Age of Gambling Initiation and Severity of Gambling and Health Problems Among Older Adult Problem Gamblers

Abstract

This study examined the relationship between age at first gambling experience and severity of gambling and related problems among older adult problem gamblers. Fifty-two problem gamblers over the age of 65 years completed self-report instruments that assessed gambling problems as well as the Short Form 36 health survey. The median age at first gambling experience was 21 years. Compared with gamblers who had a late onset of gambling, those with an early onset wagered more frequently and had more severe medical and psychiatric problems. These data suggest that gambling that begins in adolescence may be associated with an elevated severity of problems throughout the life span among older adult problem gamblers.

Pathological gambling is characterized by severe gambling problems, including preoccupation and loss of control. Its subdiagnostic threshold condition—problem gambling—is associated with moderate difficulties. A meta-analysis revealed that about 5.4 percent of adults are problem or pathological gamblers (1).

Participation in gambling has increased with the legalization of gambling opportunities (1), especially among older adults (2). Problem gambling among older adults may be a cause for concern given the putative association between gambling, medical problems, and psychiatric problems (3). However, only a few studies have been conducted of correlates of gambling problems among older adults. These studies have been limited to treatment-seeking gamblers (4), and their results suggest a later age at onset of gambling initiation among older compared with younger adult gamblers.

Among today's youths, gambling begins at a young age, and early-onset gambling may be associated with later development of problem or pathological gambling (5). Alcohol abuse commonly occurs with such gambling (1,2,3). Age at onset of alcohol use is related to increased problems in adulthood (6); a similar effect may emerge with respect to gambling.

The study reported here examined the relationship between age at first gambling experience and psychosocial problems among older adult problem gamblers. Non-treatment-seeking and problem gamblers were included in the study to maximize the generalizability of the findings.

Methods

A total of 52 participants were recruited by using two methods. Fourteen participants responded to an advertisement stating, "People over age 60 who like to gamble needed for a health survey" and were screened over the telephone. The remainder were recruited through direct screening in waiting areas of medical clinics (ten participants) or in senior centers (28 participants) by using the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) (7). Participants were recruited between November 2000 and August 2002. More than 85 percent of individuals who were approached for screenings agreed to participate. The study inclusion criteria were age of at least 60 years, score of at least 3 on the past-two-months version of the SOGS, report of at least three gambling episodes per month, and expenditure of at least $60 on gambling per month in the previous two months. The exclusion criteria were active major psychiatric disorder (bipolar disorder or psychosis) and severe dementia. None of the participants who met the inclusion criteria were excluded, and no known eligible participants refused to participate. The institutional review board of the University of Connecticut approved this study.

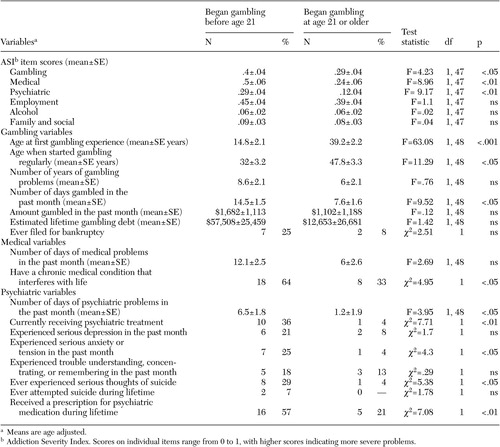

All participants completed the SOGS. SOGS scores greater than 5 indicate pathological gambling, and scoresof 3 or 4suggest problem gambling. The mean score in this sample was 4.3±.6, with a Cronbach's alpha of .78. The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (8) was also administered. This instrument assesses the severity of medical, employment, psychiatric, family and social, legal, alcohol, and drug problems in the previous month. Composite scores are derived; scores on individual items range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating more severe problems. In this study, a gambling section was also included (9). Participants also completed the Short Form 36 (SF-36) health survey, which provides two summary scores (physical health and mental health) and eight subscale scores. It has been validated for use among elderly persons (10). Possible scores on the SF-36 range from 0 to 160, with lower scores indicating greater severity of problems.

A median split procedure was used to divide gamblers into those with earlier initiation of gambling (younger than 21 years; 28 participants) and those with later initiation (21 years or older; 24 participants); t tests were used to compare groups on continuous variables, and chi square tests were used to evaluate categorical variables. Multivariate general linear models were used to evaluate group differences in ASI scores. Only six subscales were included, because composite scores in the legal and drug domains were zero for most study participants. Gender and age at initiation of gambling (earlier versus later) were entered as fixed factors and ASI composite scores as dependent variables. Because age may be associated with health variables, this variable was entered as a covariate. Similar results were obtained when gender and age were not included; in the interest of parsimony, only adjusted scores are shown here. For composite scores that differed between groups, subsequent analyses evaluated individual items, again controlling for age.

Results

The two groups did not differ in terms of demographic characteristics. In both groups, the mean±SD age of the participants was 67±7 years, the mean level of education was 14±3 years, and the mean income was $35,054± 23,121. In the full sample, 23 participants (44 percent) were married and 11 (21 percent) were widowed. Fifty participants (96 percent) were white.

In the multivariate analysis, age at gambling initiation was significantly associated with ASI score (F=2.94, df= 6, 42, p<.05), after current age and gender had been controlled for. Compared with participants who had a late onset of gambling, those with an early onset had higher ASI gambling, medical, and psychiatric scores, as can be seen in Table 1. On individual variables, participants with an early onset of gambling, in addition to beginning wagering regularly at a younger age, also reported wagering more frequently in the previous month. Those with an early onset of gambling were more likely to gamble on card games (15 participants, or 54 percent, compared with five participants, or 21 percent; χ2=4.55, df=1, p<.05) and on sports (11 participants, or 43 percent, compared with zero participants; χ2=3.9, df=1, p<.05). No differences in other gambling preferences were observed (data not shown). Compared with participants who reported a late onset of gambling, those with an earlier onset were more likely to have a chronic medical condition, to be receiving psychiatric treatment, and to report psychiatric symptoms.

Significant between-group differences were noted in physical health summary scores on the SF-36 (F= 4.61, df=1, 49, p<.05), with age-adjusted scores of 46.4±2.2 for those with an early onset of gambling and 53.2±2.3 for those with a late onset. Age-adjusted mental health summary scores were not significantly different between groups, at 53.4±2.1 and 50.4± 2.2, respectively. On subscales, participants with an early onset had lower scores (data not shown) on the physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, social functioning, and mental health domains (F=6.15, 4.96, 4.41, 4.85, 5.16, respectively; df=1, 49, p<.05).

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study indicate that older adult problem gamblers who began gambling earlier in life gambled more often than did their counterparts who began gambling as adults. The two groups also differed in their frequency of betting on sports and card games. Given that these types of gambling are common in nonlegalized venues, the propensity of gamblers with an early onset of gambling to wager on these activities may be related to their early participation in these activities, before the widespread legalization of gambling.

Scores on the ASI and the SF-36 suggest that participants with early-onset gambling had more severe health difficulties than did those with a later onset. Those with an early onset were twice as likely as those with a late onset to have a chronic medical condition, and they endorsed poorer functioning on measures of general physical health. Physically ill individuals may be drawn to sedentary gambling activities, and gambling may be a coping mechanism among older adults who are socially isolated and who have failing health. Alternatively, problem gambling may lead to inactive lifestyles. However, cross-sectional designs such as the one used in this study cannot be used to confirm these possibilities.

Participants with an early onset of gambling also reported greater psychiatric problems over the course of their lifetimes and at the time of the interview. Problem and pathological gambling have been associated with a variety of psychiatric conditions in previous research (3). The results of this study strengthen these earlier findings by suggesting that psychiatric difficulties may occur throughout life among persons who begin gambling while young. Surprisingly, no differences in substance use problems were noted between the two groups of gamblers. Problem gambling has been highly associated with alcohol and drug use among today's youths (1,2,3,4,5). Few participants in this study reported any illicit drug use, perhaps because they grew up during a time when drug use was not common. However, we did not collect detailed histories of substance use in this sample.

The findings of this study are limited by a number of issues. The results are based on self-reports of events that may have occurred 40 years previously. Although this is one of the first studies to specifically address older adult problem gamblers (4), the sample was small and primarily Caucasian. However, the fact that a non-treatment-seeking sample was recruited maximizes the generalizability of the findings to older problem gamblers.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants RO1-MH-60417, RO1MH-60417-suppl, RO1-DA-13444, RO1-DA-14618, P50-AA-03510, P50-DA-09241, and P60-AG-13631 from the National Institutes of Health as well as by the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation Investigator Program. The authors thank Yola Ammerman, Sabrena Davis, and Heather Gay for their assistance with data collection and management and George Ladd, Ph.D., and Gerard Kerins, M.D., for their assistance with the study.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington. Send correspondence to Dr. Petry at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Connecticut Health Center, 263 Farmington Avenue, Farmington, Connecticut 06030-3944 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic, clinical, and gambling characteristics of 52 older adult problem gamblers

1. 1Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J: Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: a research synthesis. American Journal of Public Health 89:1369–1376, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Gerstein D, Hoffmann J, Larison C, et al: National Opinion Research Council: Gambling Impact and Behavior Study. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1999Google Scholar

3. Cunningham-Williams RM, Cottler LB, Compton WM, et al: Taking chances: problem gamblers and mental health disorders: results from the St Louis Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. American Journal of Public Health 88:1093–1096, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Petry NM: A comparison of young, middle-aged, and older adult treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Gerontologist 42:92–99, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Botzet A, et al: A prospective study of youth gambling behaviors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 16:3–9, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, et al: Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:745–750, 2000Link, Google Scholar

7. Lesieur HR, Blume SB: The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1184–1188, 1987Link, Google Scholar

8. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al: New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 173:412–423, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Petry NM: Validity of a gambling scale for the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:399–407, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lyons RA, Perry HM, Littlepage BN: Evidence for the validity of the Short-form 36 Questionnaire (SF-36) in an elderly population. Age and Aging 23:182–184, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar