Preliminary Outcomes From an Integrated Mental Health Primary Care Team

Abstract

The effects of establishing a multidisciplinary mental health primary care team in a Veterans Affairs internal medicine primary care clinic were evaluated. The multidisciplinary team worked in collaboration with primary care providers to evaluate and treat their patients, who had a wide variety of psychiatric disorders, in the primary care clinic. In the first year of operation preliminary outcomes indicated that the rate of referrals to specialty mental health care dropped from 38 percent to 14 percent. The mean number of appointments with the team for evaluation and stabilization was 2.5. These outcomes suggest that a multidisciplinary mental health primary care team can rapidly evaluate and stabilize patients with a wide range of psychiatric disorders, reduce the number of referrals to specialty mental health care, and improve collaborative care.

Psychiatric conditions are prevalent in the primary care setting (1,2). Concerns about the provision of adequate care for the patients with these conditions include underdiagnosis of psychiatric disorders, long waiting times for mental health consultations, poor communication between primary care and mental health providers, and suboptimal care for primary care patients with psychiatric disorders (3,4,5).

A mental health primary care team was developed at a Veterans Affairs internal medicine primary care clinic to address these concerns. The term "collaborative care" has been used to describe how mental health providers work with a group of providers to treat common psychiatric disorders in the community or in primary care clinics (6,7,8,9,10). Using the collaborative care approach, we created a multidisciplinary team to provide clinical support to primary care providers. The team was designed to enable rapid evaluation and stabilization of patients with a wide range of psychiatric disorders, to improve the ability of the primary care providers to deliver ongoing management of these disorders, to improve the education of clinical staff and trainees on topics related to primary care psychiatry, and to reduce the number of referrals to specialty mental health care.

In this report we describe the organization of the multidisciplinary mental health primary care team and report preliminary evidence of its effectiveness.

Methods

The general internal medicine clinic is the primary care clinic for the Seattle Division of the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System. Before the mental health primary care team was created, mental health services at the clinic were provided by a psychologist, a psychology intern, and part-time psychiatry residents who functioned as independent practitioners working in parallel with primary care providers. In addition, patients could be referred to a mental health clinic located in another building. Concerns about this system included long waiting lists for mental health services, poor coordination of mental health and primary care services, lack of integration with social work and chaplain services, and lack of structured mental illness education for patients or staff.

The multidisciplinary mental health team was created at the start of fiscal year (FY) 2000. Its members were drawn from existing mental health staff from the clinic: the psychologist, a psychology intern, psychiatry residents, clinical social workers, and a chaplain. An attending psychiatrist contributes the equivalent of one day of team and resident supervision each week and provides limited clinical services. Because this was a study of a new clinical program and not a research project, approval from a human subjects committee was not required.

To address the concerns listed above, all primary care patients referred for mental health care are evaluated by the team with the goal of rapidly treating and stabilizing them. Patients who are referred to the team are scheduled and seen at the primary care clinic. The team communicates evaluation and treatment recommendations to the primary care provider verbally and through the electronic medical record. Patients are referred for specialist mental health care only if their symptoms are sufficiently severe or chronic to prevent quick stabilization or management within the context on the primary care clinic or if their medication regimens are deemed too complicated for a typical primary care provider. For example, a patient with bipolar disorder who is taking several mood stabilizers and an antipsychotic would be referred.

The coordinated approach includes a diagnostic evaluation using a biopsychosocial-spiritual method. Treatment options include individual or group psychotherapy, medication management, social worker support, and chaplain services. Whenever possible, the mental health team returns stabilized patients to the primary care provider for further care and does not provide long-term treatment. This approach allows the team to be available for new referrals and improves collaboration between team members and primary care providers. The mental health team meets weekly to discuss and create treatment plans for complicated cases.

Team members, including psychiatrists and psychologists, respond to formal referrals by seeing these patients in regularly scheduled clinics within the general internal medicine clinic. Team members also provide informal mental health information to aid primary care providers ("curbside" or by telephone or e-mail). By being on-site, the team's psychiatrists and psychologists are available to respond to urgent requests from the primary care provider and to see these patients that day, or they can sit in with the primary care provider to address urgent concerns about patients. The mental health team routinely provides didactic training to primary care staff. The team also trains psychiatry residents, psychology interns, and social work interns on aspects related to primary care psychiatry. Team members educate patients through psychoeducational classes.

As an objective measure of the team's effectiveness, we compared the number of referrals to specialty mental health care services in the year before the team's inception (FY 1999) and in the first year of its operation (FY 2000). Workload data for the psychiatry and psychology team members during the first year were evaluated as another objective outcome measure of program success. Data on referrals and workload are kept by each clinic and were used in the study.

Results

During FY 2000 the general internal medicine clinic had 9,656 enrolled patients, compared with 8,829 in FY 1999, representing an increase of approximately 9 percent. The patients' average age was 53 years; more than 90 percent were male. Primary care providers included 17 internal medicine physicians, 22 nurse practitioners, ten internal medicine fellows, and a variable number of internal medicine residents.

In FY 1999, before implementation of the mental health primary care team, 543 consultations occurred with the mental health providers in the clinic. Of these 543 patients, 205 (38 percent) were subsequently referred to specialty mental health care. In FY 2000, the mental health team received 560 consultations, but only 81 (14 percent) were referred for specialty mental health services, which represents a significant change (uncorrected χ2=77.85, df=1, p<.001). We evaluated how this change compared with the overall pattern of mental health referrals between FY 1999 and FY 2000. In FY 1999, mental health services received 820 consultations, and this number increased to 1,157 in FY 2000. Thus there was a dramatic decrease in the number of clinic referrals to specialty mental health services at a time of marked increase in referrals from other sources.

Specific diagnostic data for patients who were referred to the mental health team are not available, but the most common diagnoses included affective and anxiety disorders; schizophrenia, somatoform disorders, dementia, and grief reactions were not uncommon. The most common reasons for referral from the multidisciplinary team to specialty mental health services included depression (40 percent of patients), anxiety disorders other than posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (13 percent), bipolar disorder (10 percent), PTSD (10 percent), need for anger management services (8 percent), addictions (5 percent), schizophrenia (5 percent), and need for other therapy (18 percent). Typically these patients had refractory illness or chronic suicidal ideation or needed specialized groups and support services that are available only through specialty mental health care clinics.

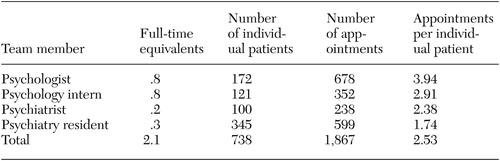

Workload data for the mental health team members during the first year of the team's operation are shown in Table 1. Patients were stabilized and returned for follow-up to their primary care providers after an average of 2.5 appointments.

Discussion and conclusions

The multidisciplinary mental health primary care team is a coordinated team intended to decrease fragmentation of care between mental health and primary care, improve collaboration between providers, and integrate specialist mental health care into the primary care setting. Our data suggest that the team can quickly evaluate and stabilize patients with psychiatric disorders and reduce the number of referrals to specialty mental health services. These are retrospective, preliminary measures, which function as indicators of effectiveness. Prospective studies of longer duration will be needed to establish the team's effectiveness.

Although minimal, the added attending psychiatrist's time may have contributed to the reduction in referrals. It is also possible that these results would have been different with a more predominately female population. We received considerable unsolicited praise from staff and patients. Staff appreciated the easy access to specialty care, advice on treatment options, and the ability to remain the patient's primary provider. Patients appreciated being able to stay with their primary provider and being able to receive care in the primary care setting instead of having to go to the mental health clinic.

We report data only from the first year of operation. However, the team continues to function with the same staff and remains fully integrated into the primary care clinic. Our impression is that the success of the team requires ongoing attention to improving relationships between primary care and mental health providers. Specific issues to address include communication, patients' expectations of care, understanding of roles, and need for rapid supervision in dealing with semiurgent problems (4,6). Success also appears to be related to sustaining close clinical collaboration with the primary care provider, which can help minimize the number of mental health follow-up appointments and, as a result, keep the team's providers available for rapid consultation about patients. Results from this study provide the groundwork for future detailed prospective studies of effectiveness.

Dr. Felker, Dr. Barnes, Dr. Greenberg, Dr. Chaney, and Dr. Shores are affiliated with the mental health division of the Department of Veterans Affairs in Seattle and with the department of psychiatry and behavioral medicine of the University of Washington in Seattle. Ms. Gillespie-Gateley and Ms. Buike are with the social work division and Ms. Morton is chaplain of the Department of Veterans Affairs in Seattle. Send correspondence to Dr. Felker at the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, MHC-116, 1660 South Columbian Way, Seattle, Washington 98108-1597 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Workloads of members of a multidisciplinary mental health primary care team over a one-year period

1. Katon W, Schluberg H: Epidemiology of depression in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry 14:237–247, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Barsky A, Delamater B, Orav J: Panic disorder patients and their medical care. Psychosomatics 40:50–56, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Meadows G: Establishing a collaborative service model for primary mental health care. Medical Journal of Australia 168:162–165, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kates N, Craven M, Crustolo A, et al: Integrating mental health services within primary care: a Canadian program. General Hospital Psychiatry 19:324–332, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Valenstein M, Klinkman M, Becker S, et al: Concurrent treatment of patients with depression in the community provider practices, attitudes, and barriers to collaboration. Journal of Family Practice 48:180–194, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

6. Mueser K, Bond G, Drake R, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37–74, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Felker B, Workman E, Stanley-Tilt C, et al: The psychiatric primary care team: a new program to provide medical care to the chronically mentally ill. Medicine and Psychiatry 1:36–41, 1998Google Scholar

8. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273:1026–1031, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:924–932, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, Felker B, et al: Effectiveness of collaborative care depression treatment in VA primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 18:9–16, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar