Rehab Rounds: Supplementing Supported Employment With Workplace Skills Training

Abstract

Introduction by the column editors: Supported employment, as designed for persons with serious and persistent mental illness, has been termed individual placement and support. In two randomized controlled trials (1,2), clients who received individual placement and support services were more likely to obtain at least one job in the competitive sector, to work more hours, and to have a higher total income than their counterparts who received more traditional types of vocational rehabilitation. However, individual placement and support did not improve the length of time the employed participants kept their jobs.An adjunctive or additional element of individual placement and support, aimed at improving the job tenure of individuals with mental illness, would be a constructive contribution to the vocational rehabilitation for this population. In a previous Rehab Rounds column, Wallace and colleagues (3) described the development of the workplace fundamental skills module, a highly structured and user-friendly curriculum designed to teach workers with mental illness the social and workplace skills needed to keep their jobs. The workplace fundamental skills module supplements individual placement and support by conveying specific skills that enable workers to learn the requirements of their jobs, anticipate the stressors associated with their jobs, and cope with stressors by using a problem-solving process. The earlier report described the production and validation of the module's content. The purpose of this month's column is to present the preliminary results of a randomized comparison of the module's effects on job retention, symptoms, and community functioning when coupled with individual placement and support. To enable wide generalization of the findings of the study, the program was conducted in a typical community mental health center.

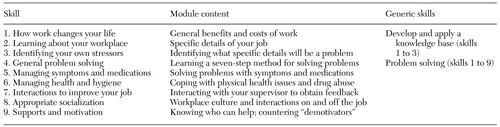

Like all the skills training modules produced in the social and independent living skills series of the University of California, Los Angeles (4), the workplace fundamental skills module is a self-contained curriculum that teaches participants the skills of a major domain of functioning, in this case the workplace skills depicted in Table 1. It should be emphasized that the module is not focused on helping participants find a job. It does not teach skills such as obtaining job leads, producing a résumé, and participating in a job interview. These skills are covered in supported employment or other job-finding services; the workplace fundamental skills module complements these services but does not supplant them.

Operation of the module

As with all the modules, each skill in the workplace fundamental skills module is taught with use of seven "learning activities," administered in the following sequence: introduction, videotaped demonstration, role-play practice, generation and evaluation of solutions to resource management problems, generation and evaluation of solutions to outcome problems, completion of in vivo assignments, and completion of homework assignments. The sequence has participants acquire and practice the behaviors, overcome the obstacles that could prevent them from performing the skill, and then practice the skill outside the training environment.

To ensure that the training is faithfully conducted across settings, staff, and participants, each module is produced and distributed with three highly structured components: a videotape, a trainer's manual, and a participant's workbook. The videotape provides clear, graphic, and annotated peer modeling of the behaviors to be acquired. The trainer's manual specifies the lesson plans that are used to implement and evaluate each session. The workbook—"Job Organizing Book," or JOB—consists of work sheets and checklists that involve participants in an active learning process that highlights the "fit" between the person's characteristics and the job's demands. This process enables the clinician and the participant to engage in problem solving by learning requisite skills for meeting the expectations of the job or making needed accommodations to improve the individual's functioning and satisfaction at work. The completed JOB constitutes an individualized action plan that can be reviewed and revised by the participant and his or her support staff at any time.

Because the workplace fundamental skills module is focused on the skills needed to keep a job, it is particularly relevant for people who are engaged in a job search or those who have just been hired. However, if a participant is ambivalent about obtaining a job, participation in the module may serve as a preview of the requirements, expectations, and rewards that might be encountered in a workplace. Thus a positive learning experience with the module can desensitize individuals who have apprehension or concerns about the consequences of working, thereby promoting readiness for rehabilitation. Even if a participant has been employed for some time, and there is no evidence of pending difficulties or termination, participation in the module can reinforce and illuminate the skills currently being used in the workplace.

Evaluation

An evaluation of the workplace fundamental skills module was conducted in collaboration with the Santa Barbara County Department of Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Health Services. The aim was to determine whether the module helped workers keep their jobs by comparing the outcomes achieved by workers who were exposed to both individual placement and support and the workplace fundamental skills module with those of workers who engaged in individual placement and support services only.

The selection of participants began by the project staff's meeting with the county's case management teams and asking them to review their rosters of clients to identify eligible participants. Those who were eligible had a diagnosis of a schizophrenia-spectrum or mood disorder on the basis of DSM-IV criteria, were considered occupationally disabled, had a disabling disorder of at least two years' duration, did not have a primary diagnosis of substance abuse, had no inpatient treatment during the previous three months, were aged 18 to 70 years, expressed an interest in obtaining competitive employment within six weeks of enrollment in the study, and had at least two unsuccessful job experiences with terminations in the previous three years. The eligibility criteria were crafted to recruit persons whose background characteristics and problematic work histories suggested that they might benefit from the workplace fundamental skills module.

Once prospective participants were identified, a project staff member joined the next regularly scheduled meeting of the individual with his or her case manager to explain the project in detail and to answer any questions asked by the potential participant. If the person agreed to participate, he or she signed an informed consent form, and an appointment was scheduled for administration of the baseline assessments.

Forty-two individuals participated in the study, 50 percent of whom were men. Fifty-four percent had schizophrenia, 43 percent had bipolar disorder, and 3 percent had another psychotic disorder. Sixty-two percent had never been married, 1 percent were married, and 28 percent were divorced. The participants' average education level was 13.9 years. The participants were randomly assigned to receive either individual placement and support only or individual placement and support plus the workplace fundamental skills module. An employment specialist who worked half-time and whose task was to conduct assessments and match participants with appropriate jobs staffed each group.

For the clients who received individual placement and support only, two part-time job supporters provided ongoing supportive contacts, helped them overcome job-related obstacles, and, when desirable, consulted with their employers and workplace supervisors. For clients who received both modalities, the same two job supporters provided similar supports and problem solving but also assisted participants in using the skills they learned during training sessions. Both the employment specialist and the job supporters exchanged clinical information and progress reports weekly with each participant's multidisciplinary team, regardless of the client's treatment condition.

The two-hour fundamental skills sessions were conducted on a twice-weekly schedule by either of the two job supporters. The duration of training was three months, and individual make-up sessions were provided as needed. Only five participants dropped out of the study, for a variety of reasons—for example, moving out of the area or being arrested and jailed. However, no significant differences were observed between the two treatment conditions in the number of participants who dropped out nor on any of the pretest measures or demographic factors. The fidelity of both conditions was assured by checklists based on optimal delivery of each intervention (5,6).

A total of 34 participants—17 in each group—were employed during the duration of the project. No significant differences were found between the groups' total earnings ($4,239 in the group receiving individual placement and support only and $3,002 in the group receiving both individual placement and support and the workplace fundamental skills module) or hours worked (597 in the individual placement and support group and 427 in the group receiving both modalities). However, the individual placement and support group held significantly more jobs than the other group (1.9 compared with 1.2), indicating that there was significantly more job turnover in the group that received individual placement and support only. Furthermore, the members in this group were significantly less satisfied with their jobs than those in the group receiving both modalities (4.4 compared with 5.4, scored on a 7-point scale on which 7 represents the highest level of satisfaction). For the measures of psychopathology and social functioning, no significant differences between the groups were observed on any measure.

Afterword by the column editors: The most noteworthy finding from this preliminary comparison between two types of vocational rehabilitation was the greater job retention among the participants who received the combination of individual placement and support and the workplace fundamental skills module. The greater tenure in a job for the combined treatment condition provided support for the initial hypothesis about the module's additive value in improving job retention among clients receiving individual placement and support. The ability to hold on to a job may have been gained because of the specialized and focused training that participants in the combined condition received in identifying and coping with stressors on the job.

One might consider the possibility that increased job turnover is actually favorable in enabling clients to try different jobs until they find one that is a better match and provides greater satisfaction. However, the fact that the clients who received both modalities reported significantly greater job satisfaction belies this explanation. Taking the findings as a whole, the supplementary skills training in workplace fundamentals may be a useful adjunct to supported employment given that job turnover can be demoralizing for mental health clients and an obstacle to their mastery of job opportunities and the establishment of new social relationships.

The generalizability of these findings to other mental health programs was enhanced through implementation of the study in a typical mental health center staffed by a standard mix of nonacademic, multidisciplinary professionals and paraprofessionals. Both the workplace fundamental skills module and individual placement and support are manual-based treatments that facilitate dissemination of the procedures to a diverse array of practitioners working in most psychiatric facilities. The methods of both services can be adopted by neophyte paraprofessionals who have limited experience working with persons with severe mental illness as well as by more experienced clinicians who can put their own professionally informed stamp on the techniques.

A more complete report of this project will be published in the future, including the research design, quantitative results, and statistical analysis. In addition, two randomized controlled trials of individual placement and support in conjunction with the workplace fundamental skills module are under way at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the New Hampshire -Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center among individuals with recent-onset schizophrenia as well as those with more chronic forms of schizophrenia.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grant MH-57029 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Wallace.

Dr. Wallace is adjunct professor of medical psychology and Mr. Tauber is research associate in the department of psychiatry of the University of California, Los Angeles, Neuropsychiatric Institute. Send correspondence to Dr. Wallace at Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consultants, Box 2867, Camarillo, California 93012 (e-mail, [email protected]). Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., and Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Skill areas of the workplace fundamentals module for persons with serious mental illness

1. Drake RE, McHugo GJK, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391–399, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lehman AF, Goldberg R, Dixon LB, et al: Improving employment outcomes for persons with severe mental illnesses. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:165–172, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wallace CJ, Tauber R, Wilde J: Keep your job: teaching fundamental workplace skills to mentally ill workers. Psychiatric Services 50:1148–1153, 1999Link, Google Scholar

4. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: the UCLA social and independent living skills modules. Innovations and Research 2:43–60, 1993Google Scholar

5. Drake RE, Fox TS, Leather PK, et al: Regional variation in competitive employment for persons with severe mental illness. Administrative Policy in Mental Health 34:71–82, 1998Google Scholar

6. Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, MacKain SJ, et al: Effectiveness and replicability of modules for teaching social and instrumental skills to the severely mentally ill. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:654–658, 1992Link, Google Scholar