Psychodynamic Psychotherapy and Clomipramine in the Treatment of Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors compared a combination of clomipramine and psychodynamic psychotherapy with clomipramine alone in a randomized controlled trial among patients with major depression. METHODS: Seventy-four patients between the ages of 20 and 65 years who were assigned to ten weeks of acute outpatient treatment for major depression were studied. Bipolar disorder, psychotic symptoms, severe substance dependence, organic disorder, past intolerance to clomipramine, and mental retardation were exclusion criteria. RESULTS: Marked improvement was noted in both treatment groups. Combined treatment was associated with less treatment failure and better work adjustment at ten weeks and with better global functioning and lower hospitalization rates at discharge. A cost savings of $2,311 per patient in the combined treatment group, associated with lower rates of hospitalization and fewer lost work days, exceeded the expenditures related to providing psychotherapy. CONCLUSIONS: Provision of supplemental psychodynamic psychotherapy to patients with major depression who are receiving antidepressant medication is cost-effective.

Better integration of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication is a significant challenge in the treatment of mental illness (1,2), and new studies should aim to demonstrate that the provision of supplemental psychotherapy improves outcomes of patients with depression for whom effective medication is prescribed (3,4,5,6,7). Previous studies have shown that combined treatment is superior to antidepressant medication alone in selected subgroups of inpatients who have depression (8), especially those with more severe symptoms (9).

Our basic hypothesis was that combined treatment is more beneficial than antidepressant medication alone among psychiatric patients with major depression who are referred to general psychiatric services. Such patients have a slow or partial response to standard psychiatric treatment (1,10) and may benefit from simple psychotherapeutic programs designed to facilitate an alliance with a therapist (11) and to work out the psychosocial factors that are common correlates of poor response to antidepressant medication (12,13). Preliminary investigations have indicated that simple psychodynamic psychotherapy in the context of general psychiatric services is feasible when delivered by skilled, well-trained nurses under close supervision (14,15). Better psychodynamic psychotherapeutic processes predict better long-term outcomes for patients who have depression (15). Finally, an outpatient crisis intervention that combined intensive care, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and antidepressant medication was associated with lower treatment costs than usual psychiatric treatment (16).

To further investigate the cost-effectiveness of combined treatment for major depression, we compared a combination of antidepressant medication and psychodynamic psychotherapy with antidepressant medication alone in a randomized controlled trial.

Methods

Subjects and randomization

Between 1994 and 1996, a psychiatrist and a research nurse screened consecutive patients who were referred for acute outpatient treatment at a community mental health center. A total of 390 patients between the ages of 20 and 65 years with a new episode of care and symptoms of depression were selected by four independent psychologists. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of a major depressive episode on the basis of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), whatever the severity of any concurrent suicidal ideation, personality psychopathology, or past resistance to treatment, and a score of at least 20 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). (Possible scores on the HDRS range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating more severe depression.) Exclusion criteria were bipolar disorder, psychotic symptoms, severe substance dependence, organic disorder, mental retardation, history of severe intolerance to clomipramine, and poor command of the French language.

The ethics committee of the department of psychiatry at the University of Geneva approved the study. Informed written consent was obtained from each patient before assignment to treatment.

A total of 110 patients were eligible for the study. Ten of these were diverted to another study, and five dropped out before randomization. The remaining 95 patients were randomly assigned to one of the two outpatient treatment groups on an intent-to-treat basis—47 to the combined treatment (experimental) group and 48 to the clomipramine (control) group. The random assignment process included stratification by presence of personality disorders, past major depressive syndrome, and gender.

Twenty-one patients (12 in the experimental group and nine in the control group, or 22 percent) were excluded from the analyses—four who did not return for treatment (three in the experimental group and one in the control group), three who dropped out against medical advice (two in the experimental group and one in the control group), and 14 who were discharged because they had exclusion characteristics that were not detected at entry, including severe alcohol or drug dependence (five in each group) and adverse effects (two in each group). These patients were not significantly different from the other patients in terms of the main outcome variables at intake. The 74 patients who completed the study were not significantly different from the 21 who were withdrawn or from the group of 95 as a whole.

Treatment

We compared two ten-week acute treatment programs for major depression: clomipramine combined with psychodynamic psychotherapy and clomipramine alone. Both treatments involved the same clomipramine protocol and intensive nursing in a specialized milieu. In addition, the amount of structured psychodynamic psychotherapy provided during combined treatment was comparable to the amount of supportive care provided during treatment with clomipramine alone. Supportive care involved individual sessions aimed at providing empathic listening, guidance, support, and facilitation of an alliance by one carefully designated caregiver.

To ensure reliable standards of treatment, distinct nursing teams were trained for six months in the use of specific manuals. The attendant psychiatrist and the chief nurse agreed on the following guidelines for referring a study patient to inpatient care: a change to a manic episode, suicidal threats or severe lack of control and disruption to the alliance or to interpersonal bonds, severe inhibition preventing attendance at the center, a serious threat to caregivers and significant others, and a confused state. A careful review indicated that all guidelines were followed.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy. Preliminary reports on patients treated with psychodynamic psychotherapy have focused on the relationships between the alliance process and outcome (14), indicating that both nonspecific and specific ingredients of psychotherapy contribute to successful crisis intervention among patients with depression (15). It has been observed that a "treatment barrier" associated with personality psychopathology produces traumatic experiences and acute interpersonal conflicts in patient-caregiver relationships (16). The inactivation of such a barrier predicts alliance, treatment response, and outcome (14).

Thus for this study we made several assumptions. First, we assumed that alliance is an intersubjective process that depends on personality traits and management of resistance, impasse, and rupture (17). Second, we assumed that these obstacles to the alliance are activated by acute narcissistic discomfort that stems from various combinations of current traumatic experiences and enduring conflicts between the idealized expectations of the infant and the realistic needs of the adult. Third, we assumed that the treatment barrier prevents an adequate response to antidepressant treatment by standing in the way of a positive self-image and reinvestment in rewarding interpersonal relationships (14). Finally, we assumed that, when framed as a mourning process, psychodynamic psychotherapy and its supervision may break the vicious cycle between narcissistic discomfort and the reinforcement of pathological personality traits, thus inactivating the treatment barrier and its negative effect on the remission process.

Designated effective ingredients of psychodynamic therapy are a structure for the therapeutic relationship, empathy and emotional expression, insight, awareness, and facilitation and reinforcement of new interpersonal bonds. The corresponding appropriate interventions for obtaining these ingredients are emphasis of the value of therapeutic relationships and their evolution; facilitation of affect catharsis through empathic listening to the unique personal experience of the patient and active designation (expression in verbal terms) of the overwhelming feelings underlying his or her distress; recollection of present and past life crises that offer insight into enduring patterns of maladaptive interpersonal relationships and psychological conflicts facilitating bond disruption; focus on compulsive idealization of the corresponding attachment styles, beloved objects, and grandiose self-images and on the active ignorance of the unpleasantness of such processes; and breaking away from excessive concern about separation, deception, and loss to reinforce better self-caring, help seeking, and new investments. The corresponding treatment stages are nonspecific alliance process and psychoeducation, working alliance, insight, focusing, awareness, mourning, and reality reinvestment.

Four nurses were selected on the basis of their proven clinical experience (more than five years) with patients with depression, their crisis intervention practice under psychodynamic supervision (more than two years), and their demonstrated psychotherapeutic skills with patients with depression.

The nurses who worked with the patients who received combined treatment had weekly supervisory sessions with a psychoanalyst. These sessions covered setting limits and maintaining an alliance, developing empathy, developing insight and awareness, clarifying patients' internal conflicts, and facilitating the separation process at the termination of treatment. According to psychoanalytic works that stress that unconscious conflicts are barely understandable in a psychiatric situation, the primary aim was to work out the "treatment barrier-like" reactions that undermined active cooperation and rational management of psychiatric treatment (18). Nevertheless, the corresponding transference-countertransference relationships were investigated when they posed a major threat to continuation of treatment.

Clomipramine protocol. Clomipramine was administered at a dosage of 25 mg on the first day, gradually increasing to 125 mg on the fifth day. Electrocardiograms were performed before the start of the protocol and were repeated during weeks 1 and 2. Drug monitoring was conducted during weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8 and at discharge. Clinicians were allowed to adjust the dosage of clomipramine on the basis of the patient's clinical status and achievement of an optimal plasma concentration of clomipramine plus desmethylclomipramine (between 200 and 300 ng/L). Previous studies have demonstrated a strong treatment response with this dosing strategy (19). Alternative treatment consisting of 20 to 40 mg of citalopram a day was permitted for patients who refused the clomipramine treatment or experienced severe side effects.

Instruments and assessment

At intake and at ten weeks, three psychologists assessed the severity of depression with the SCID, the HDRS, and a Health-Sickness Rating Scale (HSRS) (15). In addition, three experienced psychiatrists administered the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) at intake and at discharge. The number of days of hospitalization and sick leave were recorded by independent psychologists. The intraclass correlation coefficients were .79 for the HDRS, .76 for the GAS, and .93 for assessment of major depressive episode. The HSRS scores were rated by consensus.

All raters were independent. The nurse therapists and the members of the clinical staff did not participate in the outcome assessments. The psychologists who made the assessments of hospitalizations, number of days of hospitalization, number of days of sick leave, and GAS scores were blinded to each patient's treatment assignment. Blinding is difficult to maintain in the case of patients receiving intensive care in a general psychiatry service, so the individuals who rated the presence and severity of major depression and HSRS score at ten weeks were not blinded to treatment assignment.

Adherence to therapy was monitored by two psychologists through weekly one-hour sessions during which several treatment fidelity indexes were rated by consensus, including the adequacy of the treatment format, the treatment technique, and the process levels attained—nonspecific alliance, working alliance, insight, focusing, awareness, mourning, and reality reinvestment (20). In this article, only adequacy of treatment is reported.

Clomipramine dosage schedules and plasma clomipramine concentrations were recorded on a compliance form. Unit costs were computed for each item of the treatment program. Expected expenditures (in U.S. dollars) for ten weeks of treatment were $2,012 for combined treatment and $1,270 for clomipramine alone, for an average daily cost of $29 and $18, respectively. We assumed that expenses for clinical supervision, clomipramine administration, laboratory services, equipment, and assets would be the same for both treatment groups. The indirect costs of loss of work days were computed on the basis of an average unit cost of $156 a day, which was developed by the economics and public health section of the Geneva Bureau of Statistics.

Data analysis

Point comparisons of the treatment groups were performed according to the metric characteristics of an a priori hierarchy of seven major outcome variables: hospitalization, number of days of hospitalization, whether the patient was in full remission (score of seven or less on the HDRS), treatment failure (persistence of a major depressive episode), severity of depression (based on HDRS scores), GAS score, and score on the "adjustment to work" subscale of the modified HSRS. Possible scores on this subscale range from 1 to 5, with lower scores indicating better adjustment. Changes over time were examined with repeated-measures analyses of variance, with type of treatment as a grouping factor. Analyses of covariance and two-way analyses of variance were used to control for age, gender, past major depressive syndrome, and global functioning at intake on the observed relationships between treatment choice and the main outcome variables. To control for intent to treat, the analyses were repeated with all 95 patients who had been randomly assigned to treatment.

Results

Patient characteristics

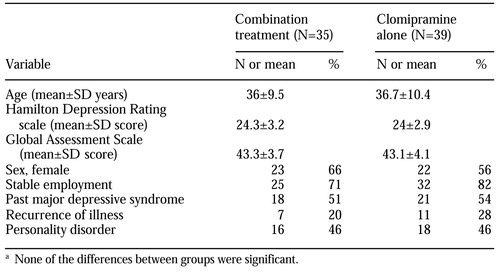

The basic demographic and clinical characteristics at intake for the 74 patients who were included in the analyses are summarized in Table 1. The patients in both treatment groups were predominantly young women with moderate to severe depression and poor global functioning. There were no significant differences in characteristics between the two groups at intake.

Treatment characteristics

The mean±SD duration of treatment tended to be shorter for the patients who received combined treatment (82.3±20 days, median=77, range, 49 to 138) than for those who received clomipramine alone (90.5±19.3 days, median=85, range, 61 to 160). No significant differences between groups were found in the number of days of clomipramine treatment at ten weeks (57.6±14.8 days in the combined treatment group and 56±15.1 days in the clomipramine group), the number of days of clomipramine treatment at discharge (67.8±23.8 and 72.4±24.3, respectively), or the number of switches to citalopram (five and six, respectively). Both treatment groups had low dropout rates (two patients, or 6 percent, in the combined treatment group and one patient, or 3 percent, in the clomipramine group), fair compliance (plasma drug concentrations of 225.4±104.3 and 225.7±135.6 ng/L, respectively), and an adequate treatment format (33 patients, or 94 percent, and 38 patients, or 97 percent, respectively).

Outcome

Outcome at ten weeks. The repeated-measures analysis of variance showed a marked negative effect of time on mean±SD HDRS scores at ten weeks (8.9±7 in the combined treatment group and 9.7±7.3 in the clomipramine group; F=286.4, df=1, 72, p<.001). No treatment effect was noted. However, the patients who received combined treatment were less likely to experience treatment failure (major depressive episode present at ten weeks): three patients (9 percent) compared with 11 patients (28 percent) (Fisher's exact test, p=.04) and had better scores on the adjustment to work subscale (1.7±.8 compared with 2.1±.8; Mann-Whitney U=864, df=1, p=.04).

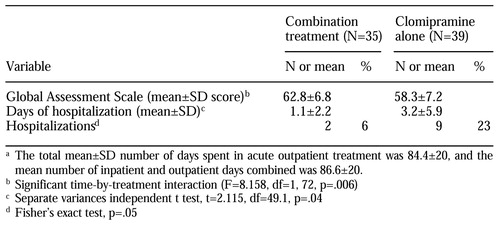

Outcome at discharge.Table 2 lists mean GAS scores, mean number of hospitalizations and days, and number of hospitalizations for the two groups. Repeated-measures analysis of variance showed a significant treatment-by-time interaction for GAS scores. Post hoc tests showed a significant group effect at discharge (F=7.87, df=1, 72, p=.006) but not at intake. In addition, assignment to combined treatment was associated with a lower rate of hospitalization and fewer days of hospitalization. The patients in this group lost fewer work days during treatment (46.1±37.1 days compared with 57.9±38.6 days); the difference was significant when we controlled for whether the patient was employed at intake (34.5±23 days compared with 56.2±34.6 days; t= 2.44, df=38.0, p=.02).

This finding was unchanged when we repeated the analyses and controlled for age, gender, initial severity of depression, GAS score at intake, compliance, and intent to treat. Among patients who had optimal plasma clomipramine concentrations (250 to 400 ng/L), the benefits of combined treatment were superior to those of antidepressant medication alone.

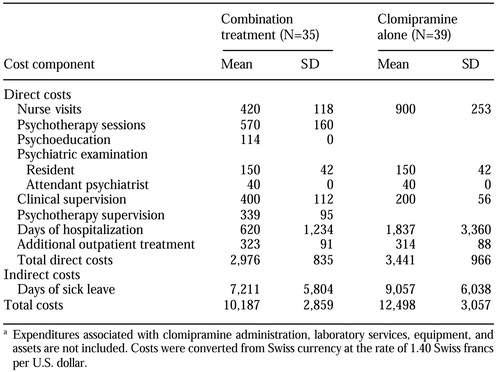

Costs

The costs associated with treating the two groups of patients are listed in Table 3. Combined treatment was associated with a mean savings of $465 per patient. In addition, the sick leave costs were lower for the patients who received combined treatment than for those who received clomipramine alone, with a mean savings of $1,846 per patient. Assignment to combined treatment was associated with an overall savings—including direct and indirect costs—of $2,311 for the ten-week period. Among patients who had stable employment when they entered the study, the savings were markedly higher at $3,394 in indirect costs.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that supplemental psychotherapy improves the cost-effectiveness of acute outpatient treatment for patients with major depression who are receiving effective medication. Combined treatment demonstrated significant advantages in terms of both functional outcome and service use. These findings may depend on characteristics of the treatment groups. For example, community-service patients who have more interpersonal conflicts and personality psychopathology (3,9) may have a higher rate of treatment failure when pharmacotherapy is used alone. Because persistent work impairment is not unusual after significant improvement of depressive symptoms (21), these data suggest that psychotherapy enhances the response to antidepressant medications in an outcome dimension that is of major concern in mental health (22).

This study had both strengths and limitations. Its strengths included its hypothesis-testing design, the fact that there was an effective control condition, and the use of well-balanced treatment groups, careful drug monitoring, and quality control of treatment provision. However, several assessment issues deserve more discussion. A caveat should be made concerning the higher rate of treatment failure among patients who did not receive psychodynamic psychotherapy, because the assessment of major depression at ten weeks was conducted without blinding the raters to patients' treatment assignment. However, patients who were in full remission at ten weeks had lower GAS scores, a lower rate of hospitalization, and fewer work days lost at discharge; all of these variables were assessed by raters blinded to treatment assignment.

Another limitation is related to the quality of the treatment provided. Because the therapists were not certified psychotherapists and transference interpretation was not a central concern, "psychodynamic psychotherapy" may not be an appropriate term for the intervention used in this study. Nevertheless, the primary aim went far beyond treatment optimization and psychoeducation (23). According to Luborsky's model (24), the therapeutic relationship focused on a specific conflictual theme—treatment barrier—but the critical accomplishment was narcissistic impasse working out through the mourning process rather than neurotic conflict working through. Given the considerable emphasis in psychodynamic psychotherapy on processing abnormal personality traits, exploratory psychotherapies (25,26) provide a closer model of the technique used in this study.

Together with the results of other studies (27), the data from our study contrast with previous reports that psychodynamic psychotherapy has little efficacy among psychiatric patients (28). One possible explanation for these differences is that ours was a simple intervention provided by professional, well-trained caregivers and not an independent treatment administered by external psychotherapists. In addition, the psychodynamic psychotherapy we used had both psychodynamic and nonpsychodynamic components. Further analyses of the data would clarify which of these factors better explains the results.

Conclusions

This study showed that antidepressant medication combined with psychodynamic psychotherapy is superior to antidepressant medication alone in the treatment of outpatients with major depression, which suggests that psychodynamic psychotherapy may be a factor in the cost-effectiveness of acute treatment of major depression.

Acknowledgment

This project was partly supported by grant 32-33829 from the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research.

Dr. Burnand, Dr. Andreoli, and Dr. Kolatte are affiliated with the University of Geneva Psychiatric Center, 24 rue Micheli-du-Crest, 1211 Geneva 14, Switzerland (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Venturini is with Centre Médico-Pédagogique in Geneva. Dr. Rosset is with Belle-Idée Hospital System in Geneva.

|

Table 1. Characteristics at intake of 74 patients with major depression who were assigned to treatment with a combination of psychodynamic psychotherapy and clomipramine or with clomipramine alonea

a None of the differences between groups were significant

|

Table 2. Outcome measures at discharge among 74 patients with major depression who were assigned to treatment with a combination of psychodynamic psychotherapy and clomipramine or with clomipramine alonea

a The total mean±SD number of days spent in acute outpatient treatment was 844±20, and themean number of inpatient and outpatient days combined was 86.6±20.

|

Table 3. Mean per-patient costs associated with the treatment of patients with major depression who were assigned to treatment with a combination of psychodynamic psychotherapy and clomipramine or with clomipramine alone, in US. dollarsa

a Expenditures associated with clomipramine administration, laboratory services, equipment, and assets are not included. Costs were converted from Swiss currency at the rate of 1.40 Swiss francs per U.S. dollar.

1. Clarkin JF, Pilkonis PA, Magruder KM: Psychotherapy of depression: implications for reform of the health care system. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:717-723, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lazar SG, Gabbard GO: The cost effectiveness of psychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 6:307-314, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

3. Thase ME: Integrating psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for treatment of major depressive disorder: current status and future considerations. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 6:300-306, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

4. Manning DW, Frances AJ: Combined therapy for depression: critical review of the literature, in Combined Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy for Depression. Edited by Manning DW, Frances AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

5. Wexler BE, Cicchetti DV: The outpatient treatment of depression: implications of outcome research for clinical practice. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:277-286, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Scott J: Psychological treatments for depression: an update. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:289-292, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Conte HR, Plutchik R, Wild KV, et al: Combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for depression: a systematic analysis of the evidence. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:471-479, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Bowers W: Treatment of depressed inpatients: cognitive therapy plus relaxation plus medication and medication alone. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:73-78, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Thase ME, Greenhouse JB, Frank E, et al: Treatment of major depression with psychotherapy or psychotherapy-pharmacotherapy combinations. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1009-1015, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, et al: Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression: a five-year prospective follow-up of 431 subjects. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:809-816, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Siegel LR: Alliance not compliance: a philosophy of outpatient care. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56(suppl 1):11-16, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

12. Shea MT, Widiger TA, Klein MH: Comorbidity of personality disorders and depression: implications for treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:857-868, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Michels R: Psychotherapeutic approaches to the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58(suppl 13):30-32, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

14. Andreoli A: What we have learned about emergency psychiatry and the acute treatment of mental disorders, in Emergency Psychiatry in a Changing World. Edited by De Clercq M, Andreoli A, Lamarre S, et al. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1999Google Scholar

15. Andreoli A, Frances A, Gex-Fabry M, et al: Crisis intervention in depressed patients with and without DSM-III-R personality disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:732-737, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rosset N, Andreoli A: Crisis intervention and affective disorders: a comparative cost-effectiveness study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 30:231-235, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

17. Safran JD, Muran JC: Negotiating the Therapeutic Alliance: A Relational Treatment Guide. New York, Guilford, 2000Google Scholar

18. Diatkine R, Quartier F, Andreoli A: Psychose et changement. Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1991Google Scholar

19. Balant-Gorgia AE, Gex-Fabry M, Balant LP: Clinical pharmacokinetics of clomipramine. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 20:447-462, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Dazord A, Gérin P, Andreoli A, et al: Pretreatment and process measures in crisis intervention as predictors of outcome. Psychotherapy Research 1:135-147, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Mintz J, Mintz LI, Arruda MJ, et al: Treatments of depression and the functional capacity to work. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:761-768, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Murray CJL, Lopez AD: The Global Burden of Disease: World Health Organization. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

23. Shuchter SR, Downs N, Zisook S: Biologically informed psychotherapy for depression. New York, Guilford, 1996Google Scholar

24. Luborsky L: Principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy: a manual for supportive-expressive treatment. New York, Basic, 1984Google Scholar

25. Knight RP: An evaluation of psychotherapeutic techniques. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 16:113-124, 1952Medline, Google Scholar

26. Waldinger RJ, Gunderson JG: Effective psychotherapy with borderline patients. New York, McMillan, 1987Google Scholar

27. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1563-1569, 1999Link, Google Scholar

28. Crits-Christoph P: The efficacy of brief dynamic psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:151-158, 1992Link, Google Scholar