Brief Reports: Patterns of Psychotropic Medication Use by Race Among Veterans With Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study investigated whether race was associated with patterns of psychotropic medication use among veterans with bipolar disorder. METHODS: Data were examined for veterans from the mid-Atlantic region with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in fiscal year 2001. Prescription data determined whether differences existed between black and nonblack patients in the receipt of lithium, other mood stabilizers, all mood stabilizers, first-generation antipsychotics, second-generation antipsychotics, all antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, all antidepressants, and benzodiaze-pines. RESULTS: Data for 2,958 patients were sampled: 347 blacks and 2,611 nonblacks. Multivariable analyses that adjusted for patient and clinical factors revealed that compared with nonblacks, blacks were significantly less likely to receive lithium and SSRIs and significantly more likely to receive first-generation antipsychotics and any antipsychotic. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest that efforts should be made to reduce disparities in access to pharmacotherapy among patients with bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorder is a recurrent and chronic mental illness associated with functional impairment and significant health care costs (1,2). Inadequate pharmacotherapy for patients with bipolar disorder may lead to adverse health outcomes (1). Evidence suggests that blacks are less likely than whites to receive adequate pharmacotherapy for unipolar depression (3,4) and schizophrenia (5). However, the extent to which blacks are receiving adequate pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder has not been studied (3). Bipolar disorder provides an ideal example for studying patterns of psychopharmacologic medication use by race, because a number of psychotropic medications are used to manage symptoms related to bipolar disorder—for example, mood stabilizers and antidepressants. Hence, we sought to determine whether race was associated with patterns of medication use among a population-based sample of patients who were receiving care for bipolar disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of secondary data for all patients who had been given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in fiscal year 2001 (October 1, 2000, through September 30, 2001) and had received care at facilities within the VA Stars and Stripes Integrated Services Network. The network includes facilities in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and areas of West Virginia, Ohio, New Jersey, and New York. We identified all patients with either an inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of bipolar disorder (I, II, or not otherwise specified) or cyclothymia from the VA National Patient Care Database by using ICD-9 codes 296.0x, 296.1x, 296.4x through 296.8x, and 301.13. We limited the sample to patients with either one inpatient or two separate outpatient visits with a recorded diagnosis of bipolar disorder in order to maximize the specificity of diagnoses and limit diagnoses given to rule out a disorder (6). This study was reviewed and approved by local institutional review boards of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System.

Psychopharmacologic prescription data were ascertained from the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Database from fiscal year 2001. We ascertained whether patients received a prescription from the date of the index bipolar diagnosis up to 12 months after the index diagnosis for at least one medication from each of the following categories: lithium, mood stabilizers other than lithium, first-generation antipsychotics, second-generation antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, antidepressants other than SSRIs or tricyclics, and benzodiazepines.

Specifically, other mood stabilizers included divalproex, valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine. First-generation antipsychotics included chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, mesoridazine, thiothixene, perphenazine, thioridazine, trifluoperazine, haloperidol, loxapine, and molindone. Second-generation antipsychotics included clozapine, olanzapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. SSRIs included fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, and citalopram. Tricyclics included ami-triptyline, amitriptyline pamoate, clomi-pramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, nortriptyline, protriptyline, trimipramine, and amoxapine. Other antidepressants included bupropion, venlafaxine, maprotiline, trazodone, mirtazapine, and nefazodone. Benzodiazepines included alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clorazepate, diaze-pam, flurazepam, lorazepam, oxaze-pam, temazepam, and triazolam.

We also determined whether the patient received any mood stabilizer, any antipsychotic, or any antidepressant during the 12-month period. Additional demographic and clinical data on patients who were given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder were collected from the VA National Patient Care Database.

Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the percentage of patients who received at least one medication from each aforementioned drug class. Race was categorized as black or nonblack (defined as white or other race or ethnicity), because relatively few patients (less than 1 percent) were classified as another race or ethnicity. Patients with an unknown race or ethnicity were excluded from the sample (N=368).

We then applied multivariate logistic regression modeling to determine whether differences in the receipt of medication by race remained significant. The analysis controlled for demographic factors, including gender, age, marital status (categorized as married or not married), copayment waiver eligibility, and clinical factors (number of comorbid medical conditions, bipolar subtype, and whether a diagnosis of bipolar disorder was received during an inpatient or outpatient visit). Patients who were eligible for a copayment waiver were considered to have lower income.

The number of medical conditions diagnosed in fiscal year 2001 was based on the clinical classifications of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical conditions included hypertension, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, pancreatitis, thyroid disorders, obesity, hepatitis C, other hepatitis, lower back pain, arthritis, hip problems, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, lung cancer, prostate cancer, skin cancer, spinal cord injury, other accidents or injuries, renal failure, gastric-related disorders, benign prostatic hyperplasia, HIV infection, headache, dementia, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, and anemia.

For the multivariate analyses, we conducted sensitivity analyses of pharmacotherapy class categorizations (for example, excluded clozapine) and independent variables (for example, excluded racial and ethnic groups other than black and white). In all cases, similar results were obtained.

Results

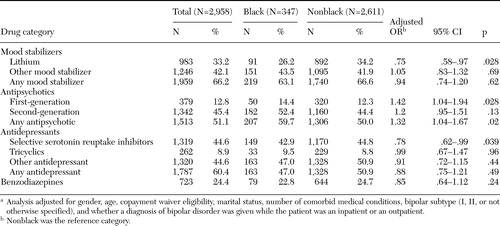

Of the 2,958 patients given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in fiscal year 2001, a total of 347 (11.7 percent) were black, 691 (23.4 percent) were aged 60 years or older (mean±SD age of 52±12 years), and 314 (10.6 percent) were female. Sixty-six percent were given a prescription for any mood stabilizer; 51 percent, any antipsychotic; 60 percent, any antidepressant; and 24 percent, a benzodiazepine. Table 1 lists the overall frequencies of each medication class by total prevalence and by racial group.

Multivariate analyses that adjusted for patient and clinical factors revealed that blacks were less likely than nonblacks to receive lithium and SSRIs (Table 1). However, blacks were more likely than nonblacks to receive first-generation antipsychotics and any antipsychotic. No statistically significant difference was found in the probability of receiving a mood stabilizer other than lithium, any mood stabilizer, second-generation antipsychotics, tricyclics, antidepressants other than SSRIs or tricyclics, any antidepressant, and benzodiazepines.

Discussion

Overall, 66 percent of patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder were given a prescription for any mood stabilizer; 51 percent, any antipsychotic; 60 percent, any antidepressant; and 24 percent, benzodiazepines. After the analysis adjusted for demographic and clinical factors, blacks were more likely than nonblacks to receive first-generation antipsychotics and any antipsychotics. In addition, blacks were less likely than nonblacks to receive lithium and SSRIs.

Our findings on overall mood stabilizer use are similar to previous research among VA patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, which found that among 65,556 veterans, 41 percent were given a prescription for lithium (7). The racial differences that we observed in our study also reflected trends seen elsewhere. For example, among 13,065 patients who received Medicaid, blacks were less likely than whites to be given a prescription for SSRIs (4). Also, in a community-based study on 5,032 patient-visits from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, blacks were less likely than whites to be given a prescription for second-generation antipsychotics (5). However, in our study of patients with bipolar disorder, blacks were no less likely to be prescribed second-generation antipsychotics and were more likely to be prescribed any antipsychotic. Perhaps providers are prone to prescribing antipsychotic medications to black patients because of the perception that black patients are more likely to exhibit psychotic features. Alternatively, in another study of 816 veteran patients, blacks with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder were more likely than whites to receive a concurrent diagnosis of schizophrenia and hence may be more likely to receive antipsychotics (8).

Our results suggest that a substantial proportion of patients with bipolar disorder are receiving other psychotropic medications along with first-line mood stabilizers, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines. The recent concerns about the safety and toxicity of these commonly used psychotropic medications, such as the increased risk of diabetes associated with antipsychotic medications (9) and the possible link between SSRI use and suicidal ideation (10), suggest that careful monitoring of the long-term health risks of psychotropic medication use among patients with bipolar disorder is warranted.

Still, we found that blacks were less likely than nonblacks to be given a prescription for lithium, a medication with substantial research evidence for effectiveness in bipolar disorder that also carries a greater risk of side effects than other mood stabilizers. Blacks were also less likely than nonblacks to receive a prescription for SSRIs, reflecting similar findings (3). In contrast, blacks were more likely than nonblacks to receive a prescription for first-generation antipsychotics, which may also potentially have more extrapyramidal side effects than second-generation antipsychotics. Several reasons for these findings can be proposed. For example, black patients may be more susceptible to the side effects associated with lithium (11) and SSRIs and hence may prefer other medications. In contrast, determinants of racial differences in second-generation antipsychotic use are less clear. Perhaps providers are less willing to switch black patients to second-generation antipsychotics because of perceptions that blacks are less likely to comply with these more expensive medications because of co-occurring substance use (5) or because the providers perceive that the increased risk of metabolic syndromes possibly associated with these medications (9) may disproportionately affect blacks.

Potential limitations of this study include the use of administrative data rather than more formalized diagnostic procedures to identify patients with bipolar disorder, even though we took steps to eliminate diagnoses given to rule out a disorder. In addition, our sample was primarily male, reflecting the VA population. However, a majority of patients with bipolar disorder receive care from publicly funded providers (for example, VA and Medicaid); hence our sample may reflect an indigent population seen within other publicly funded treatment settings.

Conclusions

To our knowledge this is the first population-based study to comprehensively assess racial differences in patterns of medication use among patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Although blacks were less likely than nonblacks to be given prescriptions for lithium and SSRIs, they were more likely to be given a prescription for first-generation antipsychotics and any antipsychotics. Recent concerns about the safety and potential toxicity of these newer psychopharmacologic medications (for example, second-generation antipsychotics and SSRIs) (9,10) suggest that efforts to reduce disparities in access to pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder should be coupled with increased detection and management of the potential side effects of these medications and with efforts by providers to take patient preferences into account.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants IIR-02-283-2 and MRP-022-69 from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service.

Dr. Kilbourne is affiliated with the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion at the Department of Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Mailstop 151C-U, University Drive C, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15240 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Kilbourne is also with the department of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Pincus is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh and the RAND-University of Pittsburgh Health Institute.

|

Table 1. Multivariable analysis for the prescription patterns of psychotropic medication use among 2,958 veterans with bipolar disorder, by racea

a Analysis adjusted for gender, age, copayment waiver eligibility, marital status, number of comorbid medical conditions, bipolar subtype (I, II, or not otherwise specified), and whether a diagnosis of bipolar disorder was given while the patient was an inpatient or an outpatient.

1. Bauer MS, Kirk G, Gavin C, et al: Correlates of functional and economic outcome in bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders 65:231–241,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Medical Practice Project: A State-of-the-Science Report for the Office of the Assistant Secretary for the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Baltimore, Md, Policy Research, 1979Google Scholar

3. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2001. Available at www.mentalhealth.org/cre/toc.aspGoogle Scholar

4. Melfi CA, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, et al: Racial variation in antidepressant treatment in a Medicaid population. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:16–21,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Daumit GL, Crum RM, Guallar E, et al: Outpatient prescriptions for atypical antipsychotics for African Americans, Hispanics, and whites in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:121–128,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, et al: Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:69–71,1992Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Sajatovic M, Blow FC, Ignacio RV, et al: Age-related modifiers of clinical presentation and health service use among veterans with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 55:1014–1021,2004Link, Google Scholar

8. Kilbourne AM, Haas GL, Mulsant B, et al: Concurrent psychiatric diagnoses by age and race among persons with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 55:931–933,2004Link, Google Scholar

9. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North American Association for the Study of Obesity: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:267–272,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA's safety review. British Medical Journal 19:330, 385,2005Google Scholar

11. Strickland TL, Lin KM, Fu P, Anderson D, et al: Comparison of lithium ratio between African-American and Caucasian bipolar patients. Biological Psychiatry 37:325–30,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar