Use of Mental Health Services by Asian Americans

Abstract

This study explored the use of mental health services by Asian Americans and other ethnic populations (N=104,773) in California. The authors used linear regression analyses to assess the role of ethnicity and diagnosis in predicting six-month use of services. East Asians used more services than Southeast Asians, Filipinos, other Asians, Caucasians, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans, even when severity of illness was taken into account. The findings suggest that aggregating Asian subpopulations into a single group in services research is no longer appropriate. Attention needs to be placed on the needs of Southeast Asians and other Asians, whose service use patterns approximate those of the traditionally most underserved groups, African Americans and Latinos.

Early findings on the use of mental health services among Asian Americans indicate underutilization (1,2). Researchers attribute this underutilization to inaccessibility resulting from cultural incompatibility with services and avoidance of care by all but the most severely disturbed individuals (3,4,5). Subsequent research in the 1990s showed more complex patterns, implying progress in the sense that use of outpatient services is higher among Asians than among Caucasians in the United States (4,5).

The study reported here used recent data (1998 to 2002) for a large subsample of Asian Americans (N=10,262) to explore differences in service use between ethnic groups and to determine whether some ethnic groups have more serious conditions than others that account for differences in service use patterns.

Methods

Data collected for statistical purposes were obtained for six counties from the client and service information system of the California Department of Mental Health. A single episode of service was considered for clients aged older than 18 years (N=113,443). Cases with missing information for ethnicity, diagnosis, and gender were removed, resulting in a final sample of 104,773. Approval for the study was obtained from the institutional review board of the University of California, Berkeley.

Three criterion variables, adjusted to six-month utilization rates, were number of outpatient services, number of minutes spent receiving outpatient services, and number of inpatient days. Outpatient services included outpatient therapy, case management, collateral contacts, and medication support. An inpatient service day was defined as a 24-hour inpatient experience in a psychiatric hospital, skilled nursing facility, jail, or adult residential center and could include day services, such as crisis stabilization, or intensive half- or full-day services.

Ethnicity, diagnosis, age, and gender were the independent variables. Ethnicity was organized into nine binary categories: Asian total, East Asians, Southeast Asians, Filipinos, other Asians, Caucasians, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans. The "Asian total" group included East Asians (Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans), Southeast Asians (Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese), Filipinos, and other Asians (Asian Indians, Guamians, Hawaiian Natives, Samoans, and others).

Primary diagnoses were categorized into schizophrenia, major depression, bipolar disorder, and all other disorders (binary coded).

Chi square tests and one-way analyses of variance were conducted with use of SPSS 12.0 for Windows to evaluate differences across ethnic groups. Three three-stage linear regressions, one for each of the utilization criteria, examined variable blocks entered incrementally in the following order: age, gender, and ethnicity (excluding Asian total and with East Asian as the referent, given the focus on Asians' use of services); diagnosis of schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorder (with all other conditions as the referent); and schizophrenia—the most serious condition—by ethnicity interaction terms. This approach involved a total of 19 predictor variables.

Results

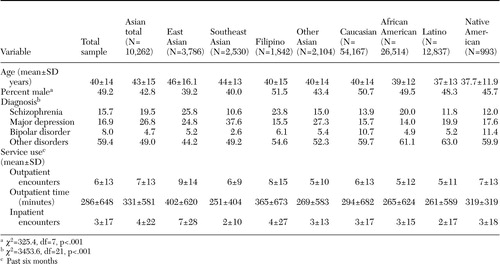

The demographic and service use characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. The most common diagnosis was major depression (14.0 to 37.6 percent), followed by schizophrenia (10.6 to 25.8 percent). Among Filipinos, however, more clients had schizophrenia than depression (23.8 percent and 15.5 percent, respectively); this was also the case for African Americans (20 percent and 14 percent, respectively). Southeast Asian clients had the highest rate of major depression (37.6 percent), and East Asians had the highest rate of schizophrenia (25.8 percent). Diagnoses of bipolar disorder were most prevalent for Native Americans and Caucasians (11.4 percent and 10.7 percent, respectively) and were lowest for Southeast Asians (2.6 percent).

Six-month utilization comparisons indicated that East Asians and Filipinos had the most outpatient encounters (9.1 and 7.7 encounters, respectively), spent the most time in outpatient services (402 and 365 minutes, respectively), and used the most inpatient care (6.7 and 4.4 days, respectively).

The regression models for the three utilization criteria—number of outpatient services, time in outpatient services, and number of inpatient days—were significant (p<.001). (Data from these analyses are available from the first author on request.) The main effects for ethnicity—Filipino, Southeast Asian, other Asians, African American, Latino, Caucasian, or Native American (all significant at p<.001)—indicated that on all three criteria, membership in all ethnic groups, except for Filipino and Native American, was associated with receipt of fewer services than East Asians (referent) after the analysis controlled for demographic characteristics, diagnosis, and the interaction of schizophrenia and ethnicity. The diagnostic main effects were significant (p<.001) in each of the three models, indicating that individuals with major mental disorders received more services of all types than individuals with other disorders after other factors had been taken into account.

The interaction terms for schizophrenia and ethnic group with respect to inpatient days were all significant (p<.001), indicating that, after all other factors had been taken into account, people with schizophrenia and membership in any other ethnic group were likely to receive less inpatient care than East Asians with schizophrenia. The same was true of outpatient services, except in the case of Filipinos and Native Americans. Less significant results were observed for Latinos (p=.019) and Caucasians (p=.048). With respect to the amount of time spent in outpatient services, the interaction terms for schizophrenia and ethnic group were significant only in the case of Southeast Asians (p=.003), other Asians (p=.005), and Caucasians (p=.020), indicating that these persons with schizophrenia spend less time in outpatient services compared with East Asians who have schizophrenia.

Discussion

Our results are consistent with the trend of reports of increased inpatient and outpatient service use among Asian Americans and suggest a more complex pattern of service use than previously reported. Given the observed utilization reported among Asian subpopulations, future research using the Asian and Pacific Islander aggregation seems inappropriate in that utilization experiences of Asian subpopulations vary significantly.

We found the highest number of patients with schizophrenia in the East Asian subgroup, which supports previous research indicating that Asians use services when they have very severe conditions. However, this finding remained significant in our study after we controlled for the presence of severe mental disorders and the interaction of schizophrenia with ethnicity, indicating that changes have occurred in the overall acceptance of mental health services among East Asians in California that are independent of severity of illness.

Our results cannot directly speak to the issue of acculturation, a hypothesis about differences in utilization patterns that is frequently cited in the literature, other than to note that the Asian-American subpopulations that demonstrated underutilization are those who are historically more recent arrivals. There is also the more general finding worldwide (6) and across ethnic groups (7,8) that use of specialty mental health services is related to education, perhaps itself an indicator of acculturation. Our results are consistent with the notion that lower educational attainment inhibits the use of mental health services—census statistics (9) show that the educational attainments of Southeast Asians are significantly less than those of East Asians and Filipinos.

We view this association less as an individual effect (many persons with severe mental illness do not have high educational attainment) and more as a context effect similar to that observed by Chow and colleagues (10), in which the characteristics of poverty areas moderate the relationship between race or ethnicity and use of mental health services. We assume that the higher levels of educational attainment that have been achieved in some Asian subpopulations have been accompanied by increasing socioeconomic status and an environment that is more supportive of using mental health services. In fact, indicators of educational attainment (the percentages of the county population that graduated from high school and from college) that were added to our regression models in a fourth block were significantly associated with increased service use for each of the three criteria (p<.001 for all six coefficients).

Limitations of this study stem from the quality of the administrative data set. Data on important demographic variables—education (only 28 percent reported), income, and marital status—were not available, nor was information on English proficiency, level of acculturation, and severity of symptoms.

Conclusions

This study showed that East Asians make more extensive use of public mental health services in California than do members of other ethnic subpopulations. Although this high utilization rate was attributable to some extent to the severity of this subgroup's illnesses, the finding was significant even after diagnosis was taken into account. Thus aggregating Asian subpopulations in mental health services research no longer seems appropriate. More attention needs to be placed on the needs of Southeast Asians and other Asian subpopulations whose utilization patterns approximate those of the traditionally most underserved groups, African Americans and Latinos.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant RO1-MH-37310 and training grant HH-18828 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the School of Social Welfare of the University of California, Berkeley, and with the Mental Health and Social Welfare Research Group in Berkeley. Send correspondence to Dr. Barreto at 120 Haviland Hall, UC Berkeley, Berkeley, California 94720-7400 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic and service use characteristics of a sample of Asians and other ethnic groups (N=104,773) in California

1. Uba L: Asian Americans: Personality Patterns, Identity, and Mental Health. New York, Guilford, 1994Google Scholar

2. Leong FTL: Counseling and psychotherapy with Asian Americans: review of the literature. Journal of Counseling Psychology 33:196–206,1986Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2001Google Scholar

4. Sue S: Asian American mental health: what we know and what we don't know, in International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, 14th Aug 1998. Edited by Lonner WJ, Dinnel DL. Bellingham, Wa, Western Washington University, 1999Google Scholar

5. Akutsu P: Mental health care delivery to Asian Americans: review of the literature, in Working With Asian Americans: A Guide for Clinicians. Edited by Lee E. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

6. Have M, Oldehinkel A, Vollebergh W, et al: Does educational background explain inequalities in care and service use for mental health problems in the Dutch general population? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 107:178–187,2003Google Scholar

7. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al: Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:928–934,1999Link, Google Scholar

8. Barney D: Use of mental health services by American Indian and Alaska Native elders. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research 5:1–14,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Niedzwiecki M, Duong TC: Southeast Asian American Statistical Profile. Washington, DC, South East Asian Resource Action Center (SEARAC), 2004Google Scholar

10. Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L: Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. American Journal of Public Health 93:792–797,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar