Involvement With the Criminal Justice System Among New Clients at Outpatient Mental Health Agencies

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed involvement with the criminal justice system among new clients of community mental health centers and self-help agencies in order to determine the characteristics and service needs of this population. Such information has implications for improving the care available for persons with mental illness who have been involved with the criminal justice system. METHODS: Interview assessments and criminal records were obtained for 673 new clients of 21 outpatient mental health agencies. Descriptive statistics, chi square tests, and multivariate analysis of variance were used to describe these new help-seekers and their involvement with the criminal justice system. RESULTS: A total of 303 study participants (45 percent) had at least one contact with the criminal justice system before arriving at the agency, with an approximately equal percentage at community mental health centers and self-help agencies. The mean±SD number of contacts with the criminal justice system was 7.81±9.12. A total of 240 individuals (36 percent) had at least one criminal conviction, including 128 (19 percent) with a felony conviction. Common charges and convictions included petty theft, assault and battery, felony theft, narcotics offenses, and misdemeanor drug offenses. Clients who had been involved with the criminal justice system were more likely to be homeless, to have drug dependence, to have greater psychological disability, and to have less personal empowerment than other clients. CONCLUSIONS: The population overlap between the mental health system and criminal justice system and the multiple problems facing criminally involved clients argues for greater collaboration between the two systems and a comprehensive package of services to meet the multiple needs of this population. The equal distribution of these individuals and similar offense patterns at both types of agencies necessitates further consideration of the role that nontraditional service providers have in serving individuals with a history of involvement with the criminal justice system

Currently more persons with mental illness are living in the community than at any other time in the postinstitutional era (1). A large proportion of these individuals have multiple problems, including mental illness, substance abuse or dependence, social and behavioral problems, and involvement with the criminal justice system (2). Moreover, persons with mental disorders are often members of groups that have a high risk of criminal arrest—for example, substance users, the unemployed, the less educated, the homeless, and those with a lower income (3,4). Not surprisingly then, previous researchers have estimated that as many as 40 to 50 percent of clients in the community mental health system might have a history of criminal arrest (5,6,7).

Despite such sizable estimations, there has been a relative dearth of research focused on involvement with the criminal justice system among clients of the outpatient mental health system. Instead, research on the relationship between the mental health and criminal justice systems has traditionally used criminal justice populations to assess mental health services for prisoners (8,9), community-based care of released mentally ill offenders (10,11,12,13,14,15), and the hypothesized criminalization of the mentally ill, which has been addressed by counting arrested and incarcerated individuals with mental disorders (16,17,18,19).

However, two characteristics of these studies limit their utility for understanding new community mental health patients who have been involved with the criminal justice system. First, studies of former inmates may not be representative of most people who are involved with the criminal justice system and who also have mental health care needs. Those who are on probation or parole have been convicted, but the incidence of arrest is far more common than conviction (5). Individuals with mental illness, if they are charged at all, are most often charged with misdemeanors and avoid incarceration (20). Second, outpatient treatment offered to released offenders is different from that provided to other groups (13). For the latter, treatment focuses on the alleviation of symptoms. For persons on probation or parole, treatment may be a required condition of release, their behavior is closely monitored, mental health agencies may provide compliance reports to probation or parole officers (13), staff may use threats to improve treatment compliance (6,21), and mental health workers may monitor illegal behavior, thus becoming de facto agents of the criminal justice system (21).

This study fills a gap in the previous research by describing characteristics and involvement with the criminal justice system among new clients of the community mental health system. Among studies with a similar focus, most are older or offer little perspective on community mental health outpatients because of overly restrictive or inclusive samples. Harry and Steadman (22) followed a sample of new arrivals at a community mental health clinic for several years and noted that this group had higher arrest rates than the general population, although their rates were lower than those of former patients of state mental hospitals. Holcomb and Ahr (23), studying 611 young adults in public inpatient, outpatient, and community residential care during 1982, found that patients with a diagnosis of drug or alcohol abuse had the most criminal justice system complications, including the greatest number of arrests and probation or parole violations.

In related yet more narrowly focused studies, Draine and Solomon (7) found that 42 percent of intensive case management clients at one community mental health agency had a history of arrest. Lafayette and colleagues (24) found that 59 percent of outpatients with schizophrenia had a history of arrest, and McGuire and Rosenheck (25) found that two-thirds of people entering an assertive community treatment case management program had a history of incarceration. This latter study also found that among homeless persons with mental illness, those with a history of incarceration had more serious problems than those without such a history.

In studying outpatient mental health care, it is also important to account for recent changes in the delivery of community-based services. Although the community mental health center has long been the traditional provider of outpatient care, alternative sources of care, especially mental health self-help agencies, have become increasingly common. As a result, to fully understand involvement with the criminal justice system among clients of outpatient mental health agencies, one must consider users of both traditional and nontraditional mental health service providers. To our knowledge, no studies have described such involvement among users of self-help agencies such as those included in this study.

This study therefore addressed three questions. First, what are the criminal justice system involvements of new clients of outpatient mental health agencies? Second, how do clients who have been involved with the criminal justice system differ from other clients? Third, are observed differences consistent across different types of mental health agencies—in particular, between self-help and community mental agency settings?

Methods

Sample

Study participants were recruited from 21 agencies located in six counties in Northern California. Eleven self-help agencies were paired with ten community mental health centers (one was paired with two self-help agencies) on the basis of their proximity to each other (median distance of 2.5 miles between pairs). This close proximity allowed for comparisons of service use by a single local population with access to both types of agency.

Between 1996 and 2000, a total of 787 adult "new users"—that is, individuals who were new to the organization or similar organizations for at least six months before their arrival—were asked to participate in the study; 673 agreed, and 114 refused (a 14 percent refusal rate, the same in both self-help agencies and community mental health agencies, with no significant demographic differences between groups). The final sample included 226 persons recruited from self-help agencies (34 percent of the sample) and 447 from community mental health agencies (66 percent). Institutional review board approval and informed consent were obtained before any data were collected.

The community mental health agencies were professionally run county agencies specializing in assessment, medication review, therapy, and case management (26). The self-help agencies had "a client director, a governing board with a majority of client members, and an organization structure where clients hire and fire staff—including employed professionals" (26). Self-help agencies, emphasizing mutual support and peer-driven services, represent a new and alternative source of community-based care (26,27).

Assessment

Complete criminal justice records for all study participants were obtained from the California Department of Justice. Each criminal record is a complete summary of each contact, criminal charge, conviction, and sentence that the individual has experienced. A criminal contact is defined as any recorded incident of criminal arrest, detention, or citation. Study participants were identified as being involved with the criminal justice system if they had at least one such contact at any time before enrollment in the study.

The summary variables derived from the criminal records (described below) were defined by guidelines of the California Department of Justice (28) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) (29). California defines violent offenses to include homicide, forcible rape, robbery, felony assault, and kidnapping. Property offenses include burglary, felony theft, motor vehicle theft, forgery, crimes involving checks and access cards, and arson. Drug offenses include narcotics involvement, marijuana felonies, dangerous drug offenses, and other drug felonies. Likewise, consistent with the FBI's definition, index offenses, used as an important measure of crime in the United States, are homicide, forcible rape, robbery, assault, burglary, theft, and motor vehicle theft.

Because plea bargains and legal maneuvering that occur after the initial contact with the criminal justice system are not explicitly stated on an individual's record, it should be noted that a discussion of charges pertains only to charges that were pressed at the time of arrest. Furthermore, according to the California Department of Justice, "jail" is defined as a city or county facility used for detaining both sentenced and unsentenced people (28). However, in the study reported here, references to jail sentences refer only to individuals who were sentenced to jail after being convicted for a crime. Prisons, on the other hand, are defined as state-operated correctional facilities reserved for felons who have received sentences of at least one year's duration.

Interview schedules were used to gather information about demographic characteristics, housing, income, attitudes, empowerment, functional and clinical status, and diagnoses. Internal consistencies for all standardized scales were assessed by using Cronbach's alpha.

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) measures an individual's level of psychiatric disability (30). Possible scores range from 24 to 168, with higher scores indicating more severe psychiatric symptoms (alpha=.84). The Centers for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale yields scores from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater depression (31) (alpha=.8). The Health Problems Checklist counts the presence of 35 different physical health problems, with higher scores showing greater physical health problems (32) (alpha=.85). Scores on the Independent Social Functioning Scale (ISFS) range from 75 to 336, with higher scores indicating better social functioning (33) (alpha=.95). Scores on the Assisted Social Functioning Scale (ASFS) range from 36 to 180, with higher scores indicating better social functioning (34) (alpha=.98). Social functioning refers to one's willingness to participate in community-based activities; the ease with which one makes social contacts; contact with family, friends, and acquaintances; and involvement in work or shopping activities (35). Scores on the Personal Empowerment Scale range from 26 to 83, with higher scores indicating a greater sense of feeling empowered (36) (alpha=.78). Personal empowerment is conceptualized as the amount of choice, control, and freedom one feels in leading his or her life. Scores on the Hope Scale range from 0 to 50, with higher scores representing greater hope (37) (alpha=.75). Scores on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale range from 10 to 50, with higher scores representing greater self-esteem (38) (alpha=.77). Scores on the Locus of Control Scale range from 18 to 49, with higher scores indicating greater internal locus of control (39) (alpha=.63).

A final scale counted the number of services that respondents reported using during the six months before the baseline interview. The scale used in this study is a modified version of the Comprehensive Service Use Scale (40), including 37 support, advocacy, vocational, housing, health care, social activity, and counseling services from the original scale plus two additional services—help in finding volunteer work and visiting an alternative medicine specialist. All these services may have been provided by a variety of formal service providers, including community mental health centers, self-help agencies, social service agencies, and other formal agency providers. Scores range from 0 to 39, with higher scores showing greater service use (alpha=.88).

Diagnosis was assessed with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule-IV. Interviewers were trained by the Center for Self-Help Research in Berkeley, California.

Data analyses

Descriptive data and characteristics of criminal involvement are presented in percentages for categorical variables and means with standard deviations for all continuous measures. Furthermore, differences in housing status, primary psychiatric diagnosis, and substance dependence between study participants who had been involved with the criminal justice system and those who had not were assessed by using Pearson's chi square statistics.

Differences in measures of psychosocial functioning, health, empowerment, and past service use were assessed by using a single SPSS/GLM multivariate analysis of variance procedure. All dependent variables were tested for normality and all yielded acceptable skewness and kurtosis values for inclusion in this test (41): for the BPRS, .901 (skewness) and .444 (kurtosis); for the CES-D, .059 and -.697; for the ISI, -.063 and .032; for the ASI, .543 and -.477; for the Personal Empowerment Scale, -.124 and -.162; for the Hope Scale, 1.00 and -.385; for the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, -.281 and -.151; for the Locus of Control Scale, .021 and -.183; for the Health Problems Checklist, 1.08 and 1.66; and for the Comprehensive Service Use Scale, 1.03 and 1.16. Any participant for whom data were missing on any of the dependent variables was excluded. This approach excluded 35 people, leaving a total sample of 638 for this test. Differences in mean scale scores were considered significant at the .05 level after a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Results

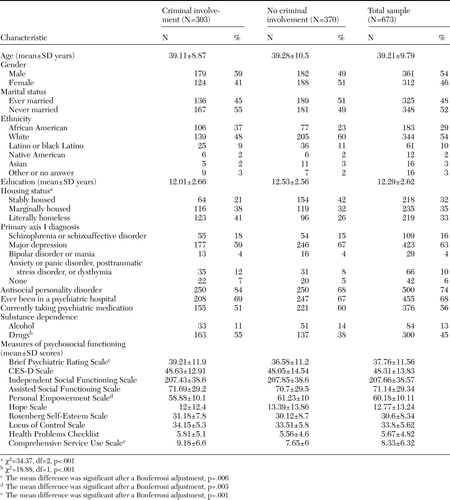

Among 673 new users of outpatient mental health agencies, 303 (45 percent) had at least one contact with the criminal justice system before their arrival at the agency, including 204 clients of community mental health centers (46 percent of the community mental health center sample) and 99 clients of self-help agencies (44 percent of the self-help agency sample). Preliminary analyses (data not shown) indicated no differences across agency setting on criminal involvement or demographic measures. There was also no interaction between agency and the respondent's county of enrollment in the study. Thus comparisons between those who had been involved with the criminal justice system and those who had not without regard for agency interaction or county were possible. Such comparisons are presented in Table 1. On the basis of chi square analyses, the criminally involved participants were more likely to be literally homeless—living in their car, on the streets, or in a shelter—and less likely to be stably housed. They were also more likely to be drug dependent. No difference was noted in primary psychiatric diagnosis or alcohol dependence.

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) (N=638) made comparisons based on the ten measures of psychosocial functioning (Table 1). This procedure may be considered robust on the basis of Box's test of equality of covariance matrices (p=.444) (42). The main effect for involvement with the criminal justice system was significant (Wilks' lambda=.951, F=3.26, df=10, 627, p< .001). This MANOVA showed that criminally involved individuals had greater psychological disability and less personal empowerment. The participants who had criminal justice system involvement also used a greater variety of services during the six months before joining the study.

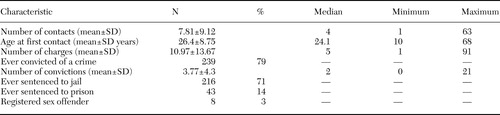

As shown on Table 2, people who had been involved with the criminal justice system had, on average, experienced approximately eight contacts and four convictions before their arrival at the agency. The mean age at first contact was 26.4 years, or almost 13 years before study enrollment. The vast majority of the criminally involved sample (79 percent) had been convicted of at least one crime. Among persons who had been convicted of a crime, 23 (10 percent) had been convicted of a felony only, 111 (46 percent) had been convicted of a misdemeanor only, and 105 (44 percent) had been convicted of both. Among persons who had been involved with the criminal justice system, a considerably higher number had been sentenced to jail than to prison (71 percent compared with 14 percent). For the entire study sample of 673 persons, 32 percent had been sentenced to jail, compared with only 6 percent who had ever served time in prison.

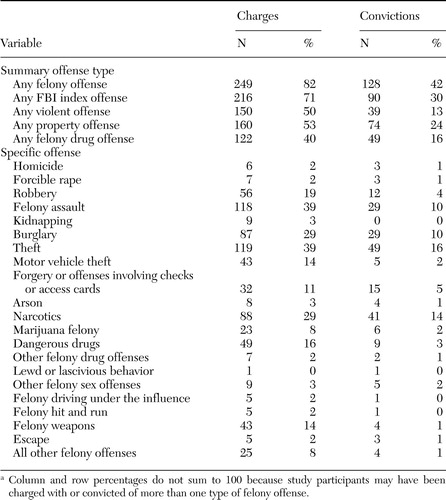

Data on felony charges and convictions are presented in Table 3. A majority of the persons who had been involved with the criminal justice system had faced at least one felony charge (82 percent). The percentage of clients who had been charged with an index offense was equally high (71 percent). Among felony charges, property offenses were the most common (53 percent). The percentage of clients who faced violent offense charges was also high (50 percent), although the number of convictions (13 percent) was far lower than for property offenses (24 percent) and drug offenses (16 percent). The most common offense for both charge (39 percent) and conviction (16 percent) was theft, followed by narcotics (29 percent charged and 14 percent convicted).

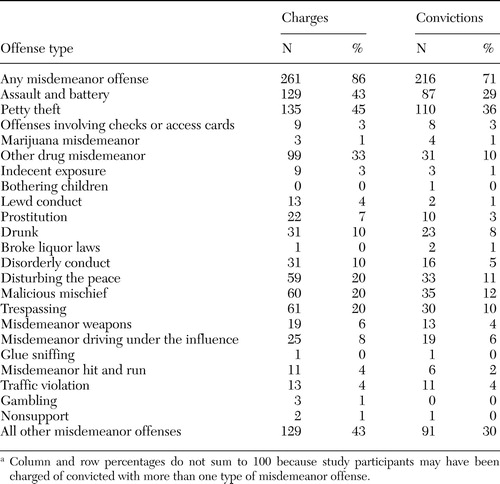

Data for misdemeanor charges and convictions are presented in Table 4. Some of the more common types of misdemeanor offenses were assault and battery (43 percent charged and 29 percent convicted), petty theft (45 percent charged and 36 percent convicted), drug offenses (33 percent charged and 10 percent convicted), and trespassing (20 percent charged and 10 percent convicted).

Discussion

Perhaps the most substantial findings of this study were that almost half the sample had had at least one contact with the criminal justice system before arrival at the agency; four-fifths of those with such contact had been charged with a felony and almost half had been charged with a violent felony offense. Although the percentage of clients with a history of involvement with the criminal justice system and the percentage charged with a felony are consistent with findings reported in other studies of mental health populations (5,7,23), the percentage of clients charged with an index offense was considerably higher than figures reported for other high-risk populations. For example, compared with the 71 percent of criminally involved clients charged with an index offense in this study, studies of crime participation among urban males—often considered one of society's most dangerous and troublesome groups—have estimated that 25 to 35 percent will be arrested for an index offense in their lifetime (43). The percentages of clients charged with felony and index offenses contrast markedly with those in studies reporting that mentally ill individuals are most often charged with misdemeanor offenses (20). In this study, criminally involved clients had faced the full range of misdemeanor, felony, and index offense charges.

Although conventional thinking might conclude that such findings are further proof that persons with mental illness are being criminalized, the results of this study offer only limited support for this conclusion. Consistent with the criminalization hypothesis, a large percentage of the mental health system clients in this sample had been involved with the criminal justice system. However, these data cannot establish the cause-and-effect link between mental illness and crime needed to truly support the criminalization argument. Instead, the study results seem to provide stronger support for the role of social disadvantage in crime as described by Draine and colleagues (3). In this scenario, poverty and its related factors, such as unemployment and substance abuse, moderate the relationship between crime and serious mental illness. Given the myriad of problems facing criminally involved people in this study—including homelessness, drug dependence, and psychological impairment—one might reasonably assume an exceptional level of involvement with the criminal justice system, especially for charges of theft, trespassing, disturbing the peace, and general misdemeanor crimes. These types of offenses seem to be closely associated with the multiple problems listed above.

More generally, the results of this study indicate that there is an interaction between the community mental health system and the criminal justice system. This interaction is by no means a new finding in the research literature. However, this is the first study to document such an interaction at both traditional and nontraditional community mental health settings. Alternative service providers, such as the self-help agencies in this study, appear to serve a comparable proportion of criminally involved clients as their more traditional counterparts. Furthermore, problems such as homelessness and drug dependence were consistent among the criminally involved clients across agency settings. Because self-help agencies often serve persons who underutilize or are underserved by conventional community mental health centers (40), such agencies may be an important source of care for individuals with histories of involvement with the criminal justice system and mental health needs. Future research should assess service use and outcomes for such clients.

California differs from many other states in terms of the degree of urbanization and the level of public support for the mental health and criminal justice systems (23). Thus caution must be used in assuming that the results of this study are generalizable to all other states and sites. In addition, only California's criminal justice records were used, and it is possible that criminal involvements in other states did not appear on these records.

Conclusions

The outpatient mental health system appears to be at least as saturated with criminally involved individuals as the criminal justice system is with mentally ill individuals—if not more so. Significant numbers of these individuals have multiple problems and index crime offenses. This multitude of needs, compounded by the undeniable overlap between the two systems, necessitates consideration of the full scope of available services and service providers to care for this population. Although research should continue to assess the role of traditional service providers to treat persons who have been involved with the criminal justice system, effort should also be made to evaluate other community resources, including alternative service providers and self-help agencies.

Dr. Theriot is affiliated with the College of Social Work at the University of Tennessee, 1618 Cumberland Avenue, 322 Henson Hall, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996-3333 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Segal is with the School of Social Welfare at the University of California at Berkeley.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics, housing status, psychiatric and substance dependence diagnoses, and measures of psychosocial functioning in a sample of 673 new clients of outpatient mental health agencies who had been involved with the criminal justice system and those who had not

|

Table 2. Involvement with the criminal justice system in a sample of 303 clients of outpatient mental health agencies who had had contact with the criminal justice system

|

Table 3. Felony offense charges and convictions in a sample of 303 clients of outpatient mental health agencies who had been involved with the criminal justice systema

a Column and row percentages do not sum to 100 because study participants may have been charged with or convicted of more than one type of felony offense.

|

Table 4. Misdemeanor offense charges and convictions for 303 clients of outpatient mental health agencies who had been involved with the criminal justice system

1. Teplin LA: The criminalization of the mentally ill: speculation in search of data. Psychological Bulletin 94:54–67, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Wilson D, Tien G, Eaves D: Increasing the community tenure of mentally disordered offenders: an assertive case management program. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 18:61–69, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, et al: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with a serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565–573, 2002Link, Google Scholar

4. Martell DA, Rosner R, Harmon RB: Base-rate estimates of criminal behavior by homeless mentally ill persons in New York City. Psychiatric Services 46:596–601, 1995Link, Google Scholar

5. McFarland BH, Faulkner LR, Bloom JD, et al: Chronic mental illness and the criminal justice system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:718–723, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Solomon P: Response to "A model program for the treatment of mentally ill offenders in the community." Community Mental Health Journal 35:473–475, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Draine J, Solomon P: Comparison of seriously mentally ill case management clients with and without arrest histories. Journal of Psychiatry and the Law 20:335–342, 1992Google Scholar

8. Ditton P: Mental Health Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC, United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999. Available at www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjsGoogle Scholar

9. Goldstrom ID, Henderson M, Male A, et al: Jail mental health services: a national survey, in Mental Health, United States, 1998. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson M. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1998Google Scholar

10. Solomon P, Draine J: Explaining lifetime criminal arrests among clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 27:239–251, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

11. Solomon P, Draine J, Marcus SC: Predicting incarceration of clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Psychiatric Services 53:50–56, 2002Link, Google Scholar

12. Solomon P, Draine J: Jail recidivism in a forensic case management program. Health and Social Work 20:167–173, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, Gross BH: Community treatment of severely mentally ill offenders under the jurisdiction of the criminal justice system: a review. Psychiatric Services 50:907–913, 1999Link, Google Scholar

14. Ventura LA, Cassel CA, Jacoby JE, et al: Case management and recidivism of mentally ill persons released from jail. Psychiatric Services 49:1330–1337, 1998Link, Google Scholar

15. Clark RE, Ricketts SK, McHugo GJ: Legal system involvement and costs for persons in treatment for severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 50:641–647, 1999Link, Google Scholar

16. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women: pretrial jail detainees. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:505–512, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Teplin LA: The prevalence of severe mental disorder among male urban jail detainees: comparison with the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. American Journal of Public Health 80:663–669, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Guy E, Platt JJ, Zwerling I, et al: Mental health status of prisoners in an urban jail. Criminal Justice and Behavior 12:29–53, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Swank GE, Winer D: Occurrence of psychiatric disorder in a county jail population. American Journal of Psychiatry 133:1331–1333, 1976Link, Google Scholar

20. Schnapp WB, Cannedy R: Offenders with mental illness: mental health and criminal justice best practices. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 25:463–466, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Draine J, Solomon P: Threats of incarceration in a psychiatric probation and parole service. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 71:262–267, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Harry B, Steadman HJ: Arrest rates of patients treated at a community mental health center. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:862–866, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Holcomb WR, Ahr PR: Arrest rates among young adult psychiatric patients treated in inpatient and outpatient settings. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:52–57, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Lafayette JM, Frankle WG, Pollock A, et al: Clinical characteristics, cognitive functioning, and criminal histories of outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 54:1635–1640, 2003Link, Google Scholar

25. McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA: Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:42–48, 2004Link, Google Scholar

26. Segal SP, Hardiman ER, Hodges JQ: Characteristics of new clients at self-help and community mental health agencies in geographic proximity. Psychiatric Services 53:1145–1152, 2002Link, Google Scholar

27. Segal SP, Silverman CJ, Temkin T: Characteristics and service use of long-term members of self-help agencies for mental health clients. Psychiatric Services 46:269–274, 1995Link, Google Scholar

28. Crime and Delinquency in California, 2001. Sacramento, Calif, State of California Office of the Attorney General, Department of Justice, Division of California Justice Information Services, Criminal Justice Statistics Center, 2002Google Scholar

29. Crime in the United States, 2001: Uniform Crime Reports. Washington, DC, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Available at www.fbi.gov, 2002Google Scholar

30. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385–401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Segal SP, Gomory T, Silverman CJ: Health status of homeless and marginally housed users of mental health self-help agencies. Health and Social Work 23:45–52, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Segal SP, Aviram U: The Mentally Ill in Community-Based Sheltered Care. New York, Wiley, 1978Google Scholar

34. Segal SP, Kotler PL: Personal outcomes and sheltered care residence: ten years later. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 63:80–91, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Segal SP, Hodges JQ, Hardiman ER: Factors in decisions to seek help from self-help and co-located community mental health agencies. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 72:241–249, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Segal SP, Silverman CJ, Temkin T: Measuring empowerment in client-run self-help agencies. Community Mental Health Journal 31:215–227, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Zimmerman M: Toward a theory of learned hopefulness: a structural model analysis of participation and empowerment. Journal of Research in Personality 24:71–86, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Rosenberg M: Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1965Google Scholar

39. Dutteiler PC: The Internal Control Index: a newly developed measure of locus of control. Educational Psychological Measurement 44:209–221, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Theriot MT, Segal SP, Cowsert MJ Jr: African-Americans and comprehensive service use. Community Mental Health Journal 39:225–237, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. George D, Mallery P: SPSS for Windows Step By Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 10.0 update. Boston, Allyn and Bacon, 2001Google Scholar

42. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd ed. New York, Harper Collins College Publishers, 1996Google Scholar

43. Blumstein A, Cohen J, Roth JA, et al: Criminal Careers and "Career Criminals," vol 1. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1996Google Scholar