Near-Death Experiences in a Psychiatric Outpatient Clinic Population

Abstract

Near-death experiences, or mystical experiences during encounters with death, are reported to have beneficial effects despite their phenomenologic similarity to pathological states. This study explored the prevalence of near-death experiences and associated psychological distress by using a cross-sectional survey of 832 psychiatric outpatients. Standardized measures of near-death experiences and psychological distress were administered via questionnaire at clinic intake. A total of 272 patients (33 percent) reported encounters with death, and these patients were found to have greater psychological distress than other patients. Sixty-one of the patients who had been close to death (22 percent) reported having near-death experiences, and these patients were found to have less psychological distress than patients who did not have near-death experiences after brushes with death.

Coming close to death is a traumatic event that may lead to clinically significant psychological distress, decreased functional capacity, and a greater need for psychiatric services (1). Some encounters with death are accompanied by profound near-death experiences, which may include subjective impressions of being outside the physical body, visions of deceased relatives and religious figures, and transcendence of ego and spatiotemporal boundaries (2). Although near-death experiences have phenomenologic commonalities with pathological states, persons who have near-death experiences are psychologically indistinguishable from comparison populations (2).

Near-death experiences have been associated with enhanced purpose in life, appreciation of life, confidence, and self-esteem and with reduced fear of death (2), suicidal ideation (3), and posttraumatic stress symptoms (4). In light of the traumatic nature of encounters with death and the reputed beneficial effects of near-death experiences, this study was designed to assess psychological distress among patients who have had these experiences.

The study hypotheses were that psychiatric outpatients who had come close to death would report more psychological distress than those who had not come close to death and that patients who had had near-death experiences during an encounter with death would report less psychological distress than those who had not had such experiences. Using a cross-sectional survey of all patients presenting for intake in a psychiatric clinic over a one-year period, we explored the prevalence of encounters with death and of near-death experiences and examined the association between those events and a standardized measure of psychological distress.

Methods

The study participants were patients presenting for the first time to the University of Connecticut psychiatric outpatient clinic between July 1994 and June 1995. Patients who came to the clinic completed a computerized version of the revised 90-item Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) (5) at intake before a psychiatric interview. This computer screening took 15 minutes to complete and was intended to provide the evaluating psychiatrist with preliminary data about the patient's symptoms. During the one-year study period, 832 patients completed the computerized screening questionnaire. The number of patients who did not complete the questionnaire is unknown.

The SCL-90-R is a widely used measure of clinical function in which respondents rate items on a 5-point scale of distress ranging from 0, not at all, to 4, extremely. The instrument addresses nine symptom dimensions: somatization, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. The SCL-90-R also yields three global indexes of distress: the Global Severity Index, which is the total of all 90 items; the Positive Symptom Scale, which is the total number of items rated 1 or higher; and the Positive Symptom Distress Index (the Global Severity Index divided by the Positive Symptom Scale total). Higher scores on the indexes indicate more distress.

The computerized screening that followed administration of the SCL-90-R included the question, "Have you ever come close to death?" Patients who answered affirmatively were prompted to complete a computerized version of the 16-item Near-Death Experience Scale (NDE) (6). This scale includes questions about cognition, such as accelerated thoughts and a "life review"; affect, such as intense feelings of peace and joy; purportedly paranormal experiences, such as a feeling of being outside of the body and a perception of future events; and an experience of transcendence, such as encountering deceased relatives or an unearthly realm.

The NDE has acceptable internal consistency (alpha=.88), split-half reliability (alpha=.84), and test-retest reliability (alpha=.92) (6) and has been shown to be a unidimensional measure that differentiates near-death experiences from other stress responses, independent of time elapsed since the event (7). A score of 7 or higher out of a possible 32 was used as the standard criterion for a near-death experience, because this score is one standard deviation below the mean for a criterion group of persons who had a near-death experience (6).

The study was presented to the university's institutional review board, which determined that screening questionnaires given to all patients as part of a clinical intake procedure did not require either approval by the board or written informed consent from patients.

Raw SCL-90-R scores were converted to T scores and evaluated by using t tests for independent samples. As a measure of effect size, 95 percent confidence intervals are presented for the mean differences of all comparisons. All analyses were performed by using SPSS for Windows, version 10.1.

Results

Of the 832 patients, 272 (33 percent) reported having been close to death. Of these, 61 (22 percent) had had near-death experiences according to the NDE criterion, representing 7 percent of the patient population.

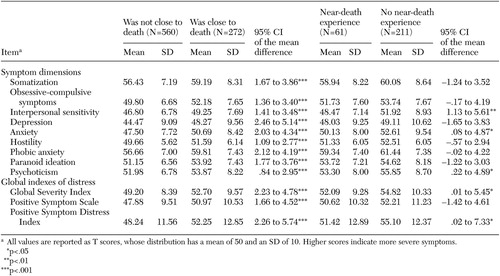

The SCL-90-R scores of patients who had and had not come close to death and who did and did not have near-death experiences are listed in Table 1. For each of the SCL-90-R symptom dimensions and global indexes of distress, scores were significantly higher among patients who had been close to death than among those who had not. Among the patients who had come close to death, scores on each of the SCL-90-R symptom dimensions and global indexes were better among those who reported near-death experiences than among those who did not. That difference was statistically significant for three of the symptom dimensions (interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, and psychoticism) and for two of the global indexes of distress (global severity and total positive symptoms).

Discussion

Among the patients in this study, having come close to death was associated with increased psychological distress. However, among those who had come close to death, near-death experiences were associated with less psychological distress.

The results of previous studies suggest that near-death experiences reduce suicidal ideation (3) and symptoms of posttraumatic stress (4). The study reported here further suggests that near-death experiences are associated with diminished global psychological distress among psychiatric patients who have faced death. The proportion of patients in this study who reported near-death experiences was comparable to that found in the general population (8), which suggests that mental illness itself bears no association with near-death experiences.

Studying an intact cohort of outpatients at clinic intake avoided investigator bias in selection of study participants. However, findings of associations between close brushes with death and increased psychological distress—and between near-death experiences and decreased psychological distress—do not establish a causal connection between these events and subsequent distress. It is conceivable that more severe psychopathology predisposes patients to take life-threatening risks or lowers the predisposition to have near-death experiences when encountering death. Furthermore, this study did not assess demographic and diagnostic variables that might confound associations between life events and psychological distress. Nor did it evaluate the influence of details of the encounter with death or of elapsed time since the encounter with death.

Conclusions

These data strengthen previous findings that encounters with death are traumatic experiences that may lead to subsequent suffering. The data also provide evidence that near-death experiences that occur during encounters with death are associated with decreased suffering. Psychological distress would plausibly be associated with decreased functional capacity and a greater need for psychiatric services. These findings suggest that a history of nearness to death and the subjective experiences surrounding such events may be relevant to current psychological distress and worthy of exploration by clinicians.

Dr. Greyson is affiliated with the department of psychiatric medicine at the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville. Send correspondence to him at the Division of Personality Studies, University of Virginia Health System, P.O. Box 80052, Charlottesville, Virginia 22908-0152 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Scores on the revised 90-item Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) among psychiatric outpatients at clinic intake

1. Van der Kolk BA, Pelcovitz D, Roth S, et al: Dissociation, somatization, and affect dysregulation: the complexity of adaptation to trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry 153 (suppl 7):83–93, 1996Google Scholar

2. Greyson B: Near-death experiences, in Varieties of Anomalous Experience: Examining the Scientific Evidence. Edited by Cardeña E, Lynn SJ, Krippner S. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2000Google Scholar

3. Greyson B: Near-death experiences and antisuicidal attitudes. Omega 26:81–89, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Greyson B: Posttraumatic stress symptoms following near-death experiences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 71:368–373, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Derogatis LR: SCL-90-R Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual-II. Towson, Md, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1992Google Scholar

6. Greyson B: The Near-Death Experience Scale: construction, reliability, and validity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 171:369–375, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lange R, Greyson B, Houran J: Establishing Near-Death Experiences as Core Experiences: A Rasch Scaling Perspective. Presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Scientific Exploration, Charlottesville, Va, May 29–31, 2002Google Scholar

8. Greyson B: The incidence of near-death experiences. Medicine and Psychiatry 1:92–99, 1998Google Scholar