal of Psychiatry 183:507–513,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Miller IW, Keitner GI, Schatzberg AF, et al: The treatment of chronic depression: III. psychosocial functioning before and after treatment with sertraline or imipramine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59:608–619,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, et al: Cost-effectiveness of practice-initiated quality improvement for depression: results of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 286:1325–1330,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Simon GE, Revicki D, Heiligenstein J, et al: Recovery from depression, work productivity, and health care costs among primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 22:153–162,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Hirschfeld RM, Dunner DL, Keitner G, et al: Does psychosocial functioning improve independent of depressive symptoms? A comparison of nefazodone, psychotherapy, and their combination. Biological Psychiatry 51:123–133,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Simon GE, Katon W, Rutter C, et al: Impact of improved depression treatment in primary care on daily functioning and disability. Psychological Medicine 28:693–701,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, McCaffrey D, et al: The effects of primary care depression treatment on patients' clinical status and employment. Health Services Research 37:1145–1158,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Mintz J, Mintz LI, Arruda MJ, et al: Treatments of depression and the functional capacity to work. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:761–768,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Berndt ER, Finkelstein SN, Greenberg PE, et al: Workplace performance effects from chronic depression and its treatment. Journal of Health Economics 17:511–535,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Rosenthal R: Parametric measures of effect size, in The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Edited by Cooper H, Hedges L. New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1994Google Scholar

20. Rosenthal R: Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1991Google Scholar

21. Normand SL: Meta-analysis: formulating, evaluating, combining, and reporting. Statistics in Medicine 18:321–359,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. DuMouchel W, Normand S: Computer-Modeling and Graphical Strategies for Meta-analysis. New York, Marcel Dekker, 2000Google Scholar

23. Spiegelhalter DJ, Thomas A, Best NG, et al: BUGS: Bayesian Inference Using Gibbs Sampling, 1996Google Scholar

24. Agosti V, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM: Life satisfaction and psychosocial functioning in chronic depression: effect of acute treatment with antidepressants. Journal of Affective Disorders 23:35–41,1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273:1026–1031,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:924–932,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al: Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 283:212–220,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Wang PS, Beck AL, Berglund P, et al: Effects of major depression on moment-in-time work performance. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1885–1891,2004Link, Google Scholar