A Review of the Costs of Telepsychiatry

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The issue of whether telepsychiatry is worth the cost or whether it pays for itself is controversial. This study investigated this question by reviewing telepsychiatry literature that focused on cost. METHODS: Approximately 380 studies on telepsychiatry published from 1956 through 2002 were identified through MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and cross-referenced bibliographies. Of these, 12 studies with samples of more than ten persons or programs focused specifically on the cost of telepsychiatry. RESULTS: The methods of examining cost used in the 12 studies were cost-feasibility, cost surveys, direct comparison of costs of telepsychiatry and in-person psychiatry, and cost analysis. It was concluded that in seven of the studies reported, telepsychiatry was worth the cost. One study reported that telepsychiatry was not financially viable. Three studies of cost-effectiveness reported the break-even number of consultations, the number that make telepsychiatry comparable in cost to in-person psychiatry. One review concluded that the lack of a clear business plan contributed to the difficulty of determining whether any of the programs was cost-effective. CONCLUSIONS: Telepsychiatry can be cost-effective in selected settings and can be financially viable if used beyond the break-even point in relation to the cost of providing in-person psychiatric services. Whether governmental or private health agencies value telepsychiatry enough to assume its cost is a question that remains to be answered.

Telepsychiatry has been in existence for more than 40 years, yet the issue of whether it is worth the cost, or whether it even pays for itself, remains controversial. Whitten and associates (1) recently concluded, after an extensive review of the literature, that "there is no good evidence that telemedicine is a cost-effective means of delivering health care." We reviewed the literature on the cost of telepsychiatry to determine whether telepsychiatry is worth the cost.

The basic components of telepsychiatry costs can be classified as direct costs—including the cost of equipment, lines for information transmission, operation of the telepsychiatry system, supplies, maintenance, and the salary of the telecommunications coordinator—and indirect costs, including transportation of patients and clinicians to the telepsychiatry site and administrative overhead costs. Hidden costs include training individuals in the use of the equipment, maintaining duplicate records at several sites, transmitting clinical information between sites, and allocating space for equipment. In this article we note discussions of component costs in the studies reviewed. We summarize findings of the studies about costs, derived both from actual services delivered and from theoretical calculations, and about cost comparisons between telepsychiatry and in-person psychiatric services. The methods and limitations of each study are also noted.

The cost-related terms used in the articles reviewed—for example, cost, cost-effectiveness, and cost-benefit—are defined elsewhere (2,3,4,5).

Methods

Published studies were identified through English-language searches of MEDLINE and PsycINFO databases from 1956 through 2002 using the terms "telepsychiatry," "telemedicine + psychiatry," "teleconferencing + psychiatry," "cost," "cost analysis," "cost-benefit," "cost-effectiveness," and "cost-consequences matrix." Studies were also found in bibliographies provided by the authors of two recent literature reviews (6,7). The studies we found were grouped by their method of looking at cost and were tabulated accordingly.

Results

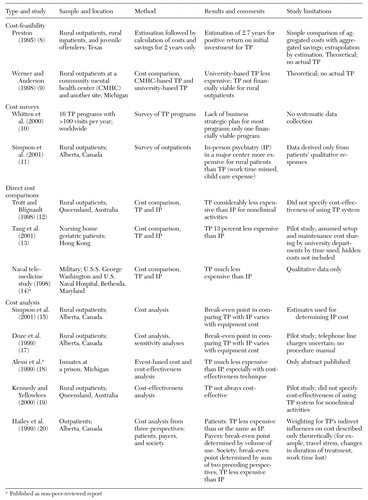

Although more than 380 articles relating to telepsychiatry were found, the literature search generated only 12 articles that focused specifically on the cost of telepsychiatry; ten of those were peer reviewed. The articles appeared from 1995 through 2002. The projects described in the studies were located in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Hong Kong, and one study included programs around the world. Table 1 summarizes the 12 studies reviewed.

Cost-feasibility

Two articles used a cost-feasibility method, calculating costs theoretically, with no actual service delivered (8,9). Preston (8), in 1995, reported on an assessment of the potential savings of a rural telemedicine project that included a telepsychiatry component. The authors estimated that a positive return on investment would take approximately 2.7 years. Werner and Anderson (9), in 1998, reported their study of the cost-feasibility of implementing a telepsychiatry system called university-based telepsychiatry to link psychiatrists at Michigan State University with patients at a rural community mental health center (CMHC). The authors compared this type with one called CMHC-based telepsychiatry that used a link between the CMHC and another rural site. The university-based system was found to be less expensive, chiefly because of the preexistence at the university of integrated services digital network (ISDN) lines. The authors concluded that although "telepsychiatry is technologically feasible, it is pragmatically difficult, and not economically supportable in providing services to remote rural areas at this time."

Cost surveys

Two articles used surveys as a way to subjectively probe cost without determining it objectively (10,11). During 1998 and 1999, Whitten and colleagues (10) surveyed 16 U.S. and international programs that had each conducted at least 100 consultations by telepsychiatry. Only one program reported that it was self-sustaining through revenues from service delivery. The authors identified a need for better financial planning for delivering telepsychiatry services cost-effectively. Simpson and colleagues (11) reported in 2001 that the availability of telepsychiatry led to cost savings for patients who would otherwise have had to travel and thus lose time at work and pay child care expenses.

Direct comparisons of costs

Three studies directly compared the costs of telepsychiatry with those of in-person psychiatry (12,13,14). Trott and Blignault (12), in 1998, reported their calculations of travel savings obtained through the use of telepsychiatry compared with the same level of service provided in person over one year. The child and adolescent teleconsultation component proved to be the highest generator of savings. These savings persisted even after the capital costs associated with the establishment of the telepsychiatry system and the costs of the telepsychiatry calls were taken into account. No maintenance and equipment upgrading costs were considered by Trott and Blignault. Tang and associates (13), part of the psychogeriatric team of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, reported in 2001 on telepsychiatry for nursing home geriatric patients. The authors found that the cost of telepsychiatry was 13.2 percent lower than that of an in-person visit when the setup and maintenance costs were shared by various departments of the university according to the proportion of time they used the system. In 1998 The U.S. Navy reported on a telepsychiatry project that connected the aircraft carrier U.S.S. George Washington with the U.S. Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland (14). It was determined that telepsychiatry reduced the costs of psychiatric intervention both directly, by cutting the high cost of patient evacuation by air from the sea, and indirectly, by ensuring a rapid intervention that maintained the psychological balance and the functional capacity of both patient and colleagues on board.

Cost analysis

Cost analysis is an objective, more sophisticated method of looking at cost-effectiveness (15,16,17,18,19). A cost analysis "examines what costs are associated with a particular [proposed] project and what may be done about those costs in the future" (16).

In a follow-up to the article by Simpson and colleagues (11) discussed above, the same authors pointed out in 2001 that the high cost of many in-person mental health services could prohibit their delivery, ultimately decreasing the revenue of the health care provider (15). Similar results were found by Doze and associates (17), who reported in 1999 that telepsychiatry was more expensive than in-person psychiatry at a low volume of service but less expensive at a higher volume. As part of their study, the authors analyzed the degree to which economic viability would change with the values of variables. For example, in considering the break-even point—the point at which telepsychiatry is comparable in cost to in-person psychiatry—the authors found that a reduction of 10 percent in equipment cost reduced the break-even point from 396 to 368 telepsychiatry consultations a year. Doze and associates concluded that in some scenarios the use of telepsychiatry might justify costs that remained below the break-even point and that cost analysis should not be the only factor considered by health service decision makers.

Alessi and colleagues (18) reported in 1999 on two economic analyses of a prison telepsychiatry service. The first analysis was event based and focused on the costs of transportation. The second analysis measured cost-effectiveness by the time spent by health and prison professionals. A comparison of these two techniques demonstrated substantial cost savings through telepsychiatry, especially when the cost-effectiveness analysis was used.

Kennedy and Yellowlees (19) reported in 2000 that cost-effectiveness could not be determined solely by examining the financial cost but also required examining health outcomes, utilization, accessibility, quality, and needs for such services in the specific population studied. These authors reported that a community-based telepsychiatry program was not necessarily cost-effective for all consumers, general practitioners, psychiatrists, and public mental health services. Hailey and associates (20) published a cost analysis in 1999 comparing telepsychiatry and in-person psychiatry and presented results from three different perspectives. For patients, telepsychiatry was less expensive than in-person psychiatry because of reduced travel costs. For third-party payers, telepsychiatry was initially more expensive than in-person psychiatry, but an increase in the volume of use resulted in telepsychiatry's becoming less expensive. From the societal perspective, an approximate sum of the other two perspectives, telepsychiatry was less expensive.

Discussion

We concluded that in seven of the 12 studies dealing with the cost of telepsychiatry, telepsychiatry was worth the cost (8,11,12,13,14,15,18). One study determined that telepsychiatry was not financially viable for rural outpatients (9). Three studies of cost-effectiveness reported on the break-even number of consultations—the point at which the cost of telepsychiatry becomes equivalent to that of in-person psychiatry (15,17,20). One review surveying 16 telepsychiatry programs concluded that the lack of a clear business plan contributed to the difficulty of determining whether any of the programs was cost-effective (10).

Limitations

Limitations of this review are the small number of studies available, their weak methodologies, the lack of explicitly presented sources of funding, the lack of consistency in presentation of costs, and the noncomparability of the cost factors across the 12 studies, as can be seen in Table 1. In addition, several studies were at least five years old, meaning that their findings and conclusions could now be different because of the rapid pace of technological change. Finally, in reports of most of the studies, the authors appeared to have a vested interest in the success of the telepsychiatry program at their institution; thus the conclusions may not be objective.

A formal meta-analysis of the cost of telepsychiatry would require at least several studies with independent reviewers, random assignment, matched controls, objective outcome measures, and a comprehensive analysis of the influences of sources of funding and indirect cost-related issues on costs. Not addressed by most of the studies reviewed were issues of outcome and efficacy, which still need to be studied.

Is telepsychiatry worth the cost?

One question in determining whether telepsychiatry is worth the cost is "Does telepsychiatry cost more or less than in-person psychiatry?" The answer is that it depends on many factors, including the price of the equipment and the transmission costs, whether the equipment cost is borne exclusively by the telepsychiatry program or shared by other programs (for example, other specialties or administrative programs), the cost of technical support, how far the treating psychiatrist travels to conduct in-person treatment compared with the cost of support staff for telepsychiatry at the site where the patient is located, the volume of cases treated, and the reimbursement rate.

Last, the answer depends on the party paying the costs. For patients, telepsychiatry can be less expensive in that it requires less travel time to see specialists. On the other hand, insurance companies might be concerned that their costs will increase as a result of an increase in the use of services made possible by telepsychiatry. From the perspective of the health care provider, the break-even analysis—which considers the volume of use needed to equalize the total costs for the two types of service (15,17,20)—shows that at higher volumes, telepsychiatry is less costly. Analysis from a societal perspective, in which fixed and variable costs per patient for each alternative are calculated, takes into account costs incurred by the patient as well as the health care provider (20).

A cost-consequences matrix includes costs for and benefits to specialists, referring physicians, health care professionals, patients and their families, and health care administrators and funders (21); consideration is then given to providing appropriate weightings for intangible benefits in association with those that have monetary valuations. With telepsychiatry, access to certain services might increase appreciably, with benefits to the health of a population but at additional cost.

Funding issues

The majority of telepsychiatry programs worldwide still remain grant funded. Many of them face the imminent step of finding ongoing revenue streams to sustain them. These programs must show that they are cost-effective if they are going to survive (22). Rapid changes in technology, such as decreases in equipment and transmission costs and the increased reliability of equipment, as well as the sharing of expenses between disciplines, can be expected to continue to change the cost-benefit equation in the direction of decreased cost and increased benefit (6,23,24).

An important economic issue in the United States in geriatric settings is the status of Medicare reimbursement for telemedicine services (25). Because insurance companies often mirror Medicare reimbursement practice, such practice has implications beyond the geriatric population. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, formerly the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), published rules and regulations in November 1998 for Medicare reimbursement of telemedicine services; more recent legislation approved significant modifications in these original rules, beginning with October 2001. A "referring clinician" is no longer "medically necessary" at the patient site. The requirement that the reimbursement be split with the referring clinician has also been dropped. The ability to bill for "teleconsultation" continues to be restricted geographically but has been broadened to include Medicare beneficiaries residing in rural areas with shortages of health professionals, counties that are not included in a metropolitan statistical area, and agencies participating in federal telemedicine demonstration projects (25).

The cost of telepsychiatry must also be considered in light of whether it would draw funding away from other services. Because the budget for many communities is fixed, the allocation of money for telepsychiatry may result in less money for other endeavors. Decisions will need to be made by local administrators about whether telepsychiatry provides enough "bang for the buck" compared with delivering other services.

Conclusions

From a review of the recent literature on the cost of telepsychiatry—even given the limitations of many of the studies—we conclude that telepsychiatry can be cost-effective in selected settings. However, there is no assurance that any governmental or private health care agency will be willing to assume the cost. The cost of telepsychiatry should be considered in relation to how it contributes to improving the health of the population through access to information and communication and how it changes the types of interaction between providers themselves and between providers and their patients (26).

Telepsychiatry's ultimate survival will depend on its finding its niche. Future telepsychiatry might be part of a hybrid—distinct from current health care systems. In one possible model of care, initial comprehensive evaluations could be conducted in person and routine follow-up visits through telepsychiatry. When the alternative to telepsychiatry is no psychiatry, whether psychiatry is worth the cost will depend on the value placed on delivering psychiatric services at all.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Columbia University in New York City. Dr. Hyler is also with the department of psychiatry at New York State Psychiatric Institute, and Dr. Gangure is also with St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York City. Send correspondence to Dr. Hyler at Box 130, NYSPI, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, New York 10032 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Summary of 12 studies focusing on issues of cost in telepsychiatry (TP)

1. Whitten PS, Mair FS, Haycox A, et al: Systematic review of cost effectiveness studies of telemedicine interventions. BMJ 324:1434–1437, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Berger ML, Teutsch SM: Understanding cost-effectiveness analysis. Preventive Medicine in Managed Care 1:51–58, 2000Google Scholar

3. Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, et al (eds): Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

4. Garber AM, Weinstein MC, Torrance GW, et al: Theoretical foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis, in Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Edited by Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, et al. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

5. Eddy DM: Benefit language: criteria that will improve quality while reducing costs. JAMA 275:650–657, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Baer L, Elford L, Cukor P: Telepsychiatry at forty: what have we learned? Harvard Review of Psychiatry 5:7–17, 1997Google Scholar

7. Frueh BC, Deitsch SE, Santos AB, et al: Procedural and methodological issues in telepsychiatry research and program development. Psychiatric Services 51:1522–1527, 2000Link, Google Scholar

8. Preston J: Texas Telemedicine Project: a viability study. Telemedicine Journal 1:125–132, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Werner A, Anderson LE: Rural telepsychiatry is economically unsupportable: the Concorde crashes in a cornfield. Psychiatric Services 49:1287–1290, 1998Link, Google Scholar

10. Whitten P, Zaylor C, Kingsley C: An analysis of telepsychiatry programs from an organizational perspective. Cyberpsychology and Behavior 3:911–916, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Simpson J, Doze S, Urness D, et al: Telepsychiatry as a routine service: the perspective of the patient. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 7:155–160, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Trott P, Blignault I: Cost evaluation of a telepsychiatry service in northern Queensland. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 4(suppl 1):66–68, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

13. Tang WK, Chiu H, Woo J, et al: Telepsychiatry in psychogeriatric service: a pilot study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 16:88–93, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Naval telemedicine: fleet lines up to provide live teleconsulting; telepsychiatry saves time and money on the high seas. Telemedicine and Virtual Reality 3(4):40, 47, 1998Google Scholar

15. Simpson J, Doze S, Urness D, et al: Evaluation of a routine telepsychiatry service. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 7:90–98, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Shin JK, Siegel JG: Modern Cost Management and Analysis, 2nd ed. Hauppauge, NY, Barron's Educational Series, 2000Google Scholar

17. Doze S, Simpson J, Hailey D, et al: Evaluation of a telepsychiatry pilot project. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 5:38–46, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Alessi NE, Rome L, Bennett J, et al: Cost-effectiveness analysis in forensic telepsychiatry prisoner involuntary treatment evaluations (abstract). Telemedicine Journal 5:17, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Kennedy C, Yellowlees P: A community-based approach to evaluation of health outcomes and costs for telepsychiatry in a rural population: preliminary results. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 6(suppl 1):155–157, 2000Google Scholar

20. Hailey D, Jacobs P, Simpson J, et al: An assessment framework for telemedicine applications. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 5:162–170, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. McIntosh E, Cairns J: A framework for the economic evaluation of telemedicine. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 3:132–139, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Darkins A: Program management of telemental health care services. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 14:80–87, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. May C, Gask L, Atkinson T, et al: Resisting and promoting new technologies in clinical practice: the case of telepsychiatry. Social Science and Medicine 52:1889–1901, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Bashshur RL: Telemedicine effects: cost, quality, and access. Journal of Medical Systems 19:81–91, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Jones BN 3rd, Ruskin PE: Telemedicine and geriatric psychiatry: directions for future research and policy. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 14:59–62, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Bashshur RL, Sanders JH, Shannon GW: Telemedicine: Theory and Practice. Springfield, Ill, Charles C Thomas, 1997Google Scholar