Rehab Rounds: Teaching Persons With Severe Mental Disabilities to Be Their Own Case Managers

Personal Effectiveness for Successful Living (1), a flexible and highly individualized form of social skills training, has been continuously offered for more than 30 years in community mental health centers, outpatient clinics, private practices, state hospitals, and veterans' medical centers throughout the world (2). Because this type of training uses basic principles of human learning that apply to everyone—such as goal setting, modeling, behavioral rehearsal or role playing, repeated practice, positive reinforcement for small changes, and community-based assignments—persons with every type of disorder who come for psychiatric services can be involved (3).

Building on the motto of the National Association of Social Workers, "helping people help themselves," social skills training aims more specifically to teach people to help themselves. Skills training enables clients to learn how to get their own needs met with less involvement of case managers and other clinicians.

Procedures used in the module

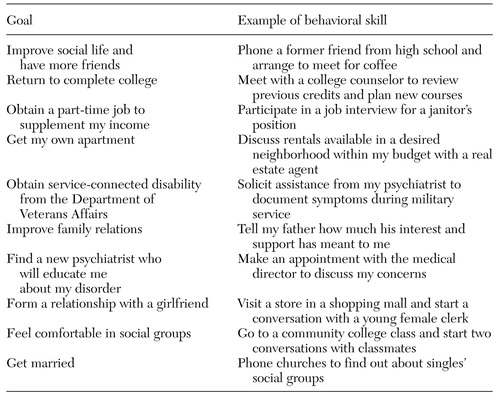

The Personal Effectiveness for Successful Living module, which can be conducted in individual, family, or group formats, begins with the clinician's assisting clients to articulate their personal long-term goals. This is the most technically challenging part of the training, because many individuals will get stuck focusing on their symptoms or problems and pose their goals in negative terms, such as "I'd like to be free of my depression," "I'd like to be able to leave the hospital," "I don't have enough money to enjoy life," or "I don't want to be so lonely." The clinician must help the client translate these problems into positive goals by asking questions such as, "What would you like to be able to do/like to do/enjoy doing if you were free of your depression or voices?"; "What can you do to convince your doctor that you are ready to leave the hospital?"; "How might you reduce your expenses or earn some money?"; and "Do you know anyone with whom you could meet and do things together?" Some personal goals of consecutive clients who have participated in this type of skills training, framed in positive and constructive terms, are listed in Table 1. When skills training is conducted in a group, the members' personal goals are listed on a flip chart or marker board to maintain focus and overcome attentional deficits.

The next step is to help the individual identify a specific interpersonal action that, if accomplished, would bring that individual closer to his or her personal goal. Thus a series of stepwise, incremental goals leading to the personal goal of "having more friends" might begin with "attend a Bible class where there would be others who share my interest in religion," "sign up for tennis instruction at the local recreation district," "join the Sierra Club and go on its weekly hikes with other members," "call a friend from high school with whom I've stayed in contact and invite him to join me for coffee or a movie," "ask my case manager whether she knows of anyone on her caseload whom I might enjoy getting to know," or "ask one of the members of my psychosocial club if I could join her for dinner at her table." Examples of concrete and short-term goals selected as targets for training in skills groups, linked to clients' various long-term personal goals, are also listed in Table 1.

The acronym SMART (specific, meaningful, attainable, realistic, and transfer) can be used to recall the attributes of setting highly specific and incremental goals for the skills training. First, goals for training are specific: they are described by answering the questions "What is the goal?"; "With whom do I need to interact to achieve the goal?"; and "When and where will this interaction likely take place?" Second, the goals are meaningfully linked to a longer-term personal goal. Third, each goal should be attainable—neither too difficult nor too easy to accomplish in real life. Fourth, the goal should be realistic so as to be consistent with the individual's rights and responsibilities and to improve the individual's social functioning, while building on the individual's strengths, deficits, and resources. Finally, community-based case managers and natural supporters should be mobilized to promote the transfer of the skills practiced in the group into the clients' everyday life.

The procedures used for this type of flexible and individualized skills training have been described in treatment manuals (1,3,4). The procedure usually takes no more than five or ten minutes per person, which makes group training with up to ten clients cost-effective. The principles used in training are based on procedural, active, and implicit learning that can compensate for many of the cognitive deficits experienced by people with schizophrenia and other mental disabilities. Thus benefits from skills training sidestep the neurocognitive obstacles posed by verbal learning, insight, and memory that characterize traditional "talk" therapies and discussion groups.

Once the specific goal for the skills training session is chosen and endorsed by client and clinician, a modeling interaction is provided by the clinician or, in the case of group sessions, by a peer who has the appropriate skills and experience. The modeling sequence is closely annotated, and the individual is asked to repeat the verbal and nonverbal elements of communication that were demonstrated by the model; for example, the eye contact, intonation of voice, facial expression, posture, gestures, phrases, and speech used to initiate and respond in the interaction. If the person is unable to identify the discrete skills that have been demonstrated by the model, this sequence may have to be repeated or made less complex.

Next, the individual has an opportunity to practice the verbal and nonverbal elements of the skill that were demonstrated by the model. However, the clinician stays close to the person while he or she goes through the role play and provides coaching and feedback to increase the adequacy of the performance. Immediate positive feedback is given to the person for whatever was done well. In a group setting, the leader structures and elicits positive feedback by asking each of the group members what he or she liked about how the leader communicated in each scene. Posters on the walls or on easels remind participants of the specific verbal and nonverbal communication and problem-solving skills that are the subjects for the training. Video feedback is often given, with special care taken to highlight the segments of the role play that showed positive communication skill. If it appears that the individual would benefit from further practice, additional rehearsing, either within the skills training session or outside of it, can be prescribed.

The "rubber hits the road" with homework or community assignments. Each person in training is given a reminder card with the date, assignment, and prompts to make good eye contact, speak with an appropriate tone of voice, use facial expression to convey emotions, and communicate with the goal in mind. Sessions should be at least weekly, but progress in achieving community-based, personal goals can be accelerated through the use of more frequent sessions.

Results of skills training

A vast body of literature on social skills training with persons who have schizophrenia and other major mental disorders, as well as practice guidelines, documents that a wide range of social and independent living skills can be learned, that the skills are durable, and that they generalize into home, work, and community settings (5). But what about clinical applications of social skills training by practitioners in ordinary facilities outside of academic research studies? Do individuals who go through the training actually complete their assignments in the community and reach their personal goals? Given the individualized nature of treatment goals, this question may provide a more valid test of skills training than do standardized assessment tools that tap general areas of social and community functioning but that may not be particularly relevant to the rehabilitation service plan for an individual.

A review of 79 clients who consecutively joined Personal Effectiveness for Successful Living groups led by nurses, trainees in psychiatry and psychology, occupational therapists, and psychiatric technicians was conducted in five community mental health centers and two outpatient clinics. The cohort of 79 clients identified a total of 123 personal goals with 658 specific behavioral assignments, of which 72 percent were satisfactorily attained. These same individuals reported successful achievement of 63 percent of their overall personal goals. The rate of goal attainment varied, of course, from client to client. Generally, individuals with greater thought disorder and deficit-type negative symptoms did more poorly, and individuals whose symptoms were stable or in remission did best. Persons who had long-term personal goals that were highly motivating—for example, restoring a driver's license or keeping child custody—also tended to do best, with rates of assignment completion of about 90 percent. Because the clinician's evaluation and response to self-reported completion of assignments are nonjudgmental, the clients' descriptions of their assignments are highly reliable compared with direct observation of assignment completion (6).

Conclusions

Few outcomes are more valued by consumers than achieving their own personalized goals. This is the primary aim of social skills training. What better way to empower a mentally disabled person than to equip that person with the know-how and skills to meet his or her own needs without direct assistance from a clinician? Skills training operationalizes the ancient Chinese aphorism, "Give a man a fish and he has a meal; teach a man to fish and he can feed himself for life." The title "Personal Effectiveness for Successful Living" was chosen for the training module because it conveyed empowerment to clients and motivated them to participate in the gradual, effortful learning enterprise.

The further evolution, development, and dissemination of skills training methods will come from clinical services research and a broader focus on goals that are identified by consumers themselves. Controlled studies of skills training combined with supported employment are under way to determine whether teaching fundamental workplace skills can improve employment tenure among persons with serious and persistent mental illness. Because so many persons with mental disabilities are sexually active and at risk of unwanted pregnancy, rape, and sexually transmitted disease, a new Friendship and Intimacy module has been produced (7). Computer-aided and errorless training are technical innovations aimed at enhancing individual-paced and efficient learning of skills.

Afterword: For many evidence-based psychosocial treatments that require programmatic overhaul and new human resources, organizational and administrative obstacles and lack of commitment from top and middle management may torpedo the effort. On the other hand, social skills training can be readily implemented by a single clinician even when others in the organization are not interested in this modality. We have noted the successful application of skills training when a psychologist decided to lead groups in an acute inpatient unit, an occupational therapist began a group in a partial hospital program, and a nurse developed a group for geropsychiatry outpatients.

The importance of acquiring social skills is underscored by a substantial body of research that has shown high correlations between social skills and community and social functioning, even after symptoms and cognitive impairment have been controlled for (8). The growing use of social skills training in the mental health marketplace should reduce the burden and stress on case managers in intensive case management programs and should enable clients to steer their daily lives more autonomously (9). The zeitgeist for this type of learning-based empowerment is favorable, as reflected by a new self-advocacy curriculum developed by the National Mental Health Consumers' Self-Help Clearinghouse, the National Mental Health Association, and the National Association of Protection and Advocacy Systems.

Dr. Liberman is affiliated with the psychiatric rehabilitation program at the department of psychiatry of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Dr. Kopelowicz, also affiliated with UCLA, is medical director of the San Fernando Mental Health Center, a program of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health. Both Dr. Liberman and Dr. Kopelowicz are editors of this column. Send correspondence to Dr. Liberman at UCLA Psychiatric Rehab Program, 300 UCLA Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, California 90095 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Personal goals selected by clients participating in the social skills training module Personal Effectiveness for Successful Living

1. Liberman RP, King LW, DeRisi WJ, et al: Personal Effectiveness: Teaching People to Assert Their Feelings and Improve Their Social Skills. Champaign, Ill, Research Press, 1975Google Scholar

2. Liberman RP: International perspectives on skills training for the mentally disabled: special issue. International Review of Psychiatry 10:1-89, 1998Google Scholar

3. Liberman RP, DeRisi WJ, Mueser KT: Social Skills Training for Psychiatric Patients. Boston, Allyn & Bacon, 1989Google Scholar

4. Bellack AS, Mueser KT, Gingerich S, et al: Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

5. Heinssen RK, Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A: Psychosocial skills training for schizophrenia: lessons from the laboratory. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:21-46, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. King LW, Liberman RP, Roberts J, et al: Personal effectiveness: a structured therapy for improving social and emotional skills. European Journal of Behavioural Analysis and Modification 2:82-91, 1977Google Scholar

7. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consultants: Friendship and Intimacy Module. Camarillo, Calif, Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consultants, 2002Google Scholar

8. Mueser KT, Bellack AS: Social skills and social functioning, in Handbook of Social Functioning in Schizophrenia. Edited by Mueser KT, Tarrier N. Boston, Allyn & Bacon, 1998Google Scholar

9. McGrew JH, Wilson RG, Bond GR: An exploratory study of what clients like least about assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services 53:761-763, 2002Link, Google Scholar