Need for and Use of Mental Health Services Among Parents of Children in the Head Start Program

Abstract

This study examined the prevalence of psychosocial difficulties and use of mental health services among 290 parents of children in the Head Start program. Data on demographic characteristics, child behavior problems, parents' difficulties, home environment, child behavior, and use of health services were collected. A total of 161 parents (56 percent) had identifiable psychosocial difficulties, and 41 (14 percent) reported use of mental health services in the previous 12 months. Child behavior problems, unmet need for mental and physical health services, and less optimal home environments were associated with parents' psychosocial difficulties. Parents who had an unmet need for mental health services were more likely to report behavior problems among their children.

A large body of research indicates that parents' mental health is an important factor in the health and well-being of their children (1). Furthermore, promoting the mental health of parents can be an important component of interventions to improve children's well-being (2). Because of the multiple stresses associated with both poverty and the parenting of young children, parents of children in the Head Start program may be at significant risk of mental health problems (3).

Head Start is a program of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that serves the child development needs of children from birth to the age of five years and their low-income families. With its explicit aim of supporting parental involvement and attending to the broad spectrum of physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development, Head Start may provide a useful context for assessing parents' mental health needs and facilitating access to treatment. The study reported here was intended to evaluate the prevalence of psychosocial difficulties in a population of parents of children in the Head Start program, demographic and family variables associated with parents' difficulties, and the extent to which parents with significant psychosocial difficulties use mental health services. A better understanding of these issues can inform the development of interventions to improve access to mental health services for families with low incomes.

Methods

Data were collected from one site of the Starting Early Starting Smart (SESS) study, a multisite trial that assessed the effectiveness of a preventive behavioral health intervention for families with young children. The intervention was conducted during the 1998-1999 school year and the 1999-2000 school year. Because these data are site specific, the findings of the study reported here are of limited generalizability to other sites.

The study participants were parents of four-year-old children who attended selected Head Start classrooms in Montgomery County, Maryland, a large suburb of the greater Washington, D.C., area. Classrooms were selected on the grounds that they had similar demographic patterns and staff willing to participate in an intervention trial. A total of 353 families were invited to participate, 290 (82 percent) of whom took part in the baseline assessment reported here. This high response rate suggests that differences between participants and nonparticipants—and the impact of these differences on outcomes—were negligible. Data were collected by trained research assistants during home-based interviews conducted in English or Spanish.

The parents and teachers completed the Preschool Kindergarten Behavior Scale (PKBS), a norm-referenced, standardized behavior-rating instrument (4). Children were considered to have behavior problems if they had a rating within the "moderate deficit" or "severe deficit" ranges on the internalizing or externalizing problem behavior scales. Alpha reliability coefficients were .91 for parent-completed scales and .96 for teacher-completed scales.

One primary objective of this investigation was to identify parents who were potentially in need of mental health services. Parents were considered to have psychosocial difficulties if they had a score within the clinical range on at least one of five measures: the Brief Symptom Inventory (5) (BSI), the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) (6), the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) (7), the Home Observation Measurement of the Environment (HOME) (8), and the Services Access and Utilization Scale (SAUS) (unpublished instrument developed by the SESS steering committee for use in this study).

The BSI is a well-validated instrument that asks respondents to rate how distressed they were during the previous seven days by using a list of psychological symptoms. In accordance with published guidelines, participants with T scores ≥63 on two of the subscales were considered to be in "distress" (5). Alpha reliability coefficients for the six BSI subscales ranged from .69 to .80.

The PSI-SF measures stress in the parent-child system as perceived by the parent. For this study, only the parent-child dysfunctional interaction subscale (PCDI) was evaluated. Parents with a subscale score at or above the 90th percentile were considered to be experiencing clinically significant levels of stress in the parent-child relationship (6). Alpha reliability for the PCDI was .88 for this sample.

The CTS is a well-validated self-report instrument that assesses aggression in the family. In accordance with established criteria, significant violence was defined by reports of at least three incidents of any violent act or one incident of "severe violence" (7). Alpha reliability for the CTS violence scale was .79. These measures of distress have been standardized in ethnically and economically diverse samples that correspond with national demographic distributions.

The HOME is an interview-observation measure that assesses the safety and stimulation of the child's home. The alpha reliability coefficient for the full scale was .82. Families with a score at or below the lowest quartile of the national SESS sample were considered to be in the at-risk range.

The SAUS is a semi-structured interview that assesses the use of community-based services by parents and children and was developed for the national SESS study. Parents were considered to have received mental health services during the previous year if they met with a professional for problems with "emotions" or "stress," participated in a support group to help with emotions or stress, attended a substance abuse treatment program, were admitted to a psychiatric facility for mental health or substance use problems, or received counseling or support services for domestic violence. The SAUS was also used to document the use of physical health services and assessed unmet need for behavioral health services as perceived by the respondent.

The unadjusted relationship of each predictor to parents' psychosocial difficulties was initially verified with point-biserial correlation analyses. Variables that were significant at p<.05 were included in multivariate logistic regression equations to identify those that were most strongly and independently associated with parents' psychosocial difficulties. Frequencies were tabulated, and chi square analyses were conducted to examine mental health service use among parents with psychosocial difficulties. These analyses were appropriate for the baseline analysis of a single site. Multisite, baseline, and longitudinal analyses of the SESS data will allow for greater use of dependent variables, such as individual BSI scales, because they will have greater power to detect statistical differences between groups.

Results

Forty-three percent of the families who participated in the study (125 families) were immigrants from Latin America, 22 percent (64 families) were immigrants from non-Latino (African, Caribbean, and Asian) countries, and 35 percent (101 families) were not immigrants. The mean±SD age of the children was 52±4 months (range, 38 to 60 months). A total of 151 children (52 percent) lived with both parents, 127 (44 percent) lived with a single mother, and 12 (4 percent) lived with other caretakers. The mean household income was $1,491 a month, and 62 percent of the primary caregivers (N=180) were employed. Sixty-eight percent of the parents (197 parents) had completed the 12th grade.

A total of 161 parents (56 percent) met the criteria for psychosocial difficulties. Of these, 107 (66 percent) were within the clinical range on the BSI alone, the CTS alone, or the PSI alone. Eighteen percent of the entire sample (54 parents) scored within the clinical range on two or three of these measures. A total of 124 parents in this sample (43 percent) met criteria for a psychosocial difficulty in that they had a score in the clinical range on the BSI alone. BSI subscales for the entire sample indicated clinical elevations on paranoid ideation (133 parents, or 46 percent), interpersonal sensitivity (110 parents, or 38 percent), obsessive-compulsive disorder (81 parents, or 28 percent), depression (78 parents, or 27 percent), anxiety (61 parents, or 21 percent), and hostility (61 parents, or 21 percent). For a number of parents, clinical elevations were also evident on the P-CDI (46 parents, or 16 percent) and the CTS (52 parents, or 18 percent).

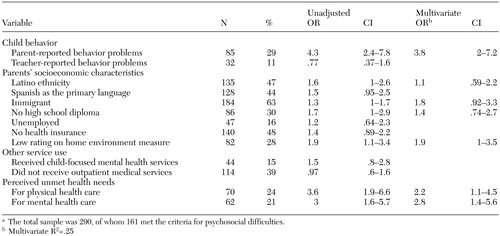

Parents' psychosocial difficulties were more frequently related to being an immigrant, being Latino, and not having completed high school (Table 1). Moreover, parent-reported child behavior problems, low ratings on the home environment measure, and perceived unmet need for physical and mental health services were also positively related to parents' psychosocial difficulties.

Eighty-four children (29 percent) met the criteria for behavioral problems as rated by their parents. Forty-one parents (14 percent) reported using mental health services in the previous 12 months. Despite the high prevalence of psychosocial difficulties in this group, only one-fifth of the parents with these difficulties (33 parents, or 21 percent) reported use of mental health services. Most commonly, parents who received mental health services reported that they had met individually with a health care professional—for example, a counselor, a therapist, or a physician—for problems with "emotions" or "stress" (24 parents, or 73 percent). However, 78 (63 percent) of the parents with elevated scores on the BSI, 37 (71 percent) of those with elevated scores on the CTS, and 34 (71 percent) of those with elevated scores on the P-CDI reported they did not use any mental health services. Thirty-nine parents with elevated CTS scores (89 percent) did not use domestic violence services, and almost none (three, or 2 percent) of the 161 parents who reported psychosocial difficulties used outpatient substance abuse treatment services. No parents reported use of inpatient substance abuse treatment services.

To help us understand service use patterns, the parents were asked about their perceptions of service need. Thirty-eight parents (31 percent) who had elevated BSI scores, 19 (43 percent) who had elevated CTS scores, and 12 (26 percent) who had elevated PCD-I scores reported that they "needed but did not receive" mental health services. Ninety-seven of the parents with psychosocial difficulties (76 percent) did not report either receipt of or perceived need for mental health services.

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, parent-reported child behavior problems, low ratings on the home environment measure, and unmet needs for physical and mental health services were each independent significant predictors of parents' psychosocial difficulties.

Child behavior problems were more frequently reported by parents who also reported a perception of unmet mental health service needs (χ2=11.5, df=1, p<.01) and unmet physical health service needs (χ2=6.4, df=1, p<.05). A trend was seen in the relationship between parents' ratings of child behavior problems and actual receipt of mental health services (p=.06) but not physical health services (p=.66).

Discussion

The results of this preliminary study suggest that psychosocial difficulties are common among parents of children in the Head Start program, with a frequency of 56 percent. Furthermore, most of these parents (80 percent) did not receive mental health services to address these difficulties. Our findings also suggest that many Head Start parents who have an unmet need for either mental or physical health services are likely to have children with significant behavioral problems.

Because of the large number of immigrants in this sample, this study provides information about an important but understudied group in the Head Start program. However, the results should be interpreted with caution, because the standardized measures we used were not validated in immigrant samples. For example, our finding that almost half of our study sample had scores in the clinically elevated range on the paranoid ideation subscale of the BSI may require further investigation. Endorsement of these items may reflect immigrants' experiences of suspicion and hostility rather than actual paranoid symptoms as measured by the BSI. In either case, these subjective experiences may deter parents from seeking health services and are therefore worth considering.

Conclusions

This study provided information about the extent of parents' psychosocial difficulties and the need for mental health services among parents of children in the Head Start program. In particular, the findings suggest that there is a need for outreach and dissemination of information about mental health services for parents. Because many Head Start programs are school based, health care professionals may collaborate with school personnel or have school-based services to encourage more contact and treatment of Head Start parents and families. This conclusion is especially important to consider in light of the significant financial and human resource challenges continually faced by Head Start programs as they attempt to address the myriad needs of families with low incomes. Increasing demands for an academic focus in the Head Start program may detract from opportunities to promote parental and family well-being and therefore should be considered carefully.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 5-U1H-SPO7983 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and its three centers as well as by Casey Family Programs. The study was supported by a research grant to Dr. Joseph. The authors thank Cheng Shao, M.D., Carolin Frey, Ph.D., Juanita Wiley, Melissa Rocklen, Wendy Albright, Mara Kailin, Maia Coleman, Katherine Marshall, and Carla Jenkins.

The authors are affiliated with the Center for Health Services and Clinical Research, Children's National Medical Center, 111 Michigan Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20010-2970 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics associated with psychosocial difficulties among parents of children in the Head Start program in unadjusted and multivariate analysesa

a The total sample was 290, of whom 161 met the criteria for psychosocial difficulties.

1. Downey G, Coyne JC: Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychological Bulletin 108:50–76, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mahoney G, Boyce G, Fewell R, et al: The relationship of parent-child interaction to the effectiveness of early intervention services for at-risk children and children with disabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 18(1):83–94, 1998Google Scholar

3. Billings A, Moos R: Comparisons of children of depressed and nondepressed parents: a social-environmental perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 11:463–486, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Merrell KW: Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scales, Test Manual. Brandon, Vt, Clinical Psychological Publishing, 1994Google Scholar

5. Derogatis LR: BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, Minn, National Computer Systems, 1993Google Scholar

6. Abidin RR: Parenting Stress Index, 3rd ed. Los Angeles, Western Psychological Services, 1995Google Scholar

7. Straus MA: Conflict Tactics Manual for the Conflict Tactics Scale Including Revised Versions CTS2 and CTSPC. Durham, NH, University of New Hampshire, 1998Google Scholar

8. Caldwell BM, Bradley RH: Administration Manual, rev ed: Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. Little Rock, Ark, University of Arkansas, 1984Google Scholar