Psychotic Ideation and Receipt of Government Entitlements Among Homeless Persons in New York City

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study compared changes in receipt of government entitlements by homeless persons with and without psychotic ideation in New York City between January 1997 and July 1998, a period characterized by changing state government policies and greater bureaucratic monitoring of eligibility. METHODS: In conjunction with an experimental study of the efficacy of social work services provided to homeless persons in Manhattan by a mobile medical van, 25 persons who were assessed as having experienced psychotic ideation in the previous year and 134 nonpsychotic persons were followed up after four months to identify changes in their receipt of Medicaid benefits, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), food stamps, and home relief (state welfare for single persons). The social work intervention was designed to help eligible clients gain access to entitlements and substance abuse treatment. RESULTS: The proportion of clients with psychotic ideation who received Medicaid, food stamps, or home relief decreased during the study period, while the proportion of nonpsychotic clients who received these entitlements increased. Little change was observed in receipt of SSI or SSDI by either group. CONCLUSIONS: Psychotic ideation among homeless persons may be a significant factor in access to and maintenance of government entitlements. In the context of an increasingly restrictive and bureaucratic welfare system, providing assistance to homeless persons who have severe psychopathology presents new challenges to service providers.

Access to government entitlements is often critical in determining whether homeless persons with mental illness will obtain housing (1) and medical care (2) and live independent lives in the community (3). However, studies show that many mentally ill homeless persons fail to obtain benefits—or lose their benefits—because of difficulties in the application process or alienation from mainstream service providers (4,5,6,7). Persons with psychotic ideation, in particular, may be easily discouraged by the queues, paperwork, and protocols that characterize bureaucratic welfare systems (8).

The fact that homeless persons with mental illness do not always receive federal and state entitlements has been noted in intervention studies that have attempted to link these individuals with housing and treatment (9,10,11,12,13). Recent research has evaluated the effects of a streamlined application process, involving cooperation between the Social Security Administration and the Department of Veterans Affairs, on veterans' access to Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) (14). However, longitudinal studies of changes in these individuals' access to government entitlements over time are scarce, and the impact of welfare reform on income support in this population has received surprisingly little attention from researchers and policy makers (15).

In New York State and elsewhere, the welfare system is becoming increasingly restrictive. Substance abusers are not eligible for SSI or SSDI, public assistance must be earned through "workfare," and there are lifetime limits on assistance. In addition, monitoring of eligibility is increasing. Such monitoring may take the form of periodic recertification interviews or scheduled and unscheduled reviews of eligibility (personal communication, Timour K, 1999). The ambiguity and frustration associated with these new policies may render the application process even more daunting, and individuals who need assistance the most—homeless persons with mental illness—may be further barred from access to such assistance (16).

To examine the receipt of entitlements by homeless persons with psychotic ideation, we compared changes in receipt of Medicaid, SSI or SSDI, food stamps, and home relief (state welfare for single persons) by homeless persons with and without psychotic ideation between January 1997 and July 1998, a period during which significant changes in entitlement programs were implemented in New York State.

Methods

Sample and research design

A broader study, approved by the institutional review board of the National Development and Research Institutes, evaluated the efficacy of social work services provided by a mobile medical van to link primarily homeless persons who have substance use problems with government entitlements and substance abuse treatment. (Preliminary findings are available from the first author.) The van, operated by Project Renewal, parks in areas in which homeless persons congregate in New York City, such as soup kitchens, and provides free medical care. This mobile clinic was experimentally enhanced by the addition of a social worker who attempted to arrange entitlements and substance abuse treatment for eligible clients. In the broader study, among the 251 persons who were recruited, four-month follow-up data were available for 176 (70 percent). Here we present data for 159 of the clients who were followed up and who were defined as marginally or literally homeless and for whom measurements on key variables were obtained.

Measurement of variables

Participation in entitlement programs was measured at baseline and at follow-up by self-reported current receipt of Medicaid, SSI or SSDI, food stamps, and home relief. Reported monthly income from entitlements and the dollar value of food stamps were similarly assessed at both assessment points. If participants had lost benefits, they were asked to provide detailed descriptions of the perceived reasons for the loss.

Psychotic ideation was measured with a subscale of the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Instrument, designed to assess the classic symptoms of schizophrenia—paranoid ideation, formal thought disorder, delusions, and hallucinations (17). The version used in this study was modified to rule out intoxication and withdrawal, the effects of which often mimic the symptoms of psychosis (18). The clients reported the presence or absence of symptoms in the previous year during periods in which they were not using alcohol or drugs. The ten items, with response categories ranging from 0 to 4, were combined to form a total scale with a range of 0 to 40 (alpha=.87). Consistent with the definition used in a previous study (18), psychotic ideation was defined as a score of 0 to 10, and nonpsychotic was defined as a score of 11 to 40.

Additional measurements were obtained to determine whether the psychotic ideation was in fact independent of substance use and whether receipt of entitlements by persons with psychotic ideation was confounded by comorbid substance use, which could render clients ineligible for benefits. Dependence on drugs other than alcohol was measured with a screening scale designed to be consistent with the DSM-IV definition of dependence (19). Participants were deemed to be dependent if they endorsed at least three of nine items related to tolerance (needing increasing amounts of the drug to get high), dependence (not being able to cut down or quit), or abuse (using drugs despite a health problem or job loss) (alpha=.89).

A parallel set of items was used to assess dependence on alcohol specifically (alpha=.85). Given the questionable validity of self-reports of substance use in previous studies of high-risk populations (20), additional, biologically based measurements were obtained. The use of cocaine and opiates during the previous 30 days was assessed with radioimmunoassays of 1.3 cm of hair, measured from the scalp. In accordance with the laboratory protocols of Psychemedics Corporation, a positive result was defined as at least 5 ng of cocaine and at least 2 ng of opiate metabolites per 10 mg of hair.

Two dimensions of homelessness were also quantified—the number of months spent in the New York City shelter system and the number of months spent as "street homeless"—that is, spending nights in places such as parks—during the previous year.

Statistical procedures

The analysis was performed with SPSS-PC for Windows, version 6.1 (21). Changes in receipt of entitlements were reported as percentages of clients who gained or lost entitlements during a four-month period. A multivariate analysis (multiple linear or logistic regression) was used to examine associations between psychotic ideation and receipt of entitlements at follow-up, with receipt at baseline statistically controlled for.

Results

Sample

Most of the 159 study participants were male (116 clients, or 73 percent) and nonwhite; 116 clients (73 percent) were black, and 16 (10 percent) were Hispanic. Their mean±SD age was 40.3±7.9 years. Only four individuals had custody of their dependent children, and the median number of months of employment in the previous five years was 12. In conjunction with the experimental design of the broader study, 75 clients (47 percent) were assigned to receive assistance from a social worker in the medical van. Dependence on drugs other than alcohol was identified among 76 clients (48 percent), and dependence on alcohol specifically was identified among 43 clients (27 percent).

According to the hair assays, 122 clients (77 percent) had used cocaine and 29 clients (18 percent) had used opiates during the previous 30 days. The typical client had been "literally homeless"—that is, living on the streets—for 1.67 months during the previous year, with a mean of 2.41±1.67 months spent in the New York City shelter system. About a sixth (25 clients, or 16 percent) were identified as psychotic, which is similar to the estimate obtained in a previous study of homeless persons that used a similar method (18).

Comparisons between the 159 clients who were successfully followed up and the 83 clients who were not showed no significant differences at baseline in age, sex, ethnicity, custody of dependent children, the number of months of employment during the previous five years, the two dimensions of homelessness, the measurements of substance use, and the psychiatric measurements. Psychotic ideation was also not associated with any of these variables.

Changes in receipt of entitlements

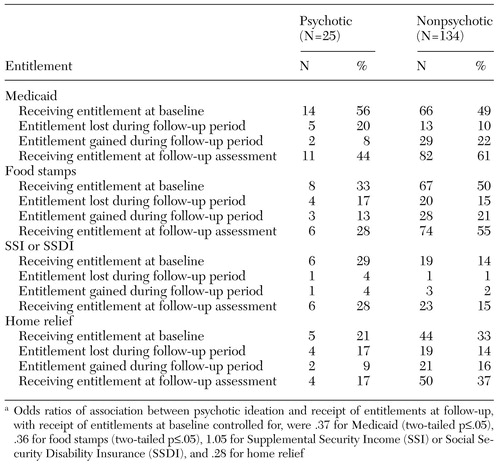

Receipt of entitlements at baseline and at follow-up by clients who did and clients who did not have psychotic ideation is summarized in Table 1. Also included are the proportions of clients in each group who were receiving entitlements at baseline but lost them during the follow-up period as well as those who were not receiving entitlements at baseline but who gained them during the follow-up period.

At baseline, the clients with psychotic ideation were more likely to be receiving Medicaid (56 percent compared with 49 percent of nonpsychotic clients) and SSI or SSDI (29 percent compared with 14 percent) but less likely to be receiving food stamps (33 percent compared with 50 percent) and home relief (21 percent compared with 33 percent).

About a fifth of the clients (35 clients, or 22 percent) lost one or more of the four entitlements during the follow-up period; 49 clients (31 percent) gained one or more of the four entitlements during the same period, which partially reflects the addition of a social worker to the mobile clinic. The clients with psychotic ideation were more likely to have lost Medicaid, food stamps, and home relief and less likely to have gained these entitlements. (Because of the multiple comparisons involved, tests of statistical significance were not conducted.) Reflecting this pattern of change, differences in receipt of entitlements at follow-up between clients who had psychotic ideation and those who did not, with receipt at baseline controlled for, were statistically significant for Medicaid and food stamps and were of borderline significance for home relief. Changes in receipt of SSI and SSDI were small in both groups.

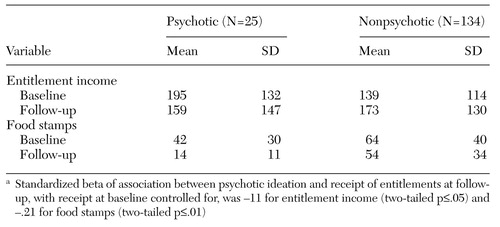

In a parallel analysis, the results of which are summarized in Table 2, we evaluated the mean levels of client-reported income or the monetary value of entitlements and food stamps at baseline and follow-up. There was a net increase in entitlement income between baseline and follow-up among the clients who did not have psychotic ideation (from $139 to $173), whereas the mean level of entitlement income among clients who had psychotic ideation declined from $195 to $159. The mean value of obtained food stamps decreased in both groups during the follow-up period, but the decline was greater among the clients who had psychotic ideation. Differences in the monetary value of entitlements and food stamps at follow-up between clients who had psychotic ideation and those who did not, with baseline values controlled for, were statistically significant.

Perceived reasons for loss of entitlements

According to the clients in this study, the principal reasons for loss of entitlements, if that occurred, were failure to show up for an eligibility review, a decree of ineligibility during an eligibility review, sanctioning due to noncompliance with the workfare requirements, and bureaucratic errors. The explanations for loss of benefits did not differ between clients who had psychotic ideation and those who did not.

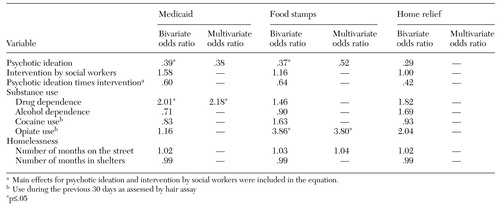

Changes in access to entitlements

Table 3 summarizes the effects of psychotic ideation, intervention by social workers, an interaction effect for psychotic ideation and intervention by social workers, substance use, and homelessness on the receipt of Medicaid, food stamps, and home relief at the follow-up assessment, with receipt at baseline controlled for. An interaction effect for psychotic ideation and intervention by social workers is also reported. Bivariate associations of psychotic ideation and drug dependence on receipt of Medicaid at follow-up were observed when receipt at baseline was entered into the equation. The effects of psychotic ideation and drug dependence on Medicaid at follow-up remained significant in a multivariate model when both variables as well as receipt of Medicaid at baseline were entered into the equation.

Bivariate associations of psychotic ideation and opiate use with receipt of food stamps at follow-up were observed when receipt at baseline was controlled for. In a logistic model that included both predictors, the effects of opiate use were statistically significant, whereas the effects of psychotic ideation were not. The nonsignificance of the association between psychotic ideation and receipt of food stamps in the multivariate model that included opiate use reflects a lack of statistical power rather than confounding, given the lack of a significant association between opiate use and psychotic ideation (r=.03). A borderline significant association of psychotic ideation and receipt of home relief at follow-up was found when receipt at baseline was controlled for, but no other bivariate associations were observed.

In an aggregate analysis of receipt of one or more entitlements during the follow-up period, the addition of a social worker was associated with receipt of entitlements at follow-up (odds ratio=2.44, p=.05). However, the effect of social work services on receipt of specific entitlements, considered separately, was not statistically significant. For either type of analysis—aggregate or specific—interaction effects for intervention group and psychotic ideation were not statistically significant, which suggests that social work services were neither more nor less effective among clients with psychotic ideation.

Discussion and conclusions

Even with the lack of statistical power resulting from the relatively small number of clients who had psychotic ideation and the short follow-up period, psychotic ideation was consistently associated with nonreceipt of Medicaid, food stamps, and home relief in this sample of homeless persons in New York City. Given the short follow-up period, the strength of these findings is striking. However, little change was observed in receipt of SSI or SSDI during the study period, and no differences were found between clients who had psychotic ideation and those who did not.

These findings cannot be dismissed as reflecting high levels of substance use among persons with psychotic ideation, which could have rendered these clients ineligible for SSI or SSDI and other programs, because no association was observed between psychotic ideation and four measures of substance use—self-reports of drug and alcohol dependence and biological assays of recent opiate and cocaine use.

The fact that data were collected during a period in which access to entitlements was increasingly restricted in New York State—January 1997 to July 1998—suggests that lack of access to entitlements among homeless persons with psychotic ideation may be exacerbated by these reforms. Welfare reform, which began with the disqualification of disability due to substance abuse as a primary reason for eligibility for SSI or SSDI and was followed by greater restrictions on eligibility for food stamps and state-level welfare programs as well as closer monitoring of eligibility for these programs, has been successful in that the welfare rolls have been reduced (15). However, in the process of "changing welfare as we know it," procedures must be implemented to ensure that the most needy individuals are not deterred from the application process.

A recent demonstration project to streamline applications for SSI and SSDI, which involved coordination by the Social Security Administration and the Department of Veterans Affairs, was found to be effective not only in reducing the application time but also in increasing the proportion of homeless persons with mental illness who were eligible for SSI or SSDI (14). In our study, SSI and SSDI were the only entitlements that were not associated with psychotic ideation status during a four-month period. Initiatives akin to the organizational linkage between the Social Security Administration and the Department of Veterans Affairs need to be implemented for Medicaid, food stamps, and home relief.

A broader, national research initiative, launched in 1994 by the Center for Mental Health Services of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, was designed to identify barriers to receipt of services and supports by homeless persons with mental illness. Project ACCESS (Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports) attempted to delineate factors associated with the receipt of services and assistance in this population (22). Initial results of that study, undertaken before much of the current welfare reforms occurred, found a statistically significant—although modest—association between diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and nonreceipt of services. Our findings suggest that, in the wake of welfare reform, psychotic ideation may be a significant barrier to receipt of services or assistance among homeless persons in New York City.

In evaluating the results and implications of this study, it should be noted that psychotic ideation was measured at baseline only—that is, change in psychotic ideation status was not assessed. Also, unmeasured variables may have confounded the association between psychotic ideation and receipt of entitlements, and reports of psychotic ideation may have been somewhat contaminated by environmental factors associated with homelessness, such as stress and poor nutrition (23).

Given the nonexperimental design of this study and the limitations we have noted, a causal effect of psychotic ideation on receipt of entitlements has not been clearly demonstrated. However, such an effect was strongly suggested by this longitudinal study of psychotic ideation and subsequent changes in receipt of entitlements during a four-month period. Homeless persons in New York City with serious symptoms, as reflected by psychotic ideation, may experience considerable difficulty in obtaining or keeping certain types of entitlements.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant 5-R01-DA-10431-03 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Dr. Nuttbrock, Dr. Rosenblum, and Dr. Magura are affiliated with the National Development and Research Institutes, 71 West 23rd Street, 14th Floor, New York, New York 10048 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. McQuistion is medical director of Project Renewal, Inc., and associate clinical professor of psychiatry at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

|

Table 1. Receipt of entitlements by homeless persons with and without psychotic ideation during a four-month follow-up perioda

a Odds ratios of association between psychotic ideation and receipt of entitlements at follow-up, with receipt of entitlements at baseline controlled for, were 37 for Medicaid (two-tailed p≤.05), .36 for food stamps (two-tailed p≤.05), 1.05 for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), and .28 for home relief

|

Table 2. Dollar values of entitlement income and food stamps received by homeless persons with and without psychotic ideation

|

Table 3. Effects of psychotic ideation and other variables on the receipt of selected entitlements at follow-up by homeless persons with and without psychotic ideation, with receipt of entitlements at baseline controlled for

1. Sosin MR, Grossman S: The mental health system and the etiology of homelessness: a comparison study. Journal of Community Psychology 19:337-350, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Padgett D, Struening E, Andrews H: Factors affecting the use of medical, mental health, alcohol, and drug treatment services by homeless adults. Medical Care 28:805-820, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lerman P: Deinstitutionalization and the Welfare State. New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 1984Google Scholar

4. Lamb HR, Bachrach LL, Kass F (eds): Treating the Homeless Mentally Ill. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1992Google Scholar

5. Calloway MO, Morrissey JP: Overcoming service barriers for homeless persons with serious psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services 49:1568-1572, 1998Link, Google Scholar

6. Klinkenberg DW, Calsyn RJ, Morse GA: The helping alliance for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 34:596-575, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Cohen N, Putman J, Sullivan A: The mentally ill homeless: isolation and adaptation. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:924-928, 1984Google Scholar

8. Kuhlman TL: Psychology on the Streets: Mental Health Practice with Homeless Persons. New York, Wiley, 1994Google Scholar

9. Calsyn RJ, Kohfeld C, Roades LA: Urban homeless people and welfare: who receives benefits? American Journal of Community Psychology 21:95-112, 1993Google Scholar

10. Lam JA, Rosenheck R: Street outreach to persons with serious mental illness: is it effective? Medical Care 37:894-907, 1999Google Scholar

11. First RJ, Rife JC, Kraus S: Case management with people who are homeless and mentally ill: preliminary findings from an NIMH demonstration project. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 14:87-91, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Lehman A, Dixon LB, Kernan E, et al: A randomized trial of assertive community treatment of homeless persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1038-1043, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Herman D, Opler L, Felix A, et al: A critical time intervention with mentally ill homeless men. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:135-140, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Rosenheck R, Frisman L, Kosprov W: Improving access to disability benefits among homeless persons with mental illness: an agency-specific approach to services integration. American Journal of Public Health 89:524-528, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Lehman J, Danziger S: Ending Welfare As We Know It: Values, Economics, and Politics. Cambridge, Mass, Electronic Policy Network. Available at http//epn/library/dang0l05.htmlGoogle Scholar

16. DeParle J: Success and frustration, as welfare changes. New York Times, Dec 30, 1997, p A1Google Scholar

17. Dohrenwend BP, Shrout P, Igri C, et al: Non-specific psychiatric distress and other dimensions of psychopathology in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:1229-1234, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Susser E, Struening EL: Diagnosis and screening for psychotic disorders in a study of the homeless. Schizophrenia 16:133-145, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Nuttbrock LA, Rahav M, Rivera JJ, et al: Outcomes of homeless mentally ill chemical abusers in community residences and a therapeutic community. Psychiatric Services 49:68-76, 1998Link, Google Scholar

20. Magura S, Kang SY: Validity of self-reported drug use in high-risk populations: a meta-analytical review. Substance Use and Misuse 31:1131-1153, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Nie N: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Chicago, SPSS Inc, 1990Google Scholar

22. Randolph FL: Improving systems through systems integration: the ACCESS program. American Rehabilitation 21:36-38, 1995Google Scholar

23. Lovell AM, Barrow SM, Struening EL: Between relevance and rigor: methodological issues in studying mental health and homelessness, in Homelessness: A Prevention-Oriented Approach. Edited by Jahiel RI. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992Google Scholar