Economic Grand Rounds: Financing the Care of Individuals With Serious Mental Illness

A crisis in funding psychiatric services looms over practice and service systems, with a growing body of evidence showing that a systematic defunding of mental health care has occurred over the past several years (1). The economic downturn that began in 2000 accelerated this decline as states, which are a principal source of funding for the care of individuals with severe mental illness, experienced enormous budget deficits. One study found that when budgets are adjusted for inflation, states spend less on mental health care now than they did in 1955 (2). In response to annual and substantial increases in states' Medicaid costs, states are moving to restrict eligibility and benefit packages and are freezing reimbursement rates to providers (3).

The funding for mental health care that is received by seriously ill individuals comes from a complex and seemingly impenetrable array of sources with confusing eligibility rules and particular benefit packages. In an effort to make this critical topic more easily understood, this column provides an overview of the fiscal landscape and identifies the problems in funding mental health care for individuals with serious mental illness. The column concludes by highlighting the implications of such a system and the reasons for action and advocacy.

Understanding the sources of funding

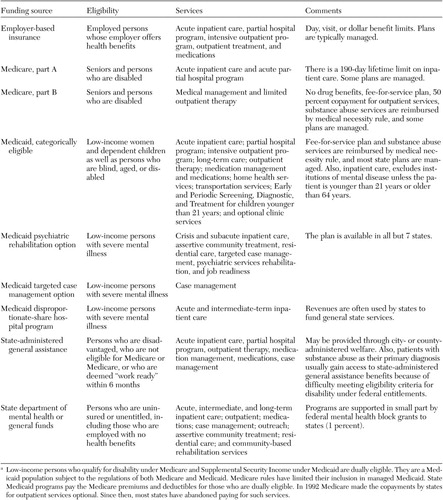

Two approaches come to mind for examining the multiple payers for treatment and rehabilitation services for individuals with serious mental illness. The first approach, outlined in Table 1, identifies each funding source, the groups eligible for coverage, and the types of services eligible for reimbursement. The second approach, outlined in Table 2, lists the levels of service and their funding sources. Ultimately, the problems caused by the multiplicity and limitations of funding sources are best understood through the lens of individuals who have had difficulty obtaining or maintaining needed services. We developed several case vignettes taken from our community mental health center (available from the authors on request), which, with the information from the two tables, illustrate how the existing patchwork of funding can impede the delivery of services to seriously ill persons as a function of age, socioeconomic drift, income or asset levels, living arrangements, maternal status, interstate travel, employment status, and entry to or departure from the criminal justice system.

Problems in financing

Overall, it appears that the multiple payers and the changing eligibility status of individuals lead to discontinuity of care and, in some cases, fragmentation of care—that is, the loss of part or all of a treatment program. This impression echoes the central conclusion of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health on the fragmentation of the service system for the seriously ill person (4). Some benefit packages, such as Medicare, omit essential levels of care for individuals with serious mental illness. Only Medicaid and state-funded services systematically fund outreach and case management to prevent relapse. Rehabilitation services are not financed by Medicare and are not covered comprehensively by all states under Medicaid. Housing and support services, which are often essential to the recovery of the seriously ill patient, are funded mainly outside of the medical insurance system, and individuals with serious mental illness are not always a priority. Although the services of the states' departments of mental health are a presumed safety net for gaps in service, they are increasingly rationed as state-funded agencies, which have been hard hit by state budget crises, carefully scrutinize the payer status of applicants and serve only those who have no alternative source of funding.

Although there may be initiatives from the federal government and through the states to address fragmentation in the organization of services, we believe the system of financing services will not dramatically change in the near future. Hence there is a need to advocate for improvements in existing funding sources.

Some future directions for advocacy

On the most global level, there is a need to advocate for parity of health insurance benefits for all psychiatric patients under all payers. Also, specific action plans for each payer are necessary, such as initiatives to eliminate discriminatory copayments for psychiatric services under Medicare.

Several other ideas for advocacy exist, including timely Medicare and Medicaid eligibility determination and reinstatement, which should begin before release from long-term hospitalization or prison. The institutions of mental disease exclusion under Medicaid could be revoked, which would better support state and county hospitals and staunch the flow of seriously ill patients into nursing homes. Reasonable Medicaid and Medicare rate structures could be created for the reimbursement of outpatient, clinic, and rehabilitative services to support an ample, high-quality system of care. A responsible pharmacy benefit management system that promotes good patient outcomes could be instituted. Requirements for clinical quality management could be implemented (in contrast to fiscal quality requirements, which already exist) in fee-for-service Medicaid and throughout all publicly funded services, particularly in times of fiscal stringency. Purchasing of services could be collaborative among federal, state, and private agencies to create comprehensive benefit packages. The income and asset limits that determine program eligibility could be raised. Optional Medicaid benefits, such as psychosocial rehabilitation and targeted case management, could be included for states that pursue benefit expansions under a Health Insurance Flexibility and Accountability waiver. Graduated mechanisms for cost sharing could be created, such as premiums, copayments, and fiscal management structures that help ensure appropriate service use. Alternative reimbursement structures to support progressive and efficient clinical practice could be created. Adequate ambulatory alternatives to institutional care could be implemented.

In the disability arena we need to refine definitions of eligibility to better address psychiatric impairment, monitor the process of disability determination under Social Security to ensure that it is not decentralized and deprofessionalized, introduce best practices into vocational rehabilitation services, and advocate for expansion of the Medicare benefit—beyond hospital, physician, and traditional clinic services into a broader range of professional and rehabilitative services, with cost sharing to mitigate the expenses of program growth. Also, it would help to advocate for more research on rehabilitative services—particularly in the Bureau of Vocational Rehabilitation—to establish a solid evidence base for this broad range of practices.

These ideas are neither exhaustive, nor presented in order of priority or opportunity, nor applicable in every state, which will be an essential site of advocacy. These ideas are intended to illustrate how a better understanding of the mechanisms for funding psychiatric services for individuals with serious mental illness can generate ideas for action.

More important in the long run is a renewed commitment by professional mental health workers to monitor and analyze the problems that have been created by existing funding as well as to mount initiatives on the funding of psychiatric services for seriously ill persons. As we develop more understanding and experience, the stage will be set for more informed and sophisticated policy development, communication, and advocacy by individuals and organizations.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Yale University and the Connecticut Mental Health Center, Room 168, 34 Park Street, New Haven, Connecticut 06519 (e-mail, [email protected]). Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Eligibility and covered services for persons with serious mental illness, by funding sourcea

a Low-income persons who qualify for disability under Medicare and Supplemental Security Income under Medicaid are dually eligible. They are a Medicaidpopulation subject to the regulations of both Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare rules have limited their inclusion in managed Medicaid. StateMedicaid programs pay the Medicare premiums and deductibles for those who are dually eligible. In 1992 Medicare made the copayments by statesfor outpatient services optional. Since then, most states have abandoned paying for such services.

|

Table 2. Levels of service for persons with serious mental illness and funding sourcesa

a The table does not include substance abuse services. Specialized services, rehabilitation, and medicationsfor persons with severe mental illness are not paid for by Medicare and commercial insurance.Vocational rehabilitation is not directly supported by Medicare or Medicaid.

1. Applebaum P: Response to the presidential address—the systematic defunding of psychiatric care: a crisis at our doorstep. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1638–1640, 2002Link, Google Scholar

2. Disintegrating Systems: The State of States' Public Mental Health Systems. Washington, DC, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, 2001Google Scholar

3. Holohan J, Weiner JM, Bovbjerg RR, et al: The State Fiscal Crisis and Medicaid: Will Health Programs Be Major Budget Targets? Washington, DC, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2003Google Scholar

4. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Rockville, Md, New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar