Risk Factors for Psychosocial Dysfunction Among Enrollees in the State Children's Health Insurance Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors studied enrollees in the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) (Title XXI) to characterize risk factors for psychosocial dysfunction among children of the working poor. METHODS: Medical and psychosocial variables were included in a survey completed by 393 parents of children enrolled in SCHIP. Regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between these variables and scores on the Pediatric Symptom Checklist, a measure of psychosocial dysfunction among children. RESULTS: Stepwise multiple regression showed that parental dysphoria, parental history of psychiatric or substance use problems, childhood chronic medical illness, and exposure to traumatic events each contributed independently to variance in psychosocial dysfunction in this population, explaining 34 percent of total variance. CONCLUSIONS: Despite strong progress in implementing SCHIP at the state level, the behavioral health care needs of children of the working poor have not been well defined. This study identified risk factors that can be easily found in the patient's medical record or detected during an interview by the primary care physician. Thus screening to identify children at risk of psychosocial dysfunction is warranted among SCHIP enrollees.

Even though Medicaid eligibility rules have been eased, the number of children in the United States without health insurance had reached 10.5 million (14.2 percent) by 1994, representing the highest proportion of uninsured children since 1987 (1). To address this gap in health care coverage, Congress created the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) in 1997, allocating $48 billion over the next ten years to extend health care coverage to uninsured children. The SCHIP statute has enabled states to insure children who come from working families with incomes that are too high for them to qualify for Medicaid but too low to enable them to afford private health insurance. By July 1, 2000, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories had implemented SCHIP, covering nearly two million children.

Data on the behavioral health care needs of this vulnerable population have been limited but are important because of the link between economic conditions and mental health status. This link has been consistently documented in psychiatric epidemiology. Among adults, low family income, the defining characteristic of SCHIP enrollees, is associated more consistently with exposure to stressful life events than with either poor education or low occupational status (2). Persons of lower socioeconomic status are more strongly affected emotionally by most kinds of personal events. The same associations have been found among children (3,4,5).

Furthermore, pediatricians are less likely to identify psychopathology among children from single-parent and disadvantaged families than among other children (6). Data on the prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in the United States indicate that almost 21 percent have minimal impairment and 11 percent have significant impairment (7). The prevalence of mental disorders is even higher among disadvantaged children (8,9). The most common disorders are the disruptive disorders (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorders), mood disorders, and anxiety-related problems (10,11,12,13,14).

Behavioral outcomes during adolescence and young adulthood have been shown to be associated with biological and psychosocial risk factors that are exacerbated in disadvantaged families (15). For example, the mother's health during pregnancy, birth-related complications, and chronic medical illness during early childhood are related to future childhood behavioral problems (16,17).

Psychosocial dysfunction among children and adolescents has been associated with parental history of mood disorders and other psychiatric illnesses (18,19,20). Parental depression is a risk factor for the development of depression or other psychiatric disorders and general medical problems by young adulthood (21). Wickramaratne and Weissman (22) found that, compared with other children, children of parents with major depressive disorder had eight times the risk of childhood-onset major depressive disorder, three times the risk of anxiety disorder, five times the risk of conduct disorder, and five times the risk of early-adult-onset major depressive disorder (23).

Parental alcohol and drug use and abuse and lower socioeconomic status have been found to predict substance abuse and dependence among adolescents (5,24,25,26,27). Being exposed to traumatic events or losing a loved one during childhood (28,29) and witnessing violence have been associated with posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, externalizing behaviors, impairment in interpersonal and family relationships, and decline in academic performance (30).

Given the interaction between socioeconomic status and the above-mentioned risk factors for psychosocial distress, we hypothesized that medical history and exposure to traumatic events would independently contribute to psychosocial distress beyond the contribution of parental variables. Thus we sought to develop a model for identifying experience-based risk factors for psychosocial distress among children who were enrolled in SCHIP.

Methods

In the spring of 1998, University Behavioral Health (UBH) contracted with Jackson Memorial Hospital (JMH) Health Plan to provide carved out behavioral health services for children enrolled in SCHIP. JMH Health Plan is a health maintenance organization in Miami that delivers managed care to the medically underserved population. UBH is an academic managed behavioral health care organization in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the University of Miami School of Medicine. In the fall of 1999, a needs assessment process was initiated to identify the behavioral health care needs of children enrolled in SCHIP. All members of the Florida Healthy Kids population, all of whom are SCHIP enrollees, between the ages of five and 19 years who were continuously enrolled in the JMH Health Plan from April 1, 1999, through March 31, 2000 (N=12,153) were eligible to participate in the study.

A survey was mailed to a sample of families with children who were enrolled in SCHIP. A sample size that would provide an estimate within 5 percent of the population parameter at a 95 percent confidence level was obtained by using the formula N=(Py)(Pn)/SE2, where Py and Pn represent the proportion of respondents who answered yes or no, respectively, to a given question and SE is the standard error. A sample of 384 was calculated on the conservative assumption that there would be an even split in responses: (Py)(Pn)=.5×.5=.25, divided by the square of the standard error to produce a confidence interval of 95 percent (1.96).

A 20 percent response rate was estimated on the basis of previous surveys. Therefore, to obtain a statistically valid response, we multiplied the calculated sample size by five. Thus a random sample of 1,920 names and addresses was drawn from the health plan enrollment file, and surveys were mailed to the parent or parents of the SCHIP enrollees. All surveys mailed were in English. A cover letter written in English and in Spanish provided instructions for obtaining a Spanish version of the survey. A total of 402 surveys were returned, for a response rate of 21 percent. With nine surveys excluded from the sample because of missing data, we had 393 completed surveys.

Survey

The survey requested demographic information and information on other independent variables, including parental dysphoria, parental psychiatric and substance abuse history, maternal prenatal history and chronic childhood medical conditions, and exposure to traumatic events. Unweighted indexes were created by summing the yes responses to questions pertaining to the independent variables (31). Parental dysphoria was ascertained by asking "Have you been so sad, miserable, and depressed that it interfered with your daily life for the past two weeks?" Parental history of psychiatric and substance use problems was determined by summing the responses to the questions "Has the birth mother or father ever had a psychiatric problem?" and "Has the birth mother or father ever had a substance abuse problem?" All no responses were coded as 0, and yes responses were coded as 1.

The child's prenatal history was assessed with 12 categorical items, and chronic childhood medical conditions were assessed with six categorical items, respectively. Questions about prenatal history addressed maternal blood pressure, anemia, smoking status, and drug use during pregnancy. The childhood chronic medical conditions assessed were asthma, seizures, and diabetes. Prenatal and medical history was determined by summing the number of items endorsed in these two areas. Similarly, exposure to traumatic events was determined by summing the number of items endorsed from a list of eight items—for example, major community disaster, such as a hurricane; death of a parent; serious physical injury; and witnessing or experiencing severe violence.

The data for the study were originally collected as part of a quality improvement project at University Behavioral Health. Subsequently, a waiver of informed consent was requested from the institutional review board of the University of Miami and was granted.

Pediatric Symptom Checklist

An a priori hypothesis was that a child's psychosocial dysfunction would be related to parental dysphoria, parental psychiatric and substance abuse history, prenatal history and chronic childhood medical illness, and exposure to traumatic events. The dependent variable was the total score on the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC), a 35-item parent-report survey designed to detect psychosocial dysfunction among school-aged children (32). Parents rate the frequency of occurrences of 35 behaviors—for example, daydreams too much, fights with other children, or refuses to share; possible responses are never, sometimes, and often, scored 0, 1, and 2, respectively.

For children between the ages of six and 16 years, a PSC score above 28 has traditionally been considered positive—that is, indicating that the child should receive further assessment. However, recent research designed specifically to examine the utility of the PSC among persons of low socioeconomic status has shown that a cutoff score of 24 best approximates the desired balance between sensitivity and specificity (8). Use of the traditional cutoff score of 28, established across populations with various income levels, resulted in a false-negative rate of 35 percent. PSC scores were shown to have acceptable validity and reliability among inner-city children (33) and in a low-income Hispanic community similar to the population of Miami-Dade County (34).

Furthermore, the parental PSC response rate is constant across sociodemographic subgroups (35). To further examine the relationship between an indicated positive screen for psychosocial dysfunction and parents' perception of their child's mental health, the parents were asked whether they thought their child had emotional problems.

Analyses

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to explore the relationship between categorical variables and total score on the PSC. Pearson correlations were used for interval data (age). Stepwise multiple regression was used to determine whether medical history or exposure to traumatic events made a contribution to psychosocial distress beyond that explained by parental dysphoria and parental psychiatric or substance abuse history.

SPSS's regression and frequencies procedures were used to evaluate the model's assumptions. Responses to items on the PSC were slightly skewed in the positive direction because of higher frequencies in the negative tail resulting from an absence of the behavior addressed in the survey question. Several transformations were applied to these variables without a marked improvement in skewness or normality, resulting in no transformations.

Results

The children in the sample ranged in age from five to 19 years. Their mean± SD age was 11.9±3.4 years. Pearson product-moment correlation showed no significant relationship between age and PSC score. One-way ANOVA showed that sex, race or ethnicity, and primary language spoken in the home were also unrelated to PSC score. A total of 213 children (54 percent) were boys, and 180 (46 percent) were girls. A total of 259 children (66 percent) were identified by a parent as Hispanic, 79 (20 percent) as African American, 28 (7 percent) as non-Hispanic Caucasian, and 27 (7 percent) as Haitian or other. The race or ethnicity of the parent was essentially the same as that of the child. The primary language spoken in the home was Spanish (192 parents, or 49 percent), followed by English (179 parents, or 46 percent), Creole (13 parents, or 3.5 percent), and other (9 parents, or 1.5 percent), which is consistent with the demographic pattern of Miami-Dade County. The number of years the children had spent in school ranged from zero to 13; the median school grade was sixth grade. Most of the children (383, or 98 percent) were full-time students. Thirty-one children (8 percent) had repeated a grade.

On average, the families had two children living in the home, and generally the mother was the primary caretaker (287 parents, or 73 percent). Most primary caretakers worked outside the home (350, or 89 percent); of these, most had full-time day jobs (310, or 79 percent). All but one parent had a telephone. Fifty-nine parents (15 percent) indicated that they did not have transportation for health care appointments, and 141 (36 percent) said that no child care was available for when they were away from home. The incomes of the families ranged between the poverty level and twice the poverty level.

Twenty-seven (7 percent) of the birth mothers or fathers had a history of psychiatric illness, and 44 (11 percent) had a history of substance abuse. Forty-seven (12 percent) of the parents who completed the survey had experienced dysphoria, and 21 (5 percent) indicated that they currently felt depressed; of these, three (14 percent) had received medication for their depression. Parents who reported a psychiatric history were 2.5 times as likely to have taken their child for outpatient treatment as those who indicated no psychiatric history.

We examined the relationship between parents' perception of their child's emotional problems and the child's total score on the PSC. Sixty parents (15 percent) indicated that their child had an emotional problem. Correspondingly, 57 children (15 percent) had PSC scores of 24 or more, indicating dysfunction. In contrast, when the traditional cutoff score of 28 was used, 41 children (10 percent) had PSC scores indicative of dysfunction. The correlation (r) between parental assessment of emotional problems and a total score of 24 or more on the PSC was .438 (p<.001).

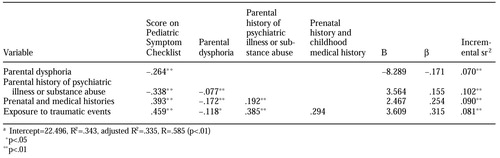

We used stepwise multiple regression to determine whether medical history or exposure to traumatic events explained psychosocial distress beyond parental variables (parental dysphoria and parental psychiatric or substance abuse history). Table 1 lists the correlations between the variables, the unstandardized regression coefficients (B) and intercept, the standardized regression coefficients (Β), the semipartial correlations (sr2), and R, R2, and adjusted R2 after all four independent variables had been entered. Variables were entered in the order in which they appear in the table. R was significantly different from zero at the end of each step. After step 4, when all the independent variables had been entered, R was .585 (F=50.45, df=4, 392, p<.01).

After step 1, with parental dysphoria in the equation, R2 was .070 (F= 29.32, df=1, 391, p<.01). After step 2, with parental history of psychiatric or substance use problems added, R2 was .172 (F=40.38, df=2, 390, p<.01). After step 3, with prenatal history and childhood chronic medical history included, R2 was .262 (F=45.87, df=3, 289, p<.01). After step 4, with childhood exposure to traumatic events included in the equation, R2 was .343 and adjusted R2 was .335 (F=50.49, df=4, 288, p<.01). Thus all the independent variables contributed independently to the explained variance of psychosocial dysfunction. Specifically, medical history and exposure to traumatic events explained variance beyond the contribution of parental variables.

Discussion

The State Children's Health Insurance Program was designed to provide physical and behavioral health care insurance for children whose family incomes are too high for them to qualify for Medicaid but too low for them to be able to afford private insurance. The mental health care needs and psychosocial risk factors of SCHIP enrollees are not known. Risk factors for psychosocial distress are often amplified in disadvantaged populations because of the attendant stressors of poverty. In this study we examined the contribution of medical history and exposure to traumatic events, beyond the contribution of parental variables, to psychosocial dysfunction.

Current parental dysphoria, parental history of psychiatric or substance use problems, childhood chronic illness, and childhood exposure to traumatic events each independently contributed to psychosocial dysfunction. Furthermore, medical history and trauma contributed to the explained variance beyond the contribution of parental variables. No significant differences in psychosocial dysfunction were found by age, sex, race or ethnicity, or language spoken in the home.

Fourteen percent of the children whose parents were surveyed had PSC scores of 24 or more, the cutoff for dysfunction. When the traditional cutoff of 28 was used, 9 percent of the children had scores indicating dysfunction. These rates compare with 22 percent in an inner-city pediatric outpatient sample (33), 15 to 27 percent in an outpatient sample of children of low socioeconomic status, and 9 percent in an outpatient sample of children of high socioeconomic status (35), all based on a cutoff score of 28.

Thus the rate reported here is somewhat lower than rates previously reported for children from low-income families. However, 89 percent of the primary caregivers in our study were employed in either part-time or full-time work, which suggests that they had a high level of functionality. Furthermore, because we used a sample selected from the total SCHIP population rather than a clinical sample from pediatric offices, it is not surprising that the PSC scores in the SCHIP population were lower.

Because the study design was cross-sectional, no causal associations can be made between risk factor variables and psychosocial dysfunction. However, there is mounting evidence implicating poverty, medical history, and trauma as mediating variables in the development of psychosocial dysfunction among children (17,29,36,37). Children of parents who have an affective disorder have a greater risk of developing a psychiatric disorder than children whose parents do not. Life-table estimates indicate that a person whose parent has an affective disorder has a 40 percent likelihood of experiencing an episode of major depression by the age of 20 years and is more likely to exhibit general difficulties in functioning (13).

Another factor contributing to psychosocial dysfunction in this population is the relationship between socioeconomic status and access to behavioral health care. The 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey, a national probability sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population, showed that children with poor mental health who came from low-income families were less than a third as likely to have a mental health-related visit than children of similar mental health status who came from high-income families (38). Our study showed that 15 percent of families enrolled in SCHIP did not have transportation to health care appointments, which limited their access to care.

We used unweighted ordinal-composite variables as the independent variables in this study. This approach did not take into consideration the relative weight of an event. For example, does experiencing a hurricane compare to losing a parent? We sought to identify experience-related risk factors for psychosocial dysfunction that could potentially be used in a clinical setting. Clinimetric composite measures—as opposed to psychometric measures—are typically unweighted to provide clinicians with brief and uncomplicated ratings for identifying risk (37). Although researchers might seek to identify an index of the relative weights of individual events, the clinical utility of such an index might be compromised.

Because the surveys mailed were in English, with Spanish translations available on request, there was a bias toward English speakers. A further limitation of the study was that the data came from a regional sample. We do not know whether these findings are generalizable to a national sample. However, to the extent that other communities are similar to the South Florida SCHIP population, which is composed largely of African-American or Hispanic children living in a densely populated urban area in households with incomes less than twice the poverty level specified in federal guidelines, these data may prove useful.

This study was a first step toward the development of a multiregion project designed to carefully study the behavioral health care needs of children of the working poor. It would be wrong to presume that this population of children has the same needs as children from more affluent families and that behavioral health programs for their care should be the same.

Conclusions

Information about the presence of conditions such as parental dysphoria and a history of mental illness, childhood chronic illness, and childhood exposure to traumatic events should be readily available in primary care medical records and managed care service use records. Early identification of at-risk children would reduce costs throughout the medical sector (39,40) and reduce health care costs by decreasing the use of psychiatric outpatient and inpatient services (41). The results of this study support the use of screening in these settings, the development of preventive intervention strategies for children whose parents have received diagnoses of a mood or substance use disorder, and comprehensive mental health services for the parents.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the University of Miami School of Medicine (M861), 1150 N.W. 14th Street, Suite 501, Miami, Florida 33136 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Results of stepwise multiple regression of parental dysphoria, parental history of psychiatric problems or substance abuse, prenatal history and childhood medical history, and childhood exposure to traumatic events on psychosocial dysfunction for a sample of 393 families with children enrolled in the State Children's Health Insurance Programa

a Intercept=22496, R2=.343, adjusted R2=.335, R=.585 (p<.01)

1. Health insurance for children: many remain uninsured despite Medicaid expansion. Washington, DC, US General Accounting Office, 1995Google Scholar

2. McLeod J, Kessler R: Socioeconomic status differences in vulnerability to undesirable life events. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 31:162-172, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. McLeod J, Shanahan MJ: Trajectories of poverty and children's mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 37:207-220, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wade TJ, Pevalin DJ, Brannigan A: The clustering of severe behavioural, health, and educational deficits in Canadian children: preliminary evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth. Canadian Journal of Public Health 90:253-259, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Reinherz H, Giaconia R, Hauf A, et al: General and specific childhood risk factors for depression and drug disorders by early adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:223-231, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Jellinek M, Little M, Murphy J, et al: The Pediatric Symptom Checklist: support for a role in a managed care environment. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 149:740-746, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, et al: The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, accessibility, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study: Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:865-877, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Simonian S, Tarnowski K: Utility of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist for behavioral screening in disadvantaged children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development 31:269-278, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Silverman WK, Ollendick TH (eds): Social Class in Developmental Issues in the Clinical Treatment of Children. Needham Heights, Mass, Allyn & Bacon, 1999Google Scholar

10. Knitzer J: Mental health services to children and adolescents: a national view of public policies. American Psychologist 39:905-911, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Guarnaccia PJ, Lopez S: The mental health and adjustment of immigrant and refugee children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 7:537-553, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Brand AE, Brinich PM: Behavior problems and mental health contacts in adopted, foster, and nonadopted children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 40:1221-1229, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TR: Children of affectively ill parents: a review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:1134-1141, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Samaan RA: The influences of race, ethnicity, and poverty on the mental health of children. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 11:100-110, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Raine A, Brennan P, Mednick B, et al: High rates of violence, crime, academic problems, and behavioral problems in males with both early neuromotor deficits and unstable family environments. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:544-549, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Uljas H, Rautava P, Helenius H, et al: Behavior of Finnish 3-year old children: I. effects of sociodemographic factors, mother's health, and pregnancy outcome. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 41:412-419, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Angel RJ, Angel JL: Physical comorbidity and medical care use in children with emotional problems. Public Health Reports 111:140-145, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hay DF, Zahn-Waxler C, Cummings EM, et al: Young children's views about conflict with peers: a comparison of the daughters and sons of depressed and well women. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 33:669-683, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Zahn-Waxler C, Iannotti RJ, Cummings EM, et al: Antecedents of problem behaviors in children of depressed mothers. Development and Psychopathology 2:271-291, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Frankel K, Wambolt MZ: Chronic childhood illness and maternal mental health: why should we care? Journal of Asthma 35:621-630, 1998Google Scholar

21. Kramer R, Warner V, Olfson M, et al: General medical problems among the offspring of depressed parents: a 10-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:602-611, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Wickramaratne PJ, Weissman MM: Onset of psychopathology in offspring by developmental phase and parental depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:933-942, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Weissman M, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, et al: Offspring of depressed parents:10 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:932-940, 1997Google Scholar

24. Chassin L, Pitts S, DeLucia C, et al: A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 108:106-119, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Briggs-Gowan M, Horwitz S, Schwab-Stone M, et al: Mental health in pediatric settings: distribution of disorders and factors related to service use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:841-849, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Lyons R, Wolfe R, Lyubchik A: Depression and parenting of young children: making the case for early preventive mental health services. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 8:148-153, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Shiner R, Marmorstein N: Family environments of adolescents with lifetime depression: associations with maternal depression history. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:1152-1160, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Hammen C: Self-cognitions, stressful events, and the prediction of depression in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 16:347-360, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Shaw JA: Children, adolescents, and trauma. Psychiatric Quarterly 71:227-243, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Warner B, Weist M: Urban youth as witnesses to violence: beginning assessment and treatment efforts. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 25:361-377, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Wright J, Feinstein A: A comparative contrast of clinimetric and psychometric methods for constructing indexes and rating scales. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 45:1201-1218, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Murphy JM, Jellinek M, Milinsky S: The Pediatric Symptom Checklist: validation in the real world of middle school. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 14:629-639, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Murphy JM, Reede J, Jellinek MS, et al: Screening for psychosocial dysfunction in inner-city children: further validation of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:1105-1111, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Murphy J, Ichinose C, Hicks R, et al: Utility of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist as a psychosocial screen to meet the federal Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) standards: a pilot study. Journal of Pediatrics 129:864-869, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Little M, et al: Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist to screen for psychosocial problems in pediatric primary care: a national feasibility study. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 153:254-260, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Shaw JA, Applegate B, Schorr C: Twenty-one-month follow-up study of school-age children exposed to Hurricane Andrew. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:359-364, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:626-632, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Cunningham PJ, Freiman MP: Determinants of ambulatory mental health services use for school-age children and adolescents. Health Services Research 31:409-427, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

39. Tweed DL, Goering P, Lin E, et al: Psychiatric morbidity and physician visits: lessons from Ontario. Medical Care 36:573-585, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: Long-term patterns of service use and cost among patients with both psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. Medical Care 36:835-843, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Tomiak M, Berthelot JM, Mustard CA: A profile of health care utilization of the disabled population in Manitoba. Medical Care 36:1383-1397, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar