Severity of Children's Psychopathology and Impairment and Its Relationship to Treatment Setting

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study investigated the settings in which children and adolescents were treated to determine whether clinicians assigned individuals who had greater needs to more intensive treatment. METHODS: Subjects were 603 children four to 16 years of age who visited a mental health treatment facility in Western Australia, where, as is the case throughout Australia, universal publicly funded health care is provided. DSM-IV criteria were used to make diagnoses, and clinicians assessed each child's level of impairment. The clinicians assigned the children to inpatient treatment, day treatment, or outpatient treatment, or they saw the child only for a psychiatric consultation. Measures included parents' and children's reports of children's psychopathology and parents' reports of family functioning, family life events, and parental mental health symptoms and treatment. RESULTS: Clinicians' ratings of impairment were highest for children assigned to the inpatient and day treatment settings. Parents' ratings of total psychopathology and of internalizing and externalizing symptoms were highest for children in the inpatient and day treatment settings. Parents' reports also indicated that family dysfunction and parental alcohol problems were most severe in the inpatient group. No differences in parents' mental health problems were found across treatment settings. CONCLUSIONS: Children with more severe psychopathology and more severe family dysfunction and parental problems were more likely to be provided treatment in the most costly and time-intensive treatment settings. The results provide empirical evidence for what many clinicians consider best clinical practice—to assign children and families to treatment settings appropriate to their level of impairment.

To justify their expense, specialty psychiatric services must demonstrate that they are worth the cost (1,2,3,4,5), which implies that there should be a direct relationship between the severity of a patient's diagnosis and level of impairment and the intensity and expense of the treatment. A similar direct relationship should exist between the treatment setting and the success of the therapeutic outcome. Thus, to justify the expense of 24-hour-a-day care, an inpatient psychiatric hospital setting would be expected to treat patients who have the most severe diagnoses or those with multiple diagnoses and the greatest degree of functional impairment and to provide better treatment outcomes for such severely disturbed patients than would be provided in less costly and less restrictive settings.

Previous studies have found that parents' ratings of psychopathology are significantly higher for child and adolescent inpatients than for outpatients (6). Parents of children who were inpatients or in day treatment rated their children as having a more severe disorder and as being more anxious and aggressive than did parents of outpatients (7). Therrien and Fischer (8) studied a sample of 28 children matched by age, ethnicity, and psychiatric diagnosis and found that ratings by parents indicated that inpatients were significantly more disturbed than outpatients because of the greater frequency of problematic behaviors among inpatients.

Several studies have involved larger samples. One study of 199 adolescent patients and their families found that inpatients and their parents had significantly higher mean scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) scales than did outpatients and their parents (9). Further, combined MMPI scale data for each mother and adolescent pair accurately predicted the treatment setting of about 75 percent of the adolescents (9).

Pfeffer and colleagues (10) studied 308 preadolescents and found differences in psychiatric diagnoses among inpatient, outpatient, and nonpatient groups. Conduct disorder was the most common diagnosis among inpatients and adjustment disorder among outpatients. The prevalence of borderline personality disorder was higher among inpatients than among outpatients or nonpatients, as were rates of past and recent general psychopathology, suicidal behavior, aggression, antisocial behavior, loss of consciousness, and assaultive behavior. Children who were treated in different settings also differed in family and demographic characteristics. Rates of parental separation were significantly higher among inpatients than outpatients and among outpatients than nonpatients. Inpatients were also more likely to have mothers who displayed suicidal behavior.

This study investigated whether patients and their families were treated in an appropriate treatment setting. We were particularly interested in whether patients with the most severe symptoms and the greatest degree of impairment received the most intensive treatment. Australia provides universal publicly funded health care. Thus an underlying assumption was that in a management environment in which cost implications are not paramount, clinicians would provide more intensive treatments to individuals with the greatest need. We hypothesized that clinicians would identify the greatest need among patients who had two or more areas of psychopathology or impairment—for example, children who experienced a broad range of psychopathology or who had comorbid axis I and axis II disorders, or children who, in addition to their own psychopathology, had parents with psychopathology or who came from a dysfunctional family. An important aspect of this study is that it investigated treatment provided in a generalist, nonuniversity environment. In addition, a wide range of evaluation instruments were used to assess treatment need. Data included parents' and children's reports of the children's psychopathology and competency, clinicians' ratings of the children's functional impairment and identification of comorbid axis I and II diagnoses, and parents' reports of family dysfunction and parental psychopathology.

Methods

Sample

The sample was drawn from all children referred consecutively to a government-funded, nonuniversity child and adolescent mental health facility in Perth, Australia, between 1996 and 1998. This facility, the psychological medicine clinical care unit, was located in the only pediatric hospital in Western Australia and provided a range of assessment and treatment options. Written informed consent to use these data was obtained from parents, and approval for the project was obtained from the hospital's scientific advisory and ethics committees.

During the study period, 672 children and their families visited the psychological medicine clinical care unit. Usable data were obtained for 603 children, or 77 percent. Of these, 328 (54.4 percent) were male, and 275 (45.6 percent) were female. The children ranged in age from four to 18 years, and their mean±SD age was 10.39±3.95 years. The mean age of males was significantly lower than that of females (9.29±3.72 years, compared with 11.59±3.88 years; t=6.78, df= 502, p<.001). Nearly half of the children (300, or 49.7 percent) had Australian-born parents. A total of 144 children (23.9 percent) had parents who were immigrants, and 159 children (26.3 percent) had one Australian-born parent and one immigrant parent. Only 26 children (4.3 percent) had an Aboriginal father, and the same number (26, or 4.3 percent) had an Aboriginal mother. English was the main language spoken in most homes (581 homes, or 96.3 percent).

A total of 266 fathers (44.1 percent) and 230 mothers (38.2 percent) had some college education or were qualified in one of the trades. Few had not attended secondary school (26 fathers, or 4.3 percent, and 18 mothers, or 3 percent). The parents of the children in the sample were underemployed compared with Australian norms. A total of 129 fathers (21.4 percent) and 355 mothers (58.9 percent) reported that they were currently unemployed. Self-reported rates of emotional disorders were also higher among the parents than in the Australian general population. Ninety-three fathers (15.5 percent) and 180 mothers (29.9 percent) stated that they had received treatment for emotional problems. Seventy-one fathers (11.8 percent) and 75 mothers (12.4 percent) stated that they had been hospitalized for a mental health complaint.

Procedures

Children and adolescents may gain access to the range of care provided by the psychological medicine clinical care unit via two different entry points. Emergency cases are triaged by pediatric medical and nursing staff from the accident and emergency unit. The on-call pediatric psychiatry registrar assesses the patient and recommends inpatient admission or referral to a mental health day treatment or outpatient program. More commonly, entry occurs after a multidisciplinary intake meeting at which staff discuss the patient's written referral and assign the patient to the treatment setting deemed most appropriate. Care options include admission to an eight-bed short-stay inpatient unit, where the average length of stay is 8.5 days; enrollment in one of two specialized day treatment programs; and enrollment in outpatient care provided by a mental health practitioner, such as a child and adolescent psychiatrist, a clinical psychologist, a social worker, or a pediatric mental health nurse. The day treatment programs consist of a child and adolescent eating disorders team and a day hospital that serves primarily children who have externalizing problems. A fourth option is assessment for the purposes of tertiary consultation only.

Measures

Data collection is incorporated into the assessment protocol of all individuals and their families, regardless of the entry point. Information about family background is collected, as is demographic information about the referred individual and both biological parents, such as age, sex, ethnicity, parents' educational level, medical and psychiatric history, and recent life events. Mental health symptoms recently experienced by the parents are assessed with the General Health Questionnaire, a widely used 12-question self-report instrument for screening for mental illness (11,12). The Family Assessment Device General Functioning Scale (FAD-GFS), a 12-item questionnaire completed by the principal caregiver (13), assesses family functioning and has psychometric properties adequate for research use (14).

Patients' emotional and behavioral problems are assessed by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (15), which is completed by the principal caregiver, and the Youth Self-Report (YSR) (16). The CBCL is a 120-item parent-report instrument. The primary caregiver reports the child's emotional and behavioral symptoms and areas of social, family, and school competence. The YSR, which complements the CBCL, is completed by youths aged 11 to 17 years. A total of 359 patients in the sample were in this age range; of these, 226 (63 percent) completed the YSR. Adolescents with early-onset psychosis were excluded. One hundred males (44.4 percent) completed the YSR, compared with 116 females (55.6 percent).

Both the CBCL and the YSR provide T score measures of total psychopathology, internalizing symptoms (anxiety and depression), and externalizing symptoms (aggression and delinquency). (T scores represent conversion of raw scores to scores derived from a normative sample of nonreferred peers.) Possible T scores on the three subscales range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater psychopathology. Each of the instruments also measures competency in the domains of school, other activities, and social interactions; the total competency score is the average of the three domain scores. Possible scores on the three domains range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater competency. Both the CBCL and the YSR have been used extensively in child and adolescent mental health research and have suitable psychometric properties (17). Both have been used with Australian youths (18).

Clinicians—including child and adolescent psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and child psychiatry and psychology registrars—assigned each patient a level of impairment on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF) (19) and provided a psychiatric diagnosis. To ensure interrater reliability, all clinicians used the DSM-IV diagnostic guidelines and formulated DSM-IV diagnoses.

Statistical analysis

Treatment setting was analyzed as an ordinal variable and sex as a categorical variable. Age and the total and subscale scores on the CBCL and the YSR, the competency scores, the FAD-GFS scores, the General Health Questionnaire scores, and the life event total scores were treated as continuous variables. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) or chi square analysis was used as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at the .05 probability level. SPSS for Windows, version 8, was used to manipulate and analyze data.

Results

Treatment settings

Five possible outcomes from the initial intake meeting were identified. The largest group of children in the sample (250, or 41.5 percent) received treatment in an outpatient setting. Others were admitted as inpatients (126 children, or 20.9 percent) or were enrolled in a day treatment program (68 children, or 11.2 percent). A total of 130 children (21.5 percent) were seen for a consultation only. For a small group (eight children, or 1.3 percent), treatment was not deemed necessary, and data for this group were excluded from further analysis.

Investigation of the possible confounding effects of sex indicated that girls were more likely to be treated as inpatients and boys were more likely to be treated in the day treatment program or seen for consultation only (χ2=18.78, df=3, p<.001). Children admitted as inpatients or to the day treatment program were also significantly older than children seen as outpatients or seen for consultation only (mean±SD ages of 12.18±3.15, 11.73±2.33, 10.38±3.89, and 9.47±4.09 years, respectively; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Scheffé tests, F=14.17, df=3,703, p<.001). Parental educational levels were used as proxy measures of socioeconomic status. Chi square analyses indicated that the mothers' and fathers' educational levels did not differ significantly between treatment settings.

Parents' reports

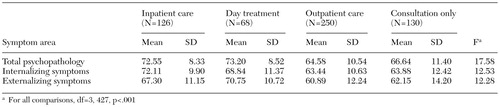

Table 1 presents mean CBCL scores for mental health symptoms calculated from the reports of parents of children in the four treatment settings. An ANOVA with post hoc Scheffé tests showed significant differences across the four treatment settings in the total psychopathology score, the internalizing symptoms score, and the externalizing symptoms score. The mean total psychopathology scores of children in the inpatient setting and the day treatment program were significantly higher than those of children in outpatient treatment and in the consultation-only group. Inpatients also had significantly higher internalizing scores than outpatients and than children in the consultation-only group. The internalizing scores of children in day treatment were significantly higher than those of children in outpatient care. This pattern was repeated across settings for the externalizing symptoms scores. Children in inpatient and day treatment had significantly higher externalizing scores than children in outpatient care, and children in day treatment had significantly higher externalizing scores than children in the consultation-only group.

Scores above 60 on both the internalizing and externalizing scale were considered to be high. Chi square analysis showed that children with high scores were more likely to be assigned to the inpatient or day treatment settings than to outpatient care (χ2=10.55, df=3, p<.05).

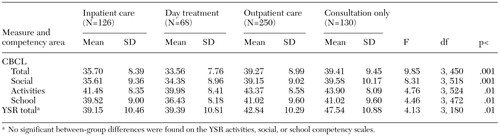

Parents' reports of children's competencies are summarized in Table 2. One-way ANOVA with post hoc Scheffé tests indicated that the total competency scores of the inpatient and day treatment groups were significantly lower than those of the outpatient and consultation-only groups. Outpatients had the highest scores in social competency, and children in day treatment had the lowest scores in activities and school competency.

The relationships between treatment setting and family variables were investigated. The variables included were FAD-GFS scores, parents' self-reports of their psychological history, current mental health symptoms of the parents as measured by the General Health Questionnaire, and parents' self-reports about their use of alcohol. FAD-GFS scores were compared across settings with use of ANOVA with post hoc Scheffé tests. The only significant finding was for scores on the FAD-GFS, which measures family functioning. Scores for the inpatient group were significantly higher than scores for the consultation-only group (mean±SD scores of 25.46±6.14 and 22.38±5.82; F=4.80, df=3,485, p<.005).

Chi square analysis did not reveal any significant differences across treatment settings in the mothers' or fathers' self-reports of emotional problems. Significant differences in parents' scores on the General Health Questionnaire were found across settings (F=7.97, df=3,504, p<.001). Parents whose children were inpatients had significantly higher scores than parents whose children were in the day treatment program, in outpatient treatment, or in the consultation-only group (mean±SD scores of 4.94±3.83, 3.08±3.78, 2.87±3.42, and 2.71±3.42, respectively). Higher scores on the General Health Questionnaire indicate more severe psychiatric symptoms. Alcohol consumption was found to be more of a problem in the homes of children who were inpatients than in the homes of children who were treated in other settings (F=2.96, df=3,639, p<.05).

Adolescents' self-reports

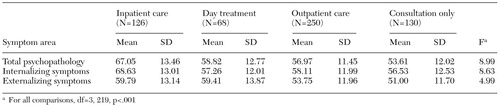

The YSR was completed by youths 11 to 17 years of age. Table 3 presents the mean YSR scores, which were similar to the CBCL scores. One-way ANOVA with post hoc Scheffé tests revealed significant differences in total psychopathology scores across treatment settings. Adolescents in the inpatient unit were significantly more likely to report psychopathology than those in the day treatment program or the consultation-only group. The internalizing scores of inpatients were significantly higher than those of day treatment patients, outpatients, and patients seen for assessment only. The externalizing scores of both inpatients and day treatment patients were significantly higher than those of patients in the consultation-only group, but they were not significantly different from those of outpatients. The total competency scores of the adolescent inpatients and the adolescents in day treatment were significantly lower than those of outpatients and patients in the consultation-only group. No significant differences were found between settings in the scores of adolescents in the other areas of competency.

Clinicians' reports

Chi square analysis was used to determine whether axis II diagnoses differed significantly across treatment settings. Inpatients were more likely than outpatients and patients in the consultation-only group to have an axis II diagnosis. Day treatment patients were also more likely to have an axis II diagnosis than patients in the consultation-only group. Clinicians' ratings indicated that patients in all the groups had some degree of impairment. Ratings for patients in the inpatient and day treatment groups were significantly higher than ratings for outpatients and those in the consultation-only group (F=17.90, df= 3,602, p<.001).

Discussion

We hypothesized that patients would receive more intensive treatment if they experienced both internalizing and externalizing symptoms, had significant psychosocial impairment, or had comorbid axis II conditions. We also hypothesized that children with more severe family problems, such as being part of a dysfunctional family or having parents with past or current mental health problems, problematic use of alcohol, or clinically significant levels of psychological distress, would receive more intensive treatment.

Inpatients and day treatment patients had the highest total psychopathology scores and the greatest degree of clinician-rated impairment; inpatients were significantly more impaired than outpatients and than children in the consultation-only group. Inpatients and day treatment patients were more likely than children in the other settings to have high scores on both the CBCL internalizing and externalizing subscales, and inpatients were more likely than all the other children to have a comorbid axis II diagnosis. These results provide full or partial support for the "double-jeopardy" hypothesis.

The proportions of parents with a history of mental health problems were similar across the four treatment settings. However, parents of inpatients were more likely than parents of children in the other settings to report current mental health symptoms and problems with alcohol use. Children in the inpatient group experienced more family dysfunction than those in the other three groups. It should be noted that although parents of inpatients were more likely to have current mental health symptoms and problems with alcohol use, the research design did not permit conclusions about the direction of the association or the issue of causation.

Our findings in this generalist setting are consistent with findings of several studies conducted in university-affiliated clinics. In those studies, children who were inpatients and those who were in day treatment exhibited more psychopathology (7), and the behavior of inpatients was more problematic than that of outpatients (8). It has been argued that diagnosis alone is not a sufficient indicator of the need for treatment (20). Rather, having problems in several domains is the most common reason for treatment seeking among children and adolescents (21). Our results indicate that the greater an individual's impairment in multiple domains, the more likely it is that he or she will receive care in a more costly and restrictive treatment setting. Our findings require replication and further study. However, the study provided some empirical validation for what most clinicians would agree is best clinical practice.

From an economic perspective, our findings suggest that funding is appropriately spent on individuals and families with the greatest need, at least in the settings we studied. Although it seems logical that children and families with greater psychopathology would have access to more treatment resources, this relationship is only one of several complex interconnections, and further research is needed to investigate the relative efficacy of treatment modalities across a variety of outcomes.

The study had some limitations. Measures of cognitive impairment, language skills, socioeconomic status, and comorbid medical illness were not included in the model. However, we obtained children's and parents' reports of the children's psychopathology, clinicians' ratings of the children's impairment, and measures of family dysfunction. Another limitation was that the diagnoses and GAF scores were determined by a heterogeneous group of clinicians who were not specifically trained for the study reported here. Although administering a structured diagnostic instrument and a standardized measure of child functioning is challenging in a generalist, nonresearch setting, future studies would benefit from the addition of such measures. Their inclusion would contribute to the uniformity and reproducibility of results and remove potential clinician bias. Finally, in many areas summary scales such as the Family Assessment Device General Functioning Scale were used rather than more detailed instruments. Future research must identify particular aspects of family dysfunction, psychosocial impairment, and level of impairment that are associated with the choice of treatment setting.

Our study provided some evidence that experienced clinicians who base their decisions on referral information and initial assessments appropriately direct patients to alternative treatment settings and that they use an algorithm involving the severity of psychopathology and the presence of several vulnerability factors. Second, specific programs, such as a day treatment program for children with disruptive behavior disorders or a child and adolescent eating disorders program, provide care for individuals who have significantly more psychopathology and psychosocial impairment than individuals who are cared for in outpatient settings.

These findings have implications for treatment. To facilitate the movement of patients from inpatient and day treatment settings to less expensive and restrictive settings, treatment planning should target not only the presenting symptoms but other factors as well. A systemically informed intervention that addresses family dysfunction, parental mental health, and the effects of adverse family life events can help ensure that individuals are cared for and maintained in less restrictive, less costly settings.

Dr. McDermott is professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Western Australia in Perth, Australia. Ms. Roberts is a research officer in the Western Australian Department of Health in Perth. Dr. McKelvey, who was formerly professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Western Australia, is now professor and director of the division of child and adolescent psychiatry at Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland. Dr. Davies is adjunct lecturer in the departments of pediatrics and psychiatry and behavioral science at the University of Western Australia. Send correspondence to Dr. McDermott at the Princess Margaret Hospital for Children, Department of Paediatrics, GPO Box D184, Perth, WA 6001, Australia (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Mean scores on the Child Behavior Checklist of children assigned to one of three treatment settings or seen for psychiatric consultation only

|

Table 2. Mean competency scores on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) or the Youth Self-Report (YSR) of children assigned to one of three treatment settings or seen for psychiatric consultation only

|

Table 3. Mean scores on the Youth Self-Report of patients assigned to one of three treatment settings or seen for psychiatric consultation only

1. Goldman HH, Sharfstein SS: Are specialized psychiatric services worth the higher cost? American Journal of Psychiatry 144:626-628, 1987Google Scholar

2. Hersov L: Inpatient and day-hospital units, in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 3rd ed. Edited by Rutter M, Taylor E, Hersov L. London, Blackwell, 1994Google Scholar

3. Institute of Medicine: Research on Children and Adolescents With Mental, Behavioral, and Developmental Disorders. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1989Google Scholar

4. Children's Mental Health: Problems and Services: A Background Paper. Washington, DC, Office of Technology Assessment, 1986Google Scholar

5. Sharfstein SS: Quality improvement. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1767-1768, 1993Link, Google Scholar

6. Firth MT: An evaluation of the effectiveness of psychiatric treatment on adolescent in-patients and out-patients. Acta Paedopsychiatrica 55:127-133, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

7. Zimet SG, Farley GK, Zimet GD: Home behaviors of children in three treatment settings: an outpatient clinic, a day hospital, and an inpatient hospital. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33:56-59, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Therrien RW, Fischer J: Differences in the severity of disturbance of behaviors in children receiving inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment. Journal of Personality Assessment 43:276-280, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Archer RP, Stolberg AL, Gordon RA, et al: Parent and child MMPI responses: characteristics among families with adolescents in inpatient and outpatient settings. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 14:181-190, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Pfeffer CR, Plutchik R, Mizruchi MS: A comparison of psychopathology in child psychiatric inpatients, outpatients, and nonpatients: implications for treatment planning. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 174:529-535, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Goldberg DP: The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire: A Technique for the Identification and Assessment of Nonpsychotic Psychiatric Illness. London, Oxford University Press, 1972Google Scholar

12. Goldberg DP: Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, England, NFER Publishing, 1979Google Scholar

13. Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS: The McMaster Family Assessment Device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 9:171-180, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Halvorsen JG: Self-report family assessment instruments: an evaluative review. Family Practice Research Journal 11:21-55, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

15. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

16. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Youth Self Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

17. Achenbach TM: Epidemiological applications of multiaxial empirically based assessment and taxonomy, in The Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. Edited by Verhulst FC, Koot HM. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

18. Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Garton A, et al: Western Australian Child Health Survey: Developing Health and Well-Being in the Nineties. Perth, Western Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Institute for Child Health Research, 1995Google Scholar

19. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale, in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

20. Bird HR, Gould MS, Rubio-Stipec M, et al: Screening for childhood psychopathology in the community using the Child Behavior Checklist. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 30:116-123, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Cohen DJ: Psychosocial therapies for children and adolescents: overview and future directions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 23:141-156, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar