The Cornell Service Index as a Measure of Health Service Use

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This article describes the development, administration, and reliability of the Cornell Services Index (CSI), a new instrument that measures health service use. The CSI was developed to create a standardized measure of the quantity and characteristics (for example, site and provider) of services used by adults. Descriptive data are provided to illustrate the application of the CSI in a community sample of adults who were newly admitted to outpatient mental health clinics. These data provide information about the pathways to care. METHODS: The interrater and test-retest reliability of the CSI were evaluated by using a sample of 40 adults who were seeking mental health treatment. Descriptive data on service use in a sample of 1,279 adults seeking care in outpatient mental health clinics was provided to demonstrate the application of the CSI. RESULTS: The CSI is a portable, easy to use, and brief assessment of service use. It has good interrater and test-retest reliability among adults without cognitive impairment. In the three months before seeking care, 31 percent of the adults interviewed had made a mental health visit, 36 percent had been hospitalized, and more than half (59 percent) had made a medical visit. Twenty-three percent of adults had sought care from a hospital's emergency department. CONCLUSIONS: The CSI is a reliable method to assess health service use for adults. The measure can extend assessment of use beyond the traditional mental health service use questions and provide a snapshot of service use patterns across types, providers, and sites of service among adults who seek mental health care.

The President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health was designed to address the evidence that demonstrates that persons with psychiatric illnesses who need care underuse mental health services (1). Increased awareness of mental health needs has expanded the array of available services and settings that provide care. As the mental health field moves toward improving access and identifying efficacious and cost-effective models of care, researchers have begun to examine links between service use and clinical outcomes. More information on the types of services received, the settings in which they are delivered, and the disciplines of providers could advance the study of the relationships between service use, course of illness, and outcomes of specific mental disorders.

To examine these relationships there is a need for a measure that provides sensitive, detailed, and reliable means of classifying the various domains of mental health services used by adults. In this article we describe the development, administration, and reliability of the Cornell Services Index (CSI). To illustrate the use of the CSI we report on descriptive data generated from a community sample of persons who were seeking outpatient mental health treatment. These data illustrate the use of the instrument.

Instrument development

The CSI was developed to document the quantity and type (for example, site and provider) of services used by adults who were seeking treatment in mental health clinics in Westchester County, New York, as part of a study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. The instrument was designed to be a portable, brief method of documenting the services used.

Before creating the CSI, the investigators reviewed the literature to identify measures used in large-scale studies with adults, but they were unable to find an easily administered measure to classify services in sufficient detail. The Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study questions served as the foundation for the CSI (2). To increase the accuracy of reported information the instrument focused on service use in the past three months, rather than use in the past six months, the period used in the ECA study. Psychological service options were expanded from the ECA study by using the services catalogued by the 1990 Client Sample Survey of Outpatient Programs (3). In order to reflect the aging of the population and the investigators' interest in geriatric clinical mental health service use, questions from the Service Utilization Instrument (SUI) were incorporated to assess services used by disabled or frail geriatric patients—for example, personal aides, transportation assistance, and home meal delivery. The SUI has been widely used to assess service use in older populations, including community-dwelling older adults (4), adult day care populations (5), and medically underserved individuals with diabetes (6). The grid format of the SUI, which allows for the recording of detailed information for each service, was used as a basis for the development of the CSI.

Since the development of the CSI, a review of the measures used in large-scale clinical trials found that Rosenheck and colleagues (7) at Yale University developed the Service Use and Resources Form (SURF). The SURF is a multi-item record of service use that can be completed by an informant. Like the CSI, the SURF covers a broad range of services and gathers information about the site of service. Unlike the CSI, it includes others resources consumed but does not include the discipline of the provider (7).

Following the development of the CSI, the test-retest and interrater reliability of the scale were examined. Application of the CSI was conducted in a sample of adults who were seeking mental health care at outpatient clinics in Westchester County.

Methods

Domains

The CSI was developed to assess the frequency and duration of use of a range of services over the past three months. Services were aggregated into four types: outpatient psychiatric or psychological, outpatient medical, professional support, and intensive services. Outpatient psychiatric or psychological services include psychotropic medication visits, psychotherapy, diagnostic evaluations, drug and alcohol counseling, and self-help groups. Outpatient medical services include all visits to medical or other providers, including primary care visits and physical therapy. Professional support services include service visits made to the home, ranging from visits by a home health nurse to meal delivery service. Intensive services are distinguished from outpatient visits to indicate either emergent and unplanned service visits (for example, crisis team visit and emergency department visits) or longer-term intensive services, such as inpatient hospitalization and inpatient rehabilitation programs.

For each service use visit, certain items are coded: the discipline of the primary provider (for example, psychiatrist, social worker, or clergy), the location of the service (for example, mental health or medical clinic), and the reason for the service (for example, new medical problem or mental health issue). Finally, the CSI records the out-of-pocket cost to the individual and the primary method of payment (for example, Medicare, Medicaid, or self-pay).

Once the data are collected, aggregate or individual services used can be described as whether or not they occurred (a dichotomous variable) or as a measure of service use intensity (the sum of visits made). The service characteristics (for example, provider and site) of services used can be examined within individual or aggregate service categories. The CSI form can accommodate multiple visits of the same type that may have different providers or settings. The CSI is available from the first author.

Administration

A bachelor's-level research interviewer who receives training can administer the CSI. Training is initiated through familiarization with the service use options and recording procedure; in-person supervision was used to train each interviewer to administer the CSI. The training includes a review of the services that are available in the community and specific examples of service sites and providers. Raters are taught to help interviewees establish the three-month reference period by using holidays or personal events to define the assessment period. Once trained on the CSI, interviewers conduct independent assessments. The CSI manual provides guidelines for scoring. Most CSI interviews take between three and five minutes.

Interrater reliability

Interrater reliability between the three raters and test-retest reliability were examined with a sample of 40 adult participants. In each administration, one bachelor's-level trained research assistant administered the CSI while the other two raters observed and scored the responses. Interrater reliability was examined at both the item and the aggregate scale level.

To examine agreement at the scale level all items were transformed into z-scores, and then an aggregate scale score was calculated. By using a random effects model, intraclass correlation coefficients were computed across the three raters for the five aggregates scales examined. Agreement across raters for binary data was examined by using kappa statistics and positive, negative, and overall agreement. Agreement across raters for the categorical items was examined by calculating the percentage of congruence among the three raters.

Test-retest reliability

Test-retest analyses were performed with a sample of 40 individuals who were interviewed with the CSI at two time points that were two weeks apart. To calculate reliability Pearson correlations were computed for the continuous items and for the scales; phi coefficients were computed for dichotomous variables.

Application in a community sample

To test the administration and usefulness of the CSI, a sample of persons newly admitted to nine mental health clinics in Westchester County were interviewed with the CSI. The data were part of a screen for a larger study on the course and outcomes of major depression in the community (8,9). Participating clinics were selected by consulting with the Commissioner of Mental Health in order to maximize socioeconomic and ethnic diversity. Westchester County has approximately 923,459 inhabitants residing in urban, semiurban, suburban, and semirural settings and includes Yonkers, the third largest city in New York State. The ethnic breakdown of the population of Westchester County is similar to the U.S. distribution, with slightly greater representation from racial and ethnic minority groups (14.0 percent blacks and 15.6 percent Hispanics) (10). Clinic administrators assisted the study by providing intake interview schedules and clinic space to conduct interviews. Interviews were conducted at the service sites.

Participants. English-speaking individuals 18 years and older who were consecutively admitted to the participating mental health clinics from October 1995 to December 1997 were eligible for the study. The institutional review board of Weill Cornell approved the study protocol and procedures. New admissions were approached, study procedures were explained fully, and written informed consent was obtained from interested adults before screening. A majority of new patients (1,397 of 1,515 patients, or 92 percent) agreed to be interviewed. Consenting patients were screened for cognitive impairment (defined as either a diagnosis of dementia or a Mini Mental State Examination score less than 24) (11). The 1,279 adults who were not impaired were administered the CSI and a demographic questionnaire.

Data analyses. To examine patterns of service use we examined the likelihood of making a visit, the average number of visits and the average number of hospital-days, and, where applicable, the reason for service. For the purpose of illustration only, aggregate outpatient service use categories and intensive services were examined.

Results

Application and reliability sample characteristics

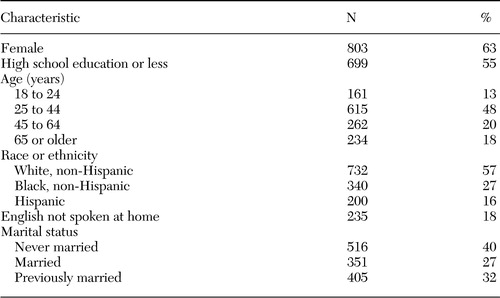

The sociodemographic characteristics of the complete sample of 1,279 participants are described in Table 1. Reliability analyses were carried out with 40 participants. No differences were found in service use or sociodemographic characteristics between the complete sample and the subsample.

Interrater reliability

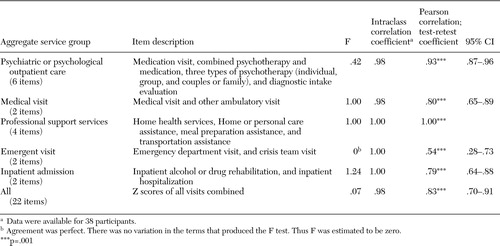

The intraclass correlation coefficients across all raters at the item level ranged from .52 to 1.00; 1.00 was the modal coefficient. No differential rater measurement bias was found for any of the items. Global indices were computed that aggregated individual items within each content area. Five indices were computed that corresponded to the aggregate service categories (outpatient psychiatric or psychological, outpatient medical, professional support, emergent visits, and hospitalizations). As shown in Table 2, the intraclass correlation coefficients at the scale level ranged from .97 to 1.00 across the three raters. No significant (.05 level) differential measurement bias was found in any of the scales.

Negative, positive, and overall agreement and kappa statistics were computed for every pair of raters. Negative agreement ranged from .89 to 1.00. Positive agreement ranged from .86 to 1.00. Overall agreement ranged from .87 to 1.00. Kappa statistics ranged from .86 to 1.00. Agreement for the categorical items ranged from 76.9 to 100 percent, with more than half of the items reflecting agreement over 90 percent (16 of 26 items, or 62 percent).

Test-retest reliability

Pearson correlations ranged from .47 to 1.00 at the item level and from .54 to 1.00 at the scale level (Table 2). The strength of the correlations both at the item and scale levels was moderate to high. Phi correlations between baseline and follow-up dichotomous variables (presence or absence of a service) ranged from .54 to 1.00, all of which were significant at the p<.001 level.

Application data

The CSI was used to describe the service use of a community sample. We examined the percentage of individuals who used a service, the average number of visits made, and, when meaningful, the reason for service. Because of space limitations, service provider characteristics are not detailed in this article.

Previous mental health visits. Less than one-third of the adults interviewed (401 patients, or 31 percent) made a mental health visit during the previous three months. Data from the CSI indicated that individuals who had sought treatment previously were seen in a variety of mental health settings. A total of 1,026 of the reported 4,096 mental health visits (25 percent) were to private practitioners, 1,067 (26 percent) were to outpatient mental health clinics, and 1,011 (25 percent) were to alcohol or drug facilities. The remaining 992 visits (24 percent) were to diverse social service agencies and other nonclassified facilities. The average duration of the visit was 34 minutes. No gender differences were found in previous service use, but significant differences were associated with race or ethnicity and age. White adults (273 patients, or 34 percent) used more services than black adults (72 patients, or 20 percent) or adults of Hispanic origin (55 patients, or 26 percent) (χ2=22.5, df=2, p<.01). Patients 65 years and older were less likely than those younger than 65 years to have used a mental health service (64 patients aged 65 years and older, or 23 percent, compared with 337 patients younger than 65 years, or 31 percent; χ2=5.09, df=1, p=.02).

Inpatient hospitalization. More than one-third of the sample (463 patients, or 36 percent) had one overnight stay in an inpatient facility during the past three months, with a total number of 8,928 hospital days. Of the days spent in the hospital, most (8,343 days, or 93 percent) were for mental health problems. The mean±SD length of stay for psychiatric hospitalizations was 20±25.7 days (range from 1 to 90 days). The mean duration of hospitalizations for physical reasons was 3±5.37 days (range from 1 to 60 days). There were no differences in age (65 years and older or 64 years or younger), gender, or race or ethnicity in having had a mental or physical health or inpatient admission in the past three months.

Emergency department visits. A total of 322 emergency department visits were made by 294 patients (23 percent). Close to one-third (101 visits, or 31.4 percent) of the emergency department visits were for a mental health problem. Among adults who made a visit to the emergency department, most reported only one visit. Adults younger than 65 years were more likely than those 65 years and older to have used the emergency department in the previous three months (255 patients, or 25 percent, compared with 33 patients, or 14 percent) (χ2=15.5, df=1, p<.001). White adults were less likely than Hispanic or black adults to use the emergency department (150 whites, or 20 percent, compared with 54 Hispanics, or 27 percent, and 90 blacks, or 26 percent) (χ2=9.34, df=2, p<.01). No gender differences were found. Only a small number of individuals (32 adults, or 3 percent) reported using crisis team services in the previous three months.

Previous medical visits. More than half of the individuals interviewed had made at least one medical visit (753 adults, or 59 percent), with a mean of 5.2±9.8 visits during the previous three months. Women were more likely than men to use this form of medical service (507 women, or 63 percent, compared with 246 men, or 51 percent) (χ2=13.01, df=1, p<.01). No differences were associated with race or ethnicity or age.

Discussion

The CSI was developed to address a need for a brief but detailed and reliable measure of mental health services used by adults. This article describes the development, administration, and reliability of the CSI and an application of the CSI in a community sample. The CSI reliably quantifies service use for non-cognitively impaired adults who received ambulatory services and provides information about the provider, site of service, reason for service, duration of service, and cost to the patient.

The CSI had good interrater and test-retest reliability in a mixed aged sample of adults who were seeking outpatient mental health treatment. Reliability coefficients were calculated for both individual service use items as well as service use aggregate categories. Study criteria excluded individuals with significant cognitive impairment, thereby improving test-retest reliability.

Preliminary findings of the CSI showed that white adults and adults younger than 65 years were more likely to have made a recent mental health visit before the index admission. White adults were more likely than black or Hispanic adults to use a service. These findings are consistent with the patterns of service use reported from epidemiologic studies. Differences in service use associated with race or ethnicity are consistent with analyses that found that racial differences persist even after controlling for education and income (12). Although income has been found to predict service use in the United States (13), total family income was not available to examine as a predictor of use or as a possible mediator of other predictors. Older adults used fewer outpatient mental health services than their younger counterparts (14).

In contrast to epidemiologic studies, this sample of adults was limited to persons who were seeking admission to mental health clinics. As such it is a self-selected population with a self-perceived need for services. Fifty-nine percent of our sample had made a medical visit, been hospitalized recently, or visited the emergency department, which suggests that many new admissions to the community clinics are referred from medical providers during a more intensive service, such as hospitalization or a emergency department visit. The comparable use of recent medical services among adults aged 65 years and older and those younger than 65 years may reflect a high rate of comorbid medical conditions, perhaps associated with chronic psychiatric illness, among adults who are younger than 65 years and seek mental health care.

A limitation of our study is the reliance of the CSI on respondent self-report. Although a trained interviewer conducted a careful interview and the period examined was reduced to three months, the accuracy of CSI information is dependent on the knowledge and recollection of the respondent. The limitation of self-report was evident in insurance coverage and out-of-pocket cost data. Data were collected at a time that managed care was introduced in Westchester County, and many respondents were not clear about their insurance type or coverage. Given this limitation, the insurance data reported cannot contribute to our understanding of the costs of services. In addition, further work is needed to establish validity by comparing self-report data with records available through administrative and clinical databases. However, it is noted that some self-report data—for example, day care and other services not reimbursed through claims—may not be available in administrative data sets.

Conclusions

The CSI offers a reliable snapshot of service use patterns across types, providers, and sites of service and of adults who seek mental health care. Capturing the services used by a given population offers an in-depth analysis of the impact of treatment use on the course of an illness and the costs of care. Since its development, the CSI has been used by a number of externally funded clinical research studies with different populations, including two multisite studies of depression in primary care—the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT) study (15,16) and the Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) intervention study (17,18).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant MH-53816 to Dr. Meyers and by grant MH-6681 to Dr. Sirey from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Sirey, Dr. Meyers, Dr. Bruce, and Dr. Raue are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, 21 Bloomingdale Road, White Plains, New York 10605 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Ramirez and Dr. Holmes are with the research division of the Hebrew Home for the Aged at Riverdale in Riverdale, New York. Dr. Teresi is with Columbia University Stroud Center and the department of psychiatry at New York State Psychiatric Institute in New York. Dr. Perlick is with the department of psychiatry at the Northeast Program Evaluation Center in West Haven, Connecticut.

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of 1,279 adults who were seeking care in outpatient mental health clinics and were given the Cornell Services Index

|

Table 2. Intraclass correlation coefficient for service use indices for three raters and test-retest coefficients between baseline and follow-up for 40 adults who were seeking care in outpatient mental health clinics and were given the Cornell Services Index

1. New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. DHHS pub SMA-03–3832. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003Google Scholar

2. Leaf PJ, Bruce ML: Gender differences in the use of mental health-related services: a reexamination. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 28:171–183,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. 1990 Client Sample Survey of Outpatient Programs. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MdGoogle Scholar

4. Holmes D, Teresi J, Holmes M, et al: Informal versus formal supports for impaired elderly: determinants of choice on Israeli kibbutzim. Gerontologist 29:195–202,1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Teresi J, Holmes D, Dichter E, et al: Prevalence of behavior disorder and disturbance to family and staff in a sample of adult day health care clients. Gerontologist 37:629–639,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Shea S, Starren J, Weinstock R, et al: Columbia University's Informatics and Telemedicine (IDEATel) Project: rationale and design. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 9:49–62,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Schneider L, Tariot P, Lyketsos CG, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials in Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE): Alzheimer's disease trial methodology. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 9:346–360,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Sirey J, Meyers BS, Bruce ML, et al: Predictors of antidepressant prescription and early use among depressed outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:690–696,1999Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Meyers BS, Sirey J, Bruce M, et al: Predictors of early recovery from major depression among persons admitted to community-based clinics: an observational study. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:729–735,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Databook 2001: Westchester County Department of Planning. County of Westchester, Department of Planning, 2001Google Scholar

11. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: "Mini-Mental State": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12:189–198,1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, et al: Administrative update: utilization of services. I. Comparing the use of public and private mental health services: the enduring barriers of race and age. Community Mental Health Journal 34:133–144,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Alegria M, Biji RV, Lin E, et al: Income differences in persons seeking outpatient treatment for mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:383–391,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Bartels SJ: Improving the United States' system of care for older adults with mental illness: findings and recommendations for the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11:486–497,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bruce ML, Pearson JL: Designing an intervention to prevent suicide: PROSPECT (Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly; Collaborative Trial). Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 1:100–112,1999Medline, Google Scholar

16. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, et al: Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients. JAMA 291:1081–1091,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al: Depression treatment in a sample of 1,801 depressed older adults in primary care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51:505–514,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Unutzer J, Katon W, Williams JW Jr, et al: Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Medical Care 39:785–799,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar