Behavioral Health Screening Policies in Medicaid Programs Nationwide

Abstract

Under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) mandate, states are required to screen Medicaid-insured children for mental health and substance use disorders. This national study found that states vary considerably in their policies. Nearly half the states (23 in total) have not addressed behavioral health issues in their EPSDT screening tools at all. More states have screening tools that address mental health than substance use disorders. Most states have created their own screening tools, which suggests discomfort with or a lack of awareness of the standard tools available. Screening policy options to increase behavioral health screening rates are discussed.

Almost 21 percent of children and adolescents have a diagnosable mental disorder, and 11 percent have significant impairment as a result. An estimated 70 percent of children with mental health conditions do not receive specialty mental health services (1). These bleak statistics explain why the U.S. Surgeon General's National Action Agenda for Children states as its primary concern "promoting the recognition of mental health as an essential part of child health." Children who are insured by Medicaid and who are eligible because of low socioeconomic status or significant disability are more likely to need mental health care.

Likewise, a large number of youths with substance use problems do not receive treatment. In 2001, one million adolescents needed but did not receive treatment for illicit drug use (2). Given the prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders among children, the early identification of these conditions should be a high priority for Medicaid.

Federal Medicaid laws and regulations recognize this need for early identification. Under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) mandate, children and adolescents—that is, those under the age of 21 years—are to be screened for mental health conditions, including substance use disorders, as a regular component of comprehensive medical assessments (3). These Medicaid screenings consist of a health and developmental history, an unclothed physical examination, immunizations and laboratory tests, and health education. The purpose is to diagnose health conditions early, "before they become more complex and their treatment more costly," and to refer children to treatment. In July 1990, the Health Care Financing Administration—now known as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services—set a nationwide target that 80 percent of children who are insured by Medicaid receive an EPSDT screening annually.

Given that primary care physicians rather than behavioral health specialists usually have the responsibility for conducting EPSDT screenings, states can improve the identification of behavioral health conditions by requiring that children be screened for these conditions and by providing the most effective screening tools. Individual state Medicaid agencies have the authority to decide how to ensure that children and adolescents are screened for mental health and substance use problems during EPSDT screenings. Few studies have examined the policies that state Medicaid agencies have adopted to fulfill the required mental health and substance abuse screening (4,5).

Methods

To determine current behavioral health screening policies in Medicaid programs, EPSDT screening tools were collected from Medicaid agencies and state mental health authorities in all 50 states and the District of Columbia between June 2000 and January 2001. All states responded.

The screening tools were categorized into two types. The first type included specialized behavioral health screening tools consisting of extensive questions about mental health or substance abuse to be asked during visits for EPSDT screening. Typically, these are stand-alone tools, separate from the comprehensive screening tools that are used to identify physical health problems. The second type includes comprehensive screening tools for physical and developmental issues that may or may not include prompts or brief questions about behavioral health. When included in comprehensive tools, behavioral health is usually briefly addressed.

For the purposes of this study we did not consider developmental screening or mental health diagnostic tools to be mental health screening tools. Although several states recommend instruments for assessing developmental issues, particularly for young children aged zero to six years, none of these instruments were found to adequately identify mental health problems. In addition, one state recommends the use of the Child Behavioral Checklist, but this instrument is more appropriate for the diagnosis of mental health conditions than for general screening.

Results

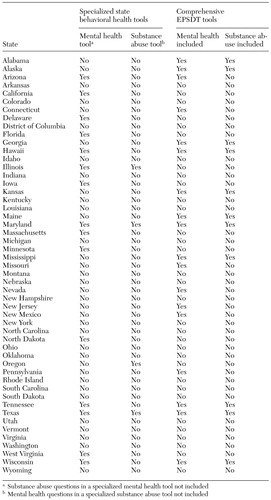

States vary considerably in their behavioral health screening policies (Table 1). More than half the states (a total of 28) recommend screening tools that reference behavioral health to some degree, either in specialized behavioral health tools or in comprehensive EPSDT screening tools. The remaining 23 states (45 percent) have no specialized behavioral health screening tools and no behavioral health questions or prompts in their comprehensive screening tools.

States appear to have no preference between specialized tools and comprehensive ones. About the same number of states reference behavioral health in specialized tools (16 states) as in comprehensive screening tools (18 states).

States are more likely to reference mental health than substance use disorders. Fifteen states have specialized mental health tools, compared with four states with specialized substance abuse tools. Eighteen states have comprehensive screening tools that reference mental health, compared with 11 that reference substance abuse.

Most states recommend, rather than require, that primary care providers use specific tools. Although 15 states (31 percent) have specialized mental health screening tools, only one state (West Virginia) and some counties in another state (California) mandate that providers use the specified tool. The other states that recommend a specialized mental health tool allow providers to decide whether to use that tool. None of the states require the use of a specialized substance abuse tool. Most states recommend or require their own mental health or substance abuse tools rather than standardized tools. About one-third of the states (five of 16) recommend or require a standardized mental health tool. One-quarter of the states (one of four) recommend or require a standardized substance abuse tool. Of the standardized mental health screening tools, the most commonly recommended is the Pediatric Symptom Checklist. For substance abuse screening, states recommend the CAGE Questionnaire and the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test.

The 31 specialized tools used by states to screen for behavioral health were assessed on three criteria that are important for providers using them and for families answering and completing them: rapid administration, clear referral criteria, and the individual who completes them. All the screening tools can be administered quickly and efficiently, with most being one or two pages in length. A total of 23 (74 percent) of the 31 specialized behavioral health screening tools provided clear referral criteria for identifying children in need of diagnosis and behavioral health services.

Most tools list risks, behaviors, and symptoms that identify the need for an immediate referral or treatment. Only a few are scored numerically. Providers administer nearly half (48 percent) of the screening tools. Most of the remaining tools are completed by the child (42 percent) or the parent (39 percent). Tools completed by the patient or the patient's family are more likely to be used in a busy office or clinic, because parents and older patients can complete the screening tool while waiting for the provider. (A complete list of the specialized behavioral health screening tools and the criteria assessment is available from the Bazelon Center.)

Discussion and conclusions

This review of Medicaid behavioral screening policies found that states vary considerably in their policies and that very few have policies in place that are likely to result in accurate identification of children with behavioral health disorders. Although more states address mental health than substance use disorders, nearly half the states (a total of 23) have not addressed behavioral health issues in their EPSDT screening tools at all.

Primary care providers in many states receive no guidance from Medicaid agencies on screening tools that accurately identify behavioral health problems. Studies have found that primary care providers lack mental health and substance abuse training (6) and that those who rely on their professional judgment alone fail to identify between 40 and 50 percent of children and adolescents who have mental health and substance use disorders (7,8). The use of specialized tools has been found to considerably increase rates of identification of behavioral health problems (9).

Specialized versus comprehensive screenings

States have policy options to consider for improving behavioral health screening under EPSDT. They can develop a separate, specialized behavioral tool or include a set of behavioral health checklists, prompts, and questions in a comprehensive screening tool. Separate specialized tools have advantages, because they result in more accurate assessment and referrals. Tools that are completed by the child's parent increase the likelihood that behavioral problems will be identified in a busy practice. However, inclusion of behavioral health problems in a comprehensive screening tool may have other advantages. A separate, specialized tool may be set aside or overlooked during some visits. An integrated tool encourages providers and families to think of behavioral health as just one more component of health care, not a separate issue.

Recognizing the advantages of both approaches, a small number of states—Arizona, Maryland, Hawaii, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin—have specialized behavioral health tools as well as comprehensive screening tools that include behavioral health. Additional research is needed to monitor and evaluate the impact of state Medicaid policies on behavioral health screening rates. Until more research is available, state polices that include both specialized and comprehensive screening tools appear to be the soundest course.

Use of standard tools

States have, for the most part, created their own screening tools, which suggests that they are unaware of or uncomfortable with the standard tools available. The Pediatric Symptom Checklist, the most commonly recommended standardized mental health screening tool, has been found in extensive studies to rarely misidentify children who do not have a behavioral problem (10). For substance abuse screening, none of the states recommend the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers, identified as the best standard adolescent screening instrument by a consensus panel of the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. The states recommend instruments that were developed for adults and do not focus on related functional areas, such as the CAGE Questionnaire or the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test.

The need for consensus

The effectiveness of screening could be improved if mental health and substance abuse professional organizations were to work with the American Academy of Pediatrics to develop a consensus on the best instruments for behavioral health screening of Medicaid-insured children. Policy makers, providers, advocates, and researchers could then provide technical assistance to ensure the use of these tools and evaluate their impact on screening children for behavioral health issues.

Acknowledgments

This article is based in part on information obtained by R.O.W. Sciences under contract with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The writing of this article was supported by contributions of the Public Welfare Foundation and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, which provides generous core support for the Bazelon Center's overall program.

Mr. Semansky is senior policy analyst and Ms. Koyanagi is policy director at the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, 1101 Fifteenth Street, N.W., Suite 1212, Washington, D.C. 20005 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Vandivort-Warren is senior public health analyst in the organization and financing branch of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in Rockville, Maryland. Versions of this paper were presented at the annual research conference—A System of Care for Children's Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base—held March 3 to 6, 2002, in Tampa, Florida, and at the annual conference of the American Public Health Association held November 12 to 16, 2000, in Boston.

|

Table 1. States' policies on Medicaid behavioral health and comprehensive Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) screening tools, 2001

1. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

2. Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume I: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002Google Scholar

3. Medicaid Managed Care and EPSDT. Washington, DC, Office of the Inspector General, 1997Google Scholar

4. An Evaluation of State EPSDT Screening Tools: Issue Brief 3. Washington, DC, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, July 1997Google Scholar

5. Stroul B, Pires S, Armstrong M: Tracking State Managed Care Reforms as They Affect Children and Adolescents With Behavioral Health Disorders and Their Families. Health Care Reform Tracking Project:2000 State Survey. Tampa, University of South Florida department of child and family studies, 2001Google Scholar

6. Wender EH, Bijur PE, Boyce WT: Pediatric residency training: ten years after the task force report. Pediatrics 90:876-880, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kelleher KJ, Childs GE, Wasserman RC, et al: Insurance status and recognition of psychosocial problems. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine 151:1109-1114, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Robinson J, et al: Pediatric Symptom Checklist: Screening school-age children for psychosocial dysfunction. Journal of Pediatrics 12:201-209, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Murphy JM, Ichinose C, Hicks RC, et al: Utility of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist as a psychosocial screen to meet the federal Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) standard: a pilot study. Journal of Pediatrics 6:864-869, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Canning EH, Kelleher K: Performance of screening tools for mental health problems in chronically ill children. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 148:272-278, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar