A Model for Predicting Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to develop a model for identifying patients with a high risk of developing alcohol withdrawal delirium after assessment in the emergency department. METHODS: Patients seeking acute treatment for alcohol withdrawal at St. Göran's hospital in Stockholm were evaluated for known risk factors for alcohol withdrawal delirium. All patients with any risk factor were admitted to the hospital and received standard treatment with benzodiazepines. All patients were evaluated at admission by the physician in charge at the psychiatric and dependency emergency unit at the hospital. Treatment and final assessment were conducted at the unit's inpatient acute-treatment facility. Correlations were determined between risk factors noted at admission and development of alcohol withdrawal delirium, as defined in DSM-IV, after admission. A total of 334 alcohol-dependent patients were included in the study. RESULTS: Twenty-three patients, or 6.9 percent, developed alcohol withdrawal delirium after admission despite benzodiazepine treatment. In a stepwise multiple regression model, five risk factors were significantly correlated with the development of alcohol withdrawal delirium: current infectious disease; tachycardia, defined as a heart rate above 120 beats per minute at admission; signs of alcohol withdrawal accompanied by an alcohol concentration of more than 1 gram per liter of body fluid; a history of epileptic seizures; and a history of delirious episodes. No patient without these five risk factors developed delirium. Conclusion: Assessment for five easily detectable risk factors can enable the clinician to make an accurate and quantitative assessment of a patient's risk of developing alcohol withdrawal delirium.

Alcohol withdrawal delirium, or delirium tremens, is a severe complication of alcohol dependency. Although rare, it must be identified because it is accompanied by substantial mortality, especially when complicated by secondary diseases (1,2,3). A decrease in mortality in recent decades has been attributed to the systematic use of benzodiazepines in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal (3,4). However, many patients who experience alcohol withdrawal delirium experience significant cognitive defects (5). In addition, once established, delirium tremens is difficult to treat (6). Therefore it is critical that patients with a high risk of alcohol withdrawal delirium be identified so that delirium can be prevented through prompt treatment, preferably with benzodiazepines (7,8).

Several investigators have evaluated various clinical features and patient history characteristics that predispose individuals to alcohol withdrawal delirium. Several authors have found that severe dependency—for example, prolonged drinking (3,4) and having high blood alcohol concentrations when signs of withdrawal occur (9)—predisposes a person to delirium. In addition, a drinking pattern that includes episodes of extremely high alcohol consumption was found to be important (10).

Several authors have pointed to abrupt cessation of intensive drinking as an important risk factor (3,6). Others found factors consistent with the development of kindling processes, described by Ballenger and Post (11), to be important. For example, previous episodes of alcohol withdrawal delirium or withdrawal-associated seizures were identified as important predictors of delirium (4,10,12,13). In addition, experience of a recent epileptic seizure was found to herald the development of alcohol withdrawal delirium (2,13). Alcohol withdrawal delirium is also related to the severity of overactivity of the autonomic nervous system, such as tachycardia and tremor (13,14). It is known that concurrent medical problems (1,10), including neurologic conditions such as ataxia and nonmedical use of sedative-hypnotic medication (10), increase the risk of alcohol withdrawal delirium.

However, most studies have not evaluated the relative importance and predictive capacity of various risk factors in the clinical prediction of alcohol withdrawal delirium. In addition, it is not always obvious in published reports whether the patients with delirium had the condition before admission or after treatment of withdrawal was instituted. In deciding on the nature and intensity of treatment, it is important to evaluate whether a patient who has not yet developed alcohol withdrawal delirium has a high risk of doing so.

This study aimed to explore the predictive capacity of known and acute assessable risk factors for alcohol withdrawal delirium in order to develop an accurate risk-prediction model for use with alcohol-dependent patients seeking acute treatment for alcohol withdrawal.

Methods

During a 16-month period (January 1997 to April 1998), all patients who sought treatment for alcohol withdrawal at the psychiatric and dependency emergency unit of St. Göran's Hospital in Stockholm were assessed with a standard protocol by the physician in charge for the presence of risk factors for severe alcohol withdrawal. The psychiatric and dependency emergency unit is responsible for all emergency treatment of alcohol- and drug-dependency disorders in the central-western part of Stockholm, a region with a population of approximately 310,000.

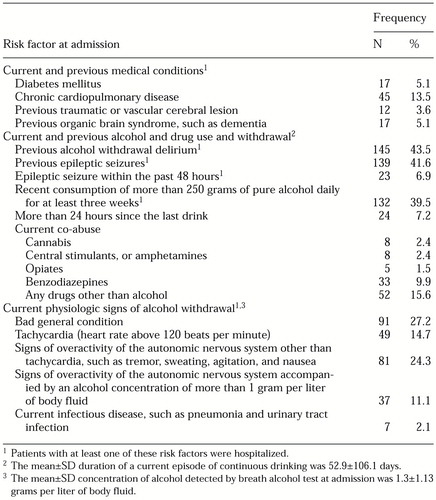

The risk factors we assessed were divided into three categories, as shown in Table 1—relevant current and previous medical conditions, current and previous alcohol and drug use and withdrawal, and current physiologic signs of alcohol withdrawal. For the purposes of the study, all risk factors were recorded as being either present or absent. All patients with at least one risk factor were admitted for inpatient treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Of those, all patients who did not already have ongoing delirium or other ongoing psychotic disturbances at the time of admission were included in the analysis. Patients who were readmitted for treatment of alcohol withdrawal during the study period were included in the analysis at their first admission only.

The diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal delirium was made if a patient developed a delirious state, as described in DSM-IV, during alcohol withdrawal. Standard treatment was given, which consisted of a fixed schedule of oxazepam in combination with administration of diazepam in response to symptoms. When signs of alcohol withdrawal occurred, 25 or 50 mg of oxazepam was given orally four times daily, together with 10 to 40 mg of diazepam every hour for as long as signs of withdrawal were present (7,15). After the signs of withdrawal had been under control for a period of 12 to 24 hours, the total benzodiazepine dosage was reduced by about 25 percent daily.

Multiple regression was used to evaluate the importance of each risk factor. Occurrence of alcohol withdrawal delirium was used as a dummy dependent variable. A value of 0 indicated that delirium did not develop after admission, and a value of 1 indicated that delirium did develop. The risk factors listed in Table 1 were used as independent variables. Dichotomous variables were entered as dummy variables. For each dummy variable, the regression coefficient expresses the expected probability that a risk factor is predictive of that variable (16). Independent variables were introduced into the model in a stepwise forward regression procedure, as long as the partial correlation of the next variable to be introduced was statistically significant (p<.05). The software package Statgraphics Plus (version 7.0; Manugistics, Inc., Rockville, Maryland) was used for all statistical computations.

Results

A total of 334 patients—251 men and 83 women—were included in the analysis. The mean duration of a current episode of continuous drinking was 53 days. A large proportion of patients—43.4 percent—had previously experienced alcohol withdrawal delirium, and 39.5 percent of the patients had an extremely high consumption of alcohol—that is, more than 18 standard drinks daily for at least three weeks, as shown in Table 1. Twenty-three patients, or 6.9 percent, developed alcohol withdrawal delirium after admission despite treatment with benzodiazepines.

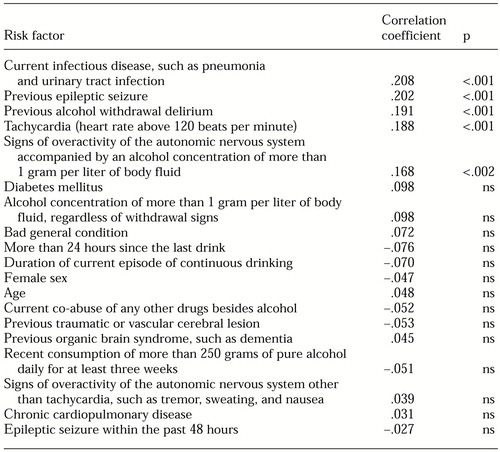

In a simple correlation analysis, five risk factors were significantly correlated with the development of alcohol withdrawal delirium after admission, as shown in Table 2. Two risk factors showed a trend toward correlation—the presence of diabetes mellitus and an alcohol concentration of more than 1 gram per liter of body fluid at admission; however, these associations were not significant.

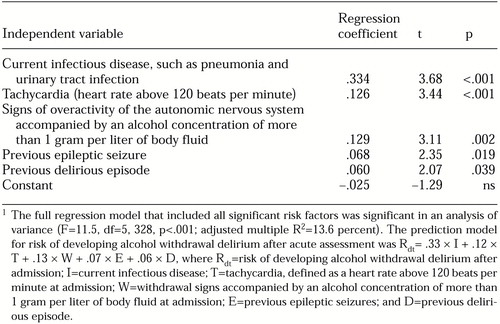

In the stepwise multiple regression analysis, the significantly correlated factors did not account for as much of the variation as in the simple regressions. The regression model showed a significant contribution of five risk factors to the development of alcohol withdrawal delirium after admission, as indicated in Table 3. The factors for which a trend toward correlation with the development of delirium was found were not significant predictors in the multiple regression. A history of alcohol withdrawal delirium and of epileptic seizures independently contributed only 6 percent and 6.8 percent, respectively, to the risk of developing delirium, despite their high correlations in the single regression analysis.

Because all significant independent variables as well as the dependent variable were dichotomous dummy variables, the regression coefficients in Table 3 indicate the independent relative risk of developing alcohol withdrawal delirium when the risk factor is present. Of the 334 patients, 112 had no significant risk factors, and none of these patients developed delirium.

Discussion

The final regression model allowed a quantified risk analysis of patients who sought acute care for alcohol withdrawal. The risk of developing delirium despite the prescribed treatment regimen increased as the value of the regression coefficient increased—for example, the presence of infectious disease increased the risk by 33.4 percent, severe tachycardia by 12.6 percent, and overactivity of the autonomic nervous system while the patient was still intoxicated by 13 percent (Table 3). Patients who had none of the significant risk factors did not develop delirium when they were treated with the regimen described. Thus we can conclude that a simple assessment at admission can be used to identify which patients need special attention and which patients need only standard treatment.

The study also showed that physical signs are the most important factor in predicting the development of alcohol withdrawal delirium. The finding that acute infections have a high correlation with delirium is consistent with established knowledge about precipitating factors for delirium in other organic syndromes, such as dementia (17,18). Phenomena that indicate overactivity of the autonomic nervous system, such as tachycardia, sweating, tremor, and nausea, even though they had a lower correlation than infection in our study, deserve close clinical attention, because they are more frequent in this population. In our study, 77 patients—23.1 percent of the total sample—had either severe tachycardia or other signs of overactivity of the autonomic nervous system while still intoxicated. Twelve of them, or 15.6 percent, developed alcohol withdrawal delirium.

As in several other studies, a correlation was observed between the development of alcohol withdrawal delirium and previous experience of delirium or epileptic seizure (13). However, the multiple regression model showed that the practical importance of this correlation is small. Interestingly, many of the risk factors that have previously been pointed out as being of interest—such as extreme drinking, long periods of continuous drinking, and benzodiazepine abuse —were found to be of no significance. This finding probably indicates that these factors do not act independently to increase risk. Also, it is possible that self-reports of current drinking intensity are of limited importance when collected in the emergency department from patients who are either intoxicated or in a state of withdrawal.

Conclusion

Five factors that are easily detectable in the emergency room—presence of infectious disease, tachycardia at admission, withdrawal signs accompanied by an alcohol concentration of more than 1 gram per liter of body fluid, a history of epileptic seizures, and a history of delirious episodes—can accurately predict outcome for patients seeking acute treatment for alcohol withdrawal.

Dr. Palmstierna is senior psychiatrist and psychiatric researcher in the department of clinical neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute's Centre for Dependency Disorders (Beroendecentrum Nord) at St. Göran's Hospital, Plan 12, P.O. Box 125 60, SE-112 81, Stockholm, Sweden (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Risk factors for development of alcohol withdrawal delirium and their prevalence among 334 patients hospitalized for treatment of alcohol withdrawal

|

Table 2. Simple correlation between development of alcohol withdrawal delirium after admission and various risk factors among 334 patients

|

Table 3. Risk factors significantly associated with development of alcohol withdrawal delirium among 334 patients, by stepwise multiple regression11

The full regression model that included all significant risk factors was significant in an analysis of variance (F=115, df=5, 328, p<.001; adjusted multiple R2=13.6 percent). The prediction model for risk of developing alcohol withdrawal delirium after acute assessment was Rdt= .33 × I + .12 × T + .13 × W + .07 × E + .06 × D, where Rdt=risk of developing alcohol withdrawal delirium after admission; I=current infectious disease; T=tachycardia, defined as a heart rate above 120 beats per minute at admission; W=withdrawal signs accompanied by an alcohol concentration of more than 1 gram per liter of body fluid at admission; E=previous epileptic seizures; and D=previous delirious episode.

1. Horstmann E, Conrad E, Daweke H: Severe course of delirium tremens: results of treatment and late prognosis [in German]. Medizinische Klinik 84:569-573, 1989Google Scholar

2. Gruner J, Voigt W: Morbidity rates in delirium tremens [in German]. Psychiatrie, Neurologie, und Medizinische Psychologie 36:331-339, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

3. Griffin RE, Gross GA, Teitelbaum HS: Delirium tremens: a review. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 93:929- 932, 1993Google Scholar

4. Cushman P: Delirium tremens: update on an old disorder. Postgraduate Medicine 82:117-122, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Dittmar G: Alcohol delirium: pathogenesis and therapy [in German]. Medizinische Klinik 86:607-612, 1991Google Scholar

6. Guthrie SK: The treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Pharmacotherapy 9:31-43, 1989Google Scholar

7. Adinoff B, Bone GHA, Linnoila M: Acute ethanol poisoning and the ethanol withdrawal syndrome. Medical Toxicology 3:172-196, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Saitz R, Mayo-Smith MF, Roberts MS, et al: Individualized treatment for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized double blind controlled trial. JAMA 17:519-523, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Kramp P, Hemmingsen R: Delirium tremens: some clinical features: part I. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 60:393-404, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Reich T, et al: The histories of withdrawal convulsions and delirium tremens in 1,648 alcohol dependent subjects. Addiction 90:1335-1347, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Ballenger JC, Post RM: Kindling as a model for alcohol withdrawal syndromes. British Journal of Psychiatry 133:1-14, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lechtenberg R, Worner TM: Total ethanol consumption as a seizure risk factor in alcoholics. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 85:90-94, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Salum I: Delirium Tremens and Certain Other Acute Sequelae of Alcohol Abuse [in Swedish]. Academic dissertation. Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, 1972Google Scholar

14. Makanjuola JD, Faragher B, Rees DW: Measurement of alcohol withdrawal in detoxification centre patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 140:523-525, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Saitz R, O'Malley SS: Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse: withdrawal and treatment. Medical Clinics of North America 81:881-907, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wonnacott RJ, Wonnacott TH: Introductory Statistics, 4th ed. New York, Wiley, 1985Google Scholar

17. Espino DV, Jules-Bradley AC, Johnston CL, et al: Diagnostic approach to the confused elderly patient. American Family Physician 57:1358-1366, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

18. Patterson C, Clair JK: Acute decompensation in dementia: recognition and management. Geriatrics 44:20-26, 1989Medline, Google Scholar