Moving Assertive Community Treatment Into Standard Practice

Abstract

This article describes the assertive community treatment model of comprehensive community-based psychiatric care for persons with severe mental illness and discusses issues pertaining to implementation of the model. The assertive community treatment model has been the subject of more than 25 randomized controlled trials. Research has shown that this type of program is effective in reducing hospitalization, is no more expensive than traditional care, and is more satisfactory to consumers and their families than standard care. Despite evidence of the efficacy of assertive community treatment, it is not uniformly available to the individuals who might benefit from it.

There is mounting interest among mental health care professionals in making mental health practices with demonstrated efficacy and effectiveness available in routine care settings (1,2). One such practice is assertive community treatment, a comprehensive community-based model for delivering treatment, support, and rehabilitation services to individuals with severe mental illness. Assertive community treatment is sometimes referred to as training in community living, the Program for Assertive Community Treatment (PACT), continuous treatment teams, and, within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), intensive psychiatric community care.

Assertive community treatment is appropriate for individuals who experience the most intractable symptoms of severe mental illness and the greatest level of functional impairment. These individuals are often heavy users of inpatient psychiatric services, and they frequently have the poorest quality of life.

Research has shown that assertive community treatment is no more expensive than other types of community-based care and that it is more satisfactory to consumers and their families (3). Reviews of the research consistently conclude that compared with other treatments under controlled conditions, such as brokered case management or clinical case management, assertive community treatment results in a greater reduction in psychiatric hospitalization and a higher level of housing stability. The effects of assertive community treatment on quality of life, symptoms, and social functioning are similar to those produced by these other treatments (3,4,5,6,7,8). Other studies have found associations between assertive community treatment and a lower level of substance use among individuals with dual diagnoses (9,10).

Cost analyses have shown that assertive community treatment is cost-effective for patients with extensive prior hospital use (11,12,13,14,15,16), and in the long run it may provide a more cost-effective alternative to standard case management for individuals with co-occurring substance use disorders (17). Consumer satisfaction has been less thoroughly investigated; however, the majority of existing studies found that consumers and their families were more satisfied with assertive community treatment than with other types of intervention (3,5).

The evidence base for assertive community treatment is not without its limitations. For example, its effectiveness as a jail diversion program has not been clearly established, despite increasing interest in its use for this purpose (6). There is also widespread speculation that it may be less effective than more conventional treatments for individuals with personality disorders, although little hard evidence exists to either support or refute this idea (18). Also, its effectiveness for individuals from different ethnic groups has not been empirically established. Despite these limitations, assertive community treatment has many proven benefits, as noted above.

In many cases, assertive community treatment is not available to individuals who might benefit from this type of intervention (19). The purpose of this article is to familiarize mental health care providers with the principles of the assertive community treatment model and issues pertaining to its implementation. The article is a prelude to the detailed guidelines and strategies that are being developed as an implementation "toolkit" in the Evidence-Based Practices Project, an initiative funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Principles of assertive community treatment

The practice of assertive community treatment originated almost 30 years ago when a group of mental health professionals at the Mendota Mental Health Institute in Wisconsin realized that many individuals with a severe mental illness were being discharged from inpatient care in stable condition, only to return after a relatively short time. Rather than accept the inevitability of repeated hospitalizations, these professionals looked at how mental health services were being delivered and tried to determine what could be done to help persons with mental illness live more stable lives in the community (20,21,22,23).

They designed a service delivery model in which a team of professionals assumes direct responsibility for providing the specific mix of services needed by a consumer, for as long as they are needed. The team ensures that services are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Rather than teaching skills or providing services in clinical settings and expecting them to be generalized to "real-life" situations, services are provided in vivo—that is, in the settings and context in which problems arise and support or skills are needed.

Team members collaborate to integrate the various interventions, and each consumer's response is carefully monitored so that interventions can be adjusted quickly to meet changing needs. Services are not limited to a predetermined set of interventions—they include any that are needed to support the consumer's optimal integration into the community (24). Rather than brokering services, the team itself is the service delivery vehicle in the model. Table 1 lists services provided by team members (25).

An assertive community treatment team consists of about ten to 12 staff members from the fields of psychiatry, nursing, and social work and professionals with other types of expertise, such as substance abuse treatment and vocational rehabilitation. Although the number of members may vary, the operating principle of the team is that it must be large enough to include representatives from the required disciplines and to provide coverage seven days a week, yet small enough so that each member is familiar with all the consumers served by the team. A staff-to-consumer ratio of one to ten is recommended, although teams that serve populations that have particularly intensive needs may find that a lower ratio is necessary initially. As the consumer population stabilizes, a higher ratio can be tolerated. A lower ratio may be appropriate in rural areas where considerable distances must be covered (22).

Team members are cross-trained in each other's areas of expertise to the maximum extent feasible, and they are readily available to assist and consult with each other. This team approach is facilitated by a daily review of each consumer's status and joint planning of the team members' daily activities (26).

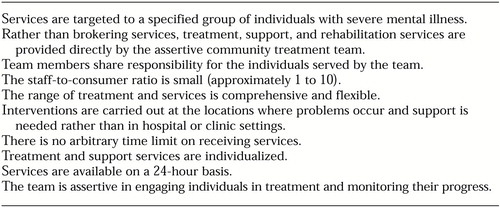

Although this model of assertive community treatment has been enhanced and modified to meet local needs or target specific clinical populations, its basic principles, which are summarized in Table 2, remain constant.

Variations on a theme

Assertive community treatment programs—with adaptations and enhancements—have been implemented in 35 states and in Canada, England, Sweden, and Australia (3,6,27). Programs operate in both urban and rural settings (8,27,28,29,30,31,32). Some emphasize outreach to homeless persons (33,34) or target veterans with severe mental illness (15,16,35). Others focus on co-occurring substance use disorders (10,17,36) or employment (21,37). Programs also differ in the extent to which they focus on personal growth or on basic survival (38). Some include consumers and family members as active members of the treatment teams (29,34).

Some program planners have questioned whether certain structural characteristics of assertive community treatment, such as the lack of a time limit on services, the team approach, and the provision of 24-hour crisis services, are overly expensive (39), and mental health authorities in some states have modified the model in terms of scope, eligibility, and programmatic features (6).

At the same time, several national organizations have promulgated standards to promote consistency among assertive community treatment programs. These standards differ from organization to organization. For instance, the standards developed by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (26) specify that programs be directly responsible for providing services to consumers 24 hours a day and for an unlimited time.

The standards promulgated by the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (40) allow for teams to arrange crisis coverage through other crisis intervention services. A recent directive from the VA (41) specifies that veterans may be shifted to less intensive care if explicit criteria for readiness are met after one year of assertive community treatment. Recommendations for staff-to-consumer ratios also vary among the different sets of standards.

The structural and operational elements addressed in the standards have potential fiscal consequences (6). For instance, it may be less costly for mental health systems to shift individuals to less intensive services than to provide assertive community treatment for a lifetime. Also, staffing an assertive community treatment team to provide 24-hour coverage rather than having consumers use existing crisis services on evenings and weekends will affect costs, as will variations in staff-to-consumer ratios.

Mental health systems will no doubt feel pressure to structure their programs in ways that minimize costs. However, current research does not provide detailed guidance for many of the decisions that program planners must make about the specifics of program structure. Program planners will want to keep in mind that the cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment within a particular mental health system will depend not only on how the program is structured but also on the characteristics of the individuals targeted to receive treatment and the overall availability of mental health services in the community where a team operates.

There is some evidence that assertive community treatment is most cost-effective for individuals who have a history of high service use (15). Because hospital-based care is more expensive than community-based care, systems that target these individuals may realize greater cost savings. In communities where access to mental health services is limited, an assertive community treatment program may result in better access and, consequently, more effective treatment, but with higher service use and associated costs (8).

Critical program components

Given the variations among assertive community treatment programs in research studies and in actual practice, it would be helpful to program planners to know which core components are critical for effectiveness and which can be altered to fit local needs without affecting outcomes. Some specific program elements, such as a substance abuse treatment component and a supported employment component, have been linked to some specific favorable outcomes (9,37).

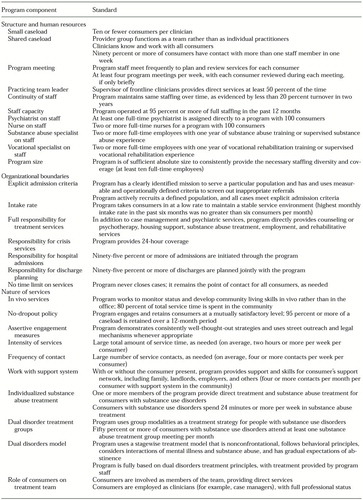

Most research, however, has focused on an aggregate of program elements, such as those described in the Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Fidelity Scale (DACTS) (42). The DACTS components, which are listed in Table 3, were compiled on the basis of an examination of the literature, expert consensus, and previous research on critical components of assertive community treatment (42,43,44). Some components codify basic characteristics of good clinical practice—for example, continuity of staff—rather than principles that differentiate assertive community treatment from other models—for example, in vivo services (Schaedle R, McGrew JH, Bond GR, unpublished data, 2000).

The results of research on assertive community treatment indicate that programs that adhere overall to the DACTS components are more effective than programs with lower adherence in reducing hospital use (42), reducing costs (11), improving substance abuse outcomes for individuals with dual diagnoses (45,46), and improving functioning and consumers' quality of life (31,45). It should be noted that these studies compared assertive community treatment with standard care at the program level; the various specific structural components of assertive community treatment have not been systematically varied to determine their relative effects on outcomes.

The Lewin Group, a health services research firm under contract with the Health Care Finance Administration and SAMHSA, attempted to discern which of the various principles, structural elements, and organizational factors described in assertive community treatment standards and fidelity measures are most essential for successful outcomes (6). According to descriptions of programs in the literature, the characteristics most commonly reported in studies in which assertive community treatment produced better results than alternative treatments were found to be a team approach, in vivo services, assertive engagement, a small caseload, and explicit admission criteria. Although these findings suggest the importance of including these components in an assertive community treatment program, it should be noted that the study included only programs that adhered closely to the model and thus did not have the variability needed to determine the differential effects of any specific component on outcomes.

Other issues related to implementation

To our knowledge, no model for implementing an assertive community treatment program has been empirically tested. However, the principles and approaches found in research on changing health care practices should apply to this type of program. This research shows that, in general, successful implementation of new practices requires a leadership capable of initiating innovation, adequate financing, administrative rules and regulations that support the new practice, practitioners who have the skills necessary to carry out the new practice, and a means of providing feedback on the practice (2).

Because there has been no research specifically on methods for implementing assertive community treatment programs, the sources for the following discussion are observations of factors that hindered faithful replication of the assertive community treatment model in research studies; published manuals on implementing assertive community treatment, with contributions by the model's originators (22,26); telephone interviews with individuals experienced in implementing these types of programs; experiences in disseminating assertive community treatment programs within the VA; focus groups conducted by the Lewin Group with state mental health and Medicaid administrators; and numerous focus groups of consumers who have participated in assertive community treatment programs.

Implementation issues and strategies are presented for four key groups—mental health service system administrators, assertive community treatment program directors and team members (discussed together), and consumers.

Issues for mental health system administrators

Mental health system administrators are critical to the successful implementation of assertive community treatment programs. They provide the vision, set the goals, and ensure the instrumental support needed for the adoption of the model in routine practice. In this section, we address three issues that confront mental health system administrators: funding, ensuring adherence to the model, and planning the implementation of multiple programs.

Funding. Historically, funding for mental health services has been devoted primarily to the support of hospital-based and office-based care. One challenge in implementing assertive community treatment is that traditional funding streams may not cover the breadth of services provided for under the model. The primary source of funding for assertive community treatment is typically reimbursement through Medicaid under the rehabilitative services or targeted case management categories. In the VA, funding has been provided through special regional and national initiatives (47,48).

Reimbursement under Medicaid, when limited to the parameters of the rehabilitative services or targeted case management categories, does not always cover all the services provided by an assertive community treatment team, such as failed attempts to contact an individual. Some states have augmented Medicaid funding by blending Medicaid reimbursement with funds from other sources, such as revenues for substance abuse treatment or housing. Because each funding stream has separate requirements that are often contradictory, blended funding can be cumbersome; however, it does offer a potential solution to the limitations of Medicaid funding (6).

New Hampshire and Rhode Island have addressed the limitations of Medicaid by revising their state plans to cover the services provided by assertive community treatment teams. States may find that consultation with a Medicaid expert is helpful in developing financial constructs to cover assertive community treatment services.

Ensuring adherence to the model. It is not uncommon for health care programs to depart from the model they seek to replicate. Variations may be intentional, such as those introduced in response to local conditions (6,38). Variations may also occur when shortages of resources place pressure on administrators to make trade-offs between program effectiveness and program costs. Finally, unintended variations may occur, such as when the model is not clearly understood, when the training provided is inadequate, or when staff members regress to previous, more familiar practices (38).

A number of safeguards can be instituted by system administrators to prevent unintended variations. First, mental health systems can include standards for assertive community treatment programs in state plans (22,49,50). However, a survey of states that have assertive community treatment initiatives found that the standards enacted by individual states often failed to address many elements included in the DACTS or they lacked specificity (50). Since the survey was conducted, SAMHSA has supported the development of national standards for assertive community treatment programs that can serve as a model for state standards (26).

Implementing the multilevel changes needed to disseminate a program model such as assertive community treatment throughout a state system may take three to five years—a period that exceeds the tenure of most state mental health directors (49). A steering committee that is contractually mandated by the state mental health authority and that serves in an oversight capacity can help to ensure that initiatives are sustained as administrations change over time. Advisory groups with multiple stakeholders can play a similar role at the team or agency level. The advisory group can serve as a liaison between the community and the treatment team and other bodies within the provider agency. Such groups are currently used in programs in Tennessee, Montana, Florida, and Oklahoma.

Advisory groups should include individuals who are knowledgeable about severe mental illness and the challenges that people with mental illness face in living in the community; consumers of mental health services and their relatives; and community stakeholders who have an interest in the success of the assertive community treatment team, such as representatives of homeless services, the criminal justice system, consumer peer support organizations, and community colleges, as well as landlords and employers.

Well-delineated training, supervision, and consultation can help to ensure that the model is understood initially by the practitioners who will carry out the program; however, ongoing monitoring of program fidelity is also important for continued efficiency and effectiveness (47,48,50). The DACTS can be used either by persons within the mental health system or by external experts to measure a program's adherence to the model (42). This instrument is useful for ensuring appropriate initial implementation as well as maintenance of fidelity over time (47,48,51).

Multiple programs. Experience suggests that states implementing multiple programs will want to consider the pace at which new teams are started (38). Some states, such as New Jersey and Pennsylvania, have successfully launched multiple programs simultaneously. The concurrent development of teams allows for shared training, which can increase the connections between newly forming teams, enhance practitioners' understanding of the model, help counteract the isolation of individual teams, and encourage mutual problem solving (38). On the other hand, implementing teams sequentially allows systems to use teams that were trained early in the implementation effort to mentor and monitor subsequent teams. The VA has used this approach to implement 50 teams over the past decade (47,51).

Another strategy to facilitate the implementation of multiple programs is to appoint a clinical coordinator who is experienced in assertive community treatment and who has frequent, ongoing contact with each new program to assist with and assess implementation. This individual provides ongoing formal and informal training and plays an important role in the early detection of potential problems (52).

Issues for program directors and team members

There is evidence in the literature—and unanimity among the experts we interviewed—that successful replication of assertive community treatment programs is facilitated when program directors have a clear concept of the model's goals and treatment principles (42). Program directors who are committed to the model are better able to hold the staff accountable for fidelity to the model and to provide the leadership and instrumental support needed to ensure its successful adoption by staff. Visits by program directors and team members to existing programs with proven fidelity and ongoing mentoring by someone experienced with the model are highly recommended (22,31).

Policies and procedures. Existing agency policies may not cover all activities of an assertive community treatment team. For example, team members routinely transport individuals, an activity that may not be addressed in the policy and procedures of office-based programs. Some programs address this issue by reimbursing team members for the cost of insurance and operating expenses for their personal vehicles. Other programs elect to have team members use agency vehicles.

Another issue that requires forethought is how medication delivery will be accomplished. Team members, both medical and nonmedical, may at times deliver medications to individuals in the community. Because nonmedical personnel cannot dispense medications, some programs establish procedures whereby consumers set up their own medications in "organizers" so that nonmedical personnel can make deliveries.

Yet another issue that administrators and staff may be concerned about is the safety of team members when they are out in the community. Teams often find that cell phones provide reassurance and also facilitate nonemergency communication.

More detailed discussions of these issues can be found in other publications (22,26). Actual model policies are available in the PACT start-up manual (26).

Selecting and retaining team members. Methods for providing assertive community treatment may differ considerably from those that professional staff have been exposed to previously. For example, members of an assertive community treatment team work interdependently, and the majority of their time is spent in community settings. Pragmatism, street smarts, initiative, and the ability to work with a group are particularly desirable characteristics for team members (22). Competitive salaries are important in attracting and retaining competent individuals (6,26,38).

As noted, mental health consumers hold positions on some assertive community treatment teams (29,34). Personal experience with mental illness is thought to afford these individuals a unique perspective on the mental health system. At the same time, concerns have been expressed that consumers may be more vulnerable than others to the stress associated with providing mental health services and the difficulties of maintaining boundaries and that they may face stigmatization by other professionals (53,54). There are no data to suggest that consumers should be restricted from filling any position on a team for which they might be qualified. When consumers fill the role of peer specialist rather than other professional roles, their services may not be covered by third-party reimbursement (55), and programs will need to identify other revenues to fund these positions (6).

Training. Implementing assertive community treatment involves changing the type of work staff members may be used to as well as the manner in which they work. Working in community-based care also casts a different light on a staff member's cultural competency and professional boundaries.

Consultants who have been involved in implementing successful teams suggest that members of a new team shadow an experienced team, that they receive several full days of didactic training before program start-up, and that they take part in intermittent booster training sessions. This training sequence can be supplemented with videos, manuals, and workbooks, some of which are currently under development and will take the form of an implementation toolkit that will be tested in the field.

As newly forming teams encounter the pressures of a growing caseload, it is tempting to resort to the more traditional individual case management practice. Continuous on-site and telephone supervision is important in helping new teams maintain a shared-caseload approach (21,22,26,56,57,58,59,60).

Organizational integration of the team. The relationship between the assertive community treatment team and the larger system of care is also important. At one extreme, a team can be too detached from the larger system, either because it is physically isolated or because other programs view the team as specialized and the team's activities as unrelated to their own daily activities.

A degree of detachment can help to ensure that the team takes primary responsibility for providing a full range of services rather than relying on programs in the larger service delivery system. On the other hand, if a team is too detached, it may have difficulty developing channels of formal and informal communication with professionals in the larger service system. If the team is too autonomous or appears aloof, team members will find it difficult to successfully broker services for consumers when they are needed (31,59).

At the other extreme, problems can arise when a team cannot make independent decisions consistent with program principles because of expectations imposed on it by the larger organization. For instance, in a case in which assertive community treatment was attempted with individuals who had severe mental illness and mental retardation and who were living in a group home, the policies and practices of the mental retardation program were imposed on the assertive community treatment team. The team found it difficult to adhere to the practices of the mental retardation program and at the same time put the core principles of the assertive community treatment model into practice (61).

It is also sometimes difficult for assertive community treatment to emerge as an autonomous program, in part because other programs operating within a conceptual framework of compartmentalized service delivery may find it difficult to understand the assertive community treatment model (38). When teams lack autonomy, it is difficult to respond to consumers' changing needs in a manner consistent with the principles of the model (31,61).

Adequate channels of communication and respect for the autonomy of the team can be facilitated when other programs operating within the system and in the community have a clear idea of the goals and methods of the assertive community treatment program. Systemwide training in the principles of the model can help in this regard.

Issues for consumers

Studies have found that individuals who receive assertive community treatment report greater general satisfaction with their care than those who receive other services (5). However, some consumer groups strongly oppose the widespread dissemination of assertive community treatment. They believe that it is a mechanism for exerting social control over individuals who have a mental illness, particularly through the use of medications; that it can be coercive; that it is paternalistic; and that it may foster dependency (62,63,64).

A recent study of strategies used by assertive community treatment teams to pressure consumers to change behaviors or to stay in treatment shows that more coercive interventions, such as committing individuals to a hospital against their will, were used with less that 10 percent of consumers. More coercive interventions were used most often when consumers had recent substance abuse problems, a history of arrest, an extensive history of hospitalization, or more severe symptoms (65). An earlier study of consumers who were receiving assertive community treatment found that about one of every ten believed that the treatment was too intrusive or confining or that it fostered dependency (66).

It may not be possible to satisfy the concerns of consumer groups that object on principle to the assertive community treatment model, but it is important to acknowledge that this practice, like any other, has some potential to be used in a coercive manner. The issue of coercion may be of particular concern when this model is used in conjunction with outpatient commitment or in forensic settings, where staff must balance their clinical role with their legal responsibilities (6,55).

The idea that assertive community treatment is paternalistic may stem from the assumption that once individuals are deemed to be appropriate candidates for this service, they will require the same level of service for life. This assumption is called into question by studies suggesting that it is possible to transfer stabilized individuals to less intensive services with no adverse consequences (16,67,68).

Consumers' dissatisfaction with the treatments offered by the mental health system has a basis in their own experiences. Mental health providers can become more aware of consumers' concerns about assertive community treatment when consumers take an active part in state and local advisory groups and serve as team members. Also, research on consumers' perspectives on assertive community treatment, which has been limited largely to studies of consumer satisfaction, needs to be expanded (62).

Differing viewpoints about assertive community treatment—as well as about other forms of mental health treatment—are to be expected, and it is important that providers be aware of them. Furthermore, individuals who do not want to use assertive community treatment services should be able to select from alternative services along a continuum of care, even when such services do not have as strong an evidence base as assertive community treatment.

Conclusions

Since the inception of assertive community treatment nearly 30 years ago, research has repeatedly demonstrated that it reduces hospitalization, increases housing stability, and improves the quality of life for those individuals with severe mental illness who experience the most intractable symptoms and experience the greatest impairment as a result of mental illness. This model of delivering integrated, community-based treatment, support, and rehabilitation services has been adapted to a variety of settings, circumstances, and populations.

Although research shows that greater adherence to a group of core principles produces better outcomes, the relationship between specific structural aspects of assertive community treatment programs and outcomes is not always clear. When this model is being implemented, thoughtful consideration should be given to research on assertive community treatment programs and local conditions. Issues that should be considered include adequate funding, monitoring of fidelity, adaptation of policies and procedures to accommodate the model, and adequate training of professional staff. Tools that provide practical information on how to address issues related to implementing the assertive community treatment model will be available in the near future.

Acknowledgments

This article was written in conjunction with the Evidence-Based Practices Project sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. It is supported by grant 280-00-8049 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The authors thank Paul Gorman, M.Ed., and Gary R. Bond, Ph.D., for their comments and suggestions.

Ms. Phillips is a research associate and Dr. Burns is professor of medical psychology at Duke University Medical Center. Ms. Edgar is director of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill Technical Assistance Center for the Program for Assertive Community Treatment in Arlington, Virginia. Dr. Linkins is vice-president of the Lewin Group in Falls Church, Virginia. Dr. Rosenheck is director of the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare in West Haven and professor in the departments of psychiatry and public health at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven. Dr. Mueser and Dr. Drake are professors at Dartmouth Medical School and scientific director and director, respectively, of the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center. Dr. McDonel Herr is with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in Rockville, Maryland. Address correspondence to Ms. Phillips at Box 3454, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Services provided by assertive community treatment team members

|

Table 2. Ten principles of assertive community treatment

|

Table 3. Indicators of high fidelity in an assertive community treatment program

1. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, 1999Google Scholar

2. Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 52:45-55, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Burns BJ, Santos AB: Assertive community treatment: an update of randomized trials. Psychiatric Services 46:669-675, 1995Link, Google Scholar

4. Bedell JR, Cohen NL, Sullivan A: Case management: the current best practices and the next generation of innovation. Community Mental Health Journal 36:179-194, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: critical ingredients and impact on consumers. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 9:141-159, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Assertive Community Treatment Literature Review. Falls Church, Va, Lewin Group, 2000Google Scholar

7. Taube CA, Morlock L, Burns BJ, et al: New Directions in Research on Community Treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:642-647, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Mueser K, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37-74, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Drake RE, McHugo G, Clark R, et al: Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:201-213, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Teague GB, Drake RE, Ackerson T: Evaluating use of continuous treatment teams for persons with mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 46:689-695, 1995Link, Google Scholar

11. Latimer E: Economic impacts of assertive community treatment: a review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 44:443-454, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wolff LI, Barry KL, Dien GV, et al: Estimated societal costs of assertive community mental health care. Psychiatric Services 46:898-906, 1995Link, Google Scholar

13. Essock S, Frisman L, Kontos N: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment teams. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:179-190, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lehman A, Dixon L, Hoch J, et al: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:346-352, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Rosenheck RA, Neale M, Leaf P, et al: Multisite experimental cost study of intensive psychiatric community care. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:129-140, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rosenheck RA, Neale M: Intersite variation in the impact of intensive psychiatric community care on hospital use. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:191-200, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Clark RE, Teague GB, Ricketts SD, et al: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment versus standard case management for persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Health Services Research 33:1285-1308, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

18. Weisbrod BA: A guide to cost-benefit analysis, as seen through a controlled experiment in treating the mentally ill. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 7:808-847, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Survey co-investigators of the PORT project: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Marx AJ, Test MA, Stein LI: Extrahospital management of severe mental illness: feasibility and effects of social functioning. Archives of General Psychiatry 29:505-511, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Stein LI: Innovating Against the Current. Madison, Mental Health Research Center, University of Wisconsin, 1992Google Scholar

22. Stein LI, Santos AB: Assertive Community Treatment of Persons With Severe Mental Illness. New York, Norton, 1998Google Scholar

23. Test MA: Training in community living, in Handbook of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Edited by Liberman RP. New York, Macmillan, 1992Google Scholar

24. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:400-405, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Burns BJ, Swartz MS: Hospital Without Walls: Videotape Study Guide. Durham, NC, Division of Social and Community Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center, 1994Google Scholar

26. Allness DJ, Knoedler WH: The PACT Model of Community-Based Treatment for Persons With Severe and Persistent Mental Illnesses: A Manual for PACT Start-Up. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1999Google Scholar

27. Deci PA, Santos AB, Hiott DW, et al: Dissemination of assertive community treatment programs. Psychiatric Services 46:676-678, 1995Link, Google Scholar

28. Rapp C: The active ingredients of effective case management: a research synthesis. Community Mental Health Journal 34:363-380, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Dixon LB, Stewart B, Krauss N, et al: The participation of families of homeless persons with severe mental illness in an outreach intervention. Community Mental Health Journal 34:251-259, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Lehman A, Dixon L, Kernan E, et al: A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1038-1043, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. McDonel EC, Bond GR, Salyers M, et al: Implementing assertive community treatment programs in rural settings. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 25:153-173, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Santos AB, Deci PA, Dias JK, et al: Providing assertive community treatment for severely mentally ill patients in a rural area. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:34-39, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

33. Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF: Pathways to housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 51:487-505, 2000Link, Google Scholar

34. Morse GA, Caslyn RJ, Allen G, et al: Experimental comparison of the effects of three treatment programs for homeless mentally ill people. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:1005-1009, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

35. Rosenheck RA, Neale M: Cost-effectiveness of intensive psychiatric community care for high users of inpatient services. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:459-466,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Bond GR, McDonel EC, Miller LD, et al: Assertive community treatment and reference groups: an evaluation of their effectiveness for young adults with serious mental illness and substance abuse problems. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 15:31-43, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391-399, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Bond G: Variations in an assertive outreach model. New Directions for Mental Health Services 52:65-80, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. McGrew JH, Bond GR: The association between program characteristics and service delivery in assertive community treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 25:175-189, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Assertive community treatment, in CARF 2000 Behavioral Health Standards Manual. Tucson, Ariz, Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities, 2000Google Scholar

41. VHA Mental Health Intensive Case Management (MHICM): VHA Directive 2000-024. Washington, DC, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2000Google Scholar

42. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:216-232, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. McGrew J, Bond GR: Critical ingredients of assertive community treatment: judgments of the experts. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:113-125,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. McGrew JH, Bond GR, Dietzen L, et al: Measuring the fidelity of implementation of a mental health program model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:113-125, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

45. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Teague GB: Fidelity to assertive community treatment and consumer outcomes in the New Hampshire dual disorders study. Psychiatric Services 50:818-824, 1999Link, Google Scholar

46. Fekete DM, Bond GR, McDonel EC, et al: Rural intensive case management: a controlled study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:371-379, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

47. Rosenheck RA, Neale M, Baldino R, et al: Intensive Psychiatric Community Care: A New Approach to Care for Veterans With Serious Mental Illness in the Department of Veterans Affairs. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 1997Google Scholar

48. Rosenheck RA, Neale M: Development, implementation, and monitoring of intensive psychiatric community care in the Department of Veterans Affairs, in Achieving Quality in Psychiatric and Substance Abuse Practice: Concepts and Case Reports. Edited by Dickey B, Sederer L. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, in pressGoogle Scholar

49. Santos AB, Henggler SW, Burns BJ, et al: Research on field-based services: models for reform in the delivery of mental health care to populations with complex clinical problems. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1111-1123, 1995Link, Google Scholar

50. Meisler N: Assertive community treatment initiatives: results from a survey of selected state mental health authorities. Community Support Network News 11:3-5, 1997Google Scholar

51. Neale M, Rosenheck RA, Baldino R, et al: Intensive Psychiatric Community Care (IPCC), in the Department of Veterans Affairs Third National Performance Monitoring Report FY 1999. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2000Google Scholar

52. McGrew JH, Bond GR, Dietzen LL, et al: A multisite study of client outcomes in assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services 4:696-701, 1995Google Scholar

53. Paulson R, Herinckx H, Demmler J, et al: Comparing practice patterns of consumer and non-consumer mental health service providers. Community Mental Health Journal 35:251-269, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Felton CJ, Stastny P, Shern DL, et al: Consumers as peer specialists on intensive case management teams: impact on clients. Psychiatric Services 46:1037-1044, 1995Link, Google Scholar

55. Solomon P, Draine J: One-year outcomes of a randomized trial of case management with seriously mentally ill clients leaving jail. Evaluation Review 19:256-274, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

56. Rutkowski P, Plum T, McCarthy D, et al: P/ACT dissemination and implementation from three states and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Community Support Network News 11:8-9, 1997Google Scholar

57. Cook JA, Horton-O'Connell T, Fitzgibbon G, et al: Training for state-funded providers of assertive community treatment. New Directions in Mental Health Services, 79:55-64, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Hadley TR, Roland T, Vasko S, et al: Community treatment teams: an alternative to state hospital. Psychiatric Quarterly 68:77-90, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Stein LI, Test MA: Retraining hospital staff for work in a community program in Wisconsin. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 27:266-268, 1976Abstract, Google Scholar

60. Witheridge TF: The assertive community treatment worker: an emerging role and its implications for professional training. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:620-624, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

61. Meisler N, McKay CD, Gold PB, et al: Using principles of ACT to integrate community care for people with mental retardation and mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 6:77-83, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Spindel P, Nugent J: The Trouble With PACT: Questioning the Increasing Use of Assertive Community Treatment Teams in Community Mental Health. Consumer Organization and Networking Technical Assistance Center, Charleston, WV. Available at http://www.contac.org/nec.htmGoogle Scholar

63. Fischer DB, Ahern L: Personal Assistance in Community Existence (PACE): an alternative to PACT. Ethical Human Sciences and Services 2:87-92, 2000Google Scholar

64. Estroff S: Making It Crazy: An Ethnographic Study of Psychiatric Clients in an American Community. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1981Google Scholar

65. Neale M, Rosenheck RA: Therapeutic limit setting in an assertive community treatment program. Psychiatric Services 51:499-505, 2000Link, Google Scholar

66. McGrew JH, Wilson R, Bond GR: Client perspectives on critical ingredients of assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:13-21, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

67. Salyers MP, Masterton TW, Fekete DM, et al: Transferring clients from intensive case management: impact on client functioning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:233-245, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, et al: Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a "critical time" intervention after discharge from a shelter. American Journal of Public Health 87:256-262, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar