Implementation and Maintenance of Quality Improvement for Treating Depression in Primary Care

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Little is known about the long-term success of quality improvement efforts for the treatment of depression in primary care. This study assessed factors associated with the successful implementation, maintenance, and spread of such efforts. METHODS: The authors conducted an independent process evaluation of data from monthly progress reports and 18-month telephone interviews from multidisciplinary quality improvement teams in 17 diverse primary care organizations that participated in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Breakthrough Series for Depression from February 2000 through March 2001. RESULTS: All sites made changes toward improving care in three of six categories: delivery system redesign, self-management strategies, and information systems. The changes that were most commonly viewed as major successes were delivery system changes (ten sites, or 59 percent) and information system changes (nine sites, or 53 percent); these types of changes were also the most often sustained over time (ten sites, or 59 percent, and 16 sites, or 94 percent, respectively). Fifteen sites made changes in decision support, community linkages, and health system support but were less likely to view these changes as major successes or to sustain them. Organizational structure and leadership support were the most common facilitators. Staff resistance, time constraints, and information technology were the most common barriers. Implementation strategies varied with sets of barriers. CONCLUSIONS: Despite substantial challenges, there was evidence of broad success at implementation and maintenance of quality improvement for depression treatment in primary care.

Depression is a common chronic illness with unique attributes that may hinder implementation of quality improvement in primary care. Compared with physical diseases, mental illnesses are associated with greater stigma and are frequently underrecognized in primary care (1,2,3). Treatment adherence is problematic, with up to a third of patients discontinuing medications after one month (4). Other challenges to treating depression in primary care include time-constrained patient visits, difficulty coordinating care with mental health specialists, limited reimbursement for evidence-based depression treatments, and limitations in practice structure to accommodate depression care (5,6), particularly for practices that serve disadvantaged populations.

Recent studies have demonstrated that quality-improvement efforts can be successful for improving the processes and outcomes of depression treatment in primary care. However, these studies have been conducted and implemented under favorable circumstances: either in large, integrated systems of care (7) or by researchers with substantial external grant funding (8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15). Little is known about how teams of primary care providers can put these models into action locally and how well changes from these efforts are sustained over time.

Our descriptive and formative evaluation of quality improvement processes by 17 diverse organizations that participated in the Depression Breakthrough Series collaborative, a 13-month initiative applying principles from the Chronic Care Model to improve depression care (16,17), was guided by the literatures on diffusion of innovations and social psychological influences on behavior (18,19,20). This literature emphasizes the role of contextual factors (for example, group norms, organizational infrastructure, and availability of resources) and social psychological processes (for example, perceived trade-offs between benefits and barriers) (21,22) in enabling or constraining systemic change in health care organizations. Because quality improvement initiatives represent a process of organizational change that occurs over time, we studied initial adoption of innovations as well as whether they persist and become institutionalized in routine practice (22).

This study addressed the critical gap in the health care literature by considering multiple dimensions of implementation "success." We examined in detail the process of implementing and maintaining change to understand how teams adopt innovative and evidence-based practices for depression care. We specifically focused on three research questions. First, which features of the Depression Breakthrough Series were successfully implemented? Second, what barriers and facilitators did quality improvement teams experience during implementation? Third, how were contextual factors, barriers, and facilitators associated with successful implementation, maintenance, and spread of changes in depression care?

Methods

Collaboratives and the chronic care model

Twenty-three primary care organizations voluntarily enrolled in the Depression Breakthrough Series. This intervention was coordinated by the Improving Chronic Illness Care team and the Institute for Health Care Improvement and supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Six private-sector organizations each paid a fee of $12,500, and 11 public-sector organizations that were financed by the Health Resources and Services Administration received a scholarship from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to cover the fee. Each team (typically a physician, a care manager, and a coordinator) attended three learning sessions for training by institute faculty on "plan-do-study-act" cycles and other techniques for rapid quality improvement and by experts in implementing the chronic care model. Between sessions, teams attempted to make changes and participated in monthly cross-site conference calls with expert faculty.

On the basis of the chronic care model, which envisions the delivery of effective treatment for chronic illness by restructuring care systems, teams were encouraged to design programs that implement changes within each of six areas: delivery system design, self-management strategies, decision support, clinical information systems, community linkages, and health system support. Additional details of the design and evaluation of the 13-month collaboratives (February 2000 through March 2001) (23,24) and the organization of the Depression Breakthrough Series (14) are reported elsewhere. All procedures were reviewed and approved by RAND's institutional review board and the boards at collaborating sites.

Study participants

Of the 23 organizations that were initially enrolled in the collaborative, two did not assemble a team, two dropped out, and two (school-based organizations) were not eligible for our evaluation, which targeted adults. Of the 17 remaining sites, 11 were community health centers supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration's Bureau of Primary Health Care, serving disadvantaged populations with a high proportion of minority patients, and six were private community-based organizations (a nurse-managed facility within a public housing community, an integrated care system of hospitals and outpatient clinics, two health systems with academic affiliations, an independent small-group practice, and a nonprofit organization serving Native Americans in remote villages). Some sites received funding to facilitate recruitment into the RAND evaluation. A few sites had participated in the diabetes collaborative that was implemented before the depression collaborative.

Data sources and measures

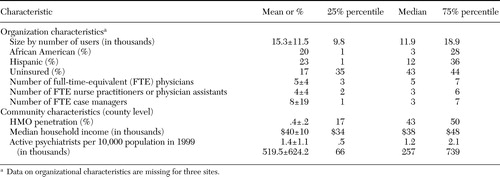

We collected information about the organizations' clients (number of users, ethnicity, and insurance status) and clinical staff (number of full-time-equivalent clinicians) through correspondence with team leaders (for private sites; data are missing for three sites) or from the central Uniform Data System (for public sites). Information about community characteristics (HMO penetration, median household income, psychiatrist volume, and population) was obtained for all sites from the Department of Health Services Area Resource File, linked by county identification code (25).

Organization and community characteristics of the 17 participating organizations are shown in Table 1. Organizations represented all geographic regions of the United States, varying widely in size of client population, minority representation, and number of uninsured clients. Communities represented a broad range of HMO penetration in the local county health care market, median household income, and distribution of psychiatrists.

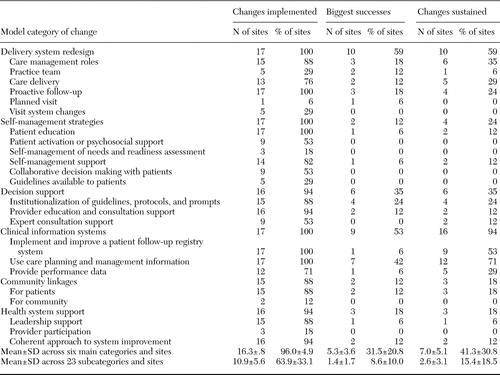

We coded the latest monthly cumulative summary progress report of intervention activities in the collaborative filed by each team leader (26). We assigned all change activities to two-level hierarchical categories (23 subcategories that aggregate up to six broad categories of the chronic care model). The coding categories and the number and percentage of sites that reported changes, by category, are listed in Table 2.

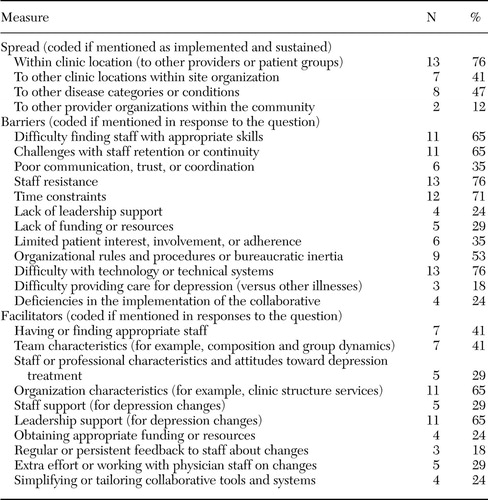

We also coded qualitative data from semistructured telephone interviews conducted approximately 18 months after the end of the collaborative with team leaders (from April 2002 through December 2002). During these one-hour discussions, we asked leaders to look back at their efforts and tell us what they would consider as their biggest successes. We also asked which changes were sustained and why, and asked respondents to identify major barriers (and facilitators, some of which were the converse of a barrier) to change. We used the same 23-category coding scheme to code biggest successes and changes sustained. We used custom-tailored categories (Table 3) to code type of spread (for example, diffusion with use of the Rogers framework) (18,22) as well as facilitators and barriers to improving depression care.

In addition, we asked team leaders to estimate staffing and resources required by the collaborative and used these estimates to compute the costs of participation (attendance at learning sessions, participation in weekly teleconferences, and preparation of monthly reports) and of noncollaborative tasks (designing or developing interventions and spreading change). We converted labor time into costs by multiplying each person's reported hours by an average wage rate for that individual's professional group (for example, physician, nurse, management, or information technology [IT] specialist).

Analysis

Here we present univariate analyses to describe the teams' quality improvement process outcomes (change implementation, successes, maintenance, and spread) and the facilitators and barriers reported in achieving these outcomes. We then present bivariate associations between the process outcomes and barriers and facilitators. We complement these analyses with network analysis (27,28) of patterns among barriers and organizational and community characteristics.

Results

Intercoder agreement

Two evaluation team members independently coded the change activities from senior leader reports (26) and the other five measures (successes, maintenance, spread, barriers, and facilitators) from the telephone interviews. Initial reliability between coders, based on kappa coefficients, ranged from .52 for facilitators to .80 for spread. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Changes implemented

All 17 sites made changes to their delivery systems, self-management strategies, and information systems (Table 2); all sites reported some proactive follow-up, patient education, improvements in follow-up through use of a patient registry (required by the collaborative), and use of data from information systems for care management. All but two sites made changes in decision support, community linkages, and health system support.

Self-rated successes

Slightly more than half the sites made changes to delivery system redesign (ten sites, or 59 percent) and information systems (nine sites, or 53 percent) that were "big successes." Although all sites reported changes to improve patient education, and the vast majority tried to improve self-management support (14 sites, or 82 percent), only one site reported a "success" in these areas. Only one site (6 percent) reported no successes, three sites (18 percent) reported success in only one category (delivery system redesign or decision support), four sites (24 percent) reported success in three categories, and nine sites (53 percent) reported success in two categories.

Changes sustained

More sites sustained change in information systems than in any other category (16 sites, or 94 percent). Twelve sites (71 percent) sustained changes to improve the use of care planning and management information, nine (53 percent) to implement or improve patient follow-up by using a depression registry, and five (29 percent) to provide performance data by using information systems. Ten sites (59 percent) reported sustaining delivery system redesign, including care management roles, care delivery, and proactive follow-up.

Spread of collaborative efforts

Fifteen sites (88 percent) reported some form of spread (Table 3), most commonly to other providers or patient groups within the same location (13 sites, or 76 percent), followed by spread to other disease categories or conditions—including joining other collaboratives (eight sites, or 47 percent)—and then to other clinics in the same organization (seven sites, or 41 percent). Only two sites (12 percent) reported spread to other organizations within the community.

Facilitators and barriers to change

Across all sites, organization or site-specific attributes (for example, clinic structure and location) and leadership support were the most frequently reported facilitators to implementing improvements (11 sites, or 65 percent, for both) (Table 3). Having appropriate staff and effective team characteristics were other commonly reported facilitators (seven sites, or 41 percent, for both). The most common barriers to success included staff resistance to changes (mostly on the part of primary care providers), difficulty with IT or technical systems (both reported by 13 sites, or 76 percent of sites), time constraints (12 sites, or 71 percent), difficulty finding appropriate staff (11 sites, or 65 percent), and retaining staff (11 sites, or 65 percent, for both).

Contextual characteristics and implementation

We observed significant positive correlations (data not shown) for the total number of changes among sites (N=17) in communities with higher median household incomes (r=.51, p=.04) and with more psychiatrists (r=.55, p=.02). For big successes, we observed a significant negative association for sites with more uninsured persons (r=.-60, p=.02). No site characteristics were associated with maintenance or spreading of changes. Sites in communities with more Hispanic clients (r=.50, p=.08) and more uninsured persons (r=.61, p=.03) reported more facilitators (mean±SD=3.6±1.8), and sites with more nonphysicians per 10,000 population reported more barriers (5.7±2.2, r=.56, p=.04).

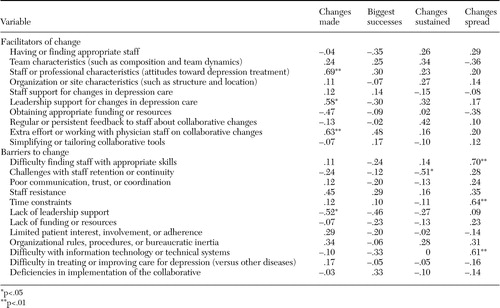

Barriers and facilitators of implementation

Among facilitators, staff characteristics (for example, staff attitudes toward depression treatment, leadership support, and efforts made to work with physicians) were positively associated with change (r=.69, .58, and .63, respectively) (Table 4), and successfully obtaining resources was negatively associated with change (r=-.47, p=.06). The staff resistance barrier was positively correlated with change (r=.45, p=.07), and lack of leadership support was negatively associated with change (r=-.52, p=03).

Only one facilitator (extra efforts made to work with physician staff) and one barrier (lack of leadership support) trended toward significant associations with the number of perceived big successes (r=.48 and -.46, respectively) (Table 4).

For maintenance, a positive trend was observed for association between regular feedback to staff about collaborative changes and changes sustained (r=.42, p=09), and staff retention barriers were negatively associated with less change maintenance (r=-.51, p=.03).

No facilitators were significantly associated with spread. However, perceived barriers—including difficulty finding and keeping the right staff (r=.70, p=.002), time constraints (r=.64, p=.006), and IT problems (r=.61, p=.009)—were positively associated with spread.

Network analysis

Network analysis using NetDraw (29) displays the raw data to illustrate the complexity of important relationships—for example, how different changes sustained (Table 2) were linked to unique sets of barriers (Table 3) across sites. This approach allows a third variable, such as a client characteristic, to be added. [A figure illustrating these links is available in the online version of this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Implementation costs

We estimated the average cost of participating in the collaborative and implementing quality improvement at $118,000 per site, ranging from $30,000 to $252,000 (SD=$72,000). The large variation across sites was attributable mainly to the number of pilot patients (r=.49) and the number of physicians actively involved in the collaborative (r=.81). The mean cost per patient was $879 (only $375 at sites with 300 or more pilot patients). Nursing staff generally accounted for the largest share of costs, and physicians accounted for about 20 percent of labor hours.

Discussion

We found significant and enduring changes to improve care for depression in a variety of primary care practices that participated in the Depression Breakthrough Series Collaborative. Teams made improvements despite the many challenges associated with delivering depression care, particularly in the underserved areas in which participating clinics were located, which suggests that even sites that serve many minority clients benefited from the quality improvement effort (29).

Moreover, changes were made at a relatively low cost that was commensurate with rates found in other cost-effectiveness studies (30). Although it is known that quality improvement interventions with multifaceted teams that use evidence-based practices can have positive effects on care for depression and its outcomes (8,9), we know little about how the complex process unfolds at the team and practice levels. To address this gap we have described the types of changes that teams made and explored characteristics that are linked with successful implementation, maintenance, and spread of improvements for depression.

Our data suggest some lessons for using collaborative approaches to improve depression in primary care settings. First, although some changes were adopted by all the teams (proactive follow-up, patient education, patient registry systems, and care planning), other types of changes were not (provider participation and patient activation). This pattern suggests that future collaboratives teach how to obtain this fruit at the top of the tree.

Implementation of change was consistent with the guidance provided by the collaborative faculty, who emphasized the role of care managers (for example, redesign of the delivery system) and patient registries (for example, information systems). These areas are critical, but the uneven emphasis on certain categories of change is inconsistent with the model's objective of achieving success across all six categories.

Quality improvement efforts are more likely to be maintained over time if they involve input from all relevant parties, especially top management. Furthermore, teams that may not have had buy-in at all three levels (patients, clinicians, or other organizations) faced additional challenges to comprehensive change. Rubenstein and colleagues (7) found that teams reported support from organizational leadership to be an important facilitator for successful quality improvement in depression care. Similarly, in this study, the only barrier that significantly affected perceived success was poor leadership support. For example, although one organization faced severe financial limitations, the chief executive officer's strong advocacy for the depression program and support through "in-kind" resources was critical in the survival and effectiveness of the collaborative team. In another organization, changes were implemented mainly after the end of the collaborative, when a more sympathetic leader was hired. Consistent with the finding of Goldman and colleagues (31), these results suggest that implementation of evidence-based services requires having appropriate incentives in place and the ability to overcome systemic barriers.

We also found that smaller clinics were more likely to sustain change over time. In a smaller practice, a quality improvement project may be more visible and easier to manage by a few dedicated individuals. By contrast, such efforts may be susceptible to dilution in larger systems of care, or there may be other competing quality improvement efforts. Another explanation is the relative ease of reaching critical mass through training investments in smaller organizations to sustain team efforts.

Sites that were particularly successful at implementing and sustaining changes were less likely to spread those changes. This finding may be related to the need to institutionalize changes in the initial setting before extending them. Also, as noted above, many sites that were successful at sustaining changes were smaller, which may reflect less need, pressure, or even opportunity to spread, if all or most of the site was included in the initial implementation.

The finding that sites that spread innovations to other patient groups or locations reported more barriers could become manifest as barriers emerge or become apparent (when the scope of changes begins to affect wider portions of the care system). In contrast, change efforts that remain limited in scope or depth would encounter few points of resistance. Thus an increased elicitation of barriers may in fact be a corollary to success, at least in terms of spread. Alternatively, in certain sites with fewer initial changes, expansion of change activities after the collaborative period may signify delayed implementation rather than actual spread. This possibility could also partially explain the negative correlation between having obtained adequate resources and the amount of change reported during the collaborative.

Some specific challenges identified by participants included language barriers that made hiring and retaining qualified staff daunting in sites with larger Hispanic populations. Moreover, the qualitative descriptions of implementation process from the interviews emphasized the interrelatedness of barriers—for example, trouble developing workable computerized systems was frequently blamed on lack of appropriately skilled staff as well as on difficulty arranging dedicated staff for updating and managing depression registries (often manual or incompletely automated). In turn, difficulty with registries was noted to limit spread. Likewise, the strategy of devoting extra effort to get physician staff to accept and implement changes (by nearly a third of the sample) occurred only at sites that also reported staff resistance and was accompanied by more change activity. This pattern suggests that such a concerted and persistent approach with physicians proved effective in the face of substantial staff resistance.

Although this study has extended research on quality improvement by assessing success of implementation in detail over many dimensions and across more sites than is typical in such research, the analyses had several limitations. First, although a sample of 17 sites is large for such studies, its statistical power is limited to detecting significant site-level differences. Consequently, several hypothesized and plausible correlations, although high, were not significant. Furthermore, the sample of organizations was heavily weighted toward public-sector community clinics that serve predominantly disadvantaged populations and, although geographically diverse, might preclude generalization of findings to all primary care practices. This study was also restricted to self-reported data, which could be subject to inaccurate retrospective recall and even optimistic bias, particularly regarding spread, because team leaders may lack full knowledge of the actual degree of implementation beyond their site. Finally, the inability to collect enough patient-level outcome data for participants in this particular collaborative prevented us from relating implementation success to the health and functioning of individuals who were receiving care.

Nonetheless, our findings suggest that a number of changes, such as the use of care planning and management information, may be relatively easy to implement and sustain, whereas other changes, such as provider participation and patient activation, although equally important, are more difficult. Unlike for diabetes care, few organizations reported success in the area of self-management of depression. In general, the review of barriers and facilitators suggests that quality improvement for depression may require extra attention or resources, or different strategies with clinicians to successfully implement participatory practice changes and activate patients (32), because staff attitudes are an important factor in implementing change efforts (33).

Conclusions

Although the organizations that participated in this study accomplished a great deal in efforts toward improving depression care, quality improvement teams did not sustain all their changes after the end of the collaborative. Future collaboratives that target improvements in depression care should pay particular attention not only to initiating change but also to sustaining and spreading changes over time. Use of other strategies for implementing evidence-based practices, such as aligning incentives (34,35), are also worthy of integration into future collaboratives. Specific types of improvements were associated with organizational and community characteristics, and similar organizations faced challenges from similar sets of barriers. Our detailed findings about implementing quality improvement should help guide future efforts to improve chronic illness care.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants 034984 and 035678 from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors thank Julie Brown and Rosaelena Garcia for organization recruitment and data collection; Joan Keesey, Chantal Avila, Scott Hickey, and Afshin Rastigar for data management and analysis; and Matt Schonlau for statistical consultation.

All authors except Dr. Unützer are affiliated with RAND Corporation, 1776 Main Street, Santa Monica, California 90407-2138 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Unützer is with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 17 organizations that participated in the Institute for Healthcare Improvements Breakthrough Series for Depression

|

Table 2. Numbers and percentage of 17 sites that reported changes in depression care and number of changes made for each category of the chronic care model (N=23)

|

Table 3. Number and percentage of 17 sites that reported spread of, facilitators of, and barriers to quality improvement in depression care

|

Table 4. Bivariate associations (Spearman correlations) of facilitators and barriers with implementation outcomes at 17 sites that participated in the Institute for Healthcare Improvements Breakthrough Series for Depression

1. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al: The national depressive and manic-depressive association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 277:333–340,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke Jr JD, et al: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:977–986,1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wells KB, Katon W, Rogers B, et al: Use of minor tranquilizers and antidepressant medications by depressed outpatients: results from the medical outcomes study. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:694–700,1994Link, Google Scholar

4. Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W, et al: The role of the primary care physician in patients' adherence to antidepressant therapy. Medical Care 33:67–74,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Nutting PA, Rost K, Smith J, et al: Competing demands from physical problems: effect on initiating and completing depression care over 6 months. Archives of Family Medicine 9:1059–1064,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Rost KM, et al: Treating depression in staff-model vs network-model managed care organizations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 14:39–48,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Rubenstein LV, Parker LE, Meredith LS, et al: Understanding team-based quality improvement for depression in primary care. Health Services Research 37:1009–1029,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Schoenbaum M, et al: Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:212–220,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al: Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:2836–2845,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Katon W: The impact of major depression on chronic medical illness. General Hospital Psychiatry 18:215–219,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273:1026–1031,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al: Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the quest intervention. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16:143–149,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hunkeler EM, Meresman JF, Hargreaves WA, et al: Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Archives of Family Medicine 9:700–708,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Katzelnick DJ, VonKorff M, Chung H, et al: Applying depression-specific change concepts in a collaborative breakthrough series. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety 31:386–397,2005Google Scholar

15. Simon GE, Revicki D, Heiligenstein J, et al: Recovery from depression, work productivity, and health care costs among primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 22:153–162,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. The Chronic Care Model. Princeton, NJ, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Improving Chronic Illness Care. Available at www.improvingchroniccare.orgGoogle Scholar

17. Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, Davis C, et al: Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach. Joint Commission Journal of Quality Improvement 27:63–80,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Rogers E: Diffusion of Innovations. 4th ed. New York, Free Press, 1995Google Scholar

19. Strang D, Soule SA: Diffusion in organizations and social movements: from hybrid corn to poison pills. Annual Review of Sociology 24:265–290,1998Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology 3:265–299,2001Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Becker MH, Maiman LA: Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Medical Care 13:10–24,1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Van de Ven A, Polly D, Garud R: The Innovation Journey. New York, Oxford University Press, 1999Google Scholar

23. Cretin S, Shortell SM, Keeler EB: An evaluation of collaborative interventions to improve chronic illness care: framework and study design. Evaluation Review 28:28–51,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Improving Chronic Illness Care Evolution: A RAND Health Program. Santa Monica, Calif, RAND. Available at www.rand.org/health/icice/Google Scholar

25. US Bureau of Health Professions: Area resource file [computer tapes and user documentation]. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, 2001Google Scholar

26. Pearson ML, Wu SY, Schaefer J, et al: Assessing the implementation of the Chronic Care Model in Quality Improvement Collaboratives. Health Services Research 40:978–996,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Borgatti SP, Foster P: The network paradigm in organizational research: a review and typology. Journal of Management 29:991–1013,2003Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Borgatti SP: NetDraw: Network Visualization Software, version 1.0.0.21. Cambridge, Mass, Analytic Technologies, 2002Google Scholar

29. Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al: Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized controlled trial. Health Services Research 38:613–630,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, et al: Cost-effectiveness of practice-initiated quality improvement for depression: results of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 286:1325–1330,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Goldman HH, Ganju V, Drake RE, et al: Policy implications for implementing evidence-based practices. Psychiatric Services 52:1591–1597,2001Link, Google Scholar

32. Pincus HA, Hough L, Houtsinger JK, et al: Emerging models of depression care: multi-level ("6 P") strategies. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 12:54–63,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Aarons G: Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research 6:61–74,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Frank RG, Huskamp HA, Pincus HA: Aligning incentives in the treatment of depression in primary care with evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 54:682–687,2003Link, Google Scholar

35. Katon WJ, Unützer J, Simon G: Treatment of depression in primary care: where we are, where we can go? Medical Care 42:1153–1157,2004Google Scholar