Psychiatric Emergencies After the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Population surveys suggest that the events of September 11, 2001, resulted in psychiatric emergencies in U.S. communities. This study tested the extent of such emergencies in San Francisco. METHODS: Interrupted time-series designs were applied to counts of emergency calls to the police during the 424-day period beginning January 1, 2001, and of voluntary and coerced admissions to psychiatric emergency services during the 1,620-day period beginning July 1, 1997. RESULTS: The number of men and women who were coerced into treatment increased significantly on Thursday, September 13, but the number of voluntary admissions was as expected. The number of telephone calls from citizens that police dispatchers judged to be mental health related increased significantly on Wednesday, September 12, and remained elevated through September 13. Several additional analyses were conducted to test the stability of the findings, and the results were essentially unchanged. CONCLUSIONS: The events of September 11 may not have induced emergent mental illness in U.S. communities at relatively great distance from the attacks. However, it is possible that persons with severe mental illness were either more evident to or less tolerated by the community.

Despite the fact that the published literature (1,2,3,4,5,6) has left open the question of whether the events of September 11, 2001, were responsible for clinically significant psychiatric disorder in the affected communities or elsewhere, the Institute of Medicine has encouraged psychiatrists to plan for future terrorist attacks (7). We tried to inform such planning by reviewing the literature and testing related hypotheses by using data from San Francisco.

Assessments of the psychological sequelae of the terrorist attacks of September 11 have yielded mixed findings. There appears to be agreement that the residents of New York and other attack sites were significantly distressed by the events (1,2,5). A survey of Manhattan residents found that acute depression, panic attacks, and other symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder were elevated in the days after the attacks (2). Two other surveys discovered similar evidence of elevated disorder among the persons living nearest the attack sites (1,5). A study of two groups of workers described only as "highly involved in the events of September 11" by virtue of their "industries and geography" revealed a small but statistically significant increase in the workers' use of anxiolytics in October 2001 (6).

Less agreement has emerged on the question of whether the events of September 11 affected the incidence of psychological distress in communities other than the attack sites. One national survey of adults found that 44 percent of Americans reported coping with "substantial symptoms" of psychological distress in the days immediately after the attacks (1). The findings caused those who conducted the survey to infer that "this as an attack not just on the East Coast, but on the whole nation, and they reacted strongly to it (8)." However, another national survey found no such evidence, leading the authors to report that "overall distress levels in the country were within normal ranges" (5). These findings raise the question of whether the circumstances gauged by the surveys led more than expected numbers of persons to be treated for emergent psychiatric illness. Indeed, reports of such increases in the attacked communities abound in the popular media (9). Systematically addressing the question would either add to or detract from the argument that ambient stressors, of which the events of September 11 are an extreme example, induce sufficient pathology in the population to warrant rapid, if time limited, expansion of psychiatric services.

The scholarly literature includes correspondence (not refereed articles) from two different research teams that attempted to detect changes in service use among veterans and military personnel who were in or near communities that were attacked on September 11 (3,4). Neither of these studies showed a significant increase in the number of persons who sought help from service providers. The authors of one of the studies suggested that further assessment needs to be conducted of service use in populations other than current or former military personnel living in the attacked communities (3).

The literature on risk factors for psychiatric illness has produced conflicting hypotheses about the effect of September 11 on the incidence of treated psychiatric emergencies. The literature on stress suggests that the incidence of emergent illness will increase and, in turn, cause an increase in the number of persons seeking mental health services.

Not all persons who are treated for psychiatric emergencies seek treatment. Local health authorities coerce a considerable fraction into treatment for being a danger to themselves or others or for being gravely disabled (10). The events of September 11 may have increased the number coerced into treatment through two mechanisms. The fact that respondents to one survey alluded to above (1) reported "angry outbursts" suggests that more persons than otherwise expected may have met criteria for coerced treatment in the days immediately after the terrorist attacks.

The number of persons coerced into treatment could also have increased even if the number meeting the criteria for such treatment remained constant. The greatly expanded police presence on the streets immediately after the attacks could simply have led to a higher rate of discovery of such persons. The number of coerced admissions could also have increased despite the presence of a constant population of persons who met the criteria for coercion if the community's tolerance for deviance decreased after September 11. Lower tolerance for deviance would have led to more requests by citizens for the police to do something about disordered persons who had been observed previously but ignored.

Not all speculation on the effects of September 11 has involved a hypothesis of increased treatment of emergent psychiatric illness. For example, the social support literature suggests that the outpouring of social interaction reportedly induced by the attacks may have been sufficiently therapeutic to avert the use of formal services (3). Ninety-eight percent of the respondents in one of the national surveys (1) reported talking to someone about the feelings induced by the attacks. Ninety percent turned to religion for comfort. Sixty percent reported participating in group activities to "ease their anxieties." This heightened social contact may have not only kept the newly symptomatic out of the clinics but also reduced demand among persons with persistent mental illness who might otherwise have sought or been coerced into treatment.

We attempted to determine which of these possible explanations best fits data describing calls to the San Francisco police to deal with disordered persons and the incidence of treated psychiatric emergencies in the city and county of San Francisco. More specifically, we tested two hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that more persons than otherwise expected were admitted into emergency psychiatric treatment in San Francisco on September 11 and during the next six days. We tested the hypothesis separately for coerced and voluntary admissions of men and women. Second, we hypothesized that more calls than otherwise expected were made to the San Francisco police requesting help dealing with disordered persons on September 11 and during the next six days.

Methods

Data

The data for the study were provided by the San Francisco Department of Public Health and the San Francisco police department. Our first test was based on daily counts of all men and women aged 18 years or older who were admitted to the following categories of service: emergency room crisis stabilization, urgent care crisis stabilization, or crisis intervention. We eliminated duplicate counts due to transfers between facilities by identifying episodes in which the same client received services at different facilities within a 48-hour period. We then used legal status codes to separate the daily counts into coerced and voluntary admissions.

The admissions data included the 1,620 days beginning July 1, 1997, and ending December 6, 2001, representing the most recent data available at the time of the analyses. The mean±SD number of daily admissions was 4.85±2.36 for women who were coerced into treatment, 2.97±1.96 for women who were admitted on a voluntary basis, 8.4±3.09 for men who were coerced, and 4.73±2.57 for men who were admitted voluntarily. No data on age, race, or ethnicity were available to us for this test. All data were collected under protocols approved by the responsible institutional review boards and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant R01-MH-43579).

The second test used daily counts of telephone calls from the public to the San Francisco police department for which, on the basis of the caller's description of the situation, the police dispatcher judged that the call might involve a candidate for mental health treatment. These types of calls are given a radio code of either 800 (mentally disturbed person) or 5150 (mental health detention). All calls received by the police department are recorded in a data management system, records of which include the time and date of the call, the location of the situation about which the call was made, and the names of the officers who responded. Calls to which no unit responded were not included. The calls data included the 424 days beginning January 1, 2001, and ending February 28, 2002, representing the most recent data available at the time of the analyses.

Design

All correlational tests turn on whether the observed values of the dependent variable differ, as predicted by theory, from the values expected under the null hypothesis. These tests typically assume that the expected value under the null hypothesis is the mean of the observed values throughout the test period. However, time series often exhibit autocorrelation, including trends, cycles, and the tendency to remain elevated or depressed after high or low values (11). Autocorrelation complicates the testing of hypotheses, because the expected value of an autocorrelated series is not its mean. Epidemiologists often address this problem by expressing autocorrelation as an effect of earlier values of the dependent variable itself (11,12,13,14,15,16). Therefore time-series equations used in tests like ours often include earlier values, or "lags," of the dependent variable among the predictors. The residuals from a time-series equation with the correct lags exhibit no autocorrelation. The researcher can then add other independent variables to the equation to determine whether their coefficients are different from zero in the hypothesized direction.

Removing autocorrelation from the dependent variable before testing the effect of the independent variable has the added benefit of avoiding spurious associations induced by shared trends and cycles. The estimated coefficients are net of shared autocorrelation.

Analyses

Thus we began our tests by modeling autocorrelation in the daily count of men and women who were voluntarily or involuntarily admitted to emergency services, or in the number of calls to the police department about disordered persons. These tests and all statistical analyses were performed by the first author.

We used the strategy attributed to Dickey and Fuller (17) as well as that of Box and Jenkins (18) to identify and model autocorrelation. The strategy—autoregressive, integrated, moving average (ARIMA) modeling—draws from a very large family of models that express autocorrelation in time series.

We then added a binary variable that was scored 1 for September 11, 2001, and 0 otherwise. We specified the variable with no delay as well as with delays of one through six days to test changes in admissions for September 11 and the next six days. The estimated coefficients for the September 11 variable were net of autocorrelation.

Results

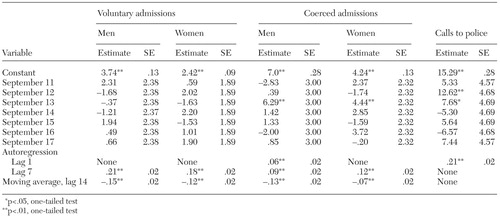

The estimated coefficients for the admissions data for September 11 through 17 are shown in Table 1. The Dickey-Fuller test showed that all four admission series were stationary in their mean. The ARIMA parameters suggested that all four series exhibited autocorrelation such that daily admissions were predicted by those of one and two weeks earlier, although with decreasing power. Coerced admissions of men also exhibited autocorrelation such that unusually high or low values were followed a day later by elevated or depressed values of decreasing absolute size.

As can be seen from Table 1, the number of men and women who were coerced into treatment increased significantly on Thursday, September 13. The fact that we rejected the null hypothesis only for persons who were coerced into treatment suggests that imminently violent or gravely disabled persons were either more frequently detected or less tolerated, or both.

As can also be seen from the table, the number of citizen calls that were judged by police dispatchers to be mental health related increased significantly on Wednesday, September 12, and remained elevated through September 13. This finding suggests that reduced community tolerance for deviance accounted, at least in part, for the increase in coerced treatment.

We conducted several additional analyses to test the stability of our findings. We deleted the statistically nonsignificant parameters from the equations and estimated the remaining coefficients; all remained significant. We added "all Wednesdays" (all Wednesdays scored 1, other days scored 0) and "all Thursdays" (all Thursdays scored 1, other days scored 0) binary variables to the test equations for calls and admissions to determine whether these days of the week simply exhibited higher rates of calls and admissions, producing type I errors for September 12 and 13. The September 12 and 13 coefficients for the numbers of both men and women who were coerced into treatment and for the number of calls to the police remained significant.

We conducted an additional analysis to determine the sensitivity of the results to our specification of autocorrelation. We used "next best" ARIMA models for the dependent variables and estimated the equations again. The results were essentially unchanged.

Discussion and conclusions

Data from San Francisco do not support the speculation that the events of September 11, 2001, were responsible for emergent, clinically significant mental illness in American communities that were geographically distant from the sites of the attacks. It appears, rather, that both the increased presence of public and private security personnel and reduced community tolerance for deviance led to an increase in coerced treatment of persons with severe mental illness.

Our data describe emergencies that were treated in a public mental health system. Therefore our results may not generalize to persons who receive services primarily in the private sector. Moreover, even if data from all providers in San Francisco were available, we would not know whether the results applied to other communities at similar distances from the sites of the attacks, which, of course, is true of the findings already reported in the literature.

Replicating our analyses elsewhere would provide the definitive estimate of the external validity of our findings. Additional tests of our finding on coerced treatment would also allow the estimation of any "dose response" associated with distance from the point of attack. Although geographic distance would be the most intuitive "x-axis" for such response models, social distance could be considered in further tests. For example, we could rank communities on the per capita number of telephone calls to or from the attack sites on the day of the attacks. This approach would allow testing of the intuitive hypothesis that communities that are more socially tied to those attacked would exhibit more voluntary and involuntary treatment.

Our findings imply that the events of September 11 affected persons with mental illness in San Francisco, and perhaps elsewhere, in ways not shared by the population at large. The community apparently lost tolerance, at least temporarily, for such persons. Although this circumstance may not have implications for the organization or staffing of mental health services in times of crisis, it may tell us more about the social circumstances that induce or amplify the stigma of mental illness.

Professor Catalano and Mr. Kessell are affiliated with the department of public health biology and epidemiology at the School of Public Health, 320 Warren Hall, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. McConnell and Ms. Pirkle are with the community behavioral health services section of the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

|

Table 1. Parameter estimates for tests of the association of the events of September 11, 2001, with psychiatric emergencies and psychiatrically related calls to the police in San Francisco (N=1,620 days)

1. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox L, et al: A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. New England Journal of Medicine 345:1507–1512, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 346:982–987, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rosenheck R, Schuster M, Stein B, et al: Reactions to the events of September 11. New England Journal of Medicine 346:629–630, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hoge C, Pavlin J: Psychological sequelae of September 11. New England Journal of Medicine 347:443, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, et al: Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: findings from the national study of Americans' reactions to September 11. JAMA 288:581–588, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. McCarter L, Goldman W: Use of psychotropics in two employee groups directly affected by the events of September 11. Psychiatric Services 53:1366–1368, 2002Link, Google Scholar

7. Institute of Medicine: Preparing for the Psychological Consequences of Terrorism: A Public Health Strategy. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2003Google Scholar

8. Hellmich N: September 11 stress unsettled our sleep, upset the kids. USA Today, Nov 15, 2001, p D10Google Scholar

9. Goode E, Eakin E: Mental health: the profession tests its limits. New York Times, Sept 11, 2002, p A1Google Scholar

10. Monahan J, Hoge SK, Lidz C, et al: Coercion and commitment: understanding involuntary mental hospital admission. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 18:249–263, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Catalano R, Serxner S: Time series designs of potential interest to epidemiologists. American Journal of Epidemiology 126:724–731, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Catalano R, Frank J: Detecting the effect of medical care on mortality. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 54:830–836, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Catalano R: Economic antecedents of mortality among the very old. Epidemiology 13:133–137, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Catalano R, Libby A, Snowden L, et al: The effect of capitated financing on mental health services for children and youth: the Colorado experience. American Journal of Public Health 90:1861–1865, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Catalano R, Satariano W: Unemployment and the likelihood of detecting early-stage breast cancer. American Journal of Public Health 88:586–590, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Catalano R, Lind S, Rosenblatt A, et al: Unemployment and foster home placements: estimating the net effect of provocation and inhibition. American Journal of Public Health 89:851–856, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Dickey D, Fuller W: Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Society 74:427–431, 1979Google Scholar

18. Box G, Jenkins G, Reinsel G: Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control. London, Prentice-Hall, 1994Google Scholar