Economic Grand Rounds: Policy Implications of Adverse Selection in a Preferred-Provider Organization Carve-Out After Parity

Assessing potential cost effects of mental health parity in carve-out plans is difficult for behavioral health plans and policy makers, especially when they are relying on results from studies of individual plans. In particular, adverse selection can occur when a plan covers only part of an employer's population. When health care consumers have multiple health plans available to choose from, common sense and economic theory predict that consumers will maximize returns from their health benefits. If consumers with above average health care needs prefer one plan to others, risks and costs will not be distributed across health plans in proportion to enrolled members, resulting in adverse selection. Whether consumers actually select health care plans to maximize their benefits is an empirical question that has significant policy implications. If adverse selection occurs, its effects may confound conclusions about the effects of parity.

Frank and McGuire (1) identified two general classes of mental health plan carve-outs and explained how they differ in their potential for adverse selection. In a full mental health carve-out, all employees are covered by the same mental health plan, so there can be no adverse selection. However, in a partial carve-out, mental health benefits are carved out for only one of several competing health plans. Individual employees are covered by the mental health carve-out plan only if they choose that particular health plan. If the carved-out mental health benefits are perceived as being better than those offered by competing health plans, employees with greater than average needs for behavioral health services have an incentive to select the plan with carved-out behavioral health benefits.

Evidence shows that earlier experience with mental illness, either personally or in one's family, influences an employee's choice of health plan (2,3,4). In particular, plans that offer more flexibility or greater coverage are preferred—for example, a full coverage plan, which includes basic plus major medical, is preferred over a health maintenance organization (3) and an indemnity insurance plan is preferred over a managed care plan (4). These studies support the notion that adverse selection can and does occur in partial carve-outs. Of immediate concern is whether these preferences result in cost differences that are sufficient to distort conclusions about the cost impact of parity.

Parity legislation reduces the disparities between mental health and medical benefits within plans. However, when medical benefits differ between plans, mental health benefits also differ, which still allows for adverse selection to occur. Thus evaluating parity on the basis of results from a behavioral health carve-out from one of several competing health care plans may be misleading, because apparent cost increases may be confounded by adverse selection. Only in a full carve-out, in which adverse selection is not possible, can cost increases more clearly be attributed to increased benefits and demand for mental health care.

The purpose of our study was to compare plans of two major California employers who received behavioral health benefits from United Behavioral Health (UBH) and evaluate whether adverse selection occurred in behavioral health carve-out plans after limited parity was introduced. Parity legislation in California applied only to severe mental illness.

Methods

We used a pre-post design to evaluate the use and costs before and after parity among new users for both employers' plans. New users were defined as members who had not used UBH services in the previous 12 months.

One employer's plan, serving more than 23,000 members, is a full carve-out that serves all employees through a partially insured contract. In this full carve-out UBH primarily provides administrative services and also assumes responsibility for direct behavioral health costs beyond contractually specified levels. The other employer's plan, serving more than 58,000 members, is a partial carve-out for a preferred-provider organization (PPO) health plan. These members have the option of choosing the PPO with the partial carve-out or one of several health maintenance organizations, which do not offer as many provider choices or which control access to services more tightly. UBH assumes full risk under the partial carve-out contract, that is, it is a capitated contract in which UBH assumes responsibility for all direct behavioral health costs. When managing these different carve-out plans, UBH makes no distinctions on the basis of the degree of risk assumed under the contracts.

All employees of both employers reside in and receive services in California. The employers are in the same industry and their employees have similar levels of income and education. Both plans became subject to California's parity legislation in January 2001, the beginning of the full carve-out's third year with UBH and the partial carve-out's second year with UBH. Changes in mental health benefits that resulted from parity were communicated to employees of both plans during open enrollment in the fall of 2000. Employees who were with the employer that purchased the full carve-out could not change mental health plans. Employees who were with the employer that purchased the partial carve-out could change medical plans, and thus mental health plans, during this time, with changes effective in January 2001. At the time parity was introduced, the employer that offered the partial carve-out closed another medical plan, an indemnity plan. Data were not available for behavioral health services provided by other health plans of the partial carve-out employer.

Our analysis used a broad definition of costs that was inclusive of all services for which the managed behavioral health organization was responsible. Although the California parity legislation did not mandate benefits for substance abuse treatment, simply broadening mental health benefits may increase the diagnosis of mental health conditions relative to the diagnosis of substance use disorders as clinicians seek reimbursement for treatment of diagnoses with improved coverage under parity. For this reason, limiting our analysis of costs to those for mental health services is potentially misleading and risks misidentifying a shift in diagnosis patterns as an increase in mental health spending. As a result, we examined total behavioral health spending under each employer's benefit structure. Similarly, cost data also include amounts that employers and employees paid to eliminate any effects of cost transfers between the employer and employee as a result of parity. All cost figures represent specialty behavioral health services, such as psychotherapy, medication management, and inpatient hospitalization, but exclude pharmaceutical and nonspecialty services provided by primary care physicians. Finally, cost data represent all amounts paid for services provided by the time of the study in 2001.

Adverse selection could have occurred in two ways. First, benefit changes resulting from parity might make a plan more attractive to members with a greater need for services, providing an incentive for them to switch plans. Alternatively, the indemnity plan offered by the employer with the partial carve-out may have been subject to adverse selection before parity was introduced. The closure of the indemnity plan could have caused a shift of high-use members to the PPO carve-out. In either case, these new members would be expected to use behavioral health services at a higher rate and to be more costly than other new users. Therefore, new users were subdivided into previous members—individuals eligible before a specific quarter—and new members—individuals first eligible in a specific quarter. Two quarters were studied, the last quarter before parity (the fourth quarter of 2000) and the first quarter of parity (the first quarter of 2001). The ratio of the number of new users that were also new members to the total number of new users was computed to determine whether members who recently became eligible for UBH services entered care at a higher rate after parity. Also, to assess whether new members were more costly than previous members, costs for new and previous members were compared for the entire first year after parity. Adverse selection would be suggested by greater rates of use of new members, higher costs for new members, or both in the partial carve-out compared with rates and costs in the full carve-out plan following the introduction of parity.

Results

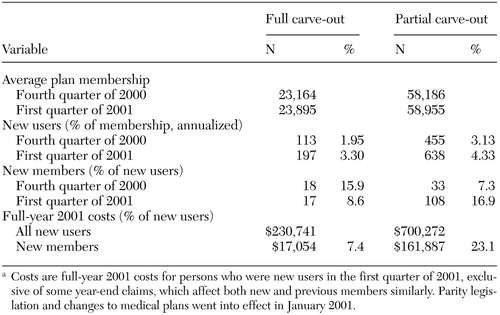

The rates of new users increased for both employers in the first quarter of 2001, as shown in Table 1, although this was a short-term effect. However, the composition of these new users differed sharply between employers. Under the full carve-out, the share of new users who were new members decreased, whereas under the partial carve-out, newly eligible members made up an increased share of new users, as shown in Table 1.

Full-year costs were compared for all services that were provided to persons who became new users in the first quarter of 2001. Under the full carve-out, the costs for new members were slightly lower than costs for previous members: $1,003 per year for a new member compared with $1,187 per year for a previous member. However, under the partial carve-out, costs for new members were substantially higher: $1,499 per year for a new member compared with $1,016 per year for a previous member. Table 1 shows the share of full-year costs for new members compared with all new users.

Discussion and conclusions

For both full and partial carve-outs a temporary increase in costs was seen among new users, possibly because of seasonal effects or parity. Under the full carve-out, new users came from an influx of previous members. Costs for new and previous members were proportionate to their numbers. However, under the partial carve-out, new members sought behavioral health care at much higher rates than they did before parity. Furthermore, under the partial carve-out, new members were much more costly on average than previous members. The difference in behavioral health care use between employers does not appear to be due to greater incentives to manage care for a contract with greater assumed risk; in fact, the opposite appears to be true. The partial carve-out employer was fully insured by UBH and use sharply increased. However, under the full carve-out contract UBH had little risk and use decreased.

The study data support the idea that adverse selection occurred with the partial carve-out, possibly because it was a carve-out for a PPO plan, the least restrictive option available to employees when parity began. However, questions remain because the source of the adverse selection is unclear. The partial carve-out employer's indemnity plan was likely subject to adverse selection historically. Its closure probably pushed many high-use patients to seek care in the other plans that were available. However, data were not available for members of the closed plan on their use history or on their distribution to the remaining plans, so we cannot be certain that that was a source of adverse selection. The study was also limited in that we did not test whether increased costs resulted from increased expenses for mental health or substance abuse service expenses or both. Our interest was in the direct and indirect effects of parity and adverse selection on all behavioral health costs, so mental health and substance abuse costs were combined, limiting our ability to study the cost components.

Specifically identifying the direct effects of parity legislation would require a more fine-grained analysis that would consider details of the legislation, such as which diagnoses were covered and for which populations, for example, adults or children. Finally, employees choosing the PPO health plan may have done so on the basis of overall health benefits rather than mental health benefits, and the observed results may simply be a residual outcome from those decisions. Although it is possible that employees chose the PPO because of overall health benefits, evidence from other studies has shown that health plan choice is influenced by a specific need for behavioral health services (2,3,4). In addition, costly medical conditions often are comorbid with costly mental health conditions, so it is possible that any adverse selection that occurred for medical reasons also influenced the use of behavioral health services. In the absence of medical data we could not test this hypothesis.

However, none of these limitations changes our conclusions. Partial carve-outs provide the opportunity for adverse selection, and there is evidence from this and other studies that adverse selection occurs. We assume that reasonable consumers will maximize their outcomes from health care benefits. Our data support that assumption and suggest that when consumer behavior results in adverse selection, such selection should not be misinterpreted as an effect of parity. It is clear that drawing conclusions about parity must be done cautiously when using data obtained from studies of partial carve-outs. Only under full carve-outs, in which adverse selection is not possible, can a clearer picture be obtained. Decision makers should thus be cautious in using parity cost studies from individual benefit plans that are not full carve-outs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the helpful comments received from William Goldman, M.D., and Roland Sturm, Ph.D.

Dr. Branstrom is a senior research analyst in the behavioral health sciences department at United Behavioral Health, 425 Market Street, 27th Floor, San Francisco, California 94105 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Cuffel is director of U.S. outcomes research at Pfizer in New York. At the time of this study Dr. Cuffel was vice president of the behavioral health sciences department at United Behavioral Health. Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Member and user data for two employers who received behavioral health benefitsfrom United Behavioral Health, by type of carve-outa

a Costs are full-year 2001 costs for persons who were new users in the first quarter of 2001, exclusive of some year-end claims, which affect both new and previous members similarly. Parity legislation and changes to medical plans went into effect in January 2001.

1. Frank RG, McGuire TG: The economics of behavioral health carve-outs. Managed Behavioral Health Care 78:41–47, 1998Google Scholar

2. Ellis RP: The effect of prior year health expenditures on health coverage plan choice, in Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research. Edited by Scheffler R, Rossiter L. Greenwich, Conn, JAI Press, 1985Google Scholar

3. Deb P, Rubin J, Wilcox-Gök V, et al: Choice of health insurance by families of the mentally ill. Health Economics 5:61–76, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Perneger TV, Allaz AF, Etter JF, et al: Mental health and choice between managed care and indemnity health insurance. American Journal of Psychiatry 52:1020–1025, 1995Google Scholar