Treatment Costs for Youths Receiving Multisystemic Therapy or Hospitalization After a Psychiatric Crisis

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors conducted a cost analysis for multisystemic therapy, an evidence-based treatment that is used as an intensive community-based alternative to the hospitalization of youths presenting with psychiatric emergencies. METHODS: Data from a randomized clinical trial that compared multisystemic therapy with usual inpatient services followed by community aftercare were used to compare Medicaid costs and clinical outcomes during a four-month period postreferral and a 12-month follow-up period. Data were from 115 families receiving Medicaid (out of 156 families in the clinical trial). RESULTS: During the four months postreferral, multisystemic therapy was associated with an average net savings per youth treated of $1,617 compared with usual services. Costs during the 12-month follow-up period were similar between treatments. Multisystemic therapy demonstrated better short-term cost-effectiveness for each of the clinical outcomes (externalizing behavior, internalizing behavior, and global severity of symptoms) than did usual inpatient care and community aftercare. The two treatments demonstrated equivalent long-term cost-effectiveness. CONCLUSIONS: Among youths presenting with psychiatric emergencies, multisystemic therapy was associated with better outcomes at a lower cost during the initial postreferral period and with equivalent costs and outcomes during the 12-month follow-up period.

Despite continued calls to include cost outcome analyses in evaluations of mental health practices, only a few adult treatment models (for example, behavioral substance abuse therapy [1] and Programs for Assertive Community Treatment [2,3,4,5,6,7]) and child treatment programs (for example, the Fort Bragg Demonstration Project [8] and Cannabis Youth Treatment [9]) have been subjected to economic evaluations. As noted by Lombard and colleagues (10), clinical researchers historically have developed interventions with the primary goal of maximizing clinical effects, and practitioners usually make treatment decisions on the basis of perceived therapeutic effectiveness. Yet economic constraints often are a determining factor in "real world" mental health service decisions (10,11).

The purpose of the study reported here was to provide a cost analysis of an evidence-based practice used as an intensive community-based alternative to the hospitalization of youths presenting with psychiatric emergencies. Cost-effectiveness analyses of alternative treatment services are especially necessary in light of the high cost of psychiatric hospitalization. However, no such evaluations have been conducted. In most communities, treatment for youths experiencing a psychiatric crisis consists of inpatient stays followed by aftercare services provided in the community. But inpatient care exhausts a disproportionate amount of available mental health dollars—studies show that hospital stays for children and adolescents average ten to 11 days nationally, at a cost of $700 to $1,000 per day (12,13,14,15).

In addition to the high cost of inpatient care, reviewers and policy makers have questioned the effectiveness of such services for children and adolescents (16). Although uncontrolled evaluations have demonstrated symptom reduction after the psychiatric hospitalization of youths (17), few controlled trials have been conducted. Until the study reported here was conducted, available evidence for the clinical effectiveness of psychiatric hospitalization came from small studies conducted in the 1970s and 1980s (18,19,20), and these studies showed inpatient care to be no more effective than alternative care in the community.

More recently, multisystemic therapy (21), a home-based treatment with established effectiveness for treating serious antisocial behavior among adolescents (22,23,24,25), was adapted for use among youths with serious emotional disturbance (26). In a randomized clinical trial of multisystemic therapy compared with usual inpatient services followed by community aftercare for youths presenting with psychiatric crises—suicidality, homicidality, or psychosis—youths who received multisystemic therapy evidenced greater short-term reductions in symptoms and dangerousness to self or others (27,28).

In addition, over the first four months postreferral, multisystemic therapy was associated with 75 percent fewer days hospitalized and 50 percent fewer days in other out-of-home placements compared with hospitalization with aftercare (29). Although multisystemic therapy was initially more effective than usual services at decreasing symptoms and out-of-home placements, these differences generally had dissipated by 12 to 16 months postreferral (30). Thus multisystemic therapy demonstrated greater short-term clinical effectiveness compared with usual services, but youths in both conditions had similar clinical outcomes in the long term.

This article examines the clinical outcomes associated with Medicaid costs during the four months postreferral, as well as cost-effectiveness during the 12-month follow-up period for this project. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first cost-effectiveness analysis conducted on alternative treatments of youths presenting with psychiatric emergencies. Multisystemic therapy was hypothesized to be more cost-effective than usual inpatient services followed by community aftercare.

Methods

Participants

Of the 177 families that were screened and that met criteria for the randomized clinical trial, 160 (90 percent) consented to participate in the study. Families who consented to participate did not differ from those who refused in terms of the adolescent's age, gender, or race. Of the 160 consenting families, three dropped out of the study before the first assessment. One youth who had been assigned to the hospitalization condition died in an automobile accident shortly before the posttreatment assessment. No additional families dropped out of the research portion of the study during the 12 months after treatment, leaving a final sample of 156, for a retention rate of 98 percent. Of these 156 families, 115 (74 percent) were receiving Medicaid and could be included in the analyses reported here. Recruitment began in 1995, and the clinical portion of the trial ended in 1999.

As discussed in a separate report of short-term outcomes of participants (27), all youths met the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry's (31) level-of-care placement criteria for psychiatric illness, as determined by an independent physician employed by the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Additional inclusion criteria were that the youths had to be aged between ten and 17 years, had to be Medicaid-funded or have no health insurance, and had to have a noninstitutional residential environment—the family home, the home of a relative, or a foster home (five youths were living in foster homes). Youths were not excluded because of preexisting physical, intellectual, or mental health difficulties, with the exception of autism. Informed consent was obtained from the custodial parents, and assent was obtained from the youths. All procedures were approved by MUSC's institutional review board.

Procedures

Youths were randomly assigned to treatment conditions (multisystemic therapy or hospitalization followed by usual aftercare services), and pairs (one youth receiving multisystemic therapy and one receiving usual services) were yoked in terms of the timing of assessments. After caregivers' consent and youths' assent had been provided, the family was informed of their treatment assignment by the opening of a sealed envelope. Research staff administered assessment batteries to family members either in their home or, for hospitalized youths, in the hospital, and families were paid $50 for each completed assessment to compensate for their time.

Assessments were conducted at five time points: within 24 hours of consent (time 1); shortly after the comparison youth was released from the hospital, with the yoked multisystemic therapy case assessed at the same time (time 2); at the completion of multisystemic therapy home-based services (multisystemic therapy lasted an average of four months postrecruitment), with the yoked comparison case assessed at the same time (time 3); six months after time 3 (time 4); and 12 months after time 3 (time 5).

The analyses reported here focused on clinical outcomes for the youths and Medicaid expenditures. Youths' symptoms were measured from youths' and caregivers' reports on two well-validated instruments. The Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory (GSI-BSI) (32) was completed by the adolescent as a measure of emotional distress. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (33) was completed by the adolescent's caregiver as a measure of the adolescent's internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Medicaid costs were assessed for all inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy, and other services. All costs were extracted from South Carolina Medicaid billing records and were taken from paid claims. Because each study participant was enrolled in Medicaid, the total direct treatment costs for the group receiving usual services are reflected in the Medicaid billing data. However, only specific portions of the costs for multisystemic therapy treatment were billed to Medicaid; the remainder of multisystemic therapy treatment costs was covered by the research grant. Following an "administrative perspective" (34), the total direct cost of these services—for example, salary, fringe benefits, local travel for therapists, and administrative assistance—was extracted from the grant budgets. For the multisystemic therapy group, this additional cost of therapy was added to the estimated Medicaid costs for the final evaluation of the treatment period (time 1 to time 3). This process reflects the assumption that such services would be paid for by Medicaid, if the multisystemic therapy treatment was certified as a billable, or standard, mode of therapy. Indeed, multisystemic therapy has recently been given a Medicaid code (H2033).

It should be noted that treatment costs for multisystemic therapy were included only in the analyses for time 1 through time 3, because multisystemic therapy did not include follow-up care—that is, any posttreatment care was provided by community providers and thus was included in the Medicaid costs for the youths in the multisystemic therapy condition. It also should be noted that multisystemic therapy costs were included as an average, per person. Although service use by family certainly differed—that is, multisystemic therapy is not a standard manualized approach that ends after a prescribed number of sessions but, rather, ends after treatment goals have been met—data were not available to separate costs by family.

Interventions

The two treatment conditions have been described in detail by Henggeler and colleagues (27) and by Huey and colleagues (28). A brief summary of implementation is provided here.

Multisystemic therapy. Multisystemic therapy is a community-based treatment that uses an intensive, home-based model of service delivery. Multisystemic therapy for youths with serious emotional disturbance and their families is specified in a recent clinical volume (26) that presents several important adaptations to the traditional multisystemic therapy approach in treating serious antisocial behavior (21).

In this clinical trial, multisystemic therapy was provided primarily by master's-level clinicians with caseloads of three families each. Medical coverage and crisis support were provided by residents in child and adolescent psychiatry and crisis caseworkers, respectively. The lead clinical supervisor was a child and adolescent psychiatrist, who was supported by a doctoral-level psychologist. Clinical supervision followed a specified protocol (35) and was the primary method for ensuring treatment fidelity. In addition, a multisystemic therapy expert coded audiotapes of family treatment sessions for each therapist weekly, and adherence measures (36) were collected from families monthly to provide immediate feedback to the clinician and the supervisor.

Usual services. All youths who had been randomly assigned to the comparison condition were admitted to the MUSC Youth Division Inpatient Psychiatric Unit for stabilization of their psychiatric crisis. Physicians and nursing and social work staff provided services and developed an aftercare plan for each youth and his or her family. As noted by Henggeler and colleagues (27), the high quality of the inpatient program was supported by objective and independent indexes. Moreover, aftercare services were relatively strong, given that Charleston was one of the original system-of-care sites funded by the federal government.

Data analyses

A programmatic perspective was used in comparing the cost-effectiveness of multisystemic therapy with that of usual services. That is, the impact of multisystemic therapy compared with usual services was evaluated on Medicaid spending only. The Medicaid costs were compared for all inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy, and other services during two periods. First, costs for each youth who received multisystemic therapy were extracted from the time the youth entered the study until the defined end of active multisystemic therapy (time 1 through time 3). Each youth who received multisystemic therapy was matched to a youth receiving usual services, based on time of entry into the study, so the Medicaid costs of the youth receiving usual services were measured over the same time frame as his or her matched multisystemic therapy youth.

Similarly, Medicaid program treatment costs for the 12-month follow-up period (time 3 though time 5) were extracted for each youth who received multisystemic therapy and his or her matched usual services youth. Costs during the initial period (time 1 through time 3) were highly skewed for both groups—Medicaid spending for several individuals was four or five times the average. Consequently, the top five spending outliers were excluded from each group—youths with costs in excess of $29,000 during the treatment period for the multisystemic therapy group and in excess of $39,000 for the usual services group. To check the sensitivity of the results to this exclusion, the models were reanalyzed with the entire sample. The results were qualitatively identical.

Once the appropriate periods for each study participant were defined, the raw Medicaid spending across the multisystemic therapy and usual services groups was compared for the time 1 through time 3 period and for the time 3 through time 5 period by using simple t tests. However, given that expenditures and outcomes can vary for many reasons unrelated to initial treatment decisions—for example, race and severity of symptoms—regression-based (least squares) cost and outcome models, or "risk-adjusted" models (37,38,39,40), were also estimated. The outcome (dependent) variables were the total Medicaid paid claims or the measured score on the clinical outcome scales (for the relevant periods).

Independent predictors were an intercept, an indicator variable for whether the youth was receiving multisystemic therapy or usual services, and available risk factors. These factors included the youth's age and race, the caregiver's age and educational level, the number of caretakers in the household, and a variable representing the interaction between the treatment duration and the treatment condition. To control for individual differences in symptom level in the Medicaid cost models, youths' baseline GSI scores at time 1 and at time 3 were also included as covariates; the GSI score at time 1 was included in the treatment period model (time 1 to time 3), and the GSI score at time 3 was included in the follow-up period model (time 3 to time 5). For the clinical outcome models (GSI, externalizing behaviors, and internalizing behaviors), the value of the corresponding clinical scale at time 1 for the treatment period model and at time 3 for the follow-up period model were included as covariates to control for any initial differences in clinical scores.

Results

The average age of the 115 youths who were included in the analyses was 12.6±2.12 years. Seventy-seven (67 percent) were male, 85 (74 percent) were African American, and 28 (24 percent) were white. Twenty-seven youths (23 percent) lived in two-parent households, and 60 (52 percent) lived in single-parent households. This demographic breakdown was the same as that for the full sample of 156. As expected, the subsample of 115 families receiving Medicaid was slightly less advantaged than the overall sample of 156: a total of 97 families (84 percent) were receiving welfare, compared with 109 families (70 percent) in the overall sample, and the median monthly family income from employment was $300, compared with $592. Other participant characteristics (for example, diagnoses) and treatment outcomes (for example, symptom changes, behavioral changes, and placement outcomes) for the clinical trial sample are described in detail elsewhere (27,29,30).

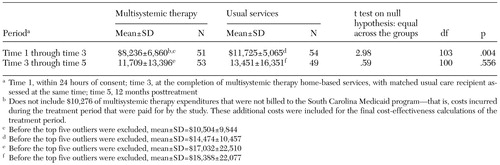

The average Medicaid costs for the youths who received multisystemic therapy and those who received usual services in each period are presented in Table 1. Comparisons of the raw means for direct Medicaid expenditures rejected the hypothesis that costs were the same in both groups during the treatment period (time 1 through time 3)—Medicaid spending was higher in the usual services group. Comparison of the means rejected the hypothesis of equal spending during the follow-up period (time 3 through time 5)—Medicaid spending was statistically equivalent across groups. Note that these figures reflect the raw Medicaid spending and do not include the additional costs for multisystemic therapy that were paid directly from grant funds. These costs are included in the final cost-effectiveness ratios for the treatment period. In addition, the risk-adjusted regression-based models, described below, included factors that may have contributed to differences in programmatic spending besides initial treatment choices.

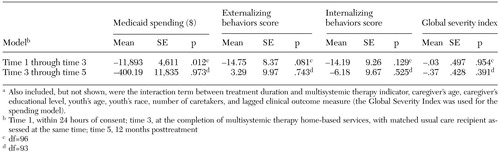

The risk-adjusted cost (Medicaid) and outcome (GSI, externalizing behaviors, and internalizing behaviors) models for the two periods are presented in Table 2. GSI scores can range from 0 to 4, and CBCL T scores can range from 50 to 100. These estimates indicate that multisystemic therapy saved the South Carolina Medicaid program, on average, $11,893 per youth during the initial postreferral period (p=.01). When the additional non-Medicaid treatment costs paid from grant funds ($10,276 per youth) were considered, the average programmatic savings was reduced to $1,617 per youth during the treatment period. This finding suggests that multisystemic therapy would save Medicaid money if it were certified as a treatment option. However, the impact of multisystemic therapy on Medicaid spending in the 12-month follow-up period was less advantageous, at a savings of $400 per youth, which was not statistically significant. Thus youths had about the same level of spending after time 3 irrespective of whether they had been randomly assigned to multisystemic therapy or to usual services.

The results for the clinical outcome scales for time 1 through time 3 also are presented in Table 2. In addition to being associated with a moderate cost savings ($1,617 per youth), multisystemic therapy was associated with marginally significant short-term improvements in externalizing behaviors of about one and one-half a standard deviation (15 points; p=.08). As with the Medicaid spending model, multisystemic therapy demonstrated no statistically significant effect on externalizing behavior in the long run compared with standard care. Although the impact of multisystemic therapy on internalizing behavior during the treatment period (14 points) suggests a clinical improvement, the effect was not statistically significant, and the GSI scores evidenced little between-group differences. Consequently, the evidence suggests that multisystemic therapy does no better—and no worse—than standard care in these dimensions.

By using these estimates, the cost-effectiveness of multisystemic therapy and usual services were calculated. Sample means were used to calculate average costs and outcomes for the sample. Costs were adjusted by the estimated net impact ($1,617) for the multisystemic therapy group. Similarly, outcomes for the clinical scores for the time 1 through time 3 period were adjusted for the multisystemic therapy group by the estimated treatment effect. The ratios were calculated by using the following equation:

where i=externalizing behaviors, internalizing behaviors, or GSI scores and j=period (time 1 through time 3 or time 3 through time 5).

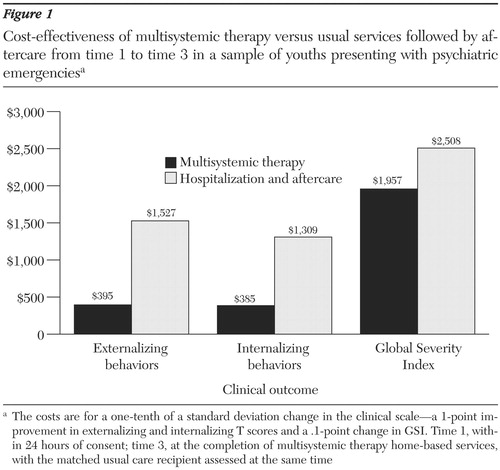

To make the ratios clinically meaningful, they were adjusted so that the dollar figure derived from this equation would indicate the average cost per one-tenth of a standard deviation change in the clinical scale—that is, a one-point change in CBCL externalizing and internalizing behavior T scores and a .1-point change in GSI. As can be seen from Figure 1, multisystemic therapy is a more economically efficient mode of therapy immediately after an acute episode. For example, a 1-point improvement in externalizing behaviors was associated with a cost of $395 for youths receiving multisystemic therapy, whereas the same improvement was associated with a cost of $1,527 for those receiving usual services. Given that no differences were observed in Medicaid costs or in clinical outcomes during the 12-month follow-up period, multisystemic therapy and standard therapy have comparable cost-effectiveness after time 3. Therefore, because multisystemic therapy is associated with marginally better or similar outcomes at a lower cost during the initial postreferral period and with equivalent costs and outcomes in the 12-month follow-up period, multisystemic therapy seems to be the economically preferred treatment option.

Discussion

By using data from a randomized clinical trial that compared multisystemic therapy with usual inpatient services followed by community aftercare, we compared Medicaid costs and clinical outcomes during a period of approximately four months postreferral and during the 12-month follow-up period. After adjustment for costs paid by the research grant, multisystemic therapy was associated with an average net savings of $1,617 per youth treated during the initial postreferral period. Costs during the 12-month follow-up period were equivalent between treatments.

Although direct cost savings of multisystemic therapy per youth compared with usual services was somewhat moderate, a critical question is to compare the cost-effectiveness of the two treatments. To analyze cost-effectiveness, the cost comparisons were related to risk-adjusted clinical outcomes—that is, self-reported psychiatric symptoms and caregiver-reported internalizing and externalizing behaviors—for youths in each treatment condition. Combined with the cost savings generated, multisystemic therapy demonstrated better short-term cost-effectiveness for each of the clinical outcomes than did usual inpatient care followed by community aftercare. Because neither costs nor clinical outcomes differed during the 12-month follow-up period, the two treatments demonstrated equivalent long-term cost-effectiveness.

Although modest, these findings are consistent with the recent report of broader clinical outcomes from this trial (30), showing that youths who were treated with multisystemic therapy initially had better outcomes than youths who received usual services but that these differences were not maintained long-term. (A discussion can be found in reference 30). When used among antisocial youths, multisystemic therapy has previously demonstrated substantial short- and long-term clinical outcomes across several randomized trials (41). However, the clinical experience and research findings from this initial trial of multisystemic therapy with a challenging psychiatric sample led to considerable reconceptualization of the nature and organization of multisystemic therapy services when provided for youths with serious emotional disturbance and their families. For example, the chronicity and complexity of the problems experienced by the youths and their family members have necessitated that multisystemic therapy services be even more intensive and include considerable psychiatric support, that short-term access to out-of-home care—for example, respite care and kinship care—be provided, and that therapeutic support beyond the typical four-month duration of multisystemic therapy be made available.

Such adaptations to the standard multisystemic therapy treatment protocol clearly made services for treating youths in psychiatric crisis more expensive than is typically the case in providing multisystemic therapy to serious juvenile offenders. Although the cost of multisystemic therapy to treat offenders averages approximately $5,500 per family (42), costs for treating youths in this psychiatric sample exceeded $10,000 per family. Interestingly, the costs to Medicaid during the 12-month follow-up period were nearly identical for the youths who received multisystemic therapy and those who received usual services: just over half the costs were from office-based services (54 percent and 57 percent, respectively), and just under half were from hospital-based services (42 percent and 41 percent, respectively).

This study had limitations in terms of the generalizability of the findings to other populations and treatments. The sample consisted solely of youths who were enrolled in Medicaid. Thus the findings cannot be generalized to a more economically advantaged population. In addition, multisystemic therapy is a well-specified treatment with intensive quality assurance, so the findings cannot be generalized to other home-based treatment models.

Conclusions

In summary, although multisystemic therapy proved to be more cost-effective than usual inpatient care followed by community aftercare in this sample of youths presenting with psychiatric emergencies, the adaptation of multisystemic therapy for treating a psychiatric population is still undergoing revision and study. The need for replication of these findings is clear.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by grant R01-MH-51852 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Henggeler, Dr. Rowland, and Dr. Schoenwald are stockholders in MST Services Inc., which has the exclusive licensing agreement through the Medical University of South Carolina for the dissemination of multisystemic therapy technology and intellectual property.

Dr. Sheidow, Dr. Henggeler, Dr. Rowland, Dr. Halliday-Boykins, and Dr. Schoenwald are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and Dr. Bradford and Dr. Ward with the department of health administration and policy at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Send correspondence to Dr. Sheidow at the Family Services Research Center, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, MUSC, 67 President Street, Suite CPP, Box 250861, Charleston, South Carolina 29425 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Cost-effectiveness of multisystemic therapy versus usual services followed by aftercare from time 1 to time 3 in a sample of youths presenting with psychiatric emergenciesa

a The costs are for a one-tenth of a standard deviation change in the clinical scale—a 1-point improvement in externalizing and internalizing T scores and a .1-point change in GSI. Time 1, within 24 hours of consent; time 3, at the completion of multisystemic therapy home-based services, with the matched usual care recipient assessed at the same time

|

Table 1. Medicaid expenditures for youths presenting with psychiatric emergencies who received multisystemic therapy or usual services followed by aftercare

|

Table 2. Risk-adjusted cost and outcome model estimates for time 1 through time 3 and for time 3 through time 5, excluding outliers, for a sample of 115 youths presenting with psychiatric emergencies who received either multisystemic therapy or usual services followed by aftercarea

a Also included, but not shown, were the interaction term between treatment duration and multisystemic therapy indicator, caregiver's age, caregiver's educational level, youth's age, youth's race, number of caretakers, and lagged clinical outcome measure (the Global Severity Index was used for the spending model).

1. Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Birchler GR: Behavioral couples therapy for male substance-abusing patients: a cost outcomes analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:789–802, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Latimer EA: Economic impacts of assertive community treatment: a review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 44:443–454, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wolff N, Helminiak TW, Diamond RJ: Estimated societal costs of assertive community mental health care. Psychiatric Services 46:898–906, 1995Link, Google Scholar

4. Essock SM, Frisman LK, Kontos NJ: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment teams. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:179–190, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lehman AF, Dixon L, Hoch JS, et al: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:346–352, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Rosenheck RA, Neale MS: Cost-effectiveness of intensive psychiatric community care for high users of inpatient services. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:459–466, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Clark RE, Teague GB, Ricketts SK, et al: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment versus standard case management for persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Health Services Research 33:1285–1308, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bickman L: A continuum of care: more is not always better. American Psychologist 51:689–701, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. French MT, Roebuck MC, Dennis ML, et al: The economic cost of outpatient marijuana treatment for adolescents: findings from a multi-site field experiment. Addiction 1:84–97, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Lombard DN, Haddock CK, Talcott GW, et al: Cost-effectiveness analysis: a primer for psychologists. Applied and Preventive Psychology 7:101–108, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Eddy DM: Clinical decision making: from theory to practice: cost-effectiveness analysis: is it up to the task? JAMA 267:3342–3348, 1992Google Scholar

12. Burns BJ: Mental health service use by adolescents in the 1970s and 1980s. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 30:144–150, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Chabra A, Chavez GF, Harris ES, et al: Hospitalization for mental illness in adolescents: risk groups and impact on the health care system. Journal of Adolescent Health 24:349–356, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Martin A, Leslie D: Psychiatric inpatient, outpatient, and medication utilization and costs among privately insured youths, 1997–2000. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:757–764, 2003Link, Google Scholar

15. Pottick K, Hansell S, Gutterman E, et al: Factors associated with inpatient and outpatient treatment for children and adolescents with serious mental illness. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:425–433, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Sondheimer DL, Schoenwald SK, Rowland MD: Alternatives to the hospitalization of youth with a serious emotional disturbance. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 23:7–12, 1994Google Scholar

17. Pfeiffer SI, Strzelecki SC: Inpatient psychiatric treatment of children and adolescents: a review of outcome studies. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 29:847–853, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Flomenhaft K: Outcome of treatment for adolescents. Adolescence 9:57–66, 1974Medline, Google Scholar

19. Langsley DG, Pittman FS, Machotka P, et al: Family crisis therapy: results and implications. Family Process 7:145–158, 1968Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Winsberg BG, Bialer I, Kupietz S, et al: Home vs hospital care of children with behavior disorders: a controlled investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:413–418, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, et al: Multisystemic Treatment of Antisocial Behavior in Children and Adolescents. New York, Guilford, 1998Google Scholar

22. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

23. Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

24. National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment: Blueprint for Change: Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 2001Google Scholar

25. Kazdin AE, Weisz JR: Identifying and developing empirically supported child and adolescent treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:19–36, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Rowland MD, et al: Serious Emotional Disturbance in Children and Adolescents: Multisystemic Therapy. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

27. Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, Randall J, et al: Home-based multisystemic therapy as an alternative to the hospitalization of youths in psychiatric crisis: clinical outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1331–1339, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Huey SJ Jr, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, et al: Multisystemic therapy effects on attempted suicide by youth presenting psychiatric emergencies. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43:183–190, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Schoenwald SK, Ward DM, Henggeler SW, et al: Multisystemic therapy versus hospitalization for crisis stabilization of youth: placement outcomes 4 months postreferral. Mental Health Services Research 2:3–12, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins C, et al: One-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy as an alternative to the hospitalization of youths in psychiatric crisis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42:543–551, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Level of Care Placement Criteria for Psychiatric Illness. Washington, DC, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1996Google Scholar

32. Derogatis LR: Brief Symptom Inventory (BS): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, Minn, National Computer Systems, 1993Google Scholar

33. Achenbach TM: Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington, Vt, University of Vermont, department of psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

34. Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, et al: Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

35. Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK: The MST Supervisory Manual: Promoting Quality Assurance at the Clinical Level. Charleston, SC, MST Services, 1998Google Scholar

36. Henggeler SW, Borduin CM: Multisystemic Therapy Adherence Scales. Charleston, SC, Medical University of South Carolina, department of psychiatry and behavioral science, 1992Google Scholar

37. Hendryx MS, Moore R, Leeper T, et al: An examination of methods for risk-adjustment of rehospitalization rates. Mental Health Services Research 3:15–24, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Fries BE, Morris JN, Aliaga P, et al: Risk adjusting outcome measures for post-acute care. American Journal of Medical Quality 18:66–72, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Weissman EM, Rosenheck RA, Essock SM: Impact of modifying risk adjustment models on rankings of access to care in the VA mental health report card. Psychiatric Services 53:1153–1158, 2002Link, Google Scholar

40. Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, et al: Risk-adjusted mortality rates as a potential outcome indicator for outpatient quality assessments. Medical Care 40:237–245, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Sheidow AJ, Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK: Multisystemic therapy, in Handbook of Family Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice. Edited by Sexton TL, Weeks G, Robbins M. New York, Brunner-Routledge, 2003Google Scholar

42. Aos S, Phipps P, Barnoski R, et al: The Comparative Costs and Benefits of Programs to Reduce Crime. Olympia, Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 2001Google Scholar